Along with many of her fellow 19th-Century sisters of the pen, Susan Elston Wallace and her work are little known to us today. These female authors practiced their craft seriously and sold well, yet were never regarded as important as male writers whose subjects were presumed to be nobler, of higher value. When fine work by women disappeared and men’s work became classics, an unknown cost fell upon our culture and our vision of ourselves as a nation.

As a writer, Susan Wallace (1830-1907) possessed certain attributes that partially set her apart her from the “female writer” stereotype. Initially, as a young woman she had more or less lived the stereotype by publishing poetry on domestic subjects. One of those poems was anthologized and widely circulated in a children’s textbook.

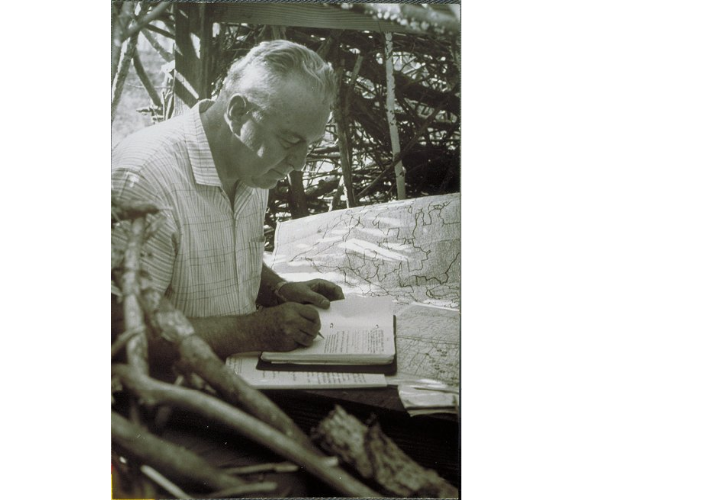

Later in life, she was exempted from ordinary critique as a “female writer” because she was the wife of General Lew Wallace, author of Ben-Hur, the best-selling book of the 19th century. (Only the Bible sold more copies). Lew was a prolific writer and a man of great personal accomplishment, who, among other distinctions, was a Civil War general, Governor of New Mexico Territory (1878-1881), and an ambassador to Turkey. Susan, without a doubt, was Lew’s collaborator and co-researcher. She was fully recognized by him as an intellectual and literary equal. Given this unusual and little-known partnership, it is no wonder that deep knowledge of the world and of its peoples mark both of their works. Surely both partners strongly influenced the other’s work. Whether they were living in Crawfordsville, Indiana, or in the New Mexico Territory, or in the Ottoman Empire, both husband and wife engaged in writing projects.

It is the New Mexico piece of Susan’s writing career that I will use to demonstrate Elston Wallace’s talent as a non-fiction writer, whose insights track a line of prescient environmental thinking. Her writing style is not only alive with ideas, it exhibits a freshness and wit that makes it inviting to contemporary readers.

Elston Wallace’s book about her New Mexico sojourn is called The Land of the Pueblos. It is comprised of twenty-seven essays, first published as “travel pieces” in prestigious national magazines and newspapers like the Atlantic Monthly, the Independent, and the New York Tribune. Being published in such influential East Coast periodicals speaks of the high regard in which her writing was held at the time. In these essays, Susan did not write a word about the many social duties—the teas, the formal receptions, entertaining visiting dignitaries—she would have performed as the wife of the Governor of New Mexico Territory. Nor does she write about her husband in his official capacity. Rather, she applied her excellent educational background and her intellectual curiosity to learning and writing about New Mexican natural history and human history.

Elston Wallace also holds the rare honor of having saved much of New Mexico’s written colonial history, which had been forgotten in an outbuilding adjacent to the Governor’s Palace in Santa Fe. There, Elston Wallace came upon and then personally helped salvage much of the Territory’s surviving early recorded history, a topic about which she wrote vividly. These documents tutored her. They spurred her curiosity and inspired many of her essays.

***

It was New Mexico, though, that made Elston Wallace aware of environmental issues. She was an astute observer of the natural world, learning names and habits of the plants and animals; she studied landforms and how rivers ran. Her ability to write about these things gives her work its most notable signature. Increasingly more knowledgeable about her surroundings and thereby more fully conscious of how human life in New Mexico had been shaped, Elston Wallace soon apprehended how the Spaniards, in particular, had affected the land and its original inhabitants. In her first essay, Elston Wallace makes clear that the “greed of gold and conquest” had despoiled New Mexico.

She also proves herself as an able thinker regarding how land and people’s fates are intertwined, such as this example:

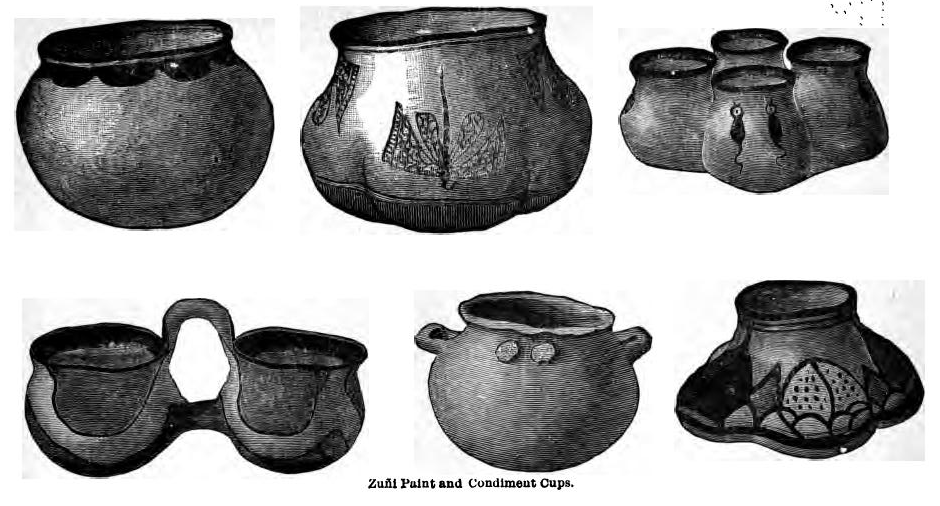

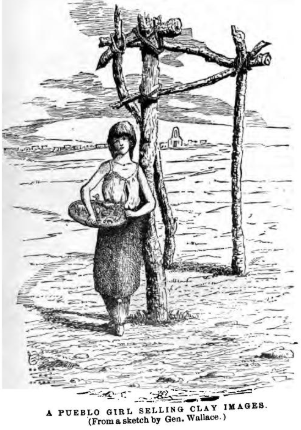

Four hundred years ago the Pueblo Indians were freeholders of the vast unmapped domain lying between the Rio Pecos and the Gila, and their separate communities, dense and self-supporting, were dotted over the fertile valleys of Utah and Colorado, and stretch as far south as Chihuahua, Mexico. Bounded by rigid conservatism as a wall, in all these ages they have undergone slight change by contact with the white race and are yet a peculiar people, distinct from the other aboriginal tribes of this continent as the Jew are from the other races in Christendom. The story of these least known citizens of the United States takes us back to the days of . . . the . . . great Elizabeth.

Note how in this passage Elston Wallace identifies the “vast unmapped domain” of the Pueblos and identifies their communities as “separate,” “dense,” and “self-supporting.” She identifies the land as fertile and the Pueblos as having a distinct culture, comparing them favorably to Jews among Christians. She calls the Pueblos “citizens.”

Elston Wallace’s use of the term “conservative” in this passage may be accurately rendered as “stable.” So, the nature of the Pueblo peoples, she says, have “undergone [only] slight change by contact with the white race.” By using this terminology, she points toward stabilizing forces that were afoot in 19th-Century America, when colonies promoting shared, stable agrarian living were being intentionally created. The Shakers, New Harmony, and the Amanas were and are communities so notable that their names and accomplishments come down to us today. In the previous passage, Elston Wallace describes the Pueblo communities, their governance, and their farming practices with phrases admired by her own culture and era. New Mexico’s native peoples were freeholders; they were self-supporting; they formed communities; they were citizens. Few other historians of the period write about the Pueblos at all, let alone view them as central to the history of the land they inhabit, and as admirable people.

It can be argued, of course, that Elston Wallace’s progressive fellow citizens of the period had a habit of idealizing Native Peoples and had a strong aversion (call it prejudice) against Catholic Spain. That being said, Elston Wallace’s analysis and her rich empathy supported by historical knowledge and argumentation make her work stand apart. Her brave voice stands in strong contrast to typical histories of her day and those written through the middle of the 20th century. A pertinent example is Paul Horgan’s The Centuries of Santa Fe (1956), which presents the conquest version of New Mexico’s history as thoroughly Eurocentric. In this version, the Mexicans succeeded the Spanish and the Americans succeeded the Mexicans until the New Mexican piece of America’s Manifest Destiny fell into place in 1846.

Given this widely accepted version of conquest history that Horgan and other historians espouse, it is no wonder that he not only displaces the Pueblos, he displaces Elston Wallace as a New Mexican historian who understands and chronicles their worth and richness. Ironically, Horgan credits Governor Lew Wallace, not his wife, as saving “what he could of the collection of [New Mexican historical] documents already scattered, lost, or sold.”

Horgan’s “authoritative” reporting, so common among mainline historians of the 20th century, renders the Pueblo peoples, their land, and the intelligent woman who told their stories in the l880s invisible. No matter how accurate and astute Elston Wallace’s argument was, it had no efficacy since it was not “remembered” in mainstream histories of New Mexico and the West. Such an argument, had it been heard and then acted upon, might have reshaped our history.

In an era of unstoppable exploration and exploitation of the West and its mineral resources, Susan Elston Wallace saw, understood, and wrote about a broader, deeper story, one which speaks of how we as people can best live on the land. She vividly chronicles what happens when natural patterns are disrupted. In our century, we would regard Elston Wallace’s vision as a strongly environmental one, central to our 21st-Century understanding of essential sustainability.

So, while Elston Wallace certainly did entertain the intellectual readers of the East Coast and Midwest with tales of Montezuma and adventures of travel in the Wild West, in The Land of The Pueblos, she also boldly introduced her readers to what happens when “a native self-sustaining people, independent of the Government, the only aborigines among us not a curse to the soil” are abused along with their land through the claims of colonialism.

During the late 19th century, it was widely assumed that men make history. Elston Wallace challenges that point of view and deserves a place in our history as an excellent non-fiction essayist. She also deserves a place as a dissenter to colonial history’s single, obliterating story of man as controller of nature. Susan Wallace was an early environmentalist: she gave voice to New Mexico’s landscape and to its original peoples. Researchers have exciting work to undertake in the Susan Elston Wallace archives.