In 1942, headlines in Indiana newspapers warned:

“Acute Labor Shortage Perils Midwest Farms”

–(Valparaiso) Vidette-Messenger of Porter County

but also

“No Labor Shortage”

– Indianapolis Recorder

So which was it? An acute labor shortage endangering the farms of the corn-belt, and in turn, the country’s war production? Or no labor shortage at all? The answer is surprising and continues to impact policy today.

The Agricultural Front

Just before U. S. entry into the Second World War, large farming and agricultural processing companies—which had become dependent on the cheap labor that was abundant during the Great Depression—warned of an impending labor shortage. They claimed that there was not a sufficient number of workers available to fill the positions left behind by the men enlisting in the armed forces, or by the men and women who left the farm for war-related industrial work.

At the same time, with the introduction of President Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease program (which lent food and supplies to Great Britain and its allies), the U.S. needed to produce more agricultural products than ever before. The battle on the agricultural front would need a larger number of agrarian soldiers. Indiana newspapers worried over how Hoosier farmers would meet production goals as their sons left for the “army camps” and “defense industrial plants.” The Muncie Post Democrat continued:

Now that the sons are gone, the farm operators find it impossible to compete with industrial labor wages for help. This may result in many acres uncultivated this season . . . This condition rates as serious when food production is important in the defense program.

In spring 1942, Purdue University reported that “anticipated shortages of farm labor, resulting from enlistments in the armed forces and attractive industrial wages, have not developed.” However, as the year went on, Indiana newspapers became more frantic in tone. They reported that farmers were selling acreage and animals because they could not find farm hands to help with the work. The weekly industry newspaper, the Prairie Farmer, surveyed eighty-one midwestern counties and reported that three-fourths of them “were found to be suffering from a shortage of farm hands.”

Indiana Canneries and the “Labor Shortage”

By the fall of 1942, large Indiana agricultural businesses joined the national cry of “labor shortage.” Indiana newspapers gave extensive coverage to the professed concerns of the tomato canning industry. The Muncie Evening Press ran the headline: “Labor Shortage Hits Tomatoes: Cannery Shutdowns and Crop Losses Threaten.”

The article reported that the “acute war-born labor shortage” would close a dozen canneries and that “picked tomatoes awaiting processing [were] lying idle and periled by rotting.” State government officials and the Indiana Farm Bureau spoke on behalf of the canneries and appealed to local men and women to go to work at the plants. Hasil E. Schenck, president of the Indiana Farm Bureau, stated:

Reduced farm production will be no reflection on the patriotism of farmers, for without manpower they can not produce food and fiber any better than industry can produce ships, tanks and guns without steel.

Indiana Governor Henry Schricker issued “an appeal to housewives and all others available to apply for work at the nearest cannery.” The Evening Press reported that the canneries were already employing WPA workers and were calling for women “peelers” and for school children “packers” to volunteer their services.

Yes, volunteer. These industry giants, many of whom had profitable government contracts, were asking for women and children to freely donate their labor. A few days after the call for volunteers went out, the Elwood Call-Leader praised the response of school staff and students in the Madison County area while rebuking the “apathetic and uncooperative” attitudes of local women—women who likely had increased workloads at home because of the war effort. According to the article, employment service and local government officials complained that “despite all appeals that have been made throughout the past week, many . . . women still do not realize the seriousness of the situation and are not willing to work, even [though] they are needed only to get through the brief critical period the industry is now facing.”

The Call-Leader added that army officials were “alarmed at the situation” and were “making a check to see whether the army will be able to get the tomatoes it has ordered.” The canneries’ message was clear. Without cheap or free labor, American boys on the front would go without food. Like corporations across the country, Indiana businesses began to demand that the government supply them with an inexpensive source of labor.

African American Newspapers and the “Labor Shortage”

And yet, African American newspapers saw “no labor shortage.” The Indianapolis Recorder reported that the companies need only to “hire negroes.” The Recorder, continued:

Nobody has yet proved there is a labor shortage in this country. . . There is no need to work a few workers to death while others walk the streets hungry, seeking work. There are still enough qualified workers in this country to allow employers to continue their discrimination against workers because of the race, religion, and nationality of such workers.

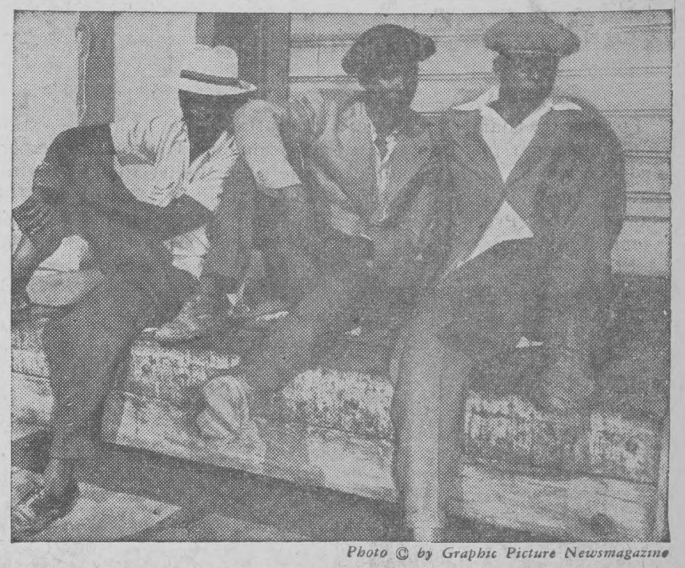

Indiana’s African American newspapers reported that thousands of African Americans were looking for work and were willing to travel great distances to take jobs, but employers didn’t want them. For example, in November 1942, the Indianapolis Recorder and the Evansville Argus reprinted a report from Graphic Magazine that 3,000 African American men left “the Deep South” at the request of California farmers for help saving the harvest. When they arrived “there were no jobs for them!”

The Labor Shortage Myth

The observations of the African American newspapers were correct. There was no labor shortage that the federal government could not meet with domestic workers. However, the myth of the labor shortage had its own power.

Over the previous decade, the Great Depression created a large surplus of workers seeking employment. In 1941, the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Labor reported that farmers had “come to consider this over supply as the normal supply, and to consider any reduction in the surplus supply as a shortage.” These departments concluded, however, that all of the shortages, perceived or real, could be met by moving surplus domestic workers into the areas of need. The catch, however, was that the balanced supply of available workers and demand for their labor required employers to pay a fair wage for agricultural labor.

A remarkably organized effort of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and the U. S. Employment Service (USES) was prepared to deal with any real “pockets of labor scarcity.” They expanded the New Deal migratory camp program, setting up permanent and mobile camps around the country to bring American workers across the country for harvests. However, because employers had to pay more reasonable wages, they still complained of shortage. In fact, they cited higher wages as evidence of a shortage.

Statistics from the Indiana division of the U.S. Employment Service show that Indiana’s available labor pool reflected the national situation. J. Bradley Haight, the Director of the U.S. Employment Service (USES) in Indiana estimated in 1942 that there were “100,000 individuals in the state seeking employment. He stated, “The job insurance division issued checks to 40,000 persons. This represents a reservoir of labor which is to be tapped.” However, the large growers, dependent on cheap labor, continued to cry shortage even as they were provided with workers by the FSA and USES—workers that they didn’t want to employ because of racial prejudice or unwillingness to pay a fair wage.

So these wealthy, powerful, and organized growers and processors of agricultural commodities demanded that the federal government respond to their manufactured labor shortage by importing foreign workers. The government quickly gave in to their demands. History professor Cindy Hahamovitch, writing for the Center for Immigration Studies, summarized the government’s response to the labor myth:

The officials who created the guestworker program never believed there was a national labor shortage in agriculture. . . They created the importation program, not because it was necessary, but because it was politically expedient to do so, because the nation’s most powerful growers were demanding the preservation of the cheap, plentiful, and complacent labor force to which they had become accustomed over the previous 20 years of agricultural depression.

The federal government complied because the myth was persuasive. A false labor shortage would have the same effect on agricultural production as a real one. No amount of statistics or economic reports could allay the fears of farmers worrying if sufficient help would be available at harvest time. Therefore, farmers anticipating a lack of aid and picturing their produce rotting in the fields, would plant less, and the country wouldn’t meet its production goals—just as if there was a real labor shortage.

Despite their best efforts to meet the real pocket labor shortages with domestic workers and their distribution of reports on the available domestic labor pool, the federal government needed to allay the small farmer’s growing fear of a massive shortage. By 1942, the Roosevelt administration was cornered into responding to the shortage myth by importing foreign workers. As Congress tore apart the Farm Security Administration and its program of migrating workers to areas of need, U. S. Secretary of Agriculture, Claude R. Wickard, left for Mexico to negotiate a deal that would affect agricultural and immigration policy for decades.

Hoosier Dirt Farmer as U. S. Secretary of Agriculture

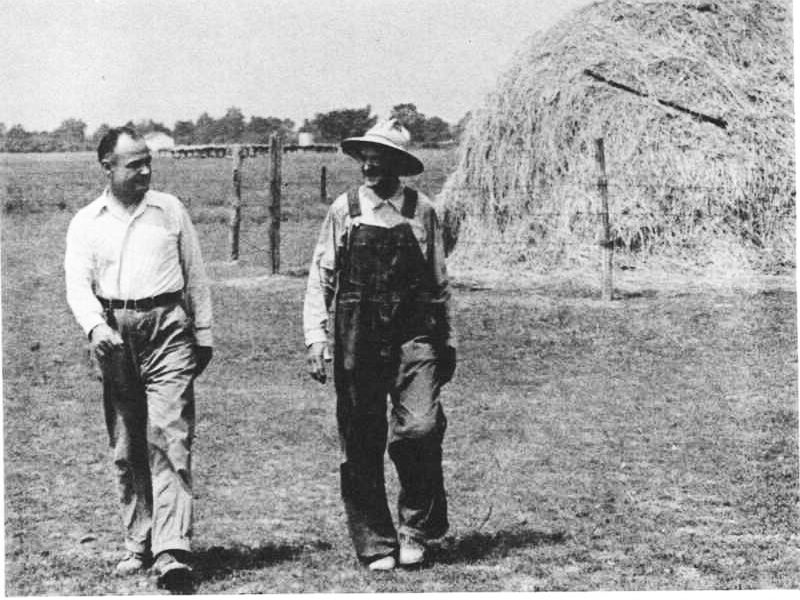

Claude R. Wickard was a Hoosier dirt farmer through and through. He was born in 1893 and raised in Carroll County on his family’s farm. His father, a staunch democrat named for Andrew Jackson, was a strict disciplinarian who raised his son with every expectation that the farm was his present, future, and legacy. The younger Wickard, however, grew ambitious. He saw that the farm could be more productive and efficient with the application of modern methods. Against his father’s wishes, he enrolled in classes at Purdue, where he learned about scientific farming and got hands-on experience with sanitary hog care and breeding. He soon vastly improved the farm and received recognition from farming organizations as a leader in modern farming methods. His influence in local Farm Bureau organizations grew in the 1920s and he advanced to several leadership positions where he took on the challenges of his fellow farmers.

By 1930, several factors made Wickard a prime political candidate. First and foremost, while most Indiana farmers were Republicans, Wickard was born into a staunchly Democratic family and remained loyal to the party despite the fact that the national party had not prioritized rural concerns through the 1920s. Thus, Wickard was one of the few farmers with influence in the Farm Bureau and other organizations who was also a Democrat. Second, Wickard’s embrace of scientific farming ideas made him open to production control as a method to achieving parity for farmers. Most farmers, who were already barely making ends meet while operating their farms at full production could not imagine cutting down on output. Wickard, however, could see that farmers needed help from the federal government to make the drastic, nationwide economic shift required to give them the same standard of living as the urban people they fed. This way of thinking aligned with the ideas of the men who would soon take over leadership of the nation. Wickard was poised to join them.

His political career began modestly. A group of county organizers convinced him to run for a state senate seat and he reluctantly agreed. Wickard stated in an interview:

I didn’t like politics . . . [but] like all other things, sometimes you’ve got to make your contributions to your community and to the Democratic Party . . . I had a feeling of responsibility toward my fellow citizen.

Wickard was elected state senator November 8, 1932 as Democrats swept elections across the country and Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the U. S. presidency.

In May 1933, the Agricultural Adjustment Act took effect and farmers saw that the new administration recognized their plight. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA or Triple-A), a division of the Department of Agriculture, was tasked with creating parity through taxing companies that used agricultural produce and decreasing production. Wickard was quickly elected chairman of the Corn-Hog Section of the Indiana Triple-A. He soon became the Assistant to the Chief of the National Corn-Hog Division, and in July 1933 Wickard went to Washington.

When he arrived in Washington as second in command of the Corn-Hog Section of the AAA, he was overwhelmed by the job. In his own words, Wickard was “just a farmer” and had to work to understand the complex economic issues the administration faced. And he got frustrated with the pace of bureaucracy. However, he was likeable, earnest, easy to work with, and his ideas about parity aligned with those of Henry Wallace, the Secretary of Agriculture. Most important to Wickard’s rise, however, was that he was known as a loyal Democrat and commanded the respect of midwestern farmers.

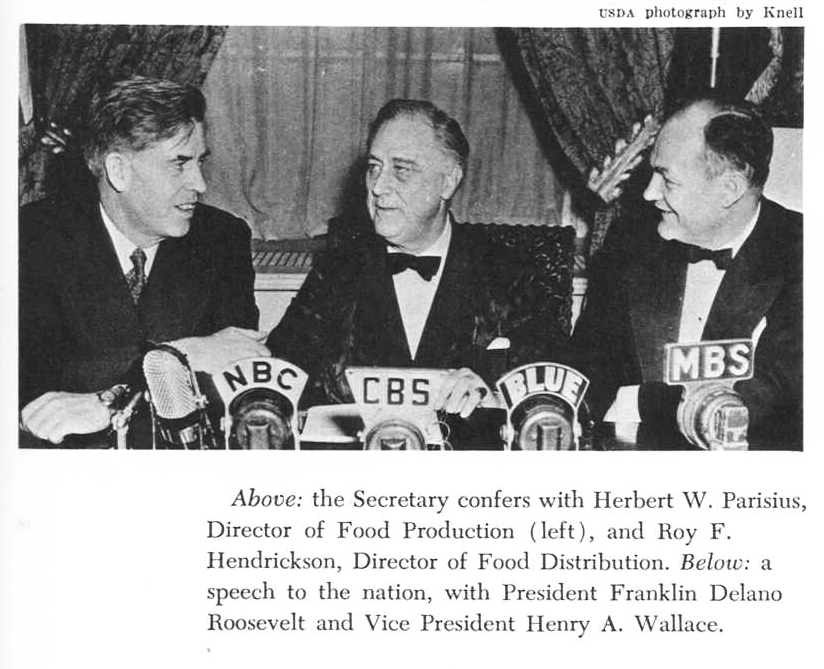

When the Department of Agriculture reorganized by region, as opposed to commodity in 1936, Wickard became Assistant Director of the North Central Division. By this point, Wickard was on Wallace’s radar and the secretary saw potential in the Hoosier dirt farmer. Wallace later noted that Wickard was rare in a department of apolitical technocrats and subject experts in that he was actually a Democrat. Wallace stated: “He was about the only one of the whole crowd in agriculture that had any claim to being a democratic politico.” In the fall of 1936, Wallace brought Wickard with him as he stumped for FDR throughout the Midwest. When FDR won reelection, Wickard continued to make himself useful to Wallace at the USDA and was quite successful and well-liked in his division.

In January 1940, Wallace recommended Wickard to FDR for the position of Undersecretaty of Agriculture. After making sure he was not aligned with Roosevelt’s Hoosier adversary Paul McNutt, the president agreed. Wickard was sworn in February 29, 1940. He served less than six months before Wallace resigned as Secretary of Agriculture to run as FDR’s vice president. Wallace recommended Wickard to succeed him and Wickard was sworn in as the U. S. Secretary of Agriculture September 1940.

Wickard, The Labor Issue, and The Bracero Program

With much of Europe dependent on U.S. agricultural production, the Secretary of Agriculture’s job was even more important than in peace time. Meeting war production goals was paramount. Wickard faced many challenges, among them, the increasing claims of a labor shortage. In December 1941, Wickard testified before the U.S. House of Representatives Agriculture Committee:

The farm labor shortage is not as serious as generally believed. Farm production has suffered, of course, from the loss of farm hands who have been drafted or got higher pay in defense plants. But the situation is not alarming.

While he downplayed the labor shortage claims, he did make it clear that farmers would “have to pay more for their help” than they had before the war stimulated the economy and reduced the labor surplus. As the earlier examination of newspaper articles has shown, this was not an option many corporations were willing to consider.

Less than a year later, Wickard had changed his approach to the issue. The (Richmond) Palladium-Item reported :

Secretary of Agriculture Wickard warned that the United States would face a food shortage unless it quickly solves the problem of manning the farms. He estimated the armed forces and factories may drain off approximately 2,000,000 farm workers by the end of 1942 in addition to those who have already gone.

By this point, it seemed like Wickard was treating the labor shortage claims as a legitimate threat to production goals. However, this same Palladium article still noted that “the most mentioned causes” of the shortage “were high wages.” Even at the peak of industry claims of a labor shortage, the crux of the issue was still that companies would “have to pay more for their help,” as Wickard told the House in 1941.

Tasked with addressing the issue, Wickard left for the Second Inter-American Conference on Agriculture in Mexico City early in July 1942, to make a deal that would import Mexican workers and ensure the United States met its production goals. Several agencies were involved in creating a plan to import Mexican agricultural workers, but it was Wickard who was responsible for negotiating an agreement between the interests of the Mexican government, the United States government, American farmers, labor organizations, and large farming and processing conglomerates.

Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs Evequiel Padilla Peñaloza was reluctant to agree because of U.S. exploitation of and discrimination against Mexican workers in the past. Padilla insisted that any agreement include a number of guarantees for the rights of braceros. Padilla demanded Mexican workers receive the same guarantees of wages and working and living conditions as American workers. Wickard agreed to a minimum wage and work and living standard. However, there were no such guarantees for American workers. Thus, as labor organizations were quick to point out, these workers were guaranteed, at least in theory, more protection by the U. S. government than domestic farm laborers. After ten days of negotiations Wickard formalized the agreement August 4, 1942. In less than a year’s time, Indiana farms were benefiting from foreign labor. Hoosier response to these guest workers was mixed.

In Part Two of this post we will look at the stories of these farmers and foreign workers as told through Indiana newspapers:

Further Reading:

Albertson, Dean. Roosevelt’s Farmer: Claude R. Wickard in the New Deal. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

Bracero History Archive. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Brown University, and the Institute of Oral History at the University of Texas El Paso, http://braceroarchive.org/

Collingham, Lizzie. The Taste of War: World War II and the Battle for Food. New York: Penguin Books, 2011.

Claude R. Wickard. State Historical Marker. Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/markers/4420.htm

Craig, Richard B. The Bracero Program: Interest Groups and Foreign Policy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971.

Hahamovitch, Cindy .”The Politics of Labor Scarcity: Expediency and the Birth of the Agricultural ‘Guestworkers’ Program,” Report for the Center for Immigration Studies, December 1, 1999, accessed https//cis.org/Report/Politics-Labor-Scarcity.

Hurt, Douglas R. American Agriculture: A Brief History. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1994.