As you’re likely in your second or third week of social isolation, you’ve probably done everything you can think of to occupy yourself. You’ve exercised at home, binged all your favorite shows, cleaned and dusted, and reread your favorite books. What else is there to do?

Puzzles!—a longtime mainstay of home-bodied folks. Whether it’s crosswords or word searches, tabletop jigsaw puzzles or drawing games, puzzles can be a welcome pastime. These three stories from Hoosier State Chronicles, our freely-accessible digital repository of nearly a million pages of historic newspapers, will challenge your mind and warm your heart. The first item comes to us from nearly 100 years ago, in the August 28, 1920 issue of the Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram. This puzzle, known as “Pencil Twister,” was printed in the Junior Palladium section of the paper, a four-page insert published on Saturdays.

Do you think you can complete the picture? (You can view the answer here.) You would copy the object shown onto a blank piece of paper and then turn it 90-degrees counterclockwise.From there, you would attempt to complete the drawing based on a clue, which for this puzzle is “Can you change Santa into an Apricot Sundae?” I hope that you got it! This drawing puzzle is a bit different than most of your average brain games.

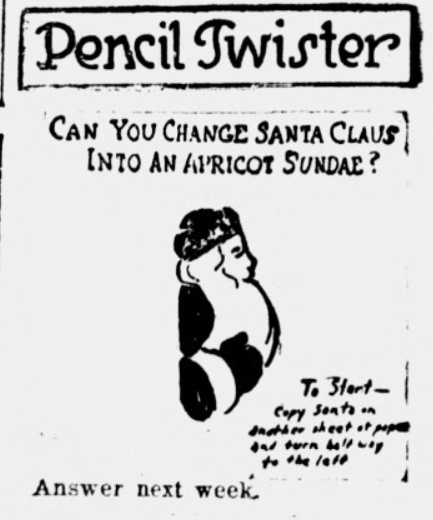

Next up is an inspiring story from the October 29, 1983 issue of the Indianapolis Recorder. It centers on the life of Bertie Miller, a retired nurse’s aide and secretary who devoted her golden years to jigsaw puzzles—using only one hand to complete them. Years before, Miller lost her right hand to an amputation following a stroke, but that didn’t stop her. Her passion for puzzles started around that time, when her friend asked her to help finish one. “By having use of only one hand,” Miller shared, “I didn’t think I would be much help—I looked past my handicap and helped her.” After that, she was hooked. Over the next seven years, she completed roughly 200 jigsaw puzzles, many of which she had framed for display in her room at the Central Healthcare Center where she lived. She even won a blue-ribbon award at the Indianapolis Black Expo for one of her puzzles.

Alongside her jigsaw joys, Miller kept herself busy with distributing mail to her fellow residents at the Central Healthcare Center, playing bingo, chatting with other residents who were room bound, and attending church. She was also a grandmother to seven and great grandmother to another seven, all of whom she would regularly visit with. The Recorder called her a “truly remarkable and independent lady.”

Mary Jane Allen, activity director for the center, remarked on Miller’s love for puzzle craft. “Among Mrs. Miller’s favorite puzzles to work have been The Lord’s Supper, the Changing of the Guards, animals, flowers, antique cars and a large puzzle of kinds of jellybean candies.” Allen also reflected on how this hobby improved Miller’s life for the better. “She has rehabilitated herself with this hobby and is learning to use her good hand,” Allen said. Miller loved sharing her hobby with others; her completed puzzles adorned the walls of the center and were given to fellow residents as gifts. Bertie Miller “hasn’t let her handicap prevent her from living and [bringing] happiness to others,” the Recorder noted. During your time at home, dust off your puzzles and finish one in Bertie’s honor.

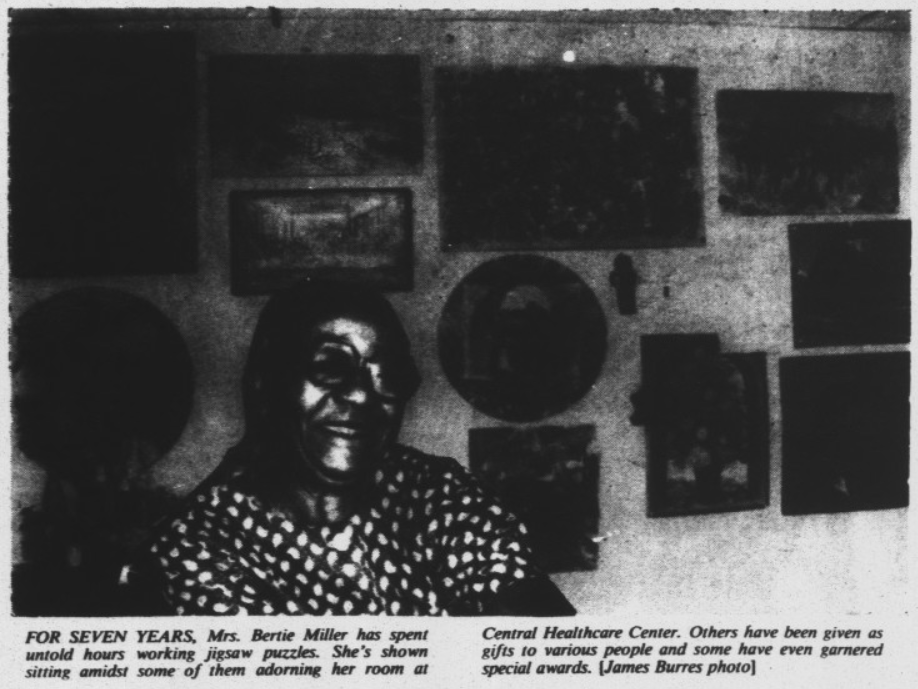

Our final story comes from a May 4, 2001 article in the Indianapolis Recorder that also reports on jigsaw puzzles but focuses this time on their educational value. W. Bruce Adams, an entrepreneur who worked as a salesman for iconic game company Parker Brothers, started his own venture creating African American history themed jigsaw puzzles. “I couldn’t believe that 10 years after I left Parker Brothers there were still no puzzles with African-American themed images on them,” he said. This inspired Adams to develop his own line of African American themed puzzles. “I looked all over and couldn’t find any,” he remembered. “I said ‘this is a perfect opportunity for me to start a business, doing something no one else is doing.’”

Adams’s passion for culturally-relevant products may have started when he worked as an intern for the trailblazing congresswoman and presidential candidate, Shirley Chisholm. Realizing law wasn’t for him during his work with Chisholm, Adams found his calling in sales and worked for Parker Brothers, as well as Gabriel Toys and Bristol-Myers. It was at Parker Brothers that he first discovered there were no African American themed games, so he started developing prototypes in his spare time that he sold at flea markets, yard sales, and trade fairs.

Adams began his own game company around 1998, with his first two puzzles centered around African American history. The first, “Portrait of African American History,” highlighted important figures such as Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The puzzle “The Dream, Martin Luther King, Jr.” focused exclusively on the civil rights leader and orator. Later, he created puzzles focusing on Kwanzaa and Kenyan culture. Adams developed these puzzles and others with African American artists, such as Brenda Joysmith, Synthia St. James, Charles Bibbs, and Paul Goodnight. His roster grew to 20 puzzles by 2001.

Customers at flea markets and trade shows were thrilled with Adams’s puzzles, citing their educational value. Adams recalled:

When I was doing flea markets, African American parents would always come up to me and ask, ‘Do you have any African-American educational puzzles?’ Puzzles are very educational because they teach eye hand coordination skills, they help your memory, and I noticed that a lot of African Americans bought puzzles.

His success with the company led to retailers like Walmart and Toys “R” Us carrying his products, which sometimes sold out too quickly for his small sales staff to keep up with. In an effort to meet demand, the company used telemarketing and the internet to get the word out about his puzzles.

Alongside puzzles, Adams developed educational CD-ROM games with Lady Sala Shabazz, a nationally-syndicated radio host and independent children’s book author. He also developed puzzles with food entrepreneur and television personality Wally “Famous” Amos. Adams’s dedication to fun games with a message should encourage you to take advantage of the time you have at home, to perhaps finish a puzzle with a historical or educational theme. If you have kids, bring them in on the fun!

We hope these stories of puzzles, games, and community have helped uplift you. It’s through all of our actions that we can extend our sense of Hoosier kindness to ourselves and others. Now, get to puzzling!

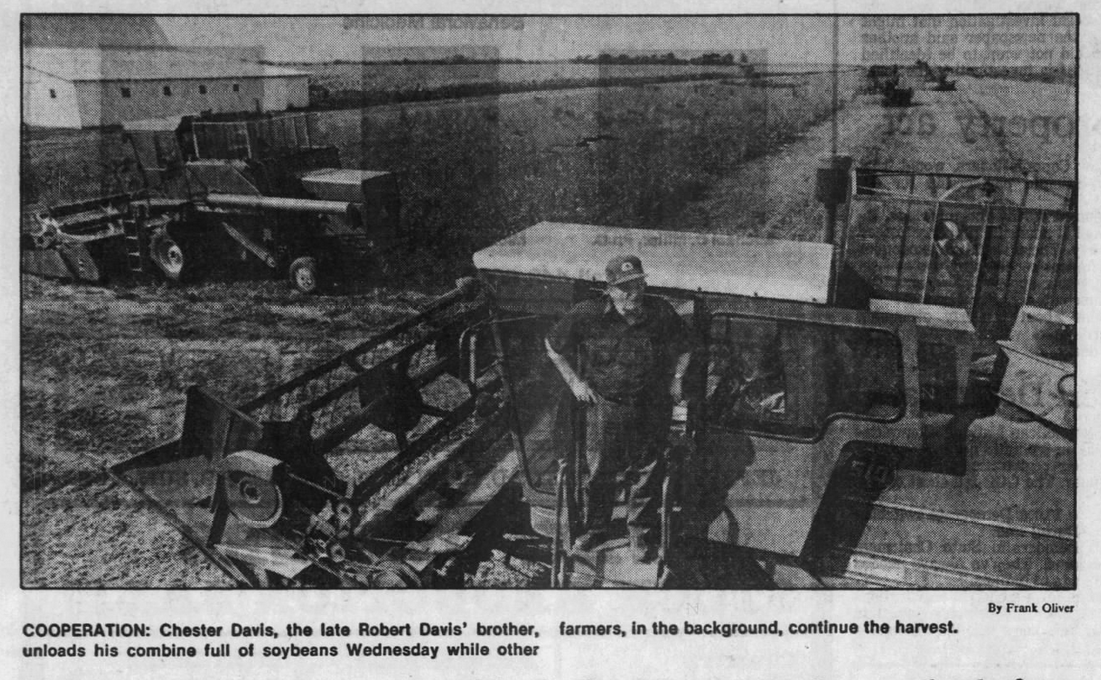

One of the farmers, Robert Akers, told the local newspaper simply, “This is just the way the community works.” The neighbor who organized the harvest, Ralph Reed, echoed the sentiment, stating: “It’s just a job that has to be done.” Reed explained that this community effort was their “own kind of insurance.” Robert’s brother Clive teared up when he told the local reporter:

One of the farmers, Robert Akers, told the local newspaper simply, “This is just the way the community works.” The neighbor who organized the harvest, Ralph Reed, echoed the sentiment, stating: “It’s just a job that has to be done.” Reed explained that this community effort was their “own kind of insurance.” Robert’s brother Clive teared up when he told the local reporter: