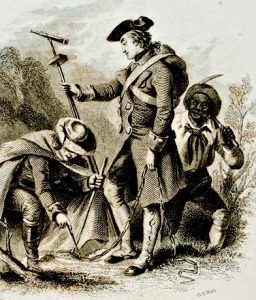

A small group of men made their way through the thick southern Indiana forest dragging chains in their wake. Once in a while, they stopped to score a tree, plant a post, and record their progress. For those residents of the Indiana Territory who witnessed this bizarre parade in the fall of 1804, this group represented vastly different futures. For Thomas Jefferson and other leaders of the young United States, this group of men sent to survey the Indiana Territory represented the spread of democracy. For the indigenous people who first called this land home, the marks cut and burned into the trees represented the impending and permanent loss of that home. Despite their disparate perspectives, both would soon see the redefinition and reorganization of the landscape by the rectangular survey system.

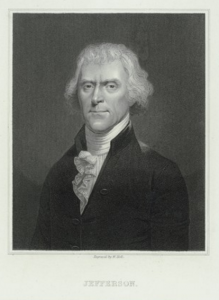

After the American Revolutionary War and via the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the British surrendered their claim to the thirteen colonies and ceded a vast amount of western and southern territory to the young United States. In order to grow the republic and repay war debt, the new government needed a system of organizing this land for sale. In response to these needs, the Continental Congress created a committee chaired by Thomas Jefferson to create a system for surveying the new territory.

Jefferson passionately believed that the system had to make small plots of land available to the individual farmer (as opposed to large plots available only to the wealthy, to speculators, or to large companies) in order to spread democracy throughout the territory. In 1785, Jefferson wrote:

We have now lands enough to employ an infinite number of people in their cultivation. Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country and wedded to it’s [sic] liberty and interests by the most lasting bands.

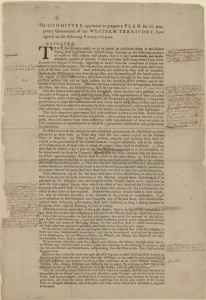

The committee’s answer was the Land Ordinance of 1784 which attempted to define and standardize surveying methods to create a grid of small plots of land across the territories. These surveyed squares could then be subdivided, numbered, and recorded for sale. In this manner, the landscape could be divided and sold to settlers unseen — that is, without the surveyor having to physically walk the entire area, mapping the land in the old system of metes and bounds (which used natural markers like trees and rivers to define property). This older system was time consuming, required the surveyor’s physical presence in a sometimes dangerous landscape, and often led to land disputes as natural markers were altered or disappeared. While the 1784 Ordinance did not become law, it did define the rectangular system and laid out the principles that would measure and divide the landscape into what it is today.

On May 20, 1785, Congress passed the Land Ordinance of 1785, a revised version of the 1784 plan which further described the system and codified a detailed survey plan which used mathematics and standardized chains for measuring. The ordinance stated that surveying would begin on the Ohio River, at a point that shall be found to be due north from the termination of a line which has been run as the southern boundary of the state of Pennsylvania.” According to historian Matthew Dennis, this rectangular survey system allowed the leaders of the young government to apply their “nationalistic, scientific, and engineering mentality in transforming the continental landscape of North America, reconceptualizing its space, subduing and organizing it, and distributing it to white yeoman farmers in the interest of national expansion, and, they believed, democracy.”

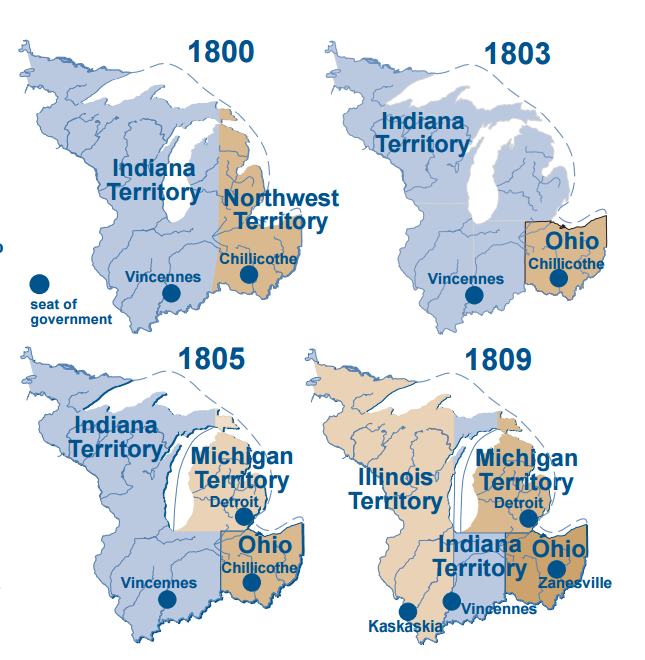

The removal of the native tribes living in the territories was the first step of the survey process. Both the proposed 1784 Land Ordinance and the adopted 1785 Land Ordinance called for American Indian removal. The United States government worked towards this end through both military action, economic pressure, and treaties in order to make space for white male settlers to farm the land. On July 13, 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, an act which created the Northwest Territory (an area that would become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota) and provided a system for settling the area to create new states.

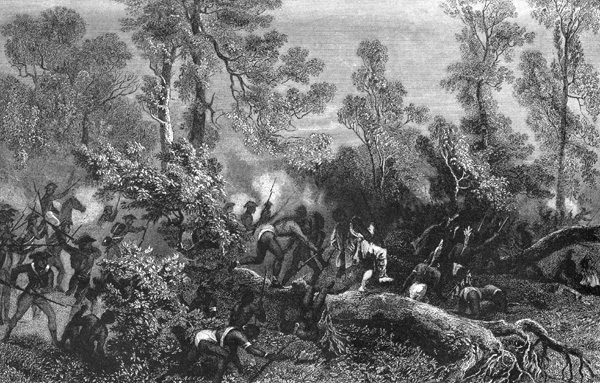

The U.S. government viewed conflict with indigenous populations in the area as the greatest obstacle to the expansion and settlement of white Americans in the territory. According to historian Eric Hemenway of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians:

Between 1774 and 1794, Indian villages in New York, Pennsylvania, Indiana and Ohio were constantly attacked by the American army and militias. The Shawnee, Delaware, Iroquois, Miami, Odawa, Wyandot and Mingo saw unspeakable violence committed against their villages during this time period. Over 100 Indian villages were burned and destroyed, leaving an unknown number of civilian casualties.

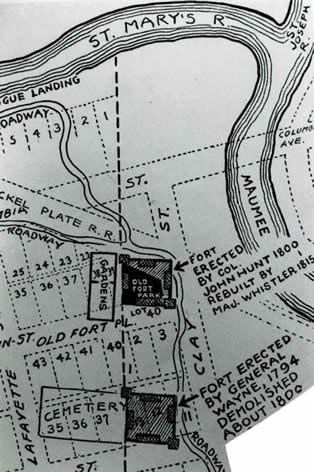

The U.S. government applied military, economic, and diplomatic pressure on native peoples to cede land and create a peace, no matter how tenuous. The military pressure was applied by President George Washington’s assignment of General Anthony Wayne to battle a confederacy led by Miami, Shawnee, and Lenape (Delaware) chiefs. After suffering major losses at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers, many tribes living in the Northwest Territory were resigned to settling for peace. This resulted in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, in which some tribal leaders ceded large sections of land in Ohio and Indiana to the United States and opened much of the area to white settlement. Many Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Chippewa, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Kaskaskia lost large portions of their homeland. Still other native leaders resisted and contested this and subsequent treaties, and would later fight to regain their land under the leadership of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa.

While the U.S. government offered payment in goods for signing the treaty, some Native Americans became dependent on these annuities as the land on which they made their living was taken from them. In some cases, they fell into debt and lost even more land as a result. This situation was often exploited by the United States government. For example, in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote William Henry Harrison:

We shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among [Great Lakes Indians] run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands.

After the Treaty of Greenville provided prospective colonists the security of peaceful settlement, Congress passed the Land Act of 1796. This legislation provided for the sale of land in the Northwest Territory. It reiterated that surveys would be conducted in areas “in which the titles of the Indian tribes have been extinguished.” It also appointed a Surveyor General directed to employ deputy surveyors.

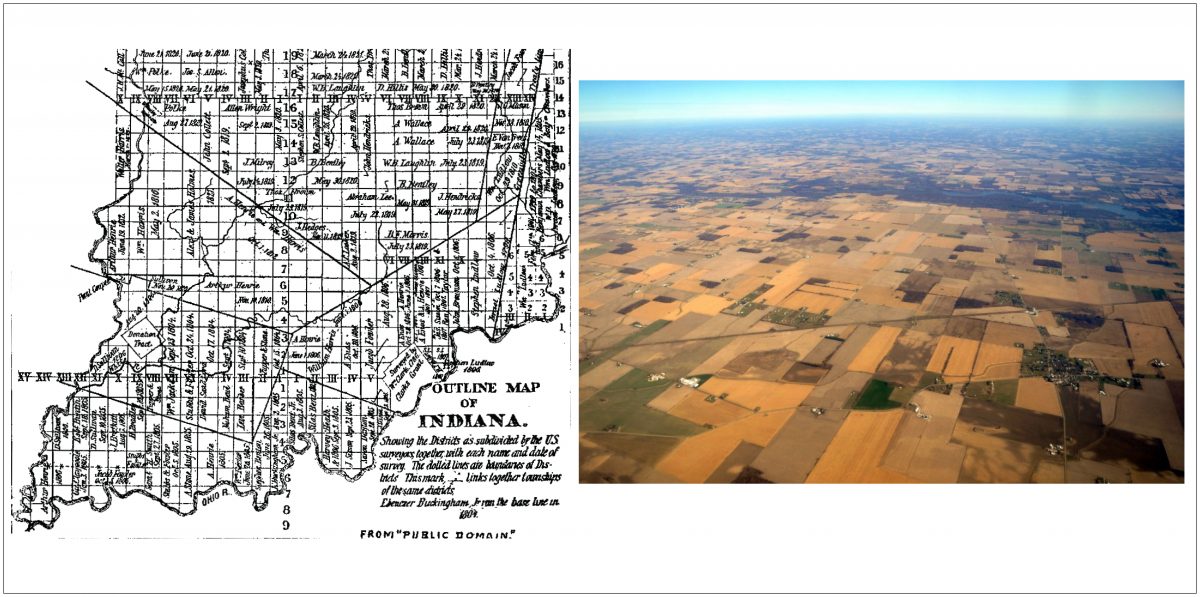

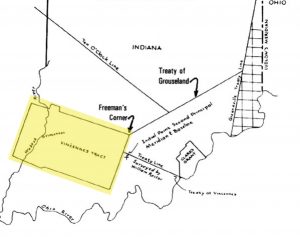

The land which would become Indiana was difficult to survey because much of it had yet to be acquired through treaty. The Vincennes Tract, an area ceded by local tribal authorities to French settlers in 1742, provided another unique obstacle. This area ran along the Wabash River and thus had been surveyed at an angle, and French settlers acquired titles to the land based upon this survey. Since 1787, the inhabitants of the Vincennes Tract regularly petitioned Congress to validate their titles. In May 1802, Congress determined that the territory should be surveyed by the rectangular method except where it had been previously surveyed. In other words, the Vincennes Tract would sit like an oddly angled puzzle piece within the rest of the rectangular pieces. The lines forming the rectangles would stop at the edge of the Vincennes Tract and then continue after it on all sides. According to survey historian Bill Hubbard, since the purpose of the rectangular survey was to organize the land for sale, there was no need to resurvey the tract.

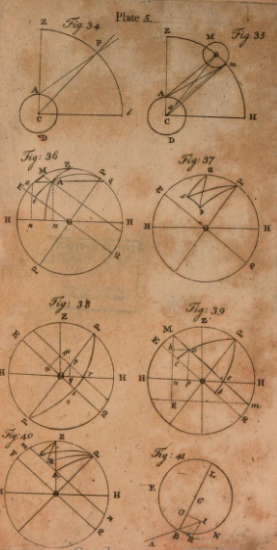

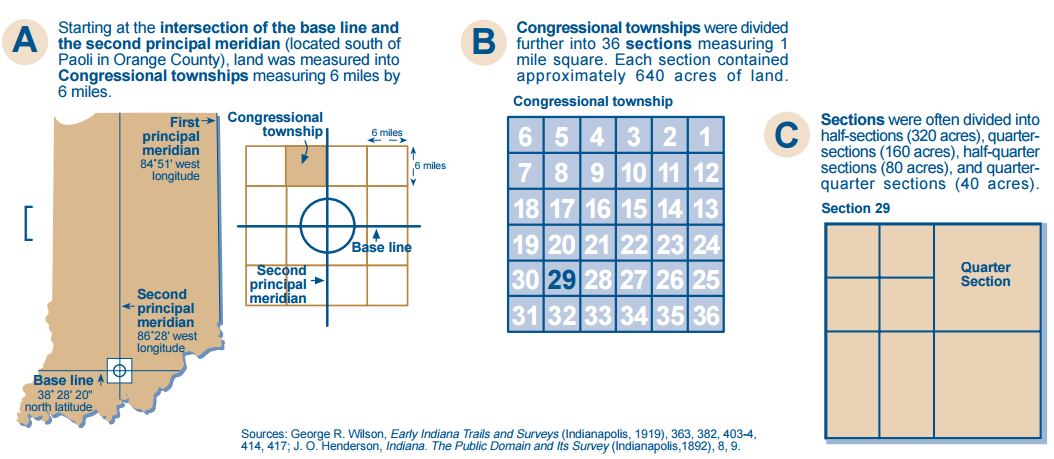

Meanwhile, in March 1803, Ohio attained statehood, which left the rest of the former Northwest Territory as the Indiana Territory. Congress wanted the Indiana Territory surveyed in full in preparation for American colonization. In June 1803, the Vincennes Tract’s boundaries were confirmed through Indian treaties and the edges surveyed. Surveying the Indiana Territory around the irregular tract became Mansfield’s first challenge as Surveyor General. U.S. government officials assumed it was a matter of time before the rest of the territory would be acquired from the Native Americans, and thus Mansfield needed to develop a technique for surveying this vast landscape that did not include the time-consuming and even dangerous physical trek through the entire landscape measuring with steps and chains. Instead, he determined that he could create a meridian and a baseline ran off the corners of the Vincennes Tract which would be the foundation of a grid made up of six-mile by six mile square plots of land called townships.

Mansfield planned a baseline that would start at the southwestern corner of the Vincennes Tract and run east-west to the edge of the territory and a meridian which ran from the southeastern edge of the tract north through the territory. The north-south line was called the Second Principal Meridian and coincides with 86° 28’ west longitude. The base line coincides with 38° 28’ 20” north latitude and became known locally as Buckingham’s Base Line. From the intersection of these lines, survey lines could be calculated every six miles in all four directions to create the grid of townships. Each township could then be further divided into one mile squares creating thirty-six sections of land. Each section contained 640 acres of land which could then be divided further in half, quarter, half-quarter, and quarter-quarter sections as needed. These plots would then be numbered and sold to settlers without the surveyor hiking the entire territory, the running of the two lines being the only physical surveying needed.

While Mansfield mathematically planned the baseline which would serve as a foundational line for the survey of the Indiana Territory, someone still had to mark the line into the landscape and take measurements. That task fell to a small crew led by deputy surveyor Ebenezer Buckingham, Jr., and he would long be remembered for his efforts. Originally from Connecticut, Buckingham migrated to Ohio in 1796 and began work as a farmhand for General Putnam. He assisted Putnum on survey trips in several Ohio counties, and in 1799, Putnam swore in Buckingham as a deputy surveyor.

In 1804, Mansfield appointed Ebenezer Buckingham to lead a crew to run the base line. They began at a point on the south-side of the Vincennes Tract and ran a line east for 67.5 miles, marking off miles and half-miles on trees. Buckingham and crew then went to the southeast corner of the Vincennes Tract and ran a line due north until they reached the baseline. When they intersected the baseline, they marked the initial point. Then, they marked section corners and half-section corners until they reached the east end of the Vincennes Tract again. They packed up for the winter and returned the next season to finish extending the baseline east twelve miles and the meridian north in September 1805. The placement of the baseline and meridian in these locations allowed Buckingham and his crew to lay the foundations for the survey system and include the Vincennes Tract in it, all without encroaching on lands that still belonged to Native Americans. After this, the townships could be numbered and the land further divided. The township numbers would be increased east and west away from the Principal Meridian and be numbered away from the Baseline north and south, starting at the Initial Point where the two lines crossed.

Because the rectangular survey clearly mapped the land, organized, and numbered it, settlers knew that any land they purchased had a secure title. This was not true in states not mapped in such a standardized way. For example, in Kentucky, the same land was sometimes surveyed multiple times in different ways giving rise to title disputes. For example, in 1808, a carpenter and cabinet maker named Thomas Lincoln purchased a farm near Nolin Creek, Kentucky. The following year, in the cabin that Thomas built on his land, his son Abraham Lincoln was born. The family soon moved to another farm, along Knob Creek for which Thomas paid cash years later in 1815. However, the titles of both his farms were challenged by competing claimants. According to Abraham Lincoln biographer William E. Gienapp, because Thomas did not have the resources to fight a possibly extensive court battle, “he simply sold out at a loss and in December 1816 moved to Indiana, where the federal government had surveyed the land.” Thus, the survey system played no small role in bringing the studious young man who would become the sixteenth President of the United States to Indiana.

Aerial View of Indiana (right) accessed Indiana Public Media,

The legacy of the survey system still defines how Hoosiers interact with the landscape today and is seen in our counties, townships, and the quilted pattern of Indiana farmland. In fact, much of the country is organized by this system. According to historian Michael P. Conzen, “Except for the original 13 colonies, Texas, and some western mountainous areas, most of the country is parceled out on the township and range system.” The methods perfected by Mansfield and executed by men like Buckingham were applied throughout the vast landscape of the United States to the benefit of some and the anguish of others. In 2018, IHB will place a state historical marker for Buckingham’s Base Line in Dubois County at one point of the line, literally inserting the story of this complex landscape back into the landscape itself – a reminder that as Hoosiers we share both the legacy of those industrious settlers who arrived following a dream of a better life in a bright new democracy and the legacy of those native peoples who were harmed to make that dream a reality.

Special thanks to Annette Scherber who contributed research for this post.