Portions of this post first appeared as an article by the author in the Indiana Jewish History journal, published by the Indiana Jewish Historical Society. The complete article, which gives much more information on her suffrage work is available here along with annotations.

Sara Messing Stern, a dedicated suffrage worker and advocate for the poor, was accustomed to being the only Jewish woman in the room. Whether organizing housing relief or mobilizing women for the vote, she applied her steady hand and organizational skills to achieve progressive results. She lived her Jewish values through her work and expressed them through her poetry. She believed that no matter a person’s faith, God called them to care for those less fortunate. For the most part, Stern thrived in the suffrage and women’s club movements, which were dominated by women of various Christian sects. However, as is often the case for Jews, she was accepted by society until she wasn’t. That is, if her peers felt she had gained too much power or if they came into conflict with her ideas, these Christian women were not above using antisemitic language and ideas to dismiss and denigrate her. Yet Stern would rise above their defamation to help Hoosier women win the vote and rebut their slander through poetry.

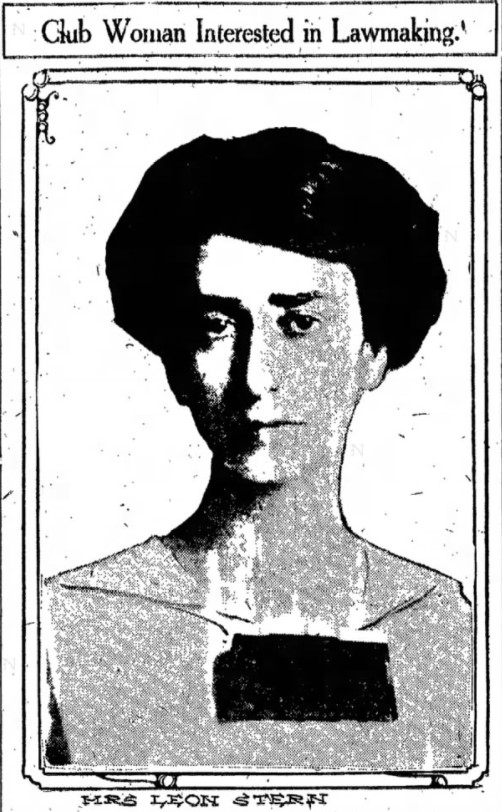

Sara was born to German Jewish immigrants Rica (née Naphtali) and Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation Rabbi Meyer Messing, who was himself an advocate of progressive reform and a supporter of women’s rights, in Indianapolis in 1879. In 1906, Sara married Leon Stern, an auditor for an Indianapolis coal company. While she took her husband’s surname “Stern,” she also kept her maiden name “Messing,” maintaining a link to the Messing ancestral line of prominent rabbis as well as her individual identity. While newspapers sometimes referred to her as “Mrs. Leon Stern,” primary sources show that within the organizations where she held power, she presented herself as “Sara Messing Stern.”

Stern first made her mark in Indianapolis through philanthropy and was especially concerned with the welfare of women and children. She advocated for reforming child labor laws and tenement housing, and served as a probation officer, aiding juvenile offenders and guiding them back to a productive path. She believed in second chances and recognized that the poor faced great obstacles. She stated in 1912, “I have found in dealing with people who have sinned that we are too quick to judge by what we see done, rather than the things overcome.”

Stern worked with many city charities and was a leading member of the local section of the National Council of Jewish Women. As a Council representative, Stern attended a 1909 reception for the firebrand suffragist Grace Julian Clarke, who had been recently elected president of the Indiana Federation of Clubs. Stern and Clarke would continue to cross paths through club and charitable work over the next few years. In fact, a deepening friendship with Clarke may have brought Stern into more active suffrage work.

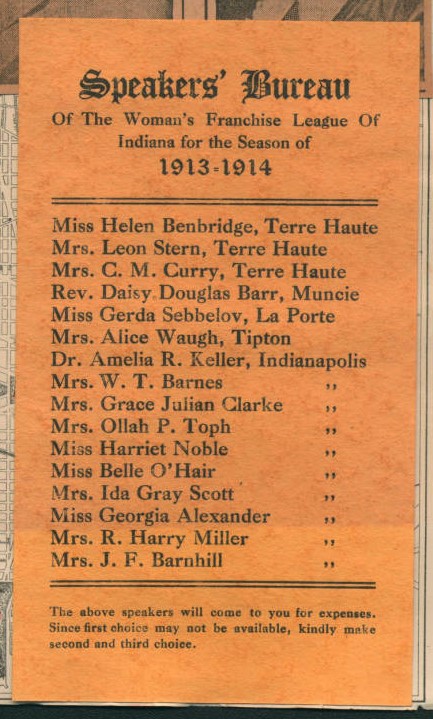

In 1911, Stern and her husband moved to Terre Haute, but the move did not prevent Stern from engaging in women’s rights work at a state level. Instead, she increased her influence through the Indiana General Federation of Clubs and the Women’s Franchise League (WFL) over the next several years. She also served as an officer of the Terre Haute section of the National Council of Jewish Women and as the group’s representative to the other statewide women’s organizations. By 1912, Stern was one of several directors of the WFL and spoke on the organization’s behalf around the state, often joining other prominent suffragists. Stern also served as the treasurer of the Indiana Federation of Clubs, an important position for an outspoken suffragist.

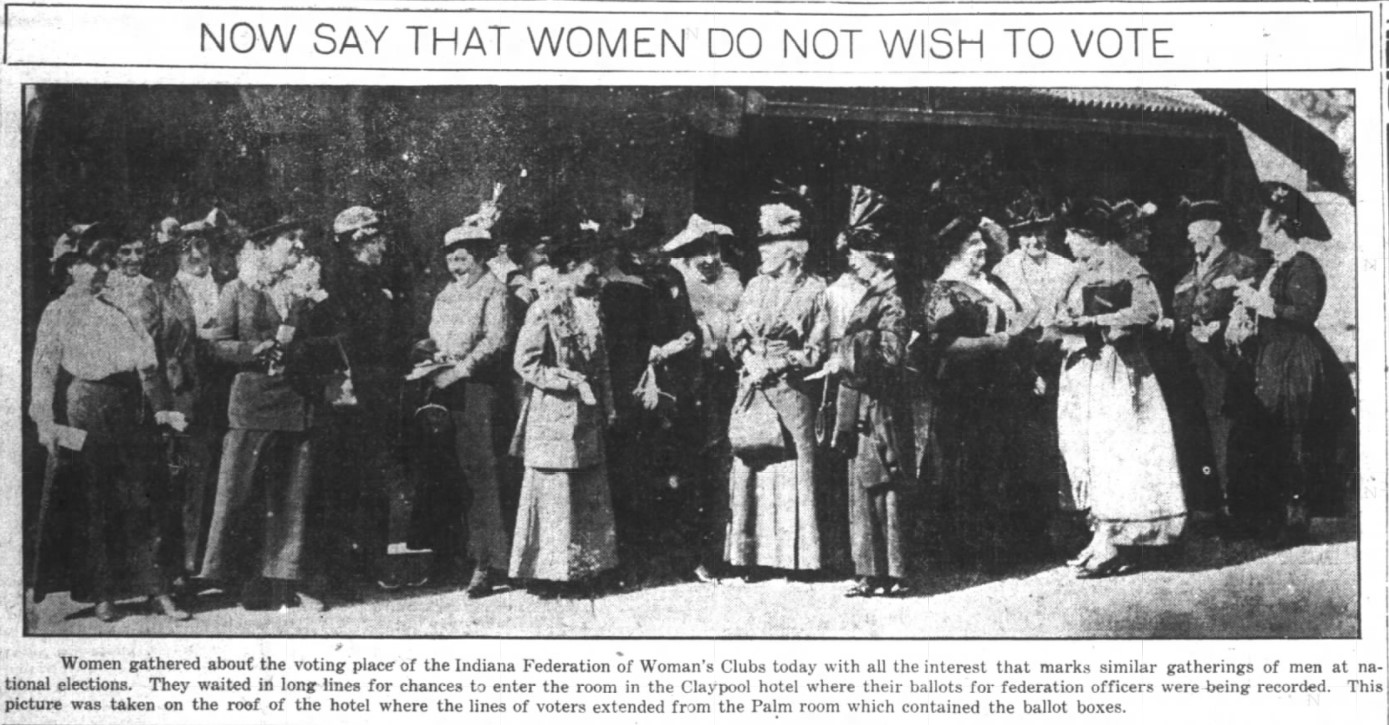

The large and influential Federation, which was an umbrella organization for a myriad of women’s clubs, had not yet taken a stance on the suffrage issue. Stern and other suffragists who held leadership positions were able to educate their colleagues and advocate for the vote from inside the organization. For example, in October 1912, when the Federation of Clubs held their annual meeting in Fort Wayne, the WFL held a “suffrage luncheon” at the same hotel as the meeting, providing an opportunity for Federation members to learn about issues surrounding the vote. Clarke and Stern both gave toasts. Clarke’s speech was a straightforward one about lessons from her recent work campaigning for suffrage. Stern responded in jest with a mock anti-suffrage toast titled “I Do Not Need the Vote,” intended to show the absurdity of the opposition’s position, especially when that position was assumed by a woman who would only benefit from increased civic rights.

In her work with the Indiana Federation of Clubs, Stern faced subtle but powerful antisemitism. Suffragists and club leaders were shrewd politicians. They had formed lobbying groups, penned legislation introduced in the Indiana General Assembly, changed the minds of important leaders such as Governor Ralston, and largely tipped the scales of public opinion towards enfranchisement. As with male politicians, the women’s politics sometimes got ugly. While disparaging comments and mudslinging was considered a regular part of campaigning for men, when women engaged in the same traditional, if “unseemly,” tactics, they were labelled as “catty.” The infighting surrounding the 1915 campaign for the Indiana General Federation of Women’s Clubs presidency was brutal, not because the women were especially petty, but because they were political actors vying for power in a large, influential organization. Despite her best efforts, even Stern was drawn into the fray. Notably, some of the damage inflicted on her character seems to be the result of latent antisemitism in some of her colleagues rather than any action or position that she took herself.

As Terre Haute clubwomen Lenore Hanna Cox and Stella Stimson clashed in the fight for the Federation, Grace Julian Clarke was often in the middle of the battle and was the recipient of many letters showing support for or opposition to the candidates. Clarke supported Cox for the presidency and worked hard to back her candidacy and oppose Stimson. Clarke’s main complaint about Stimson was that she felt Stimson’s temperance work interfered with her suffrage advocacy, potentially driving away supporters who did not support Prohibition.

In August, for reasons unknown, Stimson wrote Clarke suggesting Stern as Federation president. Since Stimson herself was vying for the office, this seems to be some sort of political chess move – perhaps positioning herself as uninterested in order not to seem overly ambitious. Stimson’s letter had a negative impact on Stern’s reputation amongst her Federation colleagues. It made Clarke worry that Stern was another potential obstacle to Cox’s presidency. As word got out, some Federation members suspected Stern to be Stimson’s “spy” at closed meetings and wanted to exclude Stern from the Federation and the Terre Haute WFL. Unfortunately, some of this suspicion seems to have been tinged with antisemitism.

Stern was never interested in the Federation presidency. In fact, she told a colleague that she “absolutely would not have it if it were handed to her on a platter.” Her résumé shows that she was more interested in philanthropy and women’s rights than club politics. And yet, Cox and another Terre Haute clubwoman, Helen C. Benbridge, attacked Stern in letters to Clarke. Benbridge wrote an especially hateful letter.

Stimson’s tactic for beating Cox was to paint the latter as less “Christian,” by which Stimson meant less moral, because Stimson was a prohibitionist while Cox did not believe the liquor issue was as important as the vote. While campaigning, Stimson claimed that Cox was not Christian. Benbridge took this as an opportunity to attack Stern, bending Stimson’s words back to a more literal interpretation of what it meant to be Christian. Benbridge wrote, “If Mrs. S[timson] objects to Mrs. C[ox] because she is not a Christian why does Mrs. Stern strike her as a good candidate?” While Benbridge was certainly being somewhat sarcastic, the implication was that being Jewish should disqualify Stern from the presidency. It has just a hint of antisemitism, especially as Benbridge continued to write in a disparaging way about Stern’s influence in the Jewish community of Terre Haute.

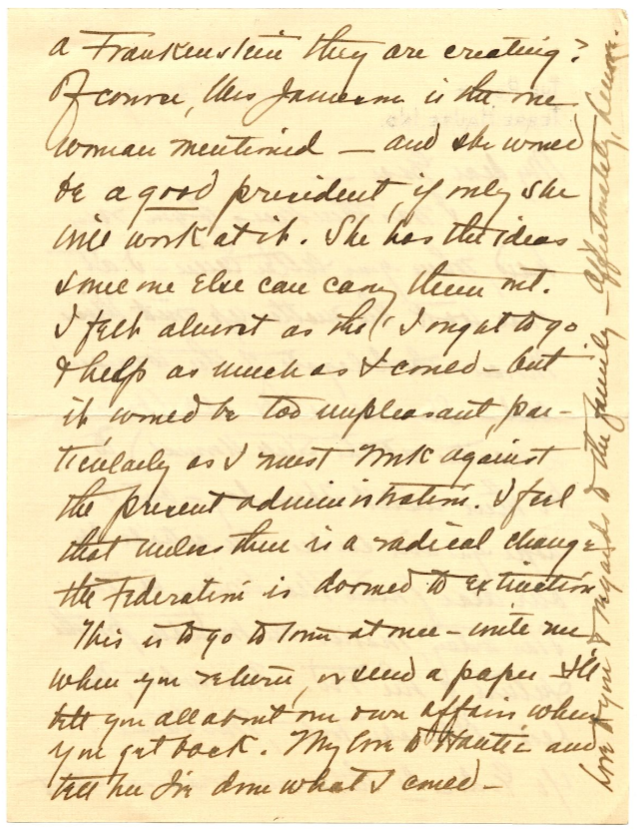

Benbridge claimed that Stern was “furious” with Stimson “about several Jewish matters.” Stimson was a Christian and an active leader of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, so why she was involved in “Jewish matters” to the extent that she could anger Stern, a prominent Jewish leader, is unclear. Cox also wrote disparagingly about Stern, encouraging the baseless rumor that Stern was Stimson’s spy and pushing to remove her from the WFL and Federation. Cox wrote that by including Stern in the Federation leadership, they would be creating “a Frankenstein” of an organization. This dehumanizing language is also telling of Cox’s potential antisemitic feelings toward Stern.

In another letter disparaging Stern and seeking Clarke’s support to remove Stern from the Terre Haute branches of the Federation and WFL, Cox claimed that she (Cox) had the support of the National Council of Jewish Women, not Stern. This was unlikely considering Stern was an officer of the Terre Haute Section of the Council while Cox was a Christian who attended an Episcopal church and thus not a Council member. However, the claim does show the necessity of securing the support of an active community of Jewish women and perhaps the threat Cox felt Stern might pose to her leadership in Terre Haute. Cox did have to admit to Clarke that Stern had graciously supported a motion that Cox had made during a recent meeting. Cox, who appeared to view things in black and white—allies and opponents—could not understand why Stern, whom she had labelled as her enemy, could possibly agree with her on an issue. Cox asked Clarke, “Is she really normal?” Again, using “othering” language that divested Stern of some humanity.

It is worth noting that while Clarke worried about Stern’s connection to Stimson in her private letters, Clarke did not descend into name calling like the others. Clarke often spoke positively of Stern in public, praising Stern’s philanthropic work and calling her “able and efficient in whatever she undertakes.” Clarke and Stern worked together successfully for many more years.

That any of these attacks were aimed more harshly at Stern because she was Jewish is, to some degree, speculation. Again, this was politics, and mudslinging was always part of the game. However, we can be certain that Stern did face antisemitism at various points in her career. According to historian Melissa R. Klapper, Jewish women had only recently, and only tepidly at that, been included in the suffrage movement. Meetings, resolutions, songs, and speeches were imbued with Christian rhetoric that could make Jewish women feel excluded. Rallies and conventions were often held on Friday evenings when observant Jewish women would have been prevented from attending or felt conflicted about participating. Some Jewish women were reluctant to work with Christian suffragists who used contact with Jews as an evangelizing opportunity.

The antisemitism imbued in the women’s suffrage movement was perhaps most clearly expressed through its leadership. Nationally prominent suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton published an article referring to Jews as “a useless portion of society.” In her Woman’s Bible, Stanton went on to blame the “backward” ideas espoused by Judaism for women’s second-class status. Famed Methodist minister and suffrage orator Anna Howard Shaw blamed Jewish immigrants for failed suffrage campaigns and Quaker suffragist Alice Paul worked amicably with Jewish women in public, while privately expressing her “antagonism for Jews.” According to Klapper, the antisemitism of their colleagues meant that Jewish women felt an “unease with their place” and “occupied an ambiguous position” within the larger suffrage movement. So whether or not we interpret the hostility directed toward Stern by her fellow clubwomen as antisemitic, Stern would certainly have been familiar with the writings of the leaders of the women’s movements and received the message that she was an outsider in a Christian space.

We also know Stern faced antisemitism because she wrote about it in her own words. In 1911, Stern published her poem “The Greater Creed” in The Butterfly, a magazine concerned with Progressive Era reform, politics, and culture. Stern’s poem had three main points. First, she expressed the completeness Jews felt in worshipping one God, explaining to a Christian reader that Jews did not feel the need for “a mediator.” While this may seem like a dig at the complexity of Christian spiritual practices, her goal was not to be divisive. She paid respect to the equality of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, noting that they were God’s children. Her second goal in “The Greater Creed,” was to argue that while some people worshipped Allah, some Christ, and some “Reason,” one’s chosen belief system mattered less than one’s actions. She stated that it was work on behalf of one’s fellow man, not creeds, that made one holy. She wrote, “Fling afar your doctrine. Cast aside your fears.” Her final and most powerful message was that all people of faith should unite to serve those in need. She concluded:

Seek out the weeping ones and dry their tears.

The sick, the halt, the sinner and the blind,

Oh, pity them and love them and be kind.

For after all, the helpful human deed

By Christian, Turk or Jew to one in need

Can bring more souls to God than all man’s creed.

While Stern pushed back against the dominance of Christian culture at the start of the poem, she immediately moved on to her main point: doctrine doesn’t matter as much as serving the poor.

But by 1917, Stern had extensively revised this poem, doubling the stanzas, and drastically changing its tone. While she closed the poem, renamed “The Jew to the Gentile,” with the same eighteen lines that made up “The Greater Creed,” she added thirty additional lines to the beginning. In these new stanzas she boldly confronted the antisemitism she faced in the world around her. First, she addressed the condemnation she felt Christians delivered to Jews for not believing in the divinity of Jesus. Quoting a fictional priest, she wrote:

The priest bent angry gaze upon the Jew,

“What base ingratitude. Shame, shame that you

Who love the Father, should deny His Son.

Christ, Jesus, is Divine, with God is one.”

Still speaking in the voice of the judgmental priest character, she continued on the same theme: “Oh, stiff-necked race/ Forever shall the glory of God’s face / Be turned from you.” She then shifted her focus to what she perceived as a hypocritical characteristic of Christianity, that is, violently persecuting those who did not share Christian beliefs. She wrote from the perspective of a Jew responding to the condemnation of the fictional priest, stating that Christianity had forced belief in the divinity of Christ on the world “with rack and sword.” Again, after her attack, she softened her tone and in her next few lines, she explored the theme of Jewish forgiveness. She wrote:

And yet

Although you maimed us with the scourge and flame

And tortured and reviled us ‘in His name’;

We reach out arms in friendliness to you

And plead for peace.

After this stanza, Stern then repeated the lines of the 1911 version of the poem, which were focused on the importance of acting on behalf of the poor and needy as opposed to arguing over religious creed. So, what had changed between the uplifting lines of the 1911 work and the castigating revision of 1917? We can surmise that she came into greater contact and conflict with antisemitic language or ideas, likely in the context of the women’s organizations that occupied most of her time.

Despite the opposition of members of the Federation or any other potential antisemitic incidents she may have faced, Stern rose above the political backstabbing and continued to serve as a leader within the Federation. She also became the treasurer of the National Council of Jewish women (the nationwide organization, not just the Terre Haute section). She even found time to lead a local Vigo County organization dedicated to studying and protecting birds. As the suffrage movement headed into its final stretch, Stern made an important contribution to the final push for the vote through the Legislative Council of Indiana Women, a statewide organization dedicated to lobbying the General Assembly.

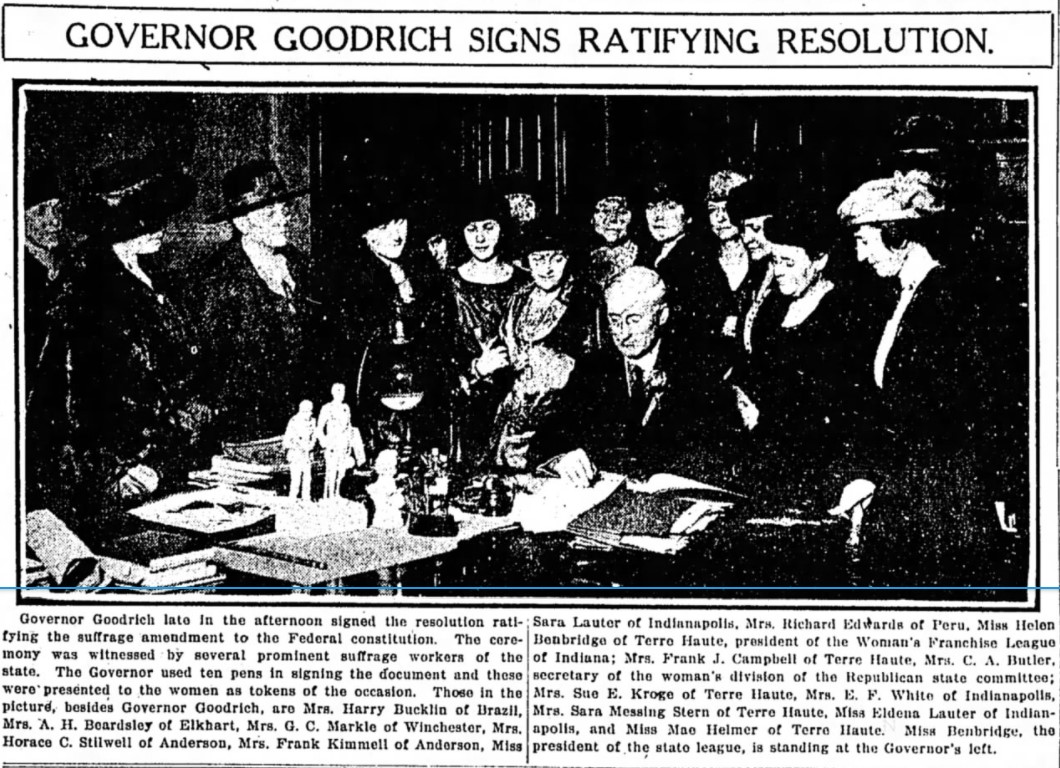

On January 16, 1920, Indiana ratified the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Sara Messing Stern was among the “women who saw the culmination of a struggle in which they were pioneers,” according to the Indianapolis News. The following day, Governor Goodrich signed the ratification resolution surrounded by the “prominent suffrage workers of the state.” A photograph on the front page of the Indianapolis Star, shows Stern among them, looking on approvingly. As she stood in the governor’s office, she saw her life’s work for women’s suffrage achieved.

Stern was only one of a large army of women fighting for full citizenship rights for women, yet she made an impact on Indiana history. She felt called to serve God by caring for those less fortunate, and she left a legacy of improving her communities in Indianapolis and Terre Haute. She overcame many obstacles, including the inherent antisemitism of Progressive Era women’s movements. Throughout her career, Sara Messing Stern maintained her Jewish faith and pushed back against antisemitism of her colleagues, powerfully expressing her defiance through her poetry. To Stern, the “Greater Creed” was not a specific religious doctrine, but instead helping others and striving for equality.

Notes:

For an extended and annotated version of this post, click here.

For an overview of the Federation controversy, read historian Jackie Swihart’s post: “A Petty Affair: Grace Julian Clarke and the 1915 Campaign for the Indiana General Federation of Women’s Clubs Presidency.”

View Grace Julian Clarke’s 1915 correspondence via the Indiana State Library Digital Collections.

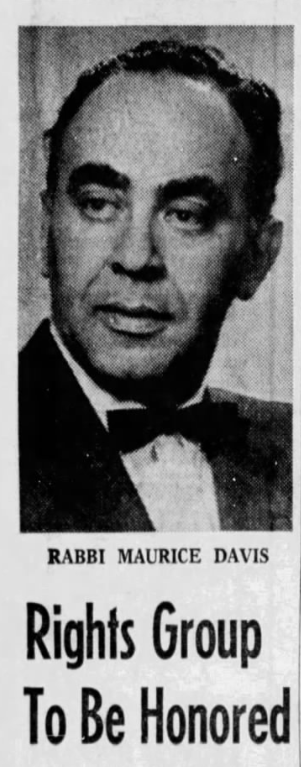

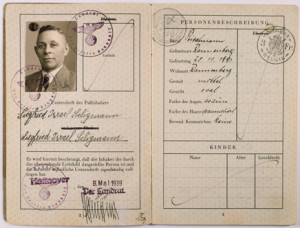

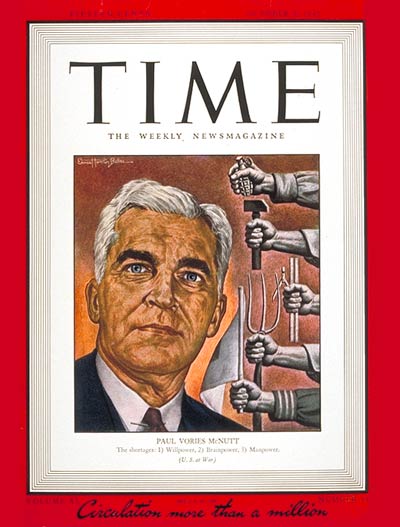

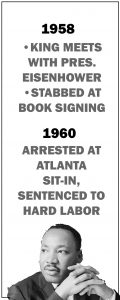

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

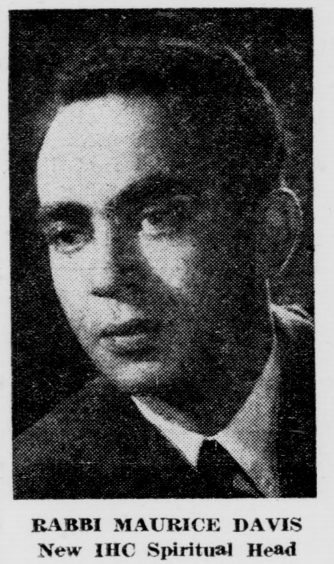

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

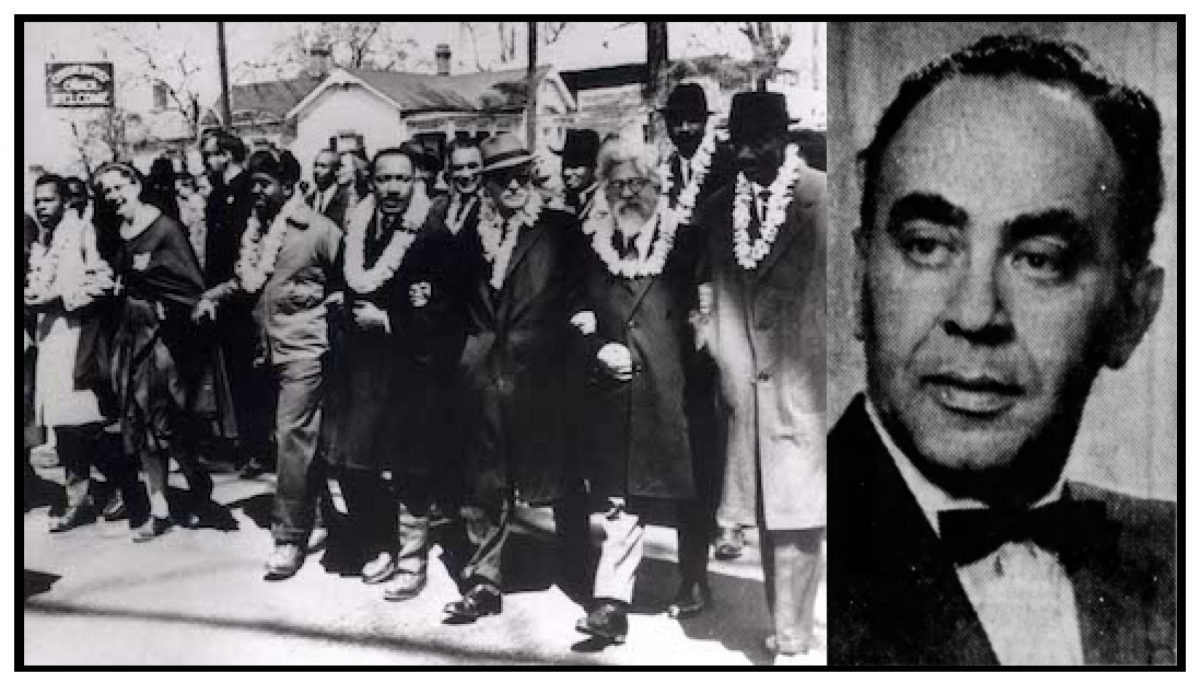

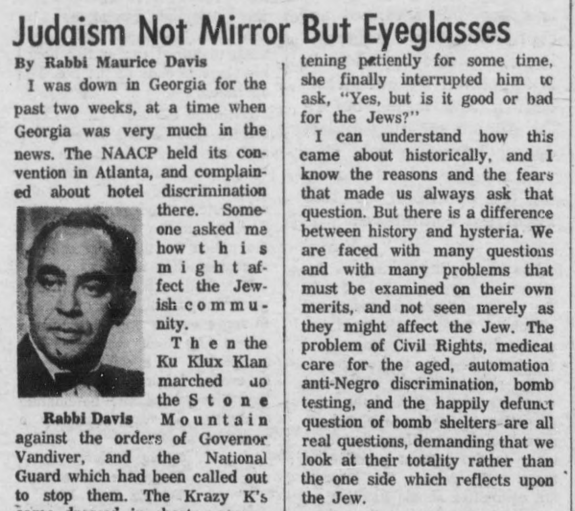

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

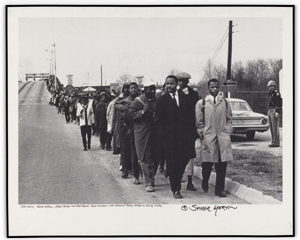

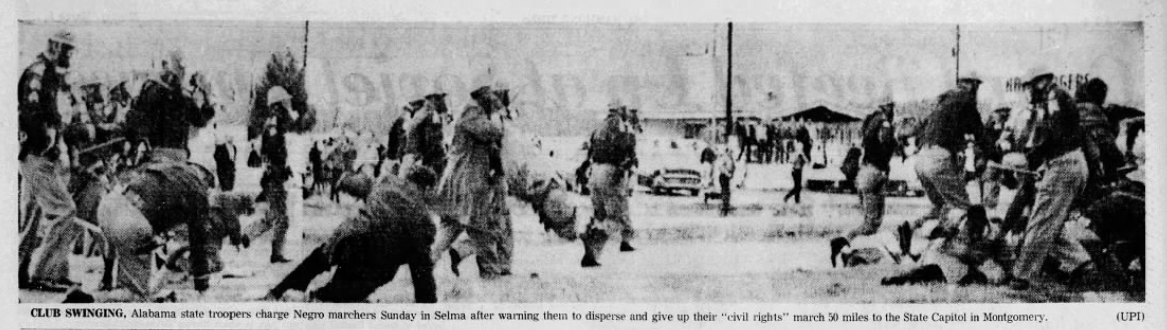

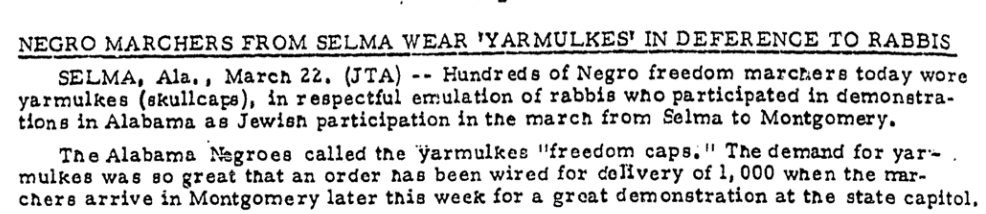

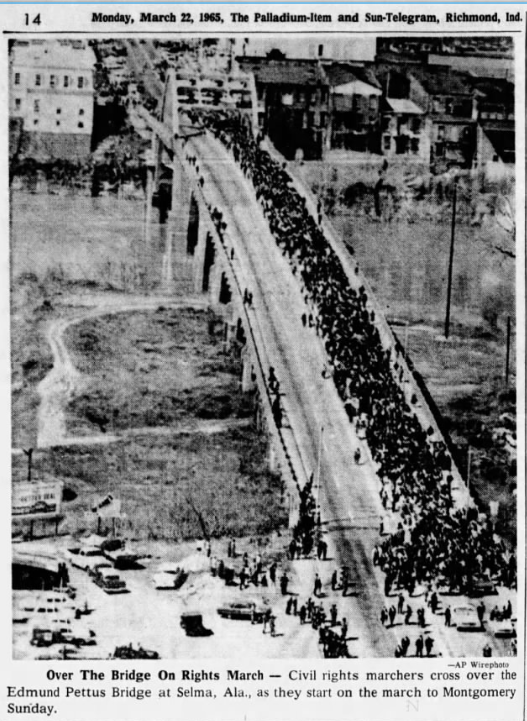

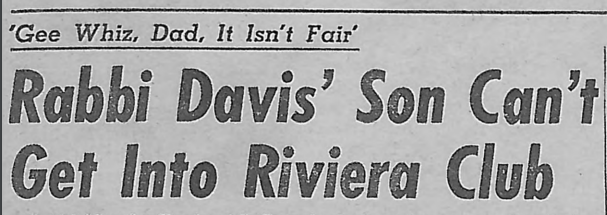

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he