People from Florida are called Floridians. People from Maine are called Mainers. People from Washington are called Washingtonians. And people from Indiana are called…Hoosiers?

One of the most common questions we’re asked at the Indiana Historical Bureau is “What is a Hoosier,” and that’s often followed by “Where did that word come from?” As it turns out, people have been asking just that question for nearly two centuries.

Hoosier, now spelled ubiquitously “H-O-O-S-I-E-R,” as well as several other phonetical versions, can be traced back to the American South, where it was used as a derogatory term for uneducated, uncouth people. But just when the word began to be used specifically to refer to people from Indiana is hard to know.

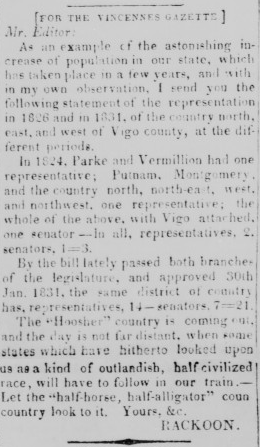

According to Indiana University Archives, the earliest known written use of the word can be found in a letter dated February 11, 1831. In the letter, written by G.L. Murdock to General John Tipton, Murdock replied to an advertisement and offered to deliver goods by steamboat to Logansport, Cass County. In closing, he mentioned, “Our boat will be named the Indiana Hoosier.” The earliest known printed instance of “Hoosier” can be found in a letter-to-the-editor of the Vincennes Gazette, just eight days after the Murdock letter was penned. In the letter, the author, who identified themselves as Rackoon, noted the increasing population of Indiana, saying,

According to Indiana University Archives, the earliest known written use of the word can be found in a letter dated February 11, 1831. In the letter, written by G.L. Murdock to General John Tipton, Murdock replied to an advertisement and offered to deliver goods by steamboat to Logansport, Cass County. In closing, he mentioned, “Our boat will be named the Indiana Hoosier.” The earliest known printed instance of “Hoosier” can be found in a letter-to-the-editor of the Vincennes Gazette, just eight days after the Murdock letter was penned. In the letter, the author, who identified themselves as Rackoon, noted the increasing population of Indiana, saying,

The ‘Hoosher’ country is coming out, and the day is not far distant, when some states which have hitherto looked upon us as a kind of outlandish, half-civilized race, will have to follow in our train. Let the ‘Half-horse, half-alligator’… country look to it.

It is pretty obvious by the lack of explanation that the authors of both of those passages expected that their readers would already be familiar with the word “Hoosier,” so it’s safe to assume that the word was in use, at least locally, before 1831. Throughout the early 1830s, usage increased significantly, but was still mostly found only in traveler’s accounts and local documents. That changed with the publishing of former state Representative John Finley’s poem “The Hoosher’s Nest” in 1833. The version of a Hoosier found in the following excerpt lacks the negative connotations associated with the original usage in the southern United States:

The emigrant is soon located-

In Hoosher life initiated:

Erects a cabin in the woods,

Wherein he stows his household goods.Erelong the cabin disappears,

A spacious mansion next he rears;

His fields seem widening by stealth,

An index of increasing wealth;

and when the hives of Hooshers swarm,

To each is given a noble farm.

Gone is the uneducated, uncouth backcountry man. He is replaced by an industrious farmer who is moving up in the world. It is likely that the moniker was first used as an insult towards people from Indiana, but they appropriated it and made it their own, much as colonial Americans had done with the term “Yankee” in the 1700s.

The publishing of “The Hoosher’s Nest” cemented the use of the word on a national scale, as it was picked up by other papers and published far and wide. It was not long before the first article to examine the origins of this most “singular” term appeared. Just ten months after “The Hooshers’ Nest” was published, the Cincinnati Republican ran a piece simply titled “Hooshier.”

The appellation of Hooshier has been used in many of the Western States, for several years, to designate, in a good natural way, an inhabitant of our sister state of Indiana. Ex- Governor Ray has lately started a newspaper in Indiana, which he names “The Hoshier” [sic]. Many of our ingenious native philologists have attempted, though very unsatisfactorily, to explain this somewhat singular term.

It goes on to list two unsatisfactory explanations of the etymology of the word before getting to the “real” root of the word.

The word Hooshier is indebted for its existence to that once numerous and unique, but now extinct class of mortals called the Ohio Boatmen. — In its original acceptation it was equivalent to “Ripstaver,” “Bulger,” “Ring-tailroarer,” and a hundred others, equally expressive, but which have never attained to such a respectable standing as itself. By some caprice which can never be explained, the appellation Hooshier became confined solely to such boatmen as had their homes upon the Indiana shore, and from them it was gradually applied to all the Indianians, who acknowledge it as good naturedly as the appellation of Yankee — Whatever may have been the original acceptation of Hooshier this we know, that the people to whom it is now applied are amongst the bravest, most intelligent, most enterprising, most magnanimous, and most democratic of the Great West, and should we ever feel disposed to quit the state in which we are now sojourning, our own noble Ohio, it will be to enroll ourselves as adopted citizens in the land of the “HOOSHIER.”

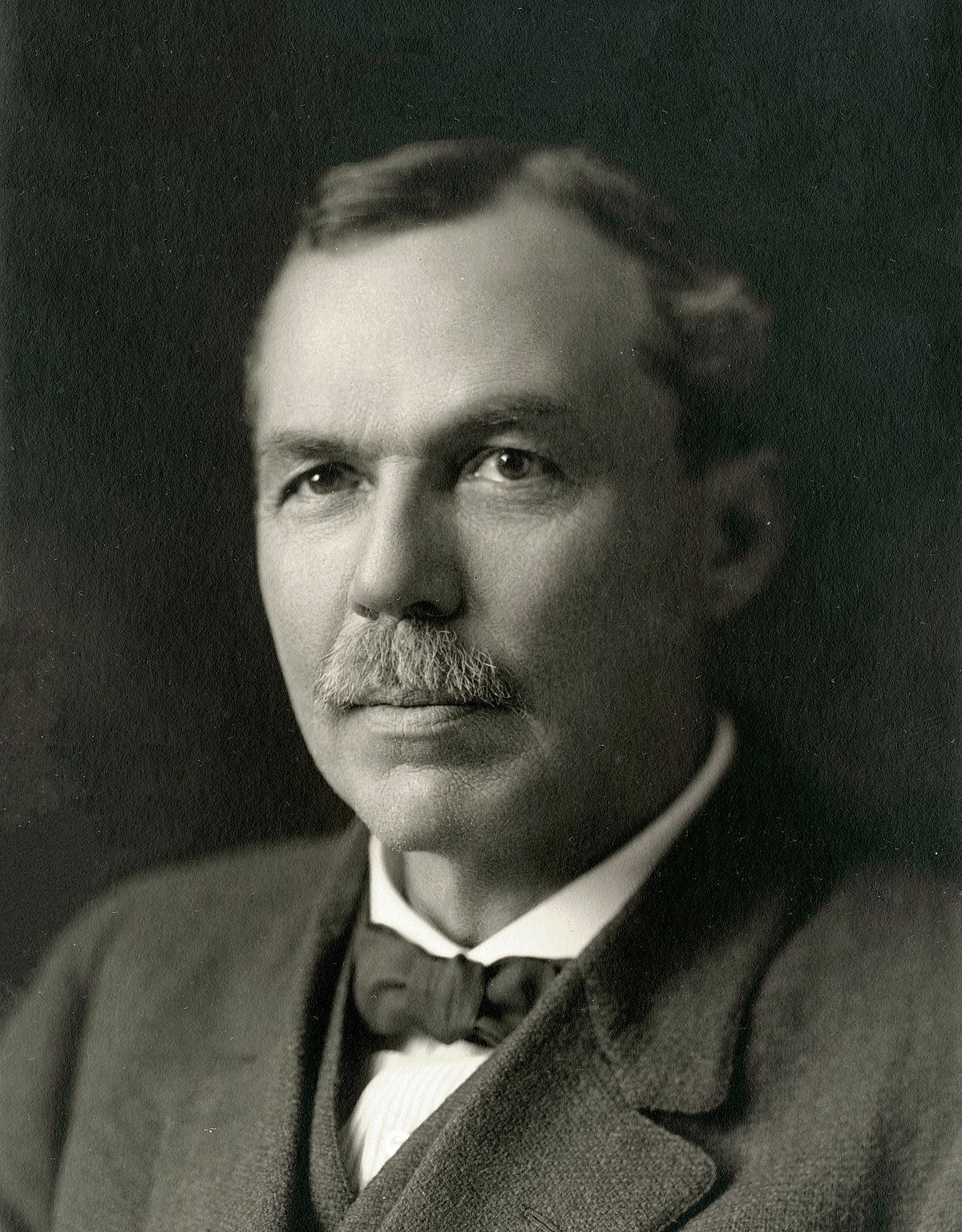

Again, this examination lacks any negative connotation with the word. Instead, it highlights the virtues of being a Hoosier. The next serious look into the word comes from historian Jacob Piatt Dunn, who wrote and rewrote his article entitled “The Word Hoosier” to near perfection – in fact, the eventual monograph that came from his articles, published in 1907, is still seen as one of the most thorough and accurate studies on the topic. It’s not often that such academic treatises stand the test of time.

Even after putting years of work into his article, Dunn concluded that we do not know exactly from where the word “Hoosier” derived, but dismissed many of the existing explanations as utterly ridiculous. He did, however, put forward three options regarding its origins.

First, he theorized that the word migrated up from the South as a slang term used for uncouth countrymen – this is the theory backed by the most evidence and seems to be the one Dunn favored, as he included a multitude of examples of this usage in the book. Second, he proposed an English root to the word. Similar terms can be found in early English dictionaries, such as “hoose,” “hoors,” and “hoozy,” that could conceivably have been corrupted into “Hoosier.” His third proposal sounds rather improbable on the surface. He conjectured that “Hoosier” came to America from India by way of England. According to Dunn, the Indian word “huzur” is “a respectful form of address to persons of rank or superiority.” He admitted that it seemed like quite a stretch but gave some examples of other words, such as “Khaki,” that made the same etomological journey.

But as soon as he finished reciting these possibilities he was quick to assure readers that he was not claiming these to be definitive answers, merely possibilities, saying, “It is not my purpose to urge that any one of these suggested possibilities of derivation is preferable to the other, or to assert that there may not be other and more rational ones.” The one thing he was sure about was that the word existed before it was used to describe a native Indianan.

Although many people have discussed, debated, and disputed the true origin of the word “Hoosier” in the years since Dunn’s 1907 essay, the only work to rival that of Dunn’s is Jeffrey Graf’s article “The Word ‘Hoosier,’” written for the Herman B Wells Library at Indiana University. He examines Dunn’s work, as well as that of other scholars who followed in Dunn’s footsteps. Graf’s 100+ page article is as thorough as it gets.

Not much has been added to the academic discourse in the last 100 years. It seems like most subsequent scholars begin with the goal of finishing the work Dunn started, covering the same ground he did, then throwing their hands in the air in frustration. One thing they have in common is a list of the various and sundry theories proposed throughout the years and we would be remiss not to cover at least a few of the more colorful origin stories to come about.

Theory 1

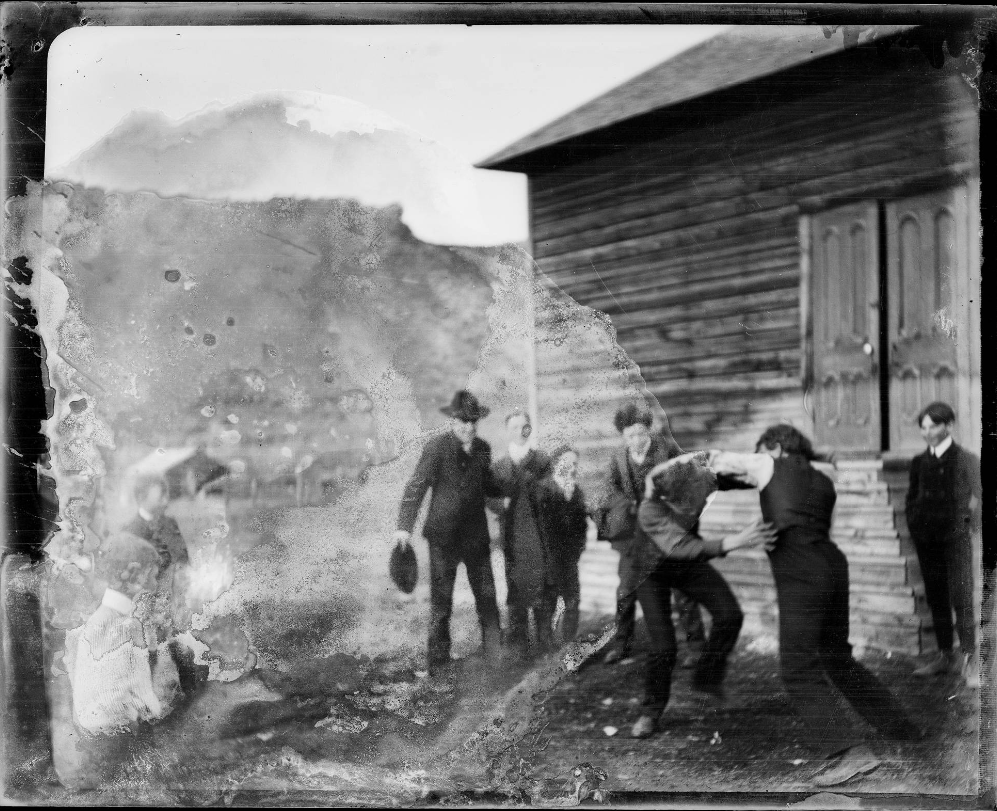

Frontier Indiana was a rough place that produced rough people. Rough but strong. Some of those rough, strong people found that the daily work of cutting down trees, farming, building houses with their hands, and chopping fire wood didn’t do quite enough to prove their strength to their fellow man. So they fought. They fought at house-raisings and log-rollings. They fought in the fields and in the woods. Those who were particularly adept at this so-called “wrastlin” were referred to as hushers, for they could quell their opponents into silence. One such husher found himself in New Orleans working as a boatmen when he felt the urge to demonstrate his rather remarkable strength. So, he fought not just one, but four men at once. And he bested them all. In his enthusiasm, he sprang up, shouting “I’m a Hussher!” But with his accent, it came out sounding more like “I’m a Hoosier!” The episode was picked up by some of the New Orleans newspapers and the “Hoosier” pronunciation came to refer to all boatmen from Indiana, and later all people from Indiana.

Theory 2

With just 65,000 people living in 23 million acres of Indiana, many people saw Indiana as a land of opportunity in the early years of the state. The opportunity to own land, to make a decent living, and to start over drew people to the state. Families made their way from all parts of the country to settle on the fertile soil of Indiana. And as they traveled the roughhewn roads, those families would sometimes come across a lone cabin in the wilderness. Weather they were looking for shelter, company, or both, often they would approach the cabin with a shout of “Who’s here?” to let the occupants know someone was coming. At this, the door would be opened and the guests welcomed. This scene played out again and again throughout the southern part of the state. Eventually, “Who’s here?” slowly morphed into “Whosere” and later to “Hoosier.” In the course of time, “Hoosier” came to describe all people from Indiana.

Theory 3

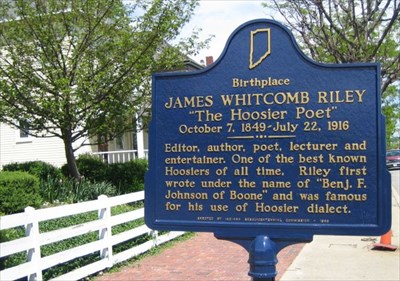

This theory comes to us from the Hoosier poet himself, James Whitcomb Riley. His version of the story includes the same stereotype of rough frontiersmen fond of fighting as did the “Hussher” theory. These settlers often congregated in taverns to share news and maybe a drink or two. When they got into their cups a bit, they always fell to fighting, often so violently that participants lost bits of their noses and ears. The morning after these ferocious rows, the barkeep would walk through the bar room and, seeing a stray ear on the floor, push it aside with his foot with a careless “Who’s ear?” This became so commonplace that it slowly morphed into “Whose year” and then to “Hoosier,” much like “Who’s here” supposedly did.

This theory comes to us from the Hoosier poet himself, James Whitcomb Riley. His version of the story includes the same stereotype of rough frontiersmen fond of fighting as did the “Hussher” theory. These settlers often congregated in taverns to share news and maybe a drink or two. When they got into their cups a bit, they always fell to fighting, often so violently that participants lost bits of their noses and ears. The morning after these ferocious rows, the barkeep would walk through the bar room and, seeing a stray ear on the floor, push it aside with his foot with a careless “Who’s ear?” This became so commonplace that it slowly morphed into “Whose year” and then to “Hoosier,” much like “Who’s here” supposedly did.

It seems like infinite theories exist, each more amusing than the last, all claiming to be the origin of the word Hoosier. All of them have one thing in common – they’re almost certainly apocryphal. It’s unlikely that we’ll ever know with any certainty exactly where the word “Hoosier” originated. However, from the 1986 film “Hoosiers,” to the Indiana University Hoosiers, to the 4,500 businesses with the word “Hoosier” in their names in the state, it is safe to say that there are no Indianans in Indiana–only Hoosiers.