John Whistler came to America as a British soldier in the Revolution, under the command of General John Burgoyne. He was captured, paroled, and sent back to England. His elopement with Anna Bishop, daughter of Sir Edward Bishop, a close friend of his father, brought the young man and woman to America where they made their first home at Hagerstown, Maryland, in 1790.

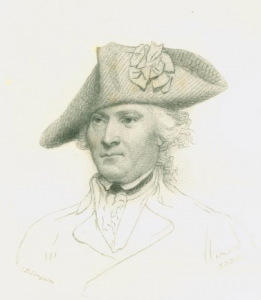

Major General Arthur St. Clair and Chief Little Turtle, image

courtesy of Army.mil.

The following year, John Whistler joined the army of the United States, which was fighting a confederation of Native American tribes over control of the Northwest Territory. John Whistler traveled west with Governor of the Northwest Territory Major General St. Clair and his army. Opposing St. Clair was the native confederation army led by Chief Little Turtle, comprised of Miami, Shawnees, and Delaware. According to Thomas E. Buffenbarger, U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Chief Little Turtle:

led over 1,000 warriors of the native confederacy in attacks on the separate camps. The 270 Soldiers from the militia’s camp fled quickly, giving little resistance to the attack, and leaving the main encampment of the inexperienced regulars of the 2nd Infantry Regiment to fend for themselves. The artillery’s potential firepower was never utilized as artillerymen fell dead around their exposed cannons, cut down by Little Turtle’s warriors. The battalions of infantry formed up and commenced firing to defend against the encircling warriors. . . . As the casualties mounted and the cannons fell silent, the Army’s position became grave. After three hours of fighting, St. Clair ordered a retreat to Fort Jefferson.

Buffenbarger noted that over 900 soldiers and their families, were killed and left behind on both sides of the Wabash. Whistler escaped after suffering severe wounds received at the “Wabash slaughter field” handed to the Americans by Little Turtle’s warriors at Fort Recovery. Back in Cincinnati at Fort Washington, Whistler returned to receive a new assignment and was joined there by his wife.

General St. Clair was replaced by Revolutionary War hero “Mad” Anthony Wayne, to command an Army called the Legion of the United States. When General Wayne’s army arrived, Whistler joined them on the march into northwest Ohio where he participated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, which “was decisive in ending the Miami Campaign and helped establish the U.S. Army’s proud heritage of victory.”

After defeating the Indian confederation under the leadership of the Shawnee brave Blue Jacket, on August 20, 1794, Wayne moved his Legion up the Maumee River to the large American Indian settlement of Kekionga (now the City of Fort Wayne) at the confluence of the Three Rivers.

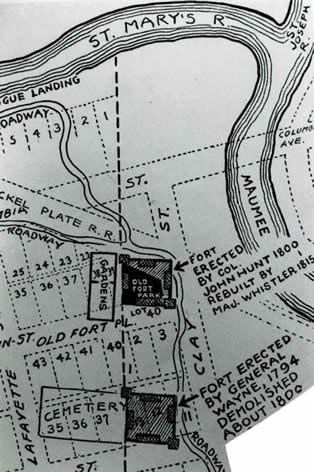

Wayne ordered a fort to be built in 1794 on the high ground overlooking the confluence of the Saint Mary’s and Saint Joseph rivers and the Miami town of Kekionga. In 1798, Colonel Thomas Hunt began construction of a second American fort at the Three Rivers. This fort, near present-day East Main and Clay streets, was completed in 1800, and served as a replacement for the first hastily built one erected nearby to the south by General Wayne.

The American forts at the Three Rivers came under attack only once during nearly a quarter-of-a-century while they guarded United States interests in the midst of Native American territory. In 1815, after having withstood a siege three years earlier, this stronghold was replaced, under the direction of now Major John Whistler. By 1816, Whistler (the Fort’s Commandant) was transferred to a new assignment in Saint Louis, Missouri. The fort Whistler had rebuilt during 1815 and 1816 was the last in the Three Rivers region and on April 19, 1819, was abandoned by the U. S. Army.

After the Battle of Fallen Timbers, John Whistler and his wife resided in the garrison at Fort Wayne, and here, in 1800, George Washington Whistler was born, one of fifteen children. George became “Whistler’s Father” the father of James Abbott McNeill Whistler whose renowned oil on canvas, “Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother,” is known to the world as “Whistler’s Mother.”