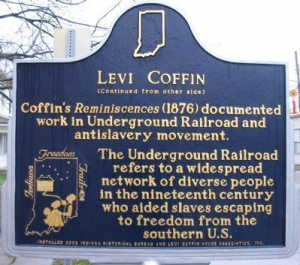

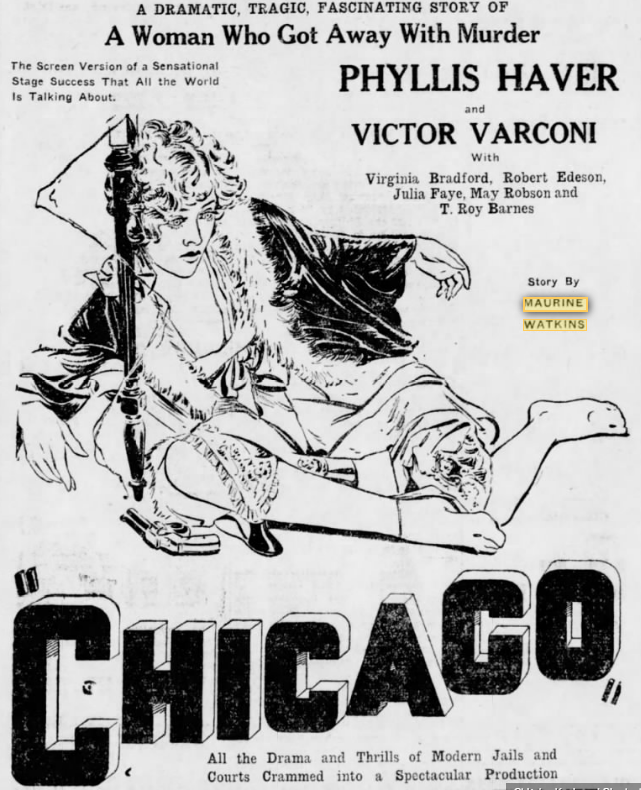

“Yes, it was me! I shot him and I’m damned glad I did! And I’d do it again-,” cried Roxie Hart, the achingly beautiful murderess conjured up by reporter-turned-playwright Maurine Dallas Watkins. Inspired by crimes she covered for the Chicago Tribune in the 1920s, Watkin’s 1926 play “Chicago” became an instant hit and has been continuously reinterpreted, from Bob Fosse’s 1970s production to the Oscar-winning 2002 Miramax film. The Crawfordsville, Indiana native’s take on women murderers, who employed charm and theatrics to convince sympathetic male jurors of their innocence, earned the praise of critics and theater-goers. The Los Angeles Times noted that year “critics claim that the play is without a counterpart in the history of the American stage.” In an era of instant, often fleeting social media-derived celebrity, Watkins’ fame-obsessed murderesses who kept the press enraptured seem more relevant than ever.

Born July 27, 1896 in Louisville, Kentucky, Watkins moved with her family to Indiana and attended Crawfordsville High School. According to a 1928 Indianapolis Star article, she started writing dramas from a young age. At 11-years-old, the Ladies’ Aid Society of the Crawfordsville Christian Church presented her “Hearts of Gold,” which generated $45. The St. Louis Star and Times described Watkins in 1928 as “simply dressed, with big, innocent-looking blue eyes and an exceedingly shy manner.”

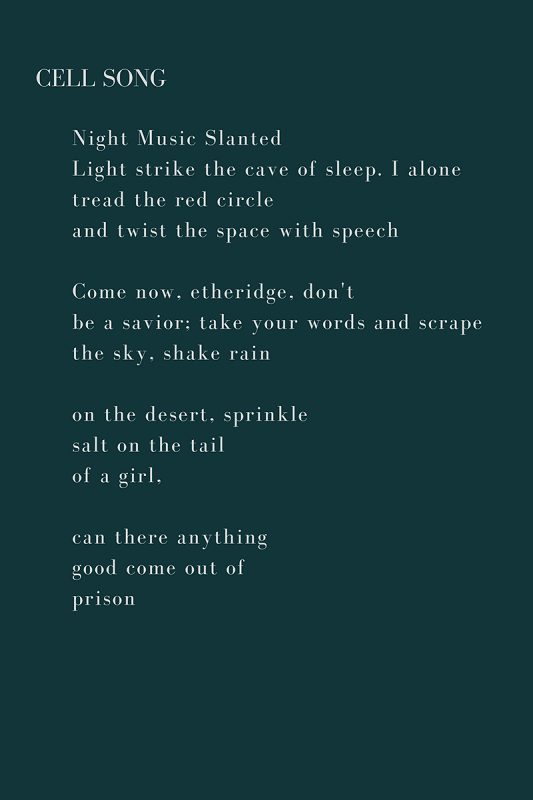

After studying at Butler University in Indianapolis and Hamilton College in Lexington, Kentucky, she sought experiences about which she could write and contacted the city editor of the Chicago Tribune. The newspaper, convinced by Watkin’s zeal, hired her to write about the city’s crimes from a “woman’s angle.” Her eight month stint as a “sob sister,” or women journalists who wrote about female criminals and were often sympathetic to their crimes (although not in Watkins’ case), inspired her to write “Chicago.” She described the piece as “‘a composite of many different happenings, while Roxy the heroine, was drawn from one of our leading ‘lady murderesses’-the loveliest thing in the world, who looked like a pre-Raphaelite angel, and who shot her lover because he was leaving her'” (Ind. Star).

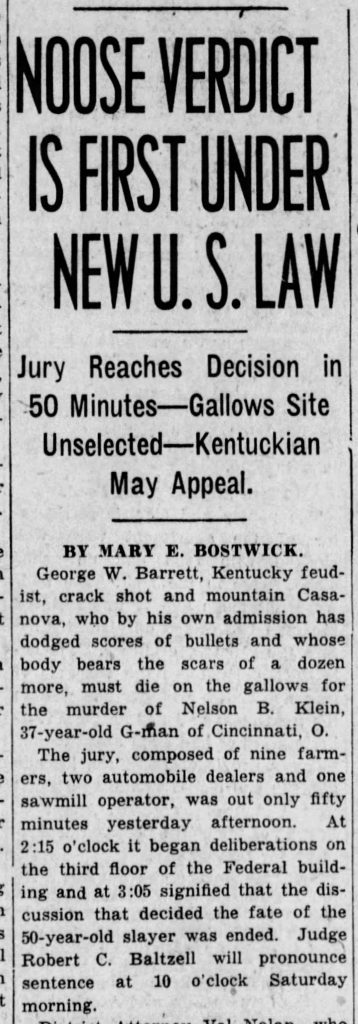

This murderess was one Mrs. Beulah Annan of Chicago, who confessed to killing her lover Harry Kalstedt. She was pronounced not guilty by a jury, swayed by her innocent persona and “man-taming eyes.” While Annan served as the inspiration for “Chicago,” the name of the play’s protagonist Roxie Hart was likely borrowed from a 1913 murder in Crawfordsville involving the lover of the deceased Walter Runyan. Like Annan, this lover was also praised for her captivating eyes and delicate features.

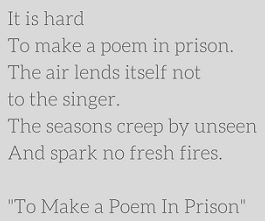

The St. Louis Star and Times noted that Watkins enjoyed this work for a period of time “because the psychological reactions interested her.” With literary inspiration in hand, she moved to New York and worked as a movie critic for the American Yearbook. She attended Professor George Pierce Baker’s playwriting class “47” at Yale University, drafting “A Brave Little Woman.” According to The Best Plays of 1926-27, upon completing the play Watkins, “being a thorough feminist,” approached play broker Laura Wilck, who “promptly bought it for herself and announced an intention of producing it. But before she got around to this the men interfered.” Well-known producer Sam Harris soon bought and changed the play’s name to “Chicago.” Best Plays attributed the piece’s success to Watkin’s “freshness of viewpoint,” “natural gift for writing,” and “interview with a lady murderess.” The Roaring Twenties provided the perfect canvas for Watkin’s literary skills and, as the Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News noted in 1927, “No period ever left itself wider open to lampooning than this in which the absurd antics of bootlegging, publicitizing, exploitation, crime and all the rest are commonplaces.”

The play achieved immediate stage success. According to a 1997 Chicago Tribune article, it ran for 172 Broadway performances. Its debut generated widespread anticipation and the Los Angeles Times reported in March 1927 that preparations were being made at the city’s Music Box Theater, “with stage and screen stars, literary prominents, civic officials and society leaders in attendance, the opening promises to develop into a social event.” The showing featured an undiscovered Clark Gable (who later married Hoosier actress Carole Lombard), portraying “Jake the reporter.”

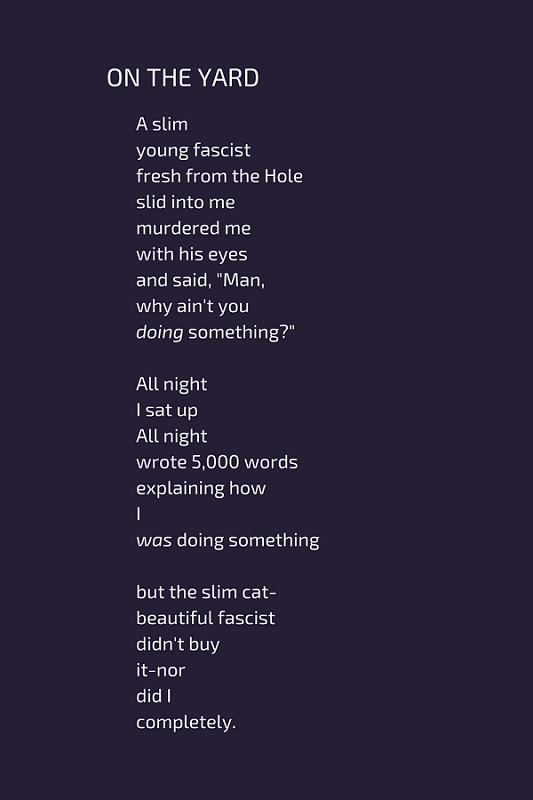

A review published by the Pittsburgh Daily Post noted that “Chicago’s” text was “so packed with knowledge and seasoned irony that any one could picture for himself the kind of toughened old buzzard of a sob-sister who would have knocked about enough to know how to write it.” The Arizona Republic published one of the more colorful and insightful reviews of the play’s impact on the public, noting that Watkins filled her “drama with comedy of terrific realty and, with never a word of preachment . . . and sends the audiences home converted to a skepticism that can hardly fail to have important results when enough people have seen the play.” As the scintillating third act concluded, the “audience staggers home, laughed out, yet somehow sadder and wiser, and realizing with tragic wonder that tomorrow the headlines will brazen forth some new female criminal.”

The Republic suggested that Watkin’s drama could change the public’s perception about these “pretty demons.” It added that her work was a “tremendous denunciation of the sacrilege by which the juryman, who should be the wisest and sanest of our guardians, is easily turned into a blithering come-on.” And, “best of all,” the satire was written by a woman “on the folly of men in their false homage to woman, their silly efforts to protect her while she dupes them.”

The Indianapolis Star reported that the reverend’s daughter still considered Indiana home, despite moving to New York following the success of her play. She recalled upon a return visit “‘I love it out in the country-life’s terribly complicated! You count the rings of the telephone to see if it is your number, and you have to go and meet the postman.'” The woman who wrote about a “flashy negligee of blue Georgette with imitation lace,” kept her hair “unbobbed” due to her father’s dislike of short hair.

Following the success of “Chicago,” Watkins continued to write, but never achieved the same level of literary acclaim. She was commissioned to dramatize Samuel Hopkins Adams’ novel Revelry, about the Harding administration’s Ohio Gang, for which she conducted research at the White House. In April 1927, the newspaper hired her to cover the trial of Ruth Snyder, who murdered her husband. The paper noted that Watkins, a sobless sister, would “deal with facts, without tears, in a notable author’s inimitable way, from her place at the trial table in Queens courtroom.” She reportedly moved to Hollywood, writing screenplays and articles for Cosmopolitan magazine. The author later settled in Florida, where she died of lung cancer in 1969. Watkin’s three act play cemented her legacy among the pantheon of accomplished Hoosier writers such as Pulitzer Prize-winner Booth Tarkington, I Love Lucy‘s Madelyn Pugh Davis, and Crawfordsville colleague Lew Wallace.