There are a lot of theories about the origin of the word “Hoosier.” And while we’ll probably never find one definitive source for this nickname for people from the State of Indiana, we sure don’t get tired of trying! IHB alone has a webpage, blog post, and podcast episode dedicated to this very question. The Indiana Magazine of History dedicated an entire issue to the various theories and the IUPUI Center for Digital Scholarship’s Chronicling Hoosier project maintains a database of the various theories and related documentation. In recent years, the Harry Hoosier theory has gained some traction, so let’s take a look at how it stacks up to the other “Hoosier” origin stories.

Early Uses of Hoosier

According to Indiana University, the earliest known written use of the word “Hoosier” comes from an 1831 letter written by G. L. Murdock to John Tipton stating that his steamboat would take the name “the Indiana Hoosier.” The earliest printed use appeared in the Vincennes Gazette just days later, commenting on the increasing population of “the ‘Hoosher’ country,” aka Indiana. Both writers used the term in a manner that shows they expected the reader already knew the word and its meaning, so it must have been in use for some time. In 1833, Representative John Finley published his poem “The Hoosher’s Nest,” which characterizes people from Indiana as upwardly mobile farmers. According to an IHB blog post: “It is likely that the moniker was first used as an insult towards people from Indiana, but they appropriated it and made it their own, much as colonial Americans had done with the term ‘Yankee’ in the 1700s.” From this early usage in the 1830s, the term appeared more regularly and almost immediately people began to speculate on its origin . . . something that continues to this day. And lately, the quest to find one neat answer has turned to the theory surrounding Harry Hoosier for a potential resolution.

Who was Harry Hoosier?

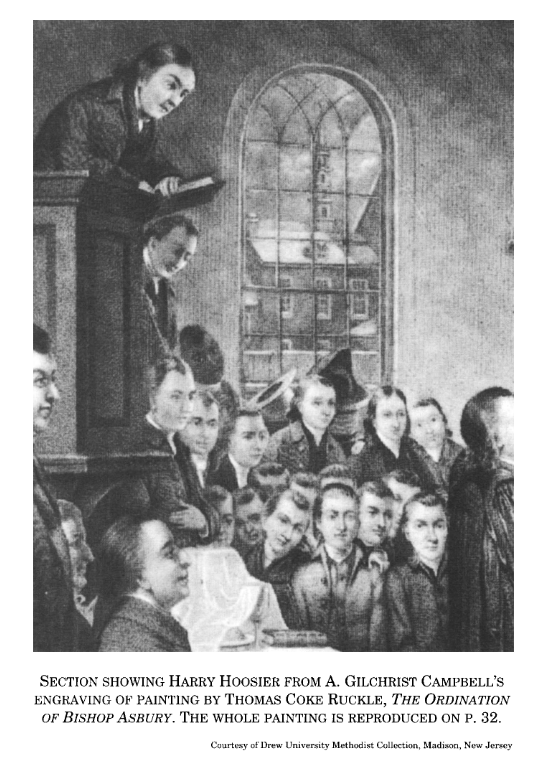

Harry Hoosier (circa 1750-1806) was a Black Methodist lay preacher whose elegant speeches made a lasting impression on listeners. Enlightenment thinker Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, is reported to have said “making allowances for his illiteracy [Hoosier] was the greatest orator in America.” By 1780, Hoosier was travelling with Methodist Episcopal Bishop Francis Asbury, sometimes speaking after Asbury and soon drawing large crowds of both Black and white listeners. Over the following decade, Hoosier spoke in Eastern and Southern states but never in Indiana. If you’d like to know more about Harry Hoosier’s life and career, access the two scholarly articles freely accessible via the Indiana Magazine of History (IMH) in their 2016 “What Is A Hoosier?” bicentennial issue. Harry Hoosier was undoubtedly a significant figure in American history, but what about to Indiana history specifically? If he didn’t come to Indiana, how could Hoosiers, meaning people from Indiana, be named for him?

Argument for Harry Hoosier as the Origin of the Term “Hoosier”

This is the question scholars and amateur historians have been recently tackling. The most extensive, and oft-cited study of the Harry Hoosier theory comes from William D. Pierson, professor of history at Fisk University. You can read his IMH article, “The Origin of the Word ‘Hoosier:’ A New Interpretation” here. Pierson builds on early theories explored most notably by Jacob Piatt Dunn at the start of the twentieth century that assume both a southern origin and a derogatory original meaning for the word “Hoosier.” You can read more about Dunn’s explorations of the origins of the word “Hoosier” through IHB’s Indiana History Blog blog or read Dunn’s 1905 IMH article. In short, Pierson agrees with Dunn on two points: 1. The word “Hoosier” was originally intended to be derogatory and 2. The term originated in the South. It should be noted that these assertions are still theoretical and many early sources do not actually paint Hoosiers in negative light. (Learn more).

In order to argue that the term “Hoosier,” as used in a derogatory fashion, could stem from Harry Hoosier’s career, Pierson makes his own leap of faith. Pierson posits that perhaps southern Baptists would have seen the southern Methodist supporters of Harry Hoosier’s message as “unsophisticated and unlettered.” Pierson then concludes that “it does not seem at all unlikely that Methodists and then other rustics of the backcountry could have been called ‘Hoosiers’ – disciples of the illiterate Black exhorter Harry Hoosier – as a term of opprobrium and derision.” This is an interesting theory, but there are no primary sources to support it. Pierson himself asserts that his theory “is admittedly as circumstantial as all the other hypotheses.”

The Unravelling Harry Hoosier Theory

Harry Hoosier did not preach in or near Indiana. Pierson argues that the term originated in the South and moved with settlers as they came to Indiana. But many pioneers from Virginia and the Carolinas, where Harry Hoosier did preach, also settled in Tennessee and Kentucky. So, how did the term end up applying to people only from Indiana? Pierson posits that “an original antislavery and African American reference in the term would explain why ‘hoosier’ . . . settled on the inhabitants of the free and more Methodist territory of Indiana after passing lightly over similarly uncouth frontiersmen in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky who were also often called ‘hoosiers.’” Here Pierson misunderstands the slavery views of both the Methodist Church and the majority of early settlers of Indiana.

While Harry Hoosier himself spoke against slavery, the Methodist church in the U.S. was split on the issue. Among believers, views ranged from vigorous support for slavery to abolition. Some southern Methodists, including church leaders, were also slaveholders. It is also important to remember the devastating impact of early Indiana practices and policies toward Black Hoosiers. Many early Hoosiers worked to prevent free Black settlers from entering the state, allowed enslavers to retain their enslaved or indentured workers for generations, and actively participated in the return of escaping self-emancipated people to their enslavers. While free Blacks and anti-slavery Quakers also shaped the state, the majority of early Hoosiers were not necessarily anti-slavery, and they definitively opposed Black settlement. Furthermore, when Indiana created its 1851 constitution, Hoosiers voted overwhelmingly for a provision prohibiting African American settlers from entering the state.

Pierson concludes that the Harry Hoosier etymology “would be the simplest derivation of the word and, on simplicity alone . . . is worth serious consideration.” However, most historians wouldn’t consider “simplicity” to be a sound historical argument. In his 2018 paper for Indiana University’s Herman B Wells Library, scholar Jeffery Graf critiques Pierson’s argument: “Readers may sense that the article has a certain wouldn’t-it-be-great-if quality, as though the author perhaps never entirely believed in his own argument, or feared no one else would.” It should also be noted that the IMH published Pierson’s article simply as one of several theories. And that probably summarizes the Harry Hoosier theory best. It’s interesting to muse about, certainly, but there are no primary sources to give it more weight than any other theory.

Back to the Sources

Primary sources, including newspaper articles from the period, show “Hoosier” being applied as a moniker for people from Indiana in a neutral or positive manner as early as the 1830s. In an age of slower communication and travel, it is unlikely that in the approximate decade between Harry Hoosier’s death and the change in the usage of “Hoosier” that the term rocketed from Virginia and North Carolina through Tennessee and Kentucky to end up in Indiana. Meanwhile, on this rapid journey, Pierson asks us to believe it also shed its connection to Harry Hoosier, took on a derogatory meaning for Methodists, lost its derogatory meaning for Methodists, and arrived in Indiana, and was adopted there by all of the people in the state. Again, interesting, but there just isn’t any hard evidence. Stephen H. Webb, late associate professor of religion and philosophy at Wabash College, who wanted to support Pierson’s theory because it “makes a better story” than other theories, conceded that “the evidence for the connection between his name and Indiana’s nickname is circumstantial, which leaves room for skepticism.”

“An Argument without End”

As the historian Pieter Geyl famously stated, “History is indeed an argument without end.” So, we encourage you to make up your own mind about the origin of the word “Hoosier.” IUPUI’s Chronicling Hoosier project presents all of the sources and data that they collected on the early uses of the term on their free and searchable website. But in all reality, we probably won’t ever know definitively or be able to neatly wrap up the argument. Like a lot of slang terms, people were using “Hoosier” in different ways. Chronicling Hoosier reports:

Instead of a tidy trajectory from one meaning to another, this newspaper analysis suggests hoosier has always had a variety of meanings and connotations. It was used to refer to individuals from “the West,” which in early 19th century included Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and parts of Michigan, Wisconsin, and sometimes Kentucky. However, there is also clear and consistent evidence that during the same time period it was just as often a term for referring exclusively to Indianans.

The project concludes: “We suggest that the term’s definition, like all language, was and remains in flux.” This answer isn’t as satisfying as attributing the origin of the term to one great man. But sometimes history is a bit messy. As Hoosiers, known for our “Hoosier hospitality” after all, it seems perfectly Hoosier-y to welcome all the theories, from Riley’s “whose ear” joke to etymological arguments from scholars. And as more and more sources are digitized each year, it’s likely we’ll find even earlier references than we currently have. Now whether these sources will add clarity or more confusion . . . we’ll have to stay tuned, Hoosiers!

Sources and Further Reading

IUPUI Center for Digital Scholarship, Chronicling Hoosier, http://centerfordigschol.github.io/chroniclinghoosier/index.html.

Indiana Historical Bureau, “The Word ‘Hoosier:’ An Origin Story,” Indiana History Blog, June 12, 2018, https://blog.history.in.gov/the-word-hoosier-an-origin-story/.

Jeffrey Graf, The Word “Hoosier,” Scholars’ Commons, Herman B Wells Library, Indiana University Libraries, Bloomington, https://libraries.indiana.edu/sites/default/files/The%20Word%20Hoosier-Revised-and-Expanded-2018.pdf.

“What Is A Hoosier?: A Bicentennial Issue,” Indiana Magazine of History 112: 3 (September 2016): 149-252, https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/issue/view/1656.

William D. Piersen, “The Origin of the Word ‘Hoosier’: A New Interpretation,” Indiana Magazine of History 112:3 (September 2016): 218–225, https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/25482/31292.

Stephen H. Webb, “Introducing Black Harry Hoosier: The History Behind Indiana’s Namesake,” Indiana Magazine of History (September 2016): 112, Issue 3, 226–237, https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/25483/31293.

Brian D. Lawrence, “The Relationship between the Methodist Church, Slavery and Politics, 1784-1844,” Master of Arts in History Thesis, Department of History, Rowan University (May 4, 2018), https://rdw.rowan.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3573&context=etd.

Sources on treatment of African Americans in early Indiana:

Article 13, Indiana Constitution of 1851, Constitution Making in Indiana, edited by Charles Kettleborough (Indiana Historical Bureau, 1916, reprint 1971), accessed Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/about-indiana-history-and-trivia/explore-indiana-history-by-topic/indiana-documents-leading-to-statehood/.

Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana Before 1900 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1985, reprinted Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993), 68-69; Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana: A Study of a Minority (Indianapolis, 1957), 23-30.

“Indiana and Fugitive Slave Laws,” Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/for-educators/all-resources-for-educators/resources/underground-railroad/gwen-crenshaw/indiana-and-fugitive-slave-laws/.

Donnell v. State 1852, State Historical Marker 16.2007.1, Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/donnell-v-state-1852/.

John Freeman, State Historical Marker 49.2006.2, Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/john-freeman/.

Mary Clark, State Historical Marker 42.2009.1, Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/find-historical-markers-by-county/indiana-historical-markers-by-county/mary-clark/;

Polly Strong Slavery Case, State Historical Marker 31.2016.1, Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/find-historical-markers-by-county/indiana-historical-markers-by-county/polly-strong-slavery-case/