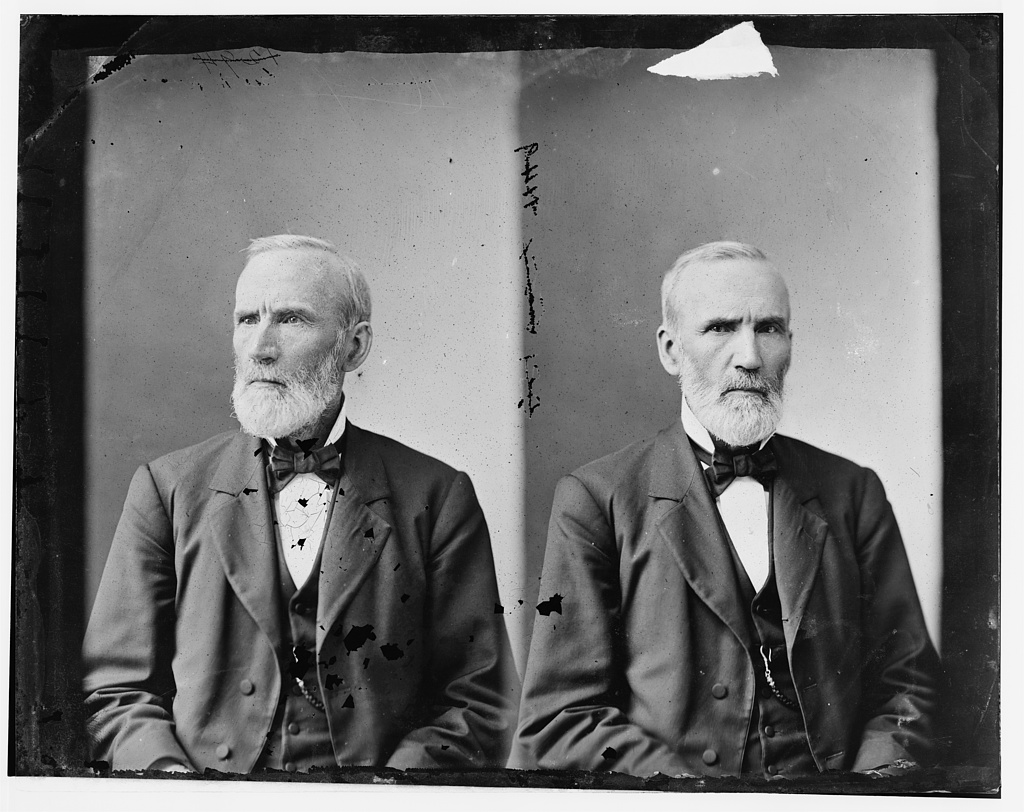

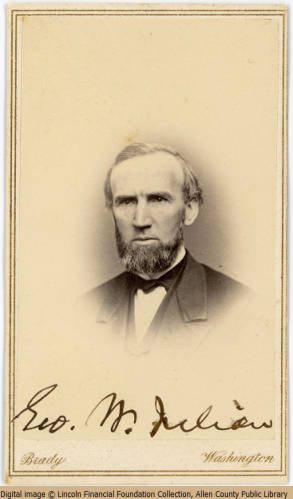

Henry S. Lane was the consummate politician for the turbulent times that spurred him into action. He regularly put party before personal ambition and was modest enough to affect change from behind the scenes with little glory. He was, perhaps more than any of the other political players involved, the prescient architect responsible for creating the Indiana Republican Party in the 1850s. But he is often overlooked and overshadowed by more dramatic characters. He did not make bold and controversial decisions like Oliver P. Morton. He did not bravely stand in opposition to slavery like George Washington Julian. Instead, he was a discerning compromiser and a shrewd political operative, essential qualities in a period marked by division and the gathering clouds of Civil War. Perhaps no man except Lane could have united the disparate factions squabbling over an array of issues to create a stalwart party able to challenge the Southern-sympathizing Indiana Democrats.

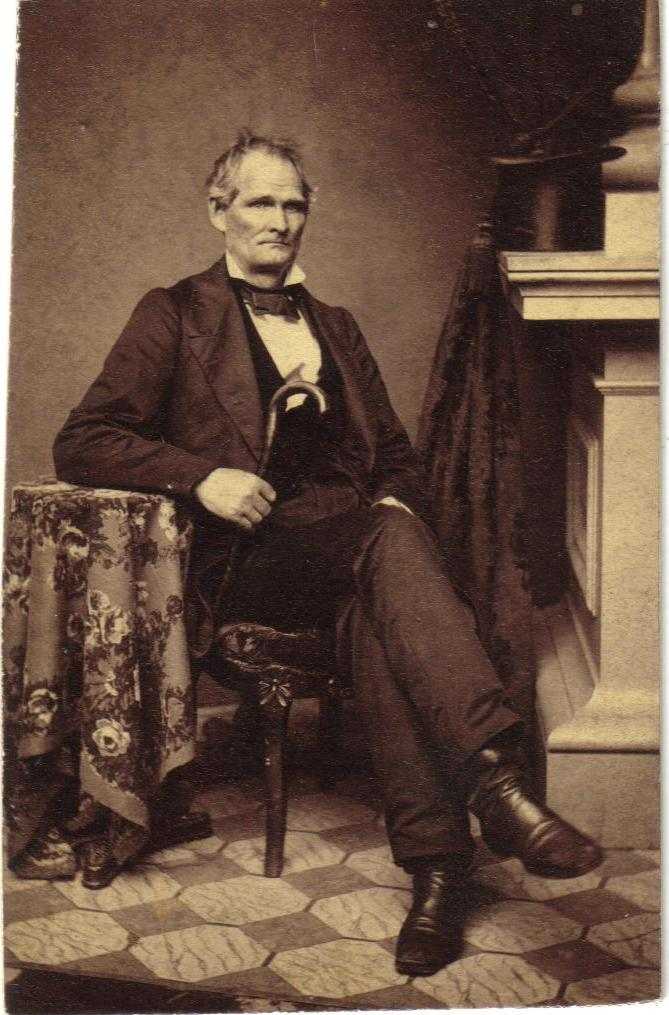

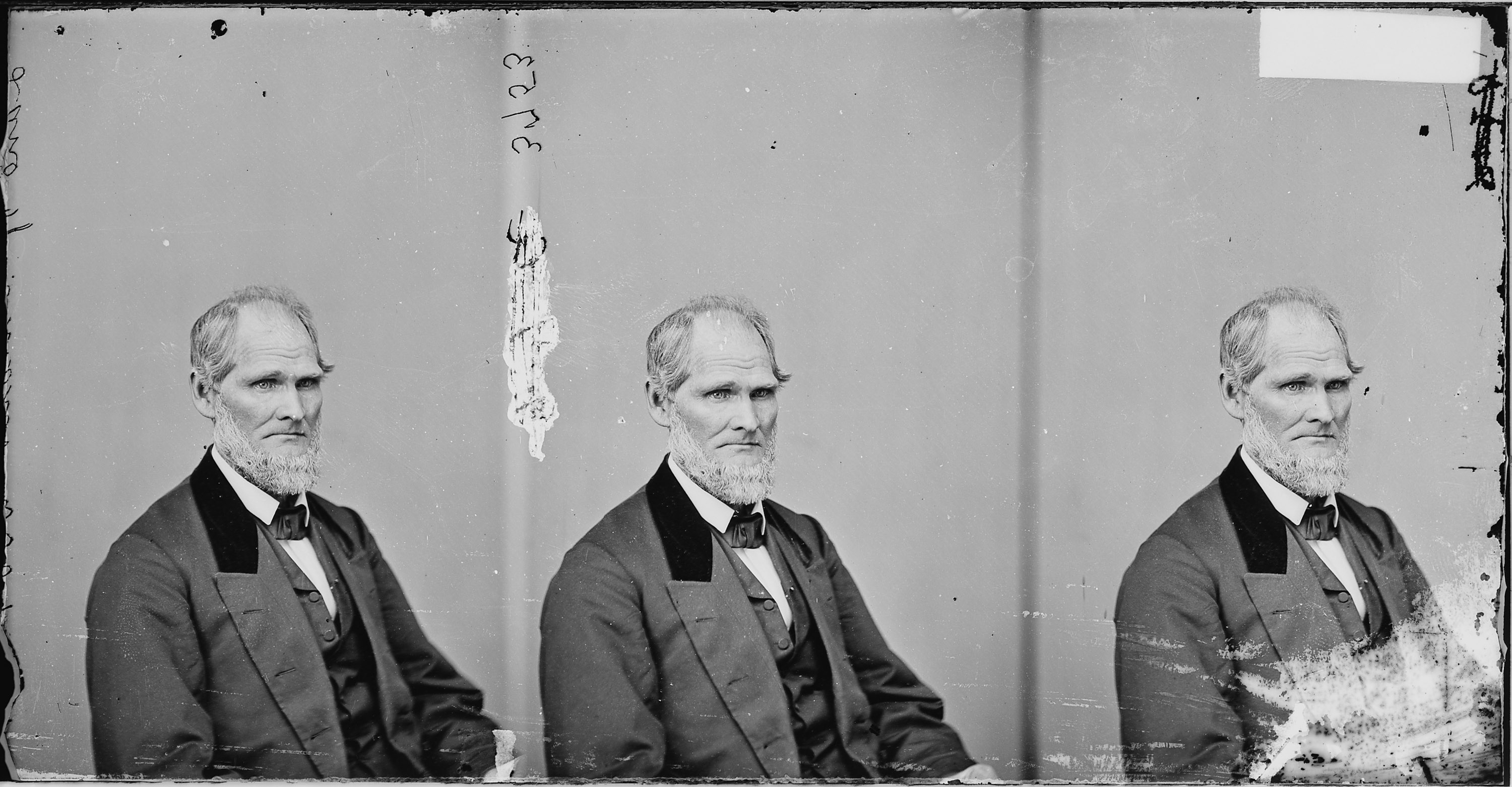

From such a grand description, one might picture Lane as a stately figure in the vein of peers such as Thomas A. Hendricks or Schuyler Colfax. However, Lane’s outward appearance did not reflect his astute political brain. He was tall, skinny, and pale. He was missing his front teeth and, in donning a blue denim suit, he did nothing to craft the appearance of a statesman. On top of everything, he chewed tobacco, a custom associated with the antebellum South.

This seemingly unimpressive figure, however, delivered some of the finest speeches ever orated by a Hoosier politician. For example, the Fort Wayne Standard described his 1854 keynote address at the People’s Party Convention as “soul-stirring and eloquent” and lamented their inability to describe his language sufficiently. His political savvy and oratory skills played no small part during one of the most exciting and tempestuous periods of Indiana political history.

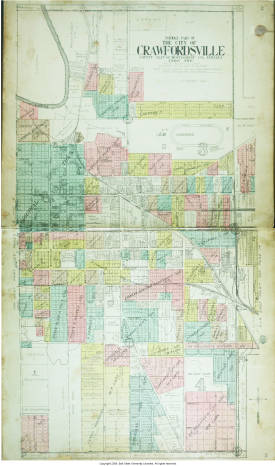

Henry Smith Lane was born February 24, 1811 in Kentucky. By 1834, he settled in Crawfordsville, Montgomery County, Indiana, where he would maintain his permanent residence for the rest of his life. He quickly rose to prominence in Crawfordsville. He gained admission to the Indiana bar soon after arriving in the community. In 1837, at the age of twenty-six, he won a seat in the Indiana House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party.

On August 3, 1840, as the result of a special election, Lane won an open seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In Congress, he caucused with fellow Whigs such as former President John Quincy Adams, future president Millard Fillmore, fellow Hoosiers Richard W. Thompson, and ex-governor David Wallace. Lane won re-election to a full term on May 3, 1841 and served until August 6, 1843. Historian Walter Rice Sharp described Lane’s time in the U.S. House: “He delivered few speeches and introduced no measures of his own. But upon occasion he would launch forth with an impromptu outburst of feeling which indicated a depth of conviction.” Apparently, Lane’s limited but impassioned participation was enough to earn the respect of his idol and Whig Party leader Henry Clay.

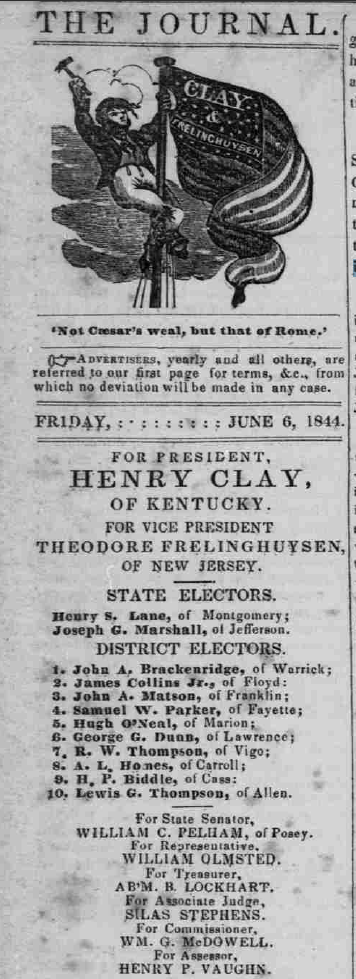

When Clay won the Whig Party’s presidential nomination in 1844, Lane took to the campaign trail. Although he recently considered dropping out of politics due to a personal tragedy, Lane consented to be named as a candidate for state elector on the Whig ticket. He traveled across Indiana, and delivered public speeches in support of Clay for president. For example, the Evansville Journal reported on a June meeting to ratify Clay’s nomination at Tippecanoe Battle Ground: “Hon. Henry S. Lane of Montgomery, being loudly called for, took the stand and addressed the immense multitude in exposition of the principles and aims of the Whig party.” After Lane enthusiastically praised Clay and the party, the Indiana Whigs heartily ratified the nomination. He increased his efforts on behalf of Clay in the fall and one can follow his speaking trail through the newspapers using Hoosier State Chronicles. From August through October the (Brookville) Indiana American reported on Lane’s appearances at “Whig Mass Meetings” in Rockville, Lafayette, Logansport, Goshen, Fort Wayne, LaPorte, and Terre Haute.

The Democratic Party, however, was re-gaining dominance in Hoosier politics. The Whigs lost major ground in the 1844 state elections. In the presidential election, Hoosiers reflected the national choice of Democrat James K. Polk over Clay. Among other issues, the Whig Party failed to sense a changing economic climate. The country was in an expansionist mindset and the Democrats catered to this hunger for land and the imagined opportunities associated with it. Polk advocated for the addition of Texas and Oregon into the Union, satisfying the public’s desire for expansion, but also rocking the delicate balance of Slave and Free states that would soon lead to the Civil War. Lane had thought little about slavery thus far, and it would have been hard to imagine at this point in time, that he would one day unite the anti-slavery factions in Indiana.

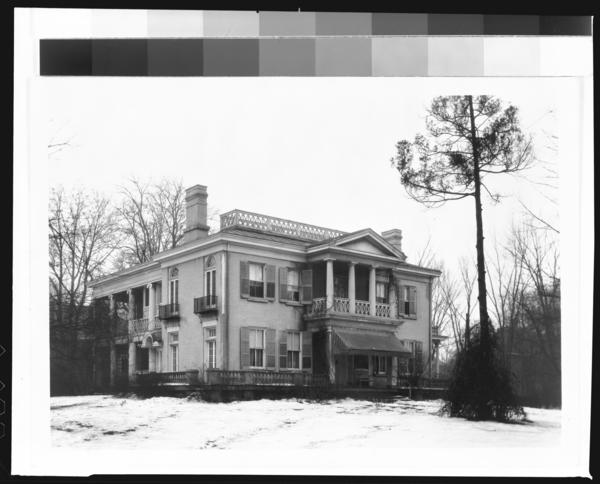

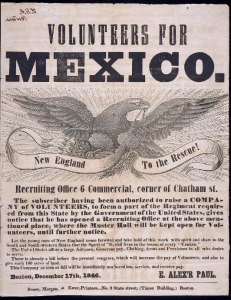

Clay’s defeat reinforced Lane’s earlier desire to withdraw from politics. In 1845, he re-married (after being widowed) and focused his efforts on building a large white house in Crawfordsville which he named Lane Place. It was built to last – it still stands – and to serve as a quiet retreat from the national stage. His country, however, soon needed him. According to Lane biographer Michael Hall, Lane objected to Polk’s declaration of war on Mexico in 1846 on partisan political grounds. Yet as a patriot, he felt called to serve. He organized a group of volunteers who assembled outside Lane Place in June of 1846 and left home for war.

Over a month later, Major Lane and the First Infantry Regiment of Indiana Volunteers arrived at the Texas-Mexico border. The camp they found there was “hell upon earth,” according to Lane. The regiment waited in vain for months to be ordered into battle. Meanwhile, Lane and the other officers watched as their troops contracted and succumbed to malaria, dysentery, yellow fever, and other diseases. Lane wrote in his journal, “We shall bury a great many of our best men before we leave this miserable camp.” Despite repeated requests for an active assignment, Lane (now a lieutenant colonel) and his men returned to Indiana after ten months of inaction, disillusioned by their experiences. According to Hall, this event also embittered Lane to both the Whig and Democratic parties and “the bureaucratic bungling that caused the inefficiency he witnessed and had contributed to the war’s cause.” By 1847, Henry S. Lane anticipated the need for a new political party, but the climate would not be ripe for another seven years.

Zachary Taylor was the last Whig to win the presidency when he defeated Democrat Lewis Cass in the 1848 election. The new president was also a slaveholder. Hall claims that Lane “constantly criticized” Taylor, and thus further distanced himself from the Whig Party. However, a search through Indiana newspapers using Hoosier State Chronicles shows that Lane, putting party before personal sentiment, offered half-hearted support for Taylor. For example, the Indiana State Sentinel reported in February 1848, that Lane spoke to an audience of “Taylorites” in Crawfordsville. Lane described Taylor as “an American of capacity, of honesty, and merit” and reported that he offered his support for the obscure reason that “as the people are all going for him, I wish to keep out of the crowd.” However, Lane seemed more enthusiastic about his party that fall. The (Brookville) Indiana American reported on a gathering of many leading Midwestern Whigs and a large audience “who had left their shops, farms, and daily occupations to spend a day of two in honor of Zachary Taylor – the people’s candidate for the Presidency.” The paper described Lane, one of the main speakers at the event: “[T]hat gallant Whig champion and eloquent orator of our own State, Henry S. Lane, of Montgomery [County], was called for, and mounting a table at the door, he poured forth a flood of political truths which elicited shouts of applause! The old Whig fire seemed to be rekindled anew upon every altar, and not until a late hour, was he permitted to leave the stand.”

Political defeat, however, soon doused Lane’s fire. His 1848 loss to Joseph E. McDonald for the U.S. House of Representatives made clear that, much like the Whig Party itself, his political and moral stances were in flux. He was a Whig “in name only,” according Hall, but newspapers such as the Indiana State Sentinel recognized him as “the most prominent member of that body.” More importantly, he had yet to take a clear position on slavery. While the Montgomery (County) Journal called him a “champion of human rights and freedom” who would check the expansion of slavery, the Sentinel noted that he had made no anti-slavery promises on the campaign trail. The paper reported that they hoped he would “define his position . . . and . . . openly declare whether he will support Taylor’s bidding or not.” Lane lost the election, and by this point in history, Indiana was solidly Democratic.

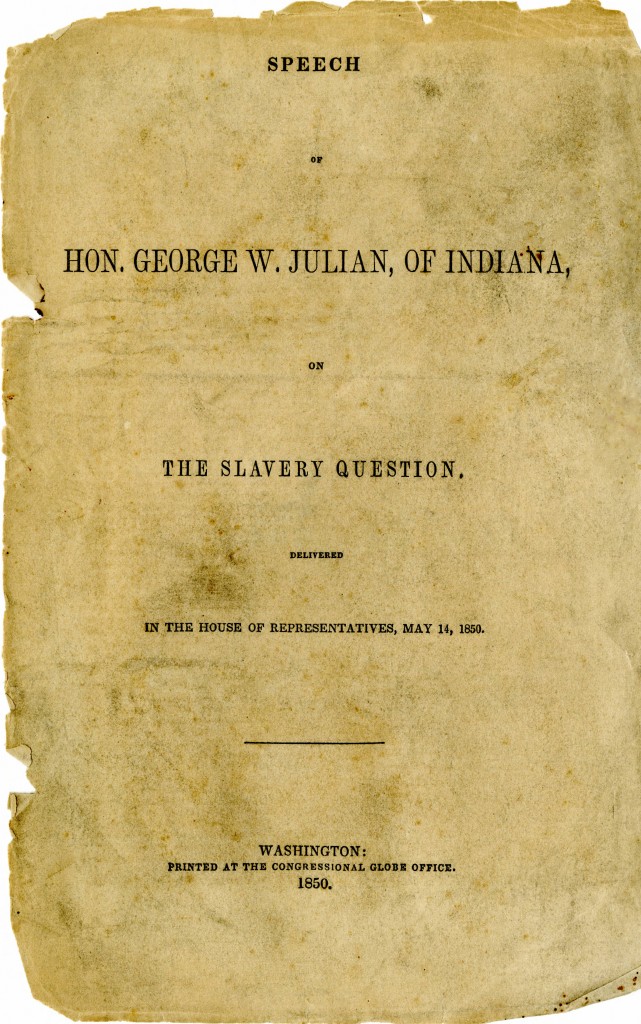

Lane’s response to the Compromise of 1850 epitomized his ambivalent stance on slavery. Like most Whigs, Lane supported this set of bills that temporarily eased tensions between pro and anti-slavery interests at the expense of actually solving the problem of slavery. Like Clay, Lane was morally opposed to the institution of slavery but politically only opposed the extension of slavery into new U.S. states and territories. (This is a marked contrast to George Washington Julian, for example, a staunch abolitionist who fought to rid the nation of slavery completely.) Also like Clay, Lane did not imagine the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which put limits on slavery’s expansion in the U.S. Territories, would ever be repealed. All Whigs, however, did not see the issues the same way as Lane and Clay. The Compromise of 1850 highlighted the sectional divisions in the Whig Party, while at the same time creating an uneasy peace. Henry Clay’s death in 1852 served as a harbinger of the Whig Party’s fate. A few short years thereafter, the party membership fractured over a piece of legislation that destroyed the tentative sectional truce.

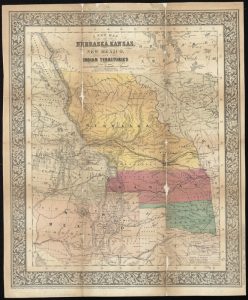

In 1854, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act which repealed the Missouri Compromise. The bill was sponsored by Illinois Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas (who would later run for president against Abraham Lincoln) and signed into law by Democratic President Franklin Pierce. While initially a huge setback for the anti-slavery movement, opposition to this law and to the Democratic administration worked to mobilize disparate political groups against a common cause. This was the perfect climate to organize the new party that Lane and others had envisioned years earlier.

Among those Americans who were united against the extension of slavery into new territories their opinions on slavery itself varied widely. Many anti-slavery adherents opposed the western spread of slavery, but had little interest in the fate of enslaved peoples in the South. Whites who worked in agriculture and industry opposed slavery’s expansion because they did not want to compete with slave labor in the North or in new territories. For the anti-slavery politicians and electorate who favored emancipation, there were debates on how to accomplish this. Some groups favored emancipation only over an extended period of time. Even within this “gradual emancipation” position there were debates as to whether or not slaveholders should be compensated or not as a result of their loss of “property.” Even if an anti-slavery faction favored emancipation they often advocated that the freed African Americans should be removed from America and colonized in Africa. Only a small percentage of anti-slavery supporters abhorred the institution as an affront to God and labored for its immediate abolition and citizenship rights for African Americans. Despite these sometimes vastly different positions, the desire to stop slavery’s spread was a unifying aim, and in July 1854, former Whigs, anti-slavery Democrats, Free Soilers, and others organized to form a new national party: the Republican Party.

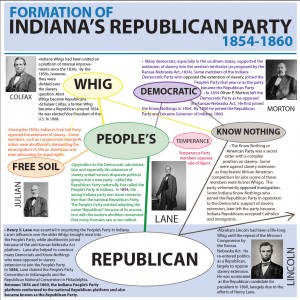

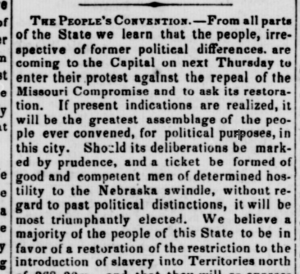

In Indiana, Lane and other prominent ex-Whigs called for a state convention to be held July 13, 1854 for the purpose of organizing a new party. Historian Walter Sharp wrote that “Lane, with his wealth of persuasive eloquence and his unblemished character, was clearly the prime mover of this inner council.” That day, ten thousand people reportedly rallied at Indianapolis to protest the Kansas-Nebraska Act. These included Hoosiers favoring political issues that ranged from alcohol-adverse temperance advocates to anti-Catholic, xenophobic Know-Nothings to defecting Democrats to staunch abolitionists. It was clear to Lane that the new party must include all of these diverse political voices, and unite them against slavery’s expansion. Thus, Indiana’s arm of what would in ensuing years become the Republican Party, had to be more moderate in order to be more inclusive. Lane and other leaders chose to call it the People’s Party. They reasoned that by avoiding the name “Republican” they could avoid the association with the eastern abolition movement that many Hoosiers saw as too radical.

Democratic newspapers had their own, more colorful names, for the new party. The Indiana State Sentinel referred to the July meeting as the “Isms Convention” and the “Great Mongrel Convention,” criticizing the sheer number of different ideologies that the party was attempting to reconcile. Another Democratic paper, the Worcester (Massachusetts) Transcript, called it “a Free Soil Convention in disguise.” The Sentinel also hyperbolized, calling the People’s Party the “Abolition Free Soil Party” in an attempt to scare off the conservative Know-Nothings and defecting Democrats.

Despite the efforts of detractors, the convention was a success. This was due in large part to Lane’s unifying speech where he outlined the platform of the new party. He appeased the prohibitionists by calling for a liquor ban and the Know-Nothings by calling for a “lengthy citizenship” process, all without offending the German immigrant members in their midst. Mostly, however, he set the party in opposition to the detested Kansas-Nebraska Act and the expansion of slavery into the territories. Lane biographer Hall explained that his speech, “Molded the various confederations of political doctrine into one shaky, but significant movement.” The (Huntington) Indiana Herald praised Lane’s speech and delighted over his criticism of Democratic U.S. Senator John Pettit who recently spoke in Indianapolis in support of the reviled Kansas-Nebraska Act and famously stated during the Senate debate on the act that Jefferson’s statement included in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” was “a self-evident lie.” The paper reported:

[Lane’s] address was of the most soul-stirring and eloquent character. We cannot pretend to give his language, and if we could, no one, unless they heard him, could form an idea of his style oratory. His defense of the glorious Declaration of Independence from the foul aspirations of Petit [sic], was the finest specimen of terrible denunciations that we have listened to for many years. Had that individual been present, as brazenfaced as he is, he must have wilted down under the Atlas load of scorn piled upon him by the eloquent Lane.

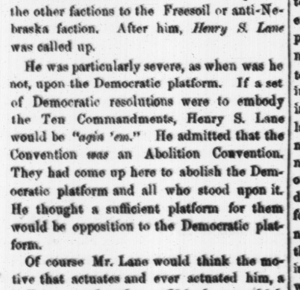

Of course, the Democratic Indiana State Sentinel had a different view of Lane’s speech. The paper complained that Lane’s stance was simply to oppose anything the Democrats advocated. The Sentinel also made fun of Lane’s folksy, rustic manner of speaking:

If a set of Democratic resolutions were to embody the Ten Commandments, Henry S. Lane would be “agin ’em”. . . If he knows which side the Democrats are on, he is always on the other side, and his only guide has ever been opposition to Democracy.

In a way, the Sentinel was right. Lane knew that perhaps the only thing this heterogeneous group of Hoosiers had in common, was opposition to the Democratic Party and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The official platform set forth by the People’s Party was simple. First, they opposed the extension of slavery. Second, they advocated for laws to “suppress the traffic in ardent spirits as a beverage.” And third, they opposed everything laid out by the Indiana Democratic Party during their recent convention. One example of the platform’s moderation was seen when the abolitionist George Washington Julian introduced a minority report calling for a stronger stance against slavery and the Fugitive Slave Law. The convention quickly tabled Julian’s request. Nonetheless, the Indiana People’s Party rode their non-traditional platform to success in the 1854 elections statewide; they took nine out of eleven congressional races and gained a majority in the lower house of the Indiana General Assembly.

Lane exerted great influential in steering the new party toward a moderate stance on slavery. He recognized that most of Indiana’s electorate saw the abolition movement as too radical. At this delicate time, he was careful to speak only against the extension of slavery, and did not advocate for its abolition. In 1855, he wrote to Indiana Congressman Schuyler Colfax, “We must resist the encroachment of Slavery, if we would preserve the rights of Freedom.” Despite his moderation, Democratic papers charged Lane with being an abolitionist. While Lane was certainly not an abolitionist, his views on slavery were shifting towards opposing the institution itself, not just its extension.

During the 1856 election year Lane remained a key figure in the Indiana party and began making waves nationally as well. In 1856, Lane chaired the People’s Party Convention in Indianapolis and the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia that nominated John C. Frémont for president (and had the crafty campaign slogan: “Free labor, free soil, free men, Frémont”). In his 1856, Lane addressed the Republican National Convention, and reiterated that the party opposed only extension of slavery, not its abolition, but added that he believed the Declaration of Independence to be “an anti-slavery document.” He described the Republican Party as representing “every shade of Anti-slavery sentiment in the United States” and that the party hoped to see a time when God would “look upon no slave North or South.” He continued:

Freedom is national. Freedom is the general rule. Slavery is the exception. It exists by sufferance. Where it does exist under the sanction of the law, we make no war upon it. Does that constitute us Abolitionists, simply because we are opposed to the extension of slavery? If that makes an Abolitionist, write ‘Abolitionist’ all over me.

The Crawfordsville Journal reprinted Lane’s speech. The only editorial comment the Journal provided was this: “We give it to our readers without note of comment, as it was reported for that paper. We consider it, however, a master stroke of Western eloquence. Let everybody read it.”

Back home in Indiana, Lane again demonstrated his political savvy and ability to put party before personal ambitions in an attempt to strengthen it for the 1856 election. Lane was the preferred pick for gubernatorial nominee among some party leaders for his skill, experience, and unifying effect. However, Lane knew Oliver P. Morton would be the candidate with a better chance of winning. Morton had been a Democrat until just before the People’s Party’s organization and had no record of anti-slavery rhetoric. A former Democrat was likely to draw the support moderate and disillusioned Democrats as well as former Know-Nothings, who were not thrilled with the participation of Lane and others in the Republican National Convention (as they still considered the national party too radical). Despite this creative maneuver, Morton lost the election. Democrats won the state and the national election making James Buchanan, supporter of strict fugitive slave laws and the rights of states to decide the slavery issue, the leader of a divided nation.

Over the next four years, the People’s Party aligned itself with the national platform and adopted the name “Republican.” As the Indiana party looked toward the 1860 election year, Lane looked toward Washington and a Senate seat. He also applied what he knew about offering the voters moderate candidates who could appeal to various factions. He used this knowledge when he threw the Indiana delegation’s support behind Abraham Lincoln’s nomination at the 1860 Republican National Convention. Check back for a second post on Lane and his role in Lincoln’s 1860 presidential nomination and scheme to win both the governorship and a Senate seat for his party.

For more information see:

Michael Hall, The Road to Washington: Henry S. Lane, The Rise of an Indiana Politician, 1842-1860 (Crawfordsville: Montgomery County Historical Society, 1990).

Walter Rice Sharp, “Henry S. Lane and the Formation of the Republican Party in Indiana,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 7:2 (September 1920): 93-112.