Quick, Abraham Lincoln buffs! Can you name all the dates Lincoln delivered a public address in Indiana after moving to Illinois in 1830?

Did you guess February 11 and 12, 1861? Identifying those days were probably fairly easy since that was when Lincoln journeyed through Indiana en route to Washington for his first inauguration. According to historical records, he delivered whistle-stop speeches at State Line City, Lafayette, Thorntown, Lebanon, and Zionsville. His train stopped at Indianapolis that evening where Governor Oliver P. Morton and 20,000 Lincoln supporters welcomed him. He addressed the citizens of Indiana from the train platform before he disembarked to his hotel room at the Bates House. Lincoln adherents called upon the president-elect later that evening, and he delivered an ad hoc speech from a balcony of the hotel. He resumed his journey east the next morning, which also happened to be his fifty-second birthday. Lincoln continued to greet and deliver short speeches to well-wishers in Shelbyville, Greensburg, Morris, and Lawrenceburg as his train steamed on to Cincinnati, Ohio.

If you are an advanced Lincoln enthusiast, you may be able to identify another Lincoln visit to Indiana that occurred in 1844 while he campaigned for Whig presidential candidate Henry Clay. During that fall visit, he spoke at the Spencer County Courthouse in Rockport.

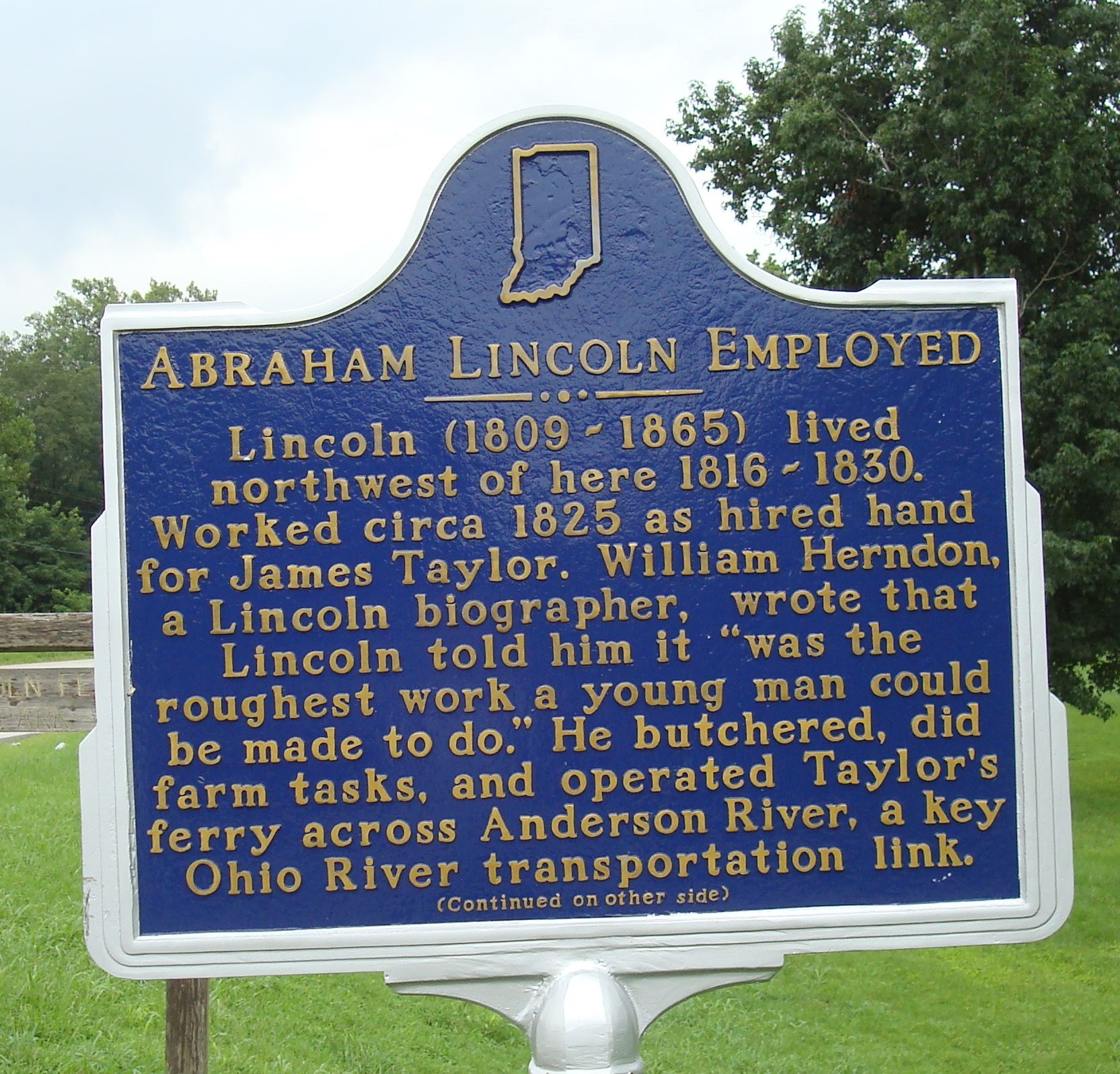

According to oral lore and tradition, he made several other speeches around Spencer County (and allegedly spoke in Knox, Daviess, Warrick, and Vanderburgh counties). However, the Rockport address is the only southern Indiana speech corroborated with a contemporary source. While in Spencer County, Lincoln visited his boyhood home and the graves of his mother and sister. This would be Lincoln’s first and only return to his childhood home since he left Indiana in 1830.

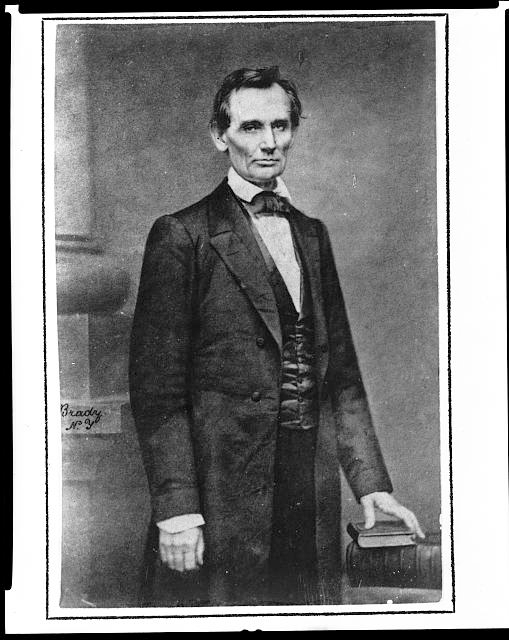

Aside from those two visits in 1844 and 1861, most Lincoln fans would be hard-pressed to identify the other time that Lincoln visited Indiana for political purposes. It happened on September 19, 1859 in Indianapolis, where he delivered a speech so obscure that it was largely forgotten for 70 years before a Lincoln researcher and an Indiana State Library employee uncovered it in an issue of a short-lived Indianapolis newspaper, the Daily Evening Atlas.

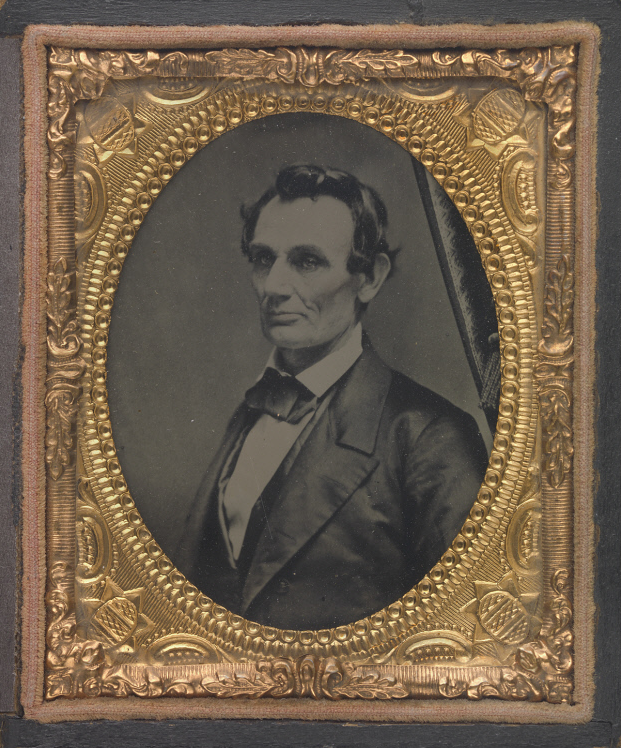

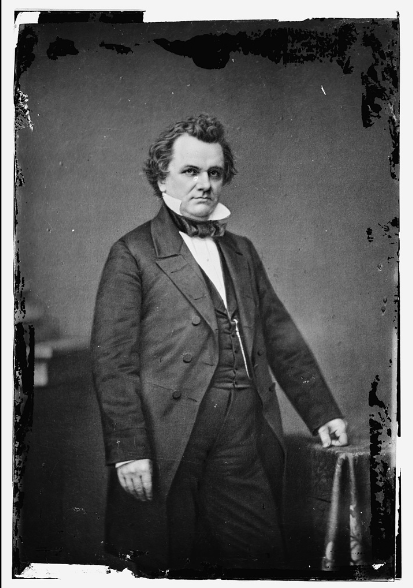

First, some historical context is helpful to illuminate Lincoln’s Indianapolis speech. In January 1859, Lincoln lost his U.S. Senate campaign to Stephen A. Douglas. Financial necessity forced him to pay more attention to his legal career in the aftermath of this political defeat. Practicing law, however, had lost some of its luster after the political-high of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. As the foremost Republican in Illinois, Lincoln felt an obligation to lead the fractious Illinois Republican political alliance and craft a vision for party success in 1860. Lincoln was particularly concerned about Douglas’s attempts to position himself as a centrist presidential candidate who could siphon off some of the fledgling Republican Party’s conservative-to-moderate-leaning internal factions.

In early September 1859, Lincoln declined an invitation to speak in Illinois citing the necessity of devoting himself to private business. However, two things occurred in September that changed Lincoln’s mind. Harper’s Magazine published his arch-rival’s article that extolled the political virtues of popular sovereignty. Ohio Democrats also invited Douglas to campaign for state candidates. These two events compelled Lincoln to confront the Little Giant, albeit indirectly.

There was no formal head-to-head continuation of the Lincoln-Douglas debates in September 1859, but Lincoln shadowed his nemesis throughout the Buckeye State, and delivered speeches in Columbus and Cincinnati following Douglas’s wake. On September 16 and 17, Lincoln spoke at the Ohio capitol, Dayton, and briefly at Hamilton. The overall texts of these speeches were similar to one another, and presented sharper arguments than Lincoln first introduced during the formal debates in 1858.

Of all the oratory Lincoln delivered during this circuit, his Cincinnati speech on the evening of September 17, 1859 stood out from the rest, as he crafted his address to speak directly to the many southern Ohioans and Kentuckians in the audience. It was probably the best attended speech during his tour through the state. The speech also reached a much larger audience when newspapers throughout the North widely reprinted and commented on the Cincinnati address. The text so thoroughly saturated the 19th-century news network that few journalists covered the Indianapolis speech that he gave two days later.

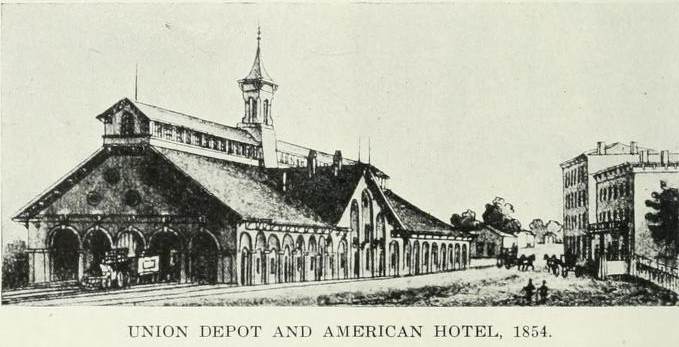

On the morning of September 19, 1859, Abraham Lincoln, his wife, and one of their sons departed Cincinnati for Indianapolis. They arrived at the Union Depot in the Hoosier capital at four o’clock. A party of political friends, led by Atlas editor John D. Defrees, welcomed the Lincolns as they disembarked. The hosts escorted their visitors across the street to the American Hotel (located near present-day 18 W. Louisiana St.) where they would spend the night.

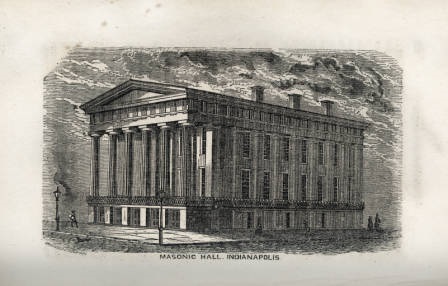

At seven o’clock that evening, an audience packed the Masonic Hall (then located on the southeast corner of Washington Street and Tennessee, which is now Capitol Avenue) to hear the Illinoisan speak. Among those in attendance were political dignitaries from both sides of the aisle, including Indiana’s Democratic Governor Ashbel P. Willard, Lincoln’s future cabinet member Caleb Blood Smith, future Indiana governor Oliver P. Morton, and Congressman Albert G. Porter (also a future governor). Although not mentioned in newspaper coverage as being in attendance, the Atlas reported that Henry S. Lane registered at a hotel that day. Most likely he attended too. If Lane was in the audience, then his presence would be of interest since he became an instrumental lobbyist for Lincoln’s presidential nomination at the 1860 Republican National Convention, and later as a U.S. Senator during the Civil War he voted for many of President Lincoln’s legislative proposals.

One wonders how Lincoln appeared and sounded to his Midwestern audiences during the late summer of 1859. The descriptions of Lincoln in the Indianapolis newspapers are somewhat limited. However, the audience’s impression of the orator were perhaps not unlike the Democratically leaning Cincinnati Enquirer‘s colorful introduction of the then not-so-well-known Lincoln to their readers:

“Hon. Mr. Lincoln is a tall, dark-visaged, angular, awkward,

positive-looking sort of individual, with character written on his face and energy expressed in his every movement. He has the appearance of what is called…a Western man – one who, without education or early advantages, has risen by his own exertions from an [sic] humble origin….He makes no pretension to oratory

or the graces of diction, but goes directly to his point…regardless of elegance or even system….With orthoepy [correct pronunciation of words] he evidently has little acquaintance, pronouncing words in a manner that puzzles the ear sometimes to determine whether he is speaking his own or a foreign tongue.”

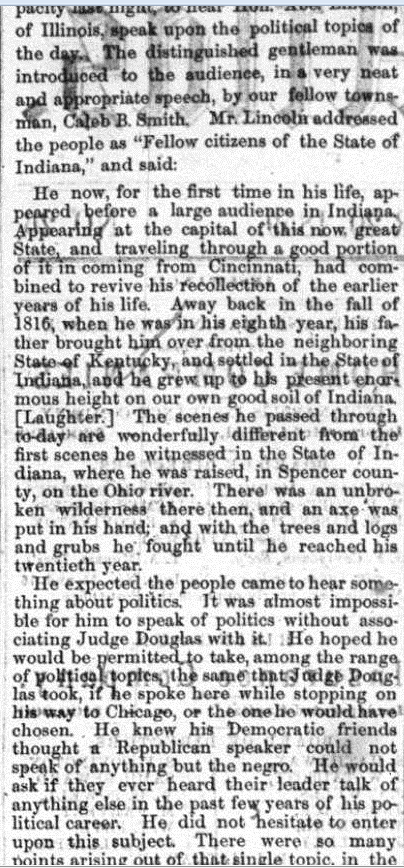

After Lincoln’s old congressional colleague Caleb Smith introduced the lecturer to the Indianapolis crowd, Lincoln opened his address with some reminiscences of growing up in Indiana. The Atlas, the best extant source for this speech, reported his words in the third person:

“Away back in the fall of 1816, when he was in his eighth year, his father brought him over from the neighboring State of Kentucky, and settled in the State of Indiana, and he grew up to his present enormous height on our own good soil of Indiana. [Laughter.] The scenes he passed through to-day are wonderfully different from the first scenes he witnessed in the State of Indiana, where he was raised, in Spencer county, on the Ohio river. There was an unbroken wilderness there then, and an axe was put in his hand; and with the trees and logs and grubs he fought until he reached his twentieth year.”

The Democratic-leaning Sentinel, while not fully reporting on Lincoln’s oration, did supply a few anecdotes from Lincoln’s youth in Indiana that the Atlas omitted. The Sentinel supplemented:

“[H]e had chopped wood, raised log cabins, hunted bears, drank out of the same bottle as was the fashion of those days, with the woodsmen of Indiana for years. He gave a graphic account of a bear hunt in the early days of this wooden country, when the barking of dogs, the yelling of men, and the cracking of the rifle when Bruin was treed, would send the blood bounding through the veins of the pioneer. Those were the days when friendships were true, and he did not think any other state of society would ever exist where men would be drawn so close together in feeling and affection.”

It is an interesting addition considering Lincoln had authored a poem about a bear hunt, and evidently the incident left quite an impression on him.

Lincoln stopped with his reminiscences, and admitted that he expected that his audience came to hear him say something about politics. At this point, he transitioned into a critique of Stephen Douglas’s advocacy of popular sovereignty. Lincoln opened his political remarks by recalling his famous words: “this government cannot endure permanently, half slave and half free; that a house divided against itself cannot stand.” He pointed out that Douglas had critiqued this thesis, and counter argued, “Why cannot this government endure forever, part free, part slave, as the original framers of the constitution made it?” Lincoln set out to answer Douglas’s question over the next two hours.

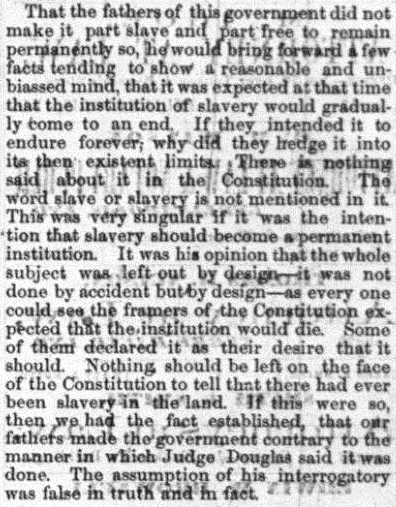

Lincoln reasoned that the U.S. Constitution was silent about slavery’s continued existence in America, and he disputed Douglas’s contention that the country was to endure “part free, part slave.” Lincoln’s main support for this argument was legislation near and dear to the history of Indiana: the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which prohibited the introduction of slavery into the Northwest Territory. Lincoln correctly pointed out that the Second Continental Congress passed the ordinance at the same time as legislators were crafting the U.S. Constitution. Therefore, Lincoln maintained,

“There was nothing said in the Constitution relative to the spread of slavery in the Territories, but the same generation of men said something about it in this ordinance of ’87, through the influence of which you of Indiana, and your neighbors in Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan, are prosperous, free men….Our fathers who made the government, made the ordinance of 1787.”

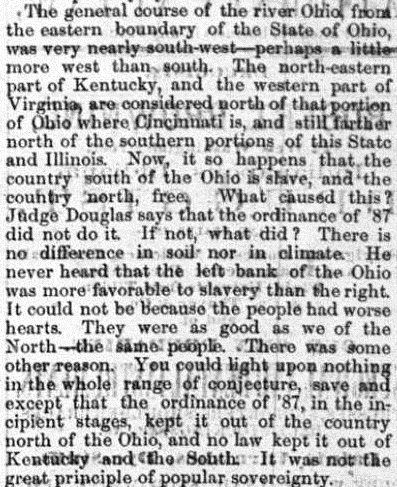

Lincoln proved to be an astute student of Indiana history, and related to his audience that a few Indiana Territory residents had once petitioned Congress to amend the ordinance to allow for the introduction of slavery. Lincoln likened this to the residents trying to exercise popular sovereignty. Yet in this case, Congress denied the petition. Lincoln reasoned, “[H]ad it not been for the ordinance of ’87, Indiana would have been a slave State.” He thereby refuted Douglas’s key political doctrine, by citing an example where the federal government had prohibited the spread of slavery, and ignored the supplications of some citizens seeking to exercise popular will. “Popular sovereignty,” Lincoln argued, “has not made a single free State in a run of seventy or eighty years [of the nation’s existence].”

In addition to focusing on popular sovereignty, Lincoln’s speech also focused on economics by contrasting slave labor and free labor. Lincoln summed up Douglas’s popular sovereignty in this way: “If one man choose[s] to make a slave of another man, neither that other man [n]or anybody else has a right to object.”

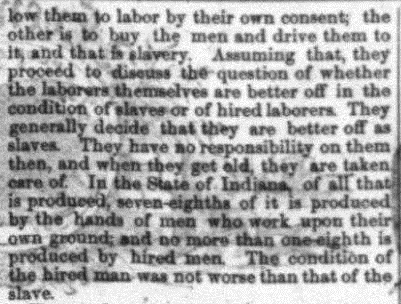

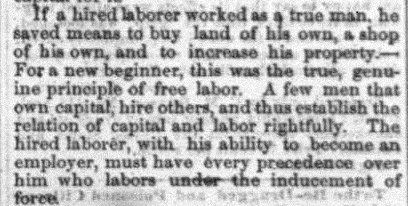

For Lincoln, that was a dangerous proposition. As a counter to this prospect, he praised the merits of free labor. Citing Indiana’s labor force, Lincoln said, “[O]f all that is produced, seven-eighths of it is produced by the hands of men who work upon their own ground; and no more than one-eighth is produced by hired men. The condition of the hired man was not worse than that of the slave.” Lincoln recalled his own work in Indiana as a hired man, and assessing his own experience at that time he did not consider himself worse off than a slave. He concluded:

“Men who were industrious and sober, and honest in the pursuit for their own interests, should after a while accumulate capital, and after that should be allowed to enjoy it in peace, and if they chose, when they had accumulated capital, to use it to save themselves from actual labor and hire other people to labor for them, it was right.”

At this time and before this audience, Lincoln spoke out against slavery not on moral grounds, but on economic grounds. Near the end of his two hour address, he said, “The mass of white men were injured by the effect of slave labor in the neighborhood of their own labor.” In other words, free labor’s value was depressed because of the existence of slave labor in the United States.

After Lincoln concluded, Oliver Morton took the stage to say a few words, but on account of the lateness of the hour, he kept his remarks brief. The next day the Lincolns continued their westward journey home to Springfield. The Indianapolis press, both Republican and Democratic organs, gave accounts of the previous night’s events, but other papers largely ignored the future president’s remarks.

In the grand scheme of things, one could conclude that Lincoln’s visit to Indianapolis in 1859 was rather insignificant. Chalk it up as one of those “George Washington slept here” historical moments. However, there is another interpretation of his visit, which adds historical significance to it. Historian Gary Ecelbarger in a Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association article argued against the common narrative that Lincoln’s Cooper Union Speech delivered in New York City in February 1860 was the speech that made Lincoln president. Ecelbarger persuasively argues that before Lincoln could get an east-coast endorsement for his candidacy, he first needed to mobilize political support among Midwesterners. Obviously, Lincoln was a well-known figure in Illinois politics, but his first deliberate and substantial politicking outside of his home-state’s borders started with his September 1859 trip to Ohio and Indiana.

These speeches were the first of about 30 addresses Lincoln delivered in eight states and the Kansas Territory in the nine months leading up to his nomination for president in May 1860. As Ecelbarger interpreted it, “[This] is evidence that Lincoln sought to increase his exposure outside of Illinois for a run for the presidency.” In this light, Lincoln’s visit to Indianapolis takes on greater significance, as he introduced himself to the Hoosier demographic that would aid his political ascent. Many of the Republican attendees who heard him that night in Indianapolis would become influential brokers in helping him secure the presidential nomination, electoral influencers that would enable him to carry the Hoosier state in the general election, and strong backers of his executive and military policies as president during the Civil War.

To read the full text of Lincoln’s Indianapolis speech, click here. View summaries of some of Lincoln’s most poignant assertions in his Indianapolis speech via the Atlas: