Guzzler’s Gin, Dunking Donuts, “I dood it!:” Red Skelton’s iconic characters and quips would not exist without the influence of his first wife Edna Stillwell. In fact, a Rochester, NY newspaper reported that Skelton insisted “he’d be a bum” without her. Through Stillwell’s comedic and management muscle, Skelton went from an unknown circus performer to one of the most lauded comedians in television and film history.

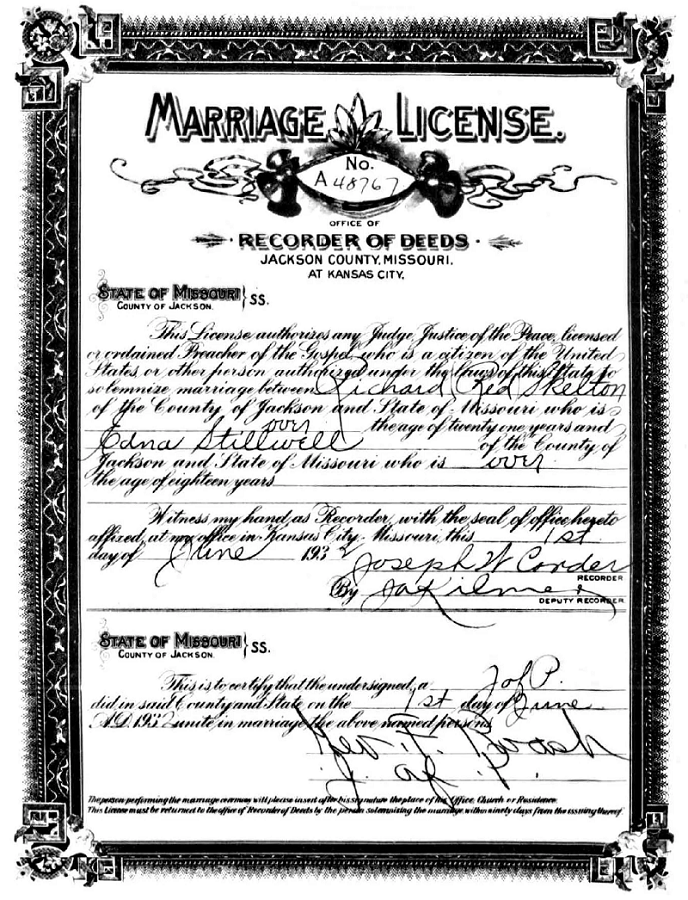

Stillwell was born in Missouri on May 25, 1915. As a teenager she was attracted to show business and the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle reported that she was head usherette at Pantages Theatre in Kansas City, where seventeen-year-old Skelton performed. Skelton recalled that she took an immediate disliking to him. At his next job, he served as master of ceremonies at a walkathon, where Stillwell happened to be working as cashier. He eventually convinced her to go on a date with him. Skelton cemented her affections when he chose her to kiss in a photoshoot. He recalled “‘I grabbed her and kissed her and it made me dizzy. This was it. This was love. I guess we both were dizzy. We got married.'”

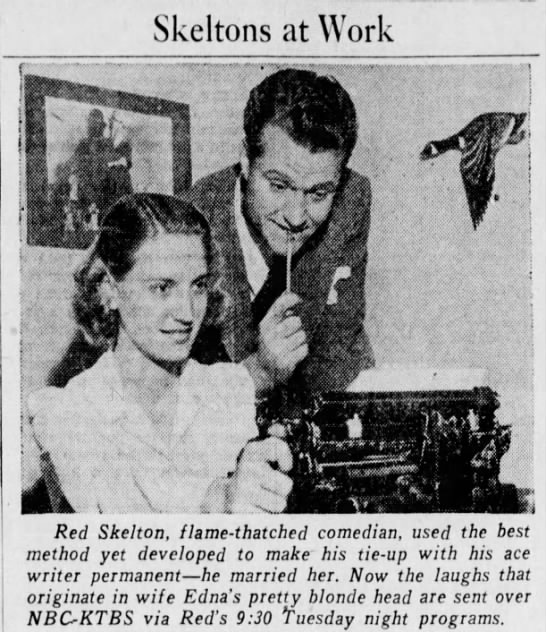

The entertainer, at the time, was so poor that Stillwell had to pay for their marriage license. After the wedding she assumed the role of business manager, a duty she would continue to fill even after their 1944 divorce. According to the Democrat and Chronicle, the manager of a walkathon in St. Louis wanted to cut Skelton’s salary, prompting Stillwell to approach him and successfully demand more money. Skelton noted, “‘I told her I’d handle my own affairs. Only she shut me up with the news that I’d get $100 a week. She also tossed the boss into doing my dry cleaning.'” She eventually negotiated his walkathon pay up to $500 per week and invested his money in real estate. She also forced Skelton, a high school drop-out, to study and earn his high school degree. He admitted “‘pretty soon I didn’t feel like such a fool when I was in a room full of people talking about something besides burlesque.'”

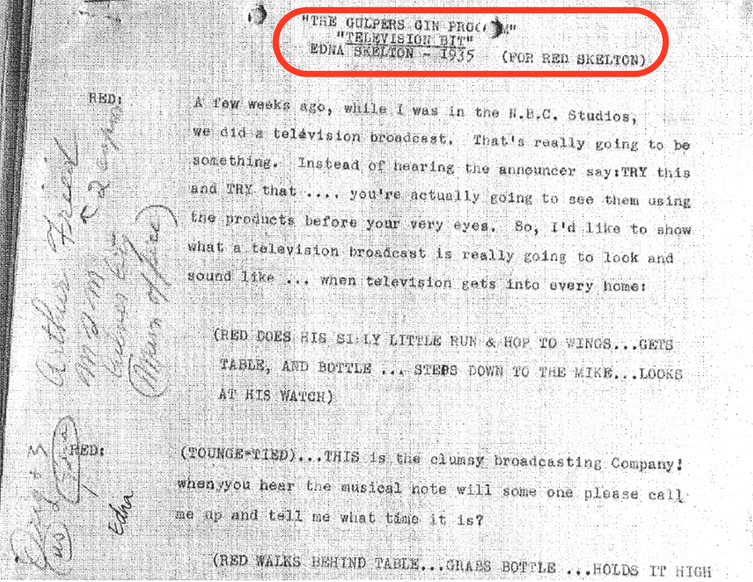

Stillwell was just as formidable when it came to comedy writing. According to the Indianapolis Star, Skelton’s vaudeville run in Montreal was nearly cancelled after his first performance, so:

Red went back to his own individual style, which had put him over in vaudeville. And his wife in a moment of contempt for the old routines they were doing, said, ‘I could write better stuff than that,’ Red’s answer was “Why don’t you?’ also in sarcasm. But she did, and she has written his material ever since.

In a 1941 article, The Tennessean observed that “from several years of watching what tripe came down the pike on the old Pan circuit, Edna got some pretty definite ideas about what to avoid in a vaudeville skit.”

A newspaper piece by Ted Gill noted that soon after marrying, Stillwell dreamed up Skelton’s famous “Junior” character. When the couple strolled past stores Red could never “resist the urge to buy things” and if “Edna attempted to talk him out of it, he’d lie down on the sidewalk, kick his heels and make such a scene that he soon had scores of passersby in near-convulsions.” From then on Stillwell considered herself “Mommie” to his “Junior.” According to a 1942 Indianapolis Star article, Stillwell’s “Junior” sketch catapulted Skelton’s career forward and as she “schemed out that screamingly funny little boy burlesque-topped off by those three precious words, ‘I dood it!’-the name of Skelton fairly leaped from the bottom to the top of various radio comedian polls.” The article also mentioned that she helped mastermind Skelton’s “$50,000 doughnut dunking act,” after the couple dined at a Montreal cafe. The article stated that Stillwell and Skelton,

then playing together in small-time vaudeville, watched a diner as he slyly held his hat over his hand while he dunked, furtively looked around and then popped the soaked sinker into his mouth. The Skeltons doped out the outline of the act before they left the restaurant, polished it up in their hotel room that afternoon and presented it the same evening at the theater. It was an instantaneous hit and established Skelton as a top-line variety performer.

Writing material and coaching her husband from theater wings proved to be the steady hand Skelton needed to succeed in his career. Skelton’s biographer Wes Gehring contended that “Stillwell’s mid-1930s donut routine and other reality-based writing helped Skelton segue his skills into vaudeville, the next rung on the entertainment ladder.” He noted that “Working, performing, and traveling together as nomadic vaudevillians in the 1930s, the Skeltons were a team to reckon with.” By the late 1930s, the couple moved to Hollywood, where Skelton earned a notable $2,000 for appearing in the film Having Wonderful Time, alongside Ginger Rogers and Douglas Fairbanks Jr.

In order to make money between films Skelton returned to the stage. Stillwell demanded he refuse any offer under $1,000, causing them to go without food for days. But staying the course paid off, as the Democrat and Chronicle reported, because Skelton “got a coast-to-coast radio program and soon he was clicking in vaudeville-and at Edna’s price.” Stillwell wrote for and appeared on Skelton’s popular radio show and had performed with him on Rudy Vallee‘s program. His national NBC show (featuring renowned radio and television pair Ozzie and Harriet Nelson), in tandem with his film Whistling in the Dark, catapulted Skelton to national fame in 1941. Gehring concluded that Stillwell also had a hand in his film success, stating that “True to Stillwell’s good instincts for her husband, she was the first to recognize just how effective he would be” in Whistling. The Indianapolis Star informed readers that year that “At his disposal at present are some 500 comedy routines all written by himself or his wife, with which he has been throwing Hollywood audiences, both on and off the screen, into hysterics.”

At the end of 1942, newspapers across the country announced that Stillwell had filed for divorce from her partner in comedy. The Dixon [Illinois] Evening Telegraph noted that she filed suit, “charging cruelty, but plans to continue to write the wit that has made his radio act famous,” which she did after the court finalized the divorce. The former couple even performed their original vaudeville routines at army camp shows in WWII to popular reception. Their professional relationship continued until 1952, one year after Skelton was given his own, groundbreaking television show. Gehring contended that their post-divorce work was “a mixed bag-a rousing success professionally, but a stressful distraction for each of their subsequent marriages.” Skelton married actress Georgia Maureen Davis and Stillwell married Hollywood film director Frank Borzage, who had directed Skelton in films like Flight Command.

Stillwell died in Los Angeles on November 15, 1982. Without “Mommie’s” aptitude and intuition, Skelton likely would never have “dood it!” Learn more about the funny man with our newest historical marker, located in Vincennes.