In the early years of the AIDS crisis, when fear and misunderstanding accompanied any mention of the disease, schools across the nation faced a decision: whether to allow students diagnosed with AIDS to attend classes. In October 1985, a New York school district barred children from attending classes after officials learned that their mothers’ boyfriends had been diagnosed with the disease. When a different New York district admitted a student with AIDS around that same time, attendance dropped by 25%, despite the fact that the specific school the child was attending was kept confidential. In Swansea, Massachusetts, school officials decided to “do the right thing” by admitting a teenager living with AIDS—only two families decided to keep their children from school after the decision. A year earlier, in late 1984, a Dade County, Florida school admitted triplets who had been diagnosed with AIDS, but kept the siblings isolated from the rest of the students.

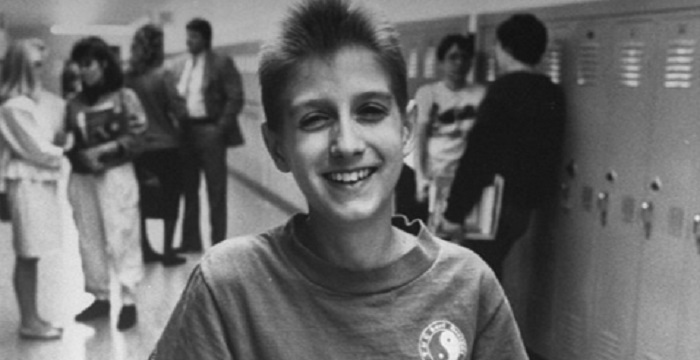

While new controversies sprung up around the nation, one school in Central Indiana shot to the forefront of the debate in the summer of 1985. Ryan White, a 7th grade student in Howard County, was diagnosed with AIDS in December 1984 after contracting the disease from a contaminated hemophilia treatment. For several months, he was too ill to return to school, but in the spring of 1985 he began voicing his desire to return to his normal life by resuming classes at Western Middle School. When his mother met with school officials to talk about this possibility, she was met with resistance. Concerns about the health of other students, and that of Ryan himself, whose immune system had been ravaged by his illness, gave officials pause. In one of the earliest news articles about the issue, Western School Superintendent J.O. Smith asked:

You tell me. What would you do? . . . I don’t know. We’ve asked the State Board of Health. We’re expecting something from them. But nobody has anything to go by. Everybody wanted to know what they’re doing in other places. But we don’t have any precedent for this.

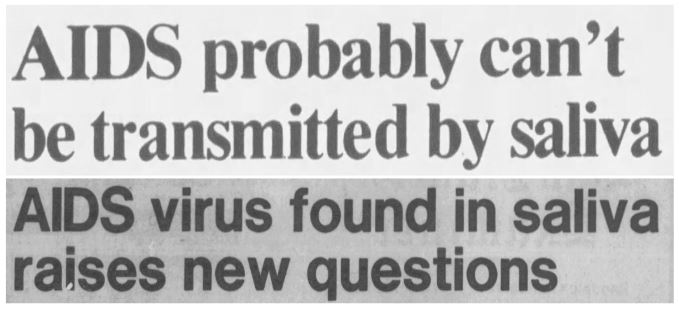

He was right. While a few schools had faced similar situations, the issues surrounding a child with AIDS attending school, namely, the risk this posed to other students, were far from settled. At this time, new and conflicting information came out at a dizzying pace. Most reports held that AIDS was not transmissible through casual contact, but others implied that you couldn’t rule out the possibility of it being passed through saliva, which would have made it a much bigger threat. With so much information—and misinformation—in the news cycle, the desire to hear from health authorities on the topic was understandable.

Three months later, the Board of Health released a document containing detailed guidelines for children with AIDS attending school:

AIDS/ARC children should be allowed to attend school as long as they behave acceptably . . . and have no uncoverable sores or skin eruptions. Routine and standard procedures should be used to clean up after a child has an accident or injury at school.

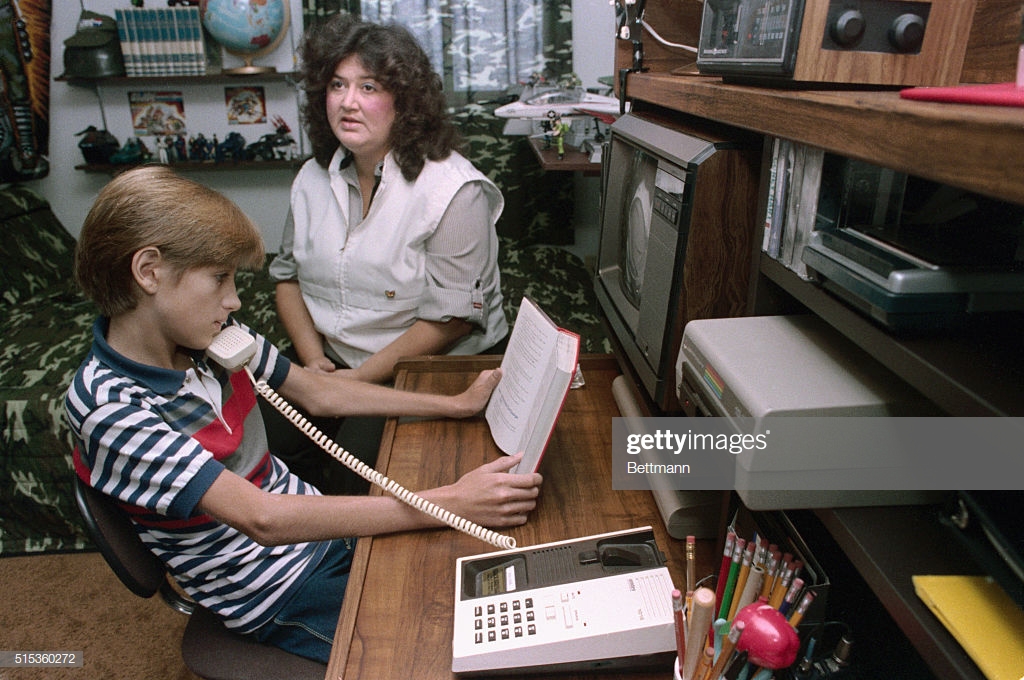

Despite this recommendation, Western School Corporation officials continued to deny Ryan admittance to class. Instead, they set up a remote learning system. From the confines of his bedroom, Ryan dialed in to his classes via telephone and listened to his teachers lecture. He missed out on visual aids, class participation, and sometimes the lectures themselves, as the line was often garbled or disconnected.

A November ruling, this time by the Department of Education, confirmed the Board of Health’s assertion that Ryan should be admitted to class:

The child is to be admitted to the regular classrooms of the school at such times as the child’s health allows in accordance with the Indiana State Board of Health guidelines.

Ryan returned to school for one day before the school filed an appeal and he was once again removed from class. A series of rulings, appeals, and other legal filings followed, ultimately ending when the Indiana Court of Appeals declined to hear further arguments and Ryan finally got what he and his family had fought so hard for—returning to classes for good. However, upon his August 25, 1986 return, Ryan faced intense discrimination from classmates and other community members. Addressing the Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic in 1988, Ryan recalled some of the more poignant moments from his time in Kokomo:

Some restaurants threw away my dishes, my school locker was vandalized inside and folders were marked ‘fag’ and other obscenities. I was labeled a troublemaker, my mom an unfit mother, and I was not welcome anywhere. People would get up and leave so they would not have to sit anywhere near me. Even at church, people would not shake my hand.

Because of these negative hometown experiences and his desire to evade oppressive media coverage, Ryan asked his mother if they could move out of Howard County. When the family decided to settle in Cicero, they couldn’t have known how drastically different their lives were about to become.

Tony Cook, who was the Hamilton Heights High School principal in the 1980s and is now a State Representative, heard through informal channels that Ryan’s family was moving into his school district in April 1987. The degree of media coverage surrounding Ryan’s battle to attend classes meant that Cook was well aware that his community’s reaction to the White family’s arrival would be heavily scrutinized. Thus, he set out on an AIDS educational crusade the likes of which had not been seen before.

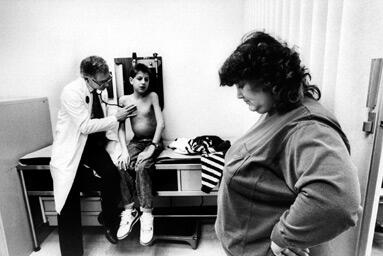

With the backing of his superintendent and school board, Cook quickly made the decision that not only would Ryan be admitted to the school, but there would be no restrictions placed on what Ryan was able to do in school (while in class in Western Middle School, he was not able to attend gym, used a separate restroom, and ate off of disposable trays with plastic utensils.) After gathering AIDS-related materials from the Indiana State Board of Health, the Center for Disease Control, major newspapers, and scientific journals, Tony Cook turned what was supposed to be his summer break into a months-long educational campaign.

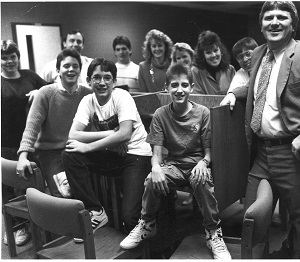

Throughout the coming months, Cook spoke about AIDS at Kiwanis groups, Rotary Clubs, churches, and to any group that asked. He sat in living rooms and at kitchen tables throughout the community, personally addressing the concerns of fellow citizens. The school developed a collection of AIDS education materials that could be checked out by students. Tony contacted members of the student government to ask them to act as student ambassadors, advocating on Ryan’s behalf with their fellow students and the media. The school staff went through additional training to prepare them for the possibility of a blood or other biohazard spill. By the time the school year came around, Cicero, Arcadia, and the surrounding area had some of the best informed populations when it came to AIDS.

The first few days of the 1987-1988 school year at Hamilton Heights High School were peppered with convocations in which Cook addressed each grade level to assuage any remaining concerns over sharing classrooms and hallways with Ryan. Students were encouraged to ask questions and support was provided for any feeling uncomfortable with the situation. Administration also offered to change class schedules to avoid conflict.

On Ryan’s first day of class, which was a week after school started, the campaign seemed to have been successful. As the press surrounded him on his way out, he smiled and said, “It went really great—really. Everybody was real nice and friendly.” Later, when speaking in front of the Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic, Ryan attributed his positive experiences at Hamilton Heights directly to the education campaign:

I am a normal, happy teenager again . . . I’m just one of the kids, and all because the students at Hamilton Heights High School listened to the facts, educated their parents and themselves, and believed in me . . . Hamilton Heights High School is proof that AIDS education in schools works.

When reflecting on the experience in a recent interview, Representative Cook spoke to the power of education to overcome even the most intense fear, “Yes, there were some folks that were uneasy and nervous, but we did see education overcome. And we saw a community that . . . trusted us.” One obstacle Ryan and the school faced was the sheer amount of publicity surrounding his move to Hamilton County. Hamilton Heights High School was an open campus–students traveled between three different buildings throughout the day–which would have made having members of the media on campus both distracting and potentially dangerous. But restricting access all together also wasn’t possible, as Ryan was a nationally-known figure by this time. The compromise was to have weekly press conferences during which Ryan, student ambassadors, and faculty could answer questions and update the press about the goings-on at the school, a practice that persisted throughout Ryan’s first full semester at Hamilton Heights.

After that first semester, the media began to lose interest in the story as it became more and more apparent that a mass walk-out or other dramatic event would not take place. The first time Tony Cook met Ryan, Cook asked why Ryan wanted so badly to attend school. During our interview with Representative Cook, he recalled that the fifteen-year-old Ryan, who by that time had been in the middle of a media storm for nearly two years, replied “’I just want to be a normal kid . . . I may die. So, for me, it’s important that I try to experience the high school experience as well as I can.” At Hamilton Heights High School, Ryan was able to do just that.

In the years following Ryan’s acceptance into Hamilton Heights High School, Ryan, Tony Cook, and others who had been involved in the educational program traveled around the country advocating for increased AIDS education. By August 1988, just one year after Ryan’s first day at Hamilton Heights, the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis began developing an exhibit centering on the issue:

While Ryan White zips around the country speaking out for AIDS education, the students of Hamilton Heights High School are telling children visiting The Children’s Museum in Indianapolis what it was like accepting Ryan into school . . . ‘I think everyone was uneasy at first,’ said one student on the videotape about Ryan’s coming to the school. ‘Education eased a lot of people’s minds,’ said another student.

Ryan White died on April 15, 1990 after being admitted to Riley Hospital for Children with a respiratory tract infection. In 2001, Ryan’s mother, Jeanne, donated the contents of his bedroom to the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, where it has been painstakingly recreated as part of the “Power of Children” exhibit. The museum also houses thousands of letters written to Ryan and his family throughout his illness. You can read the letters and even help transcribe them here.