This year, the federal government undertook the all-encompassing task of completing the U.S. Census, a project instituted every ten years. The census is a national count of everyone living in the United States, providing policymakers with essential demographic information that they use to map congressional districts and allocate federal funds. However, the COVID-19 pandemic created difficulties for its completion, specifically in counting those who did not complete the census form by mail or online. As the New York Times reported earlier this year:

Already, a multi-day nationwide count of roughly a half-million homeless people has been put off. Processing of mailed-in census forms has slowed because the bureau shaved its staff at regional centers in Jeffersonville, Ind., and Tucson, Ariz. And social-distancing cuts in the bureau’s call center work force have slowed down responses to people who want to complete the census by phone or need other kinds of help.

These kinds of obstacles are not new to census-takers. In fact, a similar problem occurred in South Bend during the 1920 Census, where a small, but powerful Influenza epidemic stunted the city’s completion of the census.

In South Bend, the work of the 14th decennial census started on January 3, 1920, with seventy-one initial enumerators (census takers) tasked with counting the city’s population. Initially, weather proved a more formidable foe. “The enumerators were somewhat handicapped owing to the severe weather encountered on the first day,” the South Bend News-Times noted. Despite the weather slowing down progress, enumerators succeeded in getting citizens to cooperate and answer all their questions. Inspector for the local district, attorney Edwin H. Sommerer, anticipated a count of the city population in fifteen days and the rural population in thirty.

Within a few weeks, this task was complicated by an outbreak of Influenza, a lingering problem possibly stemming from the widespread Spanish Influenza epidemic a year prior. The city downplayed the outbreak’s potential to become another epidemic on January 16, when Dr. Emil G. Freyermuth, secretary of the city’s board of health, reported that no cases had been noted by physicians and that a chance of an epidemic was an “exaggeration,” as recounted in the News-Times. Freyermuth seemed to be contradicted by the South Bend News-Times itself, which published a notice in the January 17 edition that “the ranks of the [paper] carriers are sorely depleted at the present time on account of the mild form of influenza prevalent in the city.”

By January 20, the outbreak had worsened, leaving factories in South Bend short on labor as a result. Four were reported dead the next day, including a student at Notre Dame, and the illness reached epidemic proportions at local Army camps. Despite continued assurances about the mildness of this outbreak by Dr. Freyermuth, the situation worsened to such an extent that the Salvation Army volunteered to assist in combating it.

On January 26, the South Bend News-Times officially declared an epidemic, after 1,800 cases were reported around the city (250 at Notre Dame alone) and twenty-two deaths over the prior weekend. Dr. M. V. Ziegler of the State Board of Health confirmed these numbers, but Notre Dame physician, Dr. F. J. Powers, denied the high level of cases, “stating that the majority was afflicted with colds and la-grippe [another name for the flu].” Regardless of the disputes, the city reeled from the disease.

The epidemic devastated census-taking, incapacitating forty-five of the eighty-five-member staff and crippling those still healthy enough to continue. Census district chief Edwin H. Sommerer told the News-Times, “the enumerators working find it difficult to complete their task because of the sickness in the homes.” The News-Times doesn’t mention whether enumerators took any preventative precautions to avoid infection, other than just staying home. By contrast, mail carriers only experienced a loss of five workers during the outbreak, which was attributed to them being more acclimated to the intense winter weather.

By January 27, the epidemic began to subside, with only one death reported on the Monday after the weekend in which twenty-two people died. Employees in factories, stores, and offices also started returning to work. Even though this news was positive, the News-Times encouraged its readers to remain vigilant, noting “This marked decline does not mean, however, that all danger is past . . . the public is warned by the health department to exercise the greatest precaution in avoiding colds.”

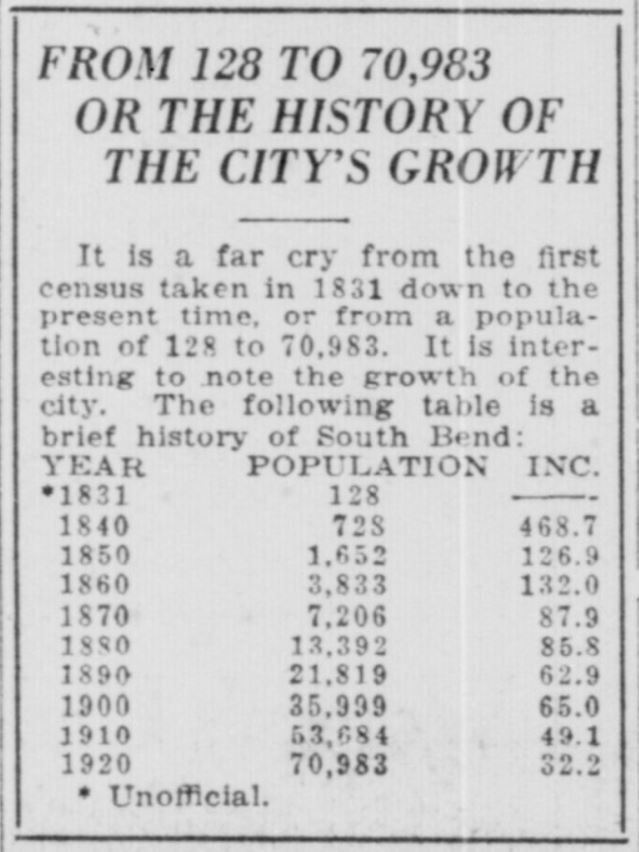

Despite delays, South Bend’s census enumeration continued, with some staff returning to duty starting on Wednesday, January 28 and over the subsequent days. By the end of January, the team completed half of the districts, most of which were cities, but still needed to complete the rural populations. On April 9, the News-Times reported that Sommerer and his team finished South Bend’s census, with only one-hundred names not accounted for. The city’s final count was sent to LaPorte for a larger district tabulation and then on to Washington, D.C. for inclusion in the federal count. In all, South Bend’s population increased by 32.2%, from 53,684 in the 1910 Census to 70,983 people in the 1920 Census. As the The city’s population increase “can be credited almost entirely to the industrial development of South Bend,” the News-Times wrote. Additionally, residents’ land valuation almost doubled, from $26,000,000 in 1910 to $43,000,000 in 1920. Months of bad weather, a flu outbreak, and some uncooperative citizens never stopped Sommerer and his crew of enumerators from obtaining the final figures and providing a demographic portrait of South Bend.

South Bend’s 1920 Census, and the flu outbreak that nearly derailed it, can inform modern census analysis. The COVID-19 pandemic has already affected the completion of the 2020 Census, with the deadline to to be counted extended to October 31. However, if Indiana’s enumerators are as dedicated to their roles as Sommerer’s team was 100 years ago, there is no doubt that an accurate count of our state will be completed.