See Part V to learn about the Cleveland Clique’s elusive grasp for control of the Bee Line Railroad.

In the four months since John Brough left the presidency of the Bee Line’s Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and Cleveland Railroad (IP&C) in February 1855, more than just its name had changed. The Hoosier Partisans’ move for autonomy would take concrete form as the Cleveland Clique tightened its grip on the Bee Line Railroad

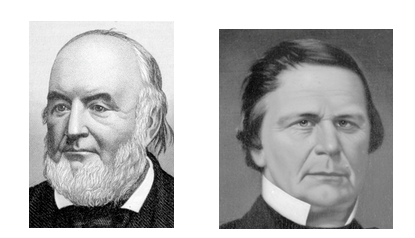

Calvin Fletcher, reluctantly elected president in John Brough’s stead, had met with a litany of key personnel and other midwestern railroad presidents to gain a broader perspective. He had also dealt with a variety of operational, cash flow and accounting issues left unaddressed by Brough.

As a result, by April the line’s Superintendent had resigned. At the same time, Fletcher engaged an individual to look into unaccounted for and delayed freight. He pushed for cost reductions at the engine shop at Union, and restructured the road’s finances. John Brough, reflecting on his own performance, acknowledged: “It appeared there were large discrepancies between the books of the Superintendent and those of the Secretary…As President I should have discovered these discrepancies and applied the remedy.”

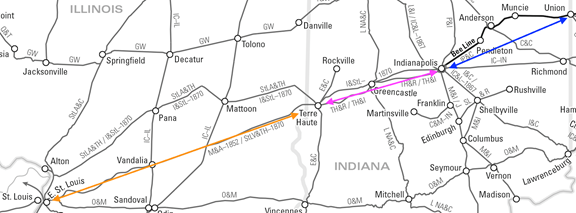

On top of Brough’s lapses while heading the IP&C, he had been removed as President of the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad (M&A) by late May 1855 in favor of Chauncey Rose – founder and former president of the Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad. The M&A, the Cleveland Clique’s bet to reach St. Louis, was in its death throes. It had taken a public relations beating at the hands of Illinois river town and Chicago politicians, who questioned the road’s legal legitimacy – and John Brough’s managerial track record. Investors abandoned the M&A, leaving Brough without portfolio.

Calvin Fletcher, frustrated by what he discovered as president of the IP&C, informed the Hoosier Partisans: “I feel that my official duties in the RR are oppressive & that I must leave them…There is a degree of corruption in relation to it that I cannot arrest—or rather the effects of which already passed that I cannot overcome.”

As the July 1855 annual meeting approached, the Partisans pushed Fletcher to continue on as president. They soon faced reality: he would not remain. As late as the day before the meeting Fletcher could not figure who would become his successor. It soon became clear, however, the Cleveland Clique had been making plans as well. Incredibly, John Brough would be resurrected not only to retake his prior role at the IP&C, but also be anointed as president of the Bee Line’s Bellefontaine and Indiana Railroad (B&I) at the same time!

Brough’s operational and financial shortcomings would have been obvious to the Cleveland Clique by then. On the other hand he was loyal, politically savvy, and possessed an Ohio pedigree. Given the newly redefined and more limited scope of the president’s role, and with strong Clique operational and financial expertise now present on both boards, Brough was serviceable.

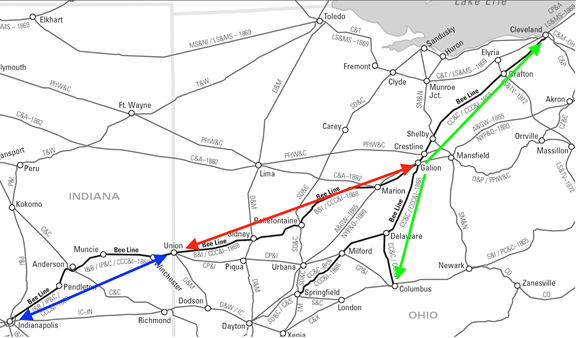

Effectively, the Cleveland Clique would now control both the B&I and IP&C. While not yet legally consolidated, the two roads would be run as one while John Brough and the Clique considered the calculus to officially bind them together.

Sparked by Brough’s Clique-masterminded elevation to the dual Bee Line presidential roles, the IP&C’s Hoosier Partisans squirmed under the terms of the joint operating agreement foist upon them by the Cleveland Clique the year before. Both the perpetual nature of the contract and mandate to consolidate with the B&I “at the earliest possible moment” were not sitting well. Discovering the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CC&C) had never technically executed the contract, the Hoosier Partisans made a move to modify its language.

By the IP&C’s March 1856 annual meeting, revised terms of the joint operating agreement had been hammered out. A newly reconstituted and more representative overall executive/finance committee was arranged. At the same time, the contract term was reset to five years, instead of being perpetual. Any party to the contract could now terminate it with three months’ notice. However, this clause could only be exercised after the agreement had been in place for three years.

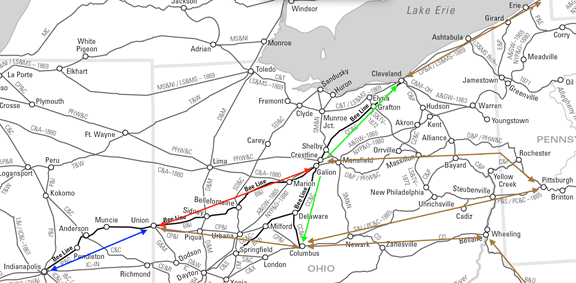

Fortunately for the Hoosier Partisans, the IP&C’s three-year joint operating obligation ended as the Columbus, Piqua and Indiana Railroad (CP&I) finally reached Union in the spring of 1859. Now the IP&C could anticipate a substantial revenue boost as freight and passengers traveled to/from Columbus across CP&I track to Union. From Columbus, Pittsburgh could now be reached – and the Pennsylvania Railroad headed to Philadelphia – via affiliated lines.

Union and the IP&C were proving to be a pivotal funnel for other traffic as well. Freight and passengers headed to/from New York across the CC&C and aligned roads to the fledgling New York Central Railroad at Buffalo would find their way to Union. Similarly, via the CP&I link between Union and Columbus OH, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) could now be accessed at Wheeling WV. And, courtesy of a new through-line arrangement connecting the B&O’s eastern terminus at Baltimore with New York City, a second alternative for reaching this center of commerce from Union became a reality.

The IP&C would be the clear beneficiary of these new connections to the east – if only it could effect a separation, if not a divorce, from the B&I as well as the CC&C. Then, standing individually, the IP&C could strike lucrative through-line agreements with each of the eastern trunk lines and their local affiliates. By way of these arrangements, the Hoosier Partisans could once again regain control over their own destiny.

At the March 1859 IP&C board meeting, Partisan David Kilgore proposed a three-person board committee be appointed to “pursue a line of fair and impartial conduct between our two connections at Union.” The concept was for the IP&C to direct traffic under its control and destined for New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore to these connecting roads “in proportion to the trade and travel received from the several points named above.”

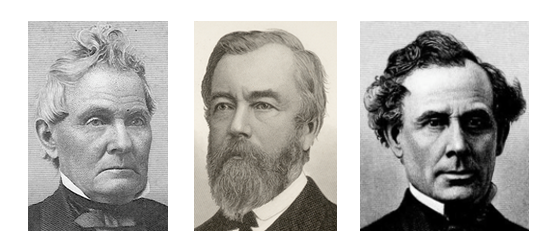

In addition to David Kilgore, ubiquitous Indiana railroad construction engineer, recent president of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad and IP&C board/executive committee member Thomas A. Morris, and Cleveland Clique and CC&C strongman Stillman Witt were appointed to the committee.

The stars were aligning from an operational standpoint as well; a March 28 letter from the receiver of the CP&I announced they “will be prepared in a very few days to transport passengers and freight” between Union and Columbus OH.

A crucial series of IP&C-arranged meetings with presidents and general managers of several of the eastern trunk lines and their Ohio-affiliated roads took place in Columbus, Ohio that May. The importance of Union and the IP&C’s Indianapolis connection west toward St. Louis were obviously not lost on the roster of kingpins who decided to attend the Columbus confab.

As might be expected, there were two distinct perspectives on the IP&C’s postulated autonomy. Those regional lines aligned with the Pennsylvania Railroad or B&O via CP&I connections at Columbus OH endorsed the IP&C’s move toward independence. Not surprisingly, those roads associated with the New York Central via Bee Line alignments at Cleveland, or with the Pennsylvania Railroad via the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad [O&P] (passing near the B&I’s eastern terminus at Galion OH) took the opposite position. Among this group was the CC&C’s then president, Leander M. Hubby.

Shortly after the meeting, as Hubby contemplated the implications of the IP&C’s stratagem – with its alternative access to New York City via the B&O – he balked. “This company would not quietly submit to receiving a divided business from the IP&C.” Hubby went on, and to the heart of the matter, “this company contributed largely in money and credit to the completion and opening of the Bellefontaine Line…I think it my duty to say…this Company…will at once form other connections which are being offered them.”

Bee Line financier Richard H. Winslow of Winslow, Lanier & Co. tag-teamed with Hubby, mounting an attack on the IP&C’s soft financial underbelly. “In view of your embarrassments growing out of the large debt falling due the 1st of January next, we should think it a hazardous experiment and one that may lead to very bad consequences.”

In many respects the Hoosier Partisans’ dream of an independent IP&C had been dashed years before when it accepted the financial help of “foreign” interests—be they in New York, Cleveland, or Europe.

Hollow recognition was paid to the Partisans in the wake of the Union episode. At the annual IP&C board elections in July 1859, Thomas A. Morris was elected president. In turn, John Brough stepped down from the IP&C presidency but continued to hold dual roles as president of the B&I and chairman of the overall Bellefontaine Line executive committee. The title of general superintendent was also added to his dossier. Brough and the Cleveland Clique would control eight seats on the IP&C board to the Hoosier Partisans’ seven.

At the May 1860 board meeting, extension of the revised Bee Line joint operating contract was considered. Swallowing its pride and with a financial gun to its head, the IP&C board reluctantly moved to accept it. If anything, the Union episode crystallized the Cleveland Clique’s determination to drive the B&I and IP&C to a formal and final consolidation under their direct control.

And while the IP&C’s contract extension with the B&I had taken more than a year to be resolved, the Union episode hastened the day when the IP&C would no longer exist as a separate entity. And with it, the Hoosier Partisans’ dream of maintaining control of their own destiny faded to a smoldering ember.

Check back for Part VII to learn more about the push and pull of the Hoosier Partisans and Cleveland Clique, leading to the legal consolidation of the Bee Line component railroads.

Interested in the Bee Line Railroad?