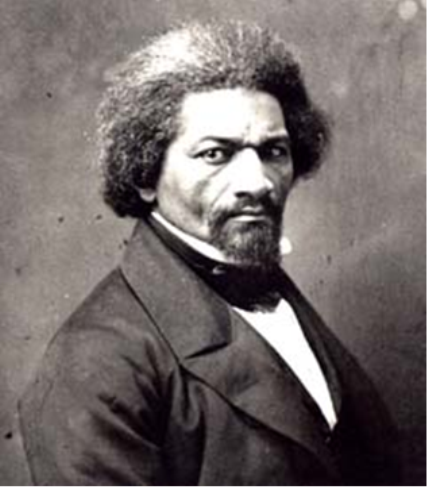

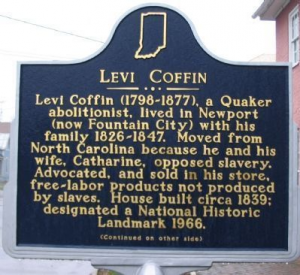

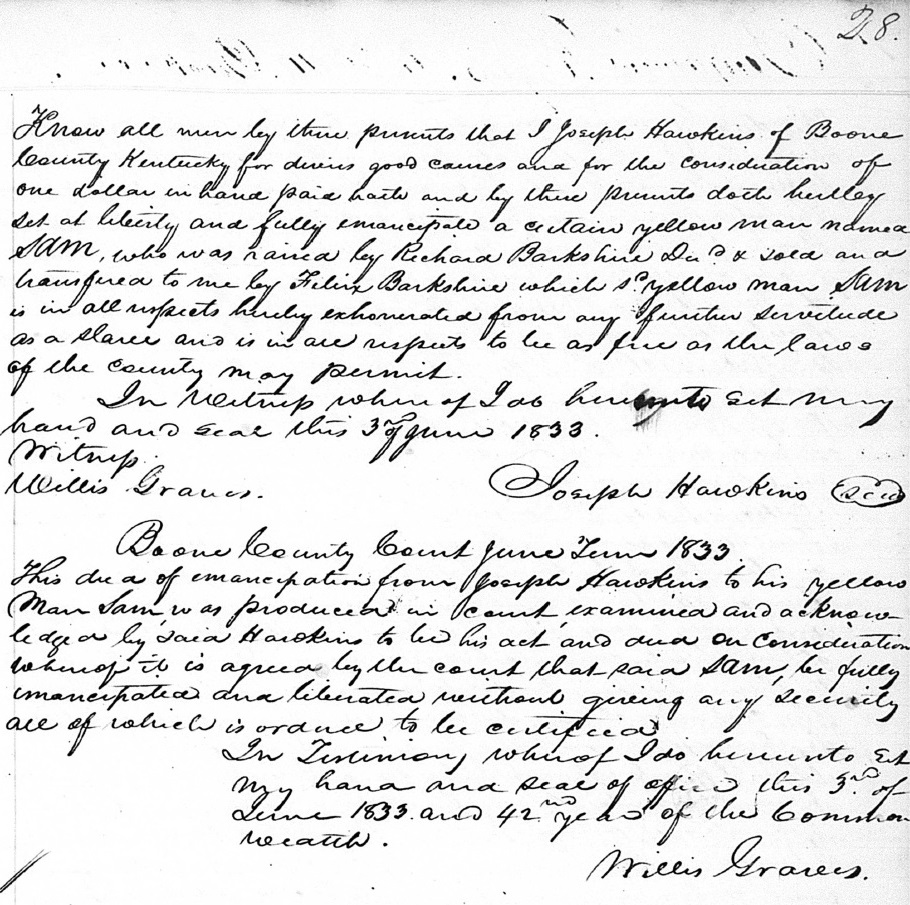

In 1833, an enslaved African American man named Samuel Barkshire received his freedom in Boone County, Kentucky, manumitted (or legally freed) by slaveholder Joseph Hawkins for the cost of one dollar. He would go on to become the patriarch of a group of Underground Railroad (UGRR) activists who helped freedom seekers along the Ohio River for over thirty years. What makes his story distinctive, is that he was joined in this cause by his family and their own former slaveholder.

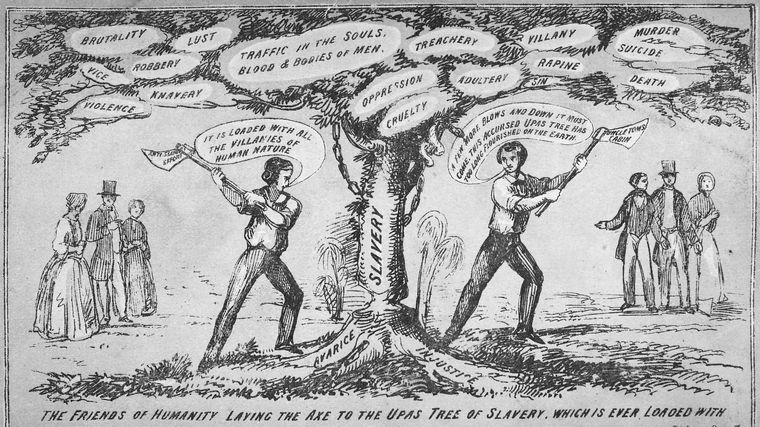

The Ohio River acted as a boundary between slavery and freedom. For nearly 40 miles, it forms the northern border of Boone County, separating it from neighbors in Indiana and Ohio. This proximity to freedom caused local slaveholders to become hyper-vigilant for signs of pending escapes. The county’s riverfront was under near-constant scrutiny of patrollers and slave hunters. In the event of an escape, the first to come under suspicion were any free African Americans living in the area. With the exception of the elderly and infirm, most formerly enslaved people left for friendlier communities immediately after manumission.

Samuel Barkshire chose to stay in Boone County, perhaps because his family was still enslaved there. He bought a 100-acre farm bordering the land of his former slaveholder, Joseph Hawkins. The land once owned by Samuel’s first slaveholder, Dickey Barkshire, was also nearby. Part of the land Samuel once owned runs along a ridgeline overlooking the Ohio River. The ridges near the river were often used by freedom seekers as safe routes leading to several crossing points from Boone County to free states. In addition to the heirs of slaveholders Joseph Hawkins and Dickey Barkshire, Samuel’s neighbors also included the Universalist Church and some of its anti-slavery members. This placement put Samuel in a position to help freedom seekers while still living in a slave state. This was a dangerous endeavor, but a strong possibility, considering his level of involvement in the UGRR in Rising Sun.

When Joseph Hawkins died in 1836, his widow Nancy was his only heir. Little is known about Nancy’s early life, but she appeared in Joseph’s life sometime around 1817, and they had no children. Hawkins’ will is a simple document; he left all of his land and property to Nancy. There was no inventory taken of the estate, but tax lists of the year of his death show he was the owner of ten enslaved people and about two hundred acres of land.

Before her marriage to Joseph, Nancy was the consort of Dickey Barkshire for a period of years following his first wife’s death. Though this relationship is referenced in her probate, no marriage document has surfaced; she may have been Dickey’s wife in name only. This connection to the Barkshires indicates she knew Samuel Barkshire for years before marrying Joseph. Nancy’s relationship with Samuel and his family was very close, so it’s likely she asked her new husband to acquire ownership of the man, in order to free him. This also may have been the case with Violet, a woman once listed as a slave of Hawkins, who was later freed. Violet and Nancy were baptized together upon joining Middle Creek Baptist Church, and lived either in the same home or nearby one another until Nancy’s death in 1854.

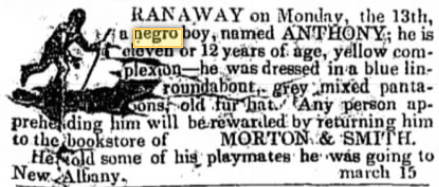

Two days after the probate of Joseph Hawkins’ estate, Nancy purchased a home in Rising Sun. The Barkshire family, Violet and several other bondsmen moved across the river at the same time. Nancy, now living in a free state, began to manumit the enslaved people she had brought from Kentucky. Nancy seemed cognizant of the dangers faced by African Americans, even those legally manumitted and living on free soil. They could be kidnapped and sold back into slavery, or bound as an indentured servant, if debt or need came into play. If the former slave was not yet of age, and had no guardian, one would be assigned by the courts, without consent of the minor. In order to avoid these pitfalls, Nancy Hawkins filed manumissions only after there was some sort of protection in place, should something happen either to her or to Samuel and his wife.

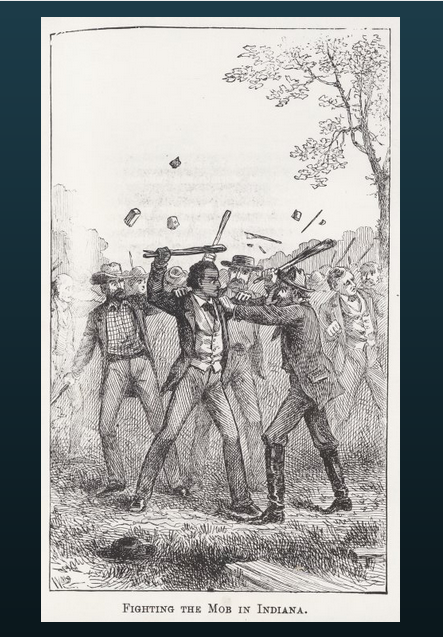

This fall marks the 180th and 170th anniversaries of two rounds of manumissions filed by Nancy Hawkins in Indiana. In August, 1838, the first group: Harriet Frances Barkshire (Samuel’s wife), a man named Sandy and Mariah Hawkins (listed together), and a woman named Catherine were manumitted by deed. All were adults, but the manumission did not get filed until after Catherine was married in Dearborn County. This is important, a single woman would have been more vulnerable than the married women in the group. The second round of manumissions was filed in September of 1848, and included the Barkshire children: Arthur, Garrett, Matilda, Emily, Woodford and Minerva. One curious detail of their manumission papers was that each person’s exact birthdate was given. At the time of their manumissions, the two eldest boys, Arthur and Garrett, were both over 21 years old, and could therefore act as guardians for the younger children if something were to happen to their parents or to Nancy Hawkins. This was no light concern, considering the involvement of the family in UGRR activity in the area.

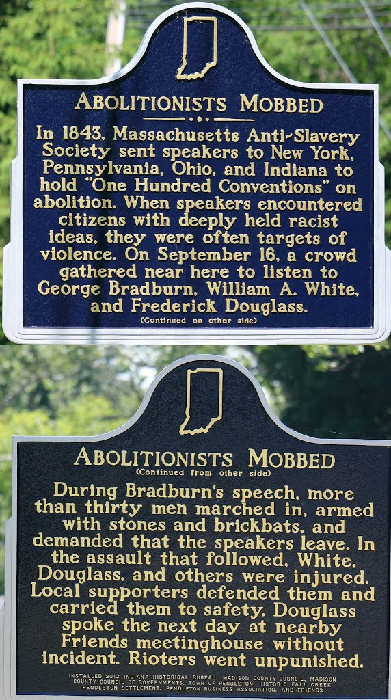

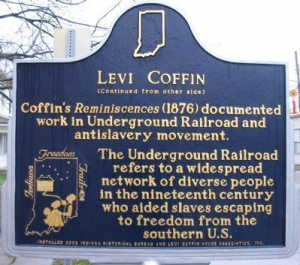

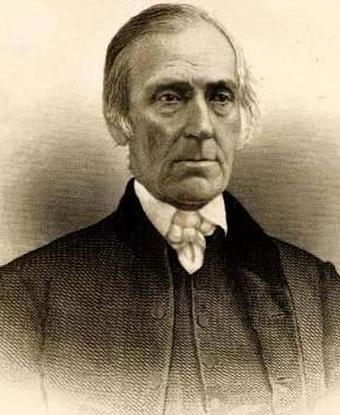

Samuel Barkshire acted as a coordinator and point of contact for Rising Sun’s UGRR network. He was well-known to local anti-slavery activists, and was acquainted with Levi Coffin, the “President of the Underground Railroad.” His participation is also mentioned in the memoirs of abolitionist Laura Smith Haviland, who sought his help in freeing a Boone County family who were enslaved in Rabbit Hash.

The three Barkshire sons acted as conductors, both on the river and over land. Their reach stretched from New Orleans all the way to Ontario, with Rising Sun serving as their base of operations. The three daughters’ involvement is not clear, but their parents and Nancy Hawkins, (with whom they sometimes lived), ran “stations” or temporary hiding places. The clandestine nature of this work would require both the help and complicity of the three girls.

Though Nancy’s involvement was not discovered during her lifetime, it was later revealed in a remembrance printed in the newspaper. As a well-heeled widow and former slaveholder herself, it was likely she wasn’t suspected by slave hunters. The author of the newspaper piece written in the 1880s, describes in great detail an episode in which five freedom seekers were kept hidden in Nancy’s home for days on end, unbeknownst to their Boone County slaveholders just across the river. It’s probable that this event was not an anomaly; she may have helped many times over.

Violet’s participation may have been comparable to that of the Barkshire daughters. She lived either with or next door to Nancy in Rising Sun over the years. Sandy Hawkins, who was freed along with Mariah, moved to New Orleans after his manumission. In 1851, he was accused of harboring a fugitive slave in his New Orleans home. Like many UGRR conductors, he also worked on riverboats, traveling from slave territory to free states regularly. Joseph Edrington, the man Catherine married in Rising Sun shortly before her manumission, was also named in Laura Smith Haviland’s memoir, as an agent of the UGRR.

The relationship between Nancy Hawkins, her friend Violet and the Barkshire family is clear in the will she left in 1854. The entirety of her household possessions were divided between the three Barkshire girls, and Violet received personal items and money. The three Barkshire sons were to share in the profit from the sale of her house, which they promptly bought back at auction. Though an unusual group, these Rising Sun activists did much to further the cause of freedom from bondage.