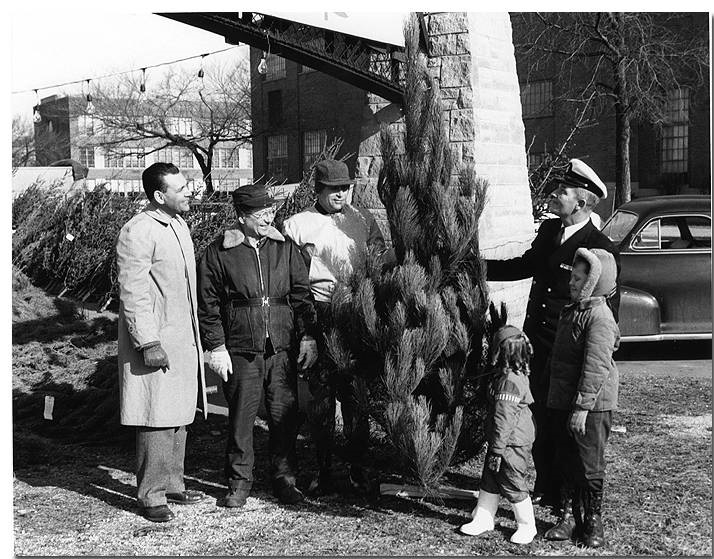

In 1950, the Indianapolis Star asked its readers “Is your Christmas tree a Hoosier, too?” Turns out, there was a good chance it was. The article reported that by December 17, 1950, Indiana State Forests and private growers had already cut 100,000 pine trees for the Christmas season. How did the state get into the Christmas tree business?

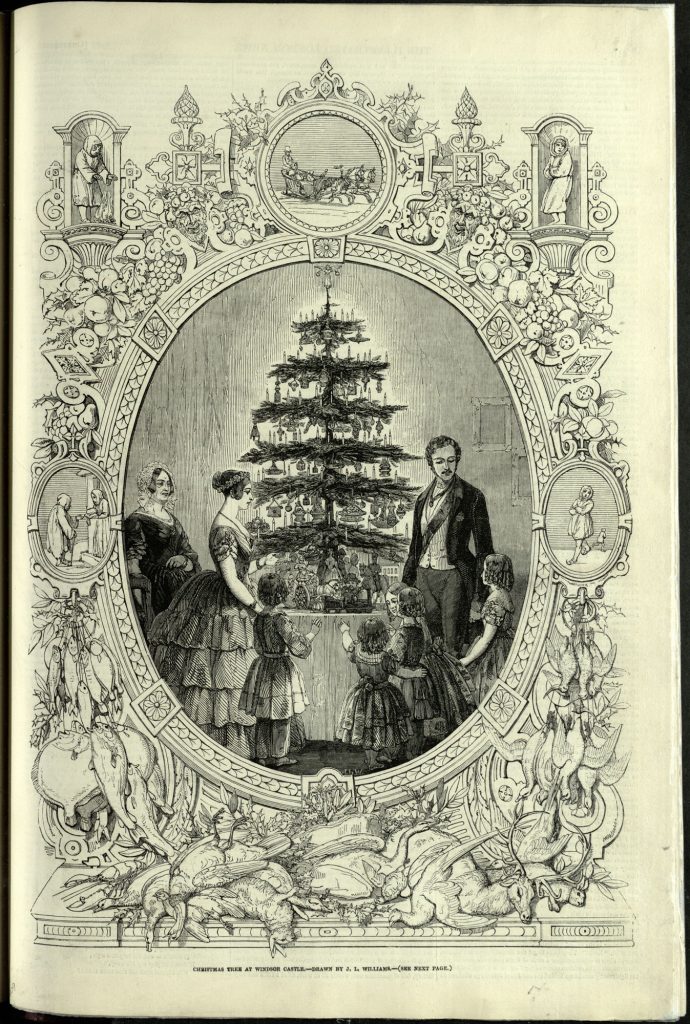

German immigrants brought the Christmas tree tradition to America in the 1700s. However, the practice didn’t catch on for the rest of the nation until the mid-19th century when England’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, popularized it. In 1848, an illustration of the royal family celebrating around a Christmas tree appeared in the Illustrated London News. Eventually, putting up a Christmas tree spread from Britain to the United States as individuals sought to emulate the fashionable royal family.

By the time Christmas trees became a relatively common American tradition, American forests were dwindling, including in Indiana. European-American settlers had cleared much of Indiana’s original 20 million acres of forests for farming, fuel, and lumber by the mid-1800s. As forests disappeared, Americans began to realize the natural resources in their vast country were not inexhaustible. A new conservation ethic emerged, which championed rational use and planning of natural resources, including forests so enough lumber (and of course, Christmas trees) would be available for future generations.

For some, the new conservation ethic clashed with the Christmas tree tradition. How could conservationists approve chopping down hundreds of thousands of trees every December for the holiday festivities? According to legend, President Theodore Roosevelt, an ardent conservationist, refused to have a Christmas tree in the White House because he was opposed to excessive lumbering practices. During his presidency, journalists speculated in newspapers whether the Roosevelt family would put up a tree. According to some accounts, in 1902, Roosevelt forbade his family to have a Christmas tree. In retaliation, Roosevelt’s son, Archie hid a tree in a closet, had a White House electrician hang some lights on it, and surprised his family with it on Christmas Day.

Hoosiers too were conflicted between their new commitment to conservation and love of holiday festivities. The first advertisements for Christmas trees for sale appeared in Indiana newspapers around the 1860s. At the same time, Christmas parties or festivals for children, all featuring Christmas trees and gift giving, began to be held.

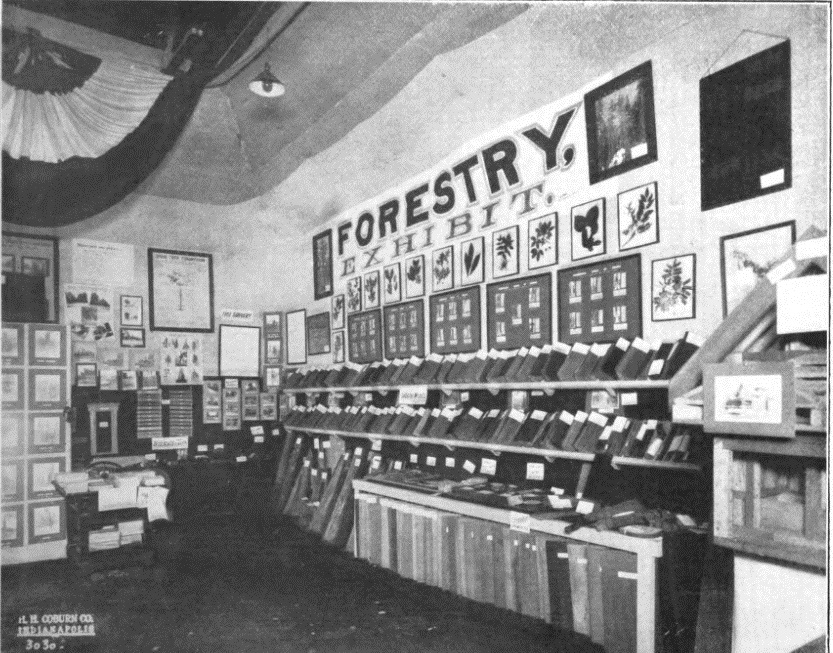

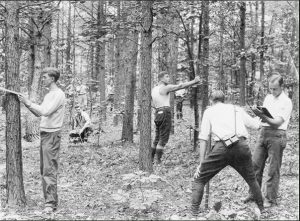

On the other hand, Indiana started its state forestry program in 1901 and established the state’s first forest reservation in Clark County, later known as the Clark State Forest, in 1903. The state began experimental plantings at the state forest in 1904 to determine the trees best suited to Indiana soils and thus reforest the state.

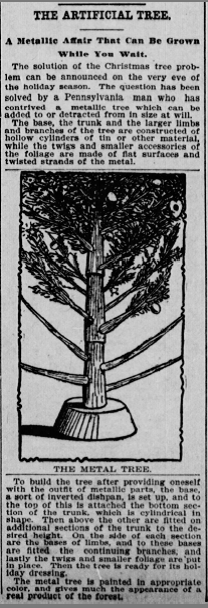

As state foresters slowly repopulated the state with trees, Hoosiers debated whether they could be conservationists, without also being a Scrooge. James S. Whipple, state forest, fish, and game commissioner issued a statement in 1907 encouraging families to use artificial trees instead of cutting down young evergreen trees for the holidays. Whipple said “To destroy millions of these trees every year when we are in such need of more timber in this country . . . seems very wasteful.”

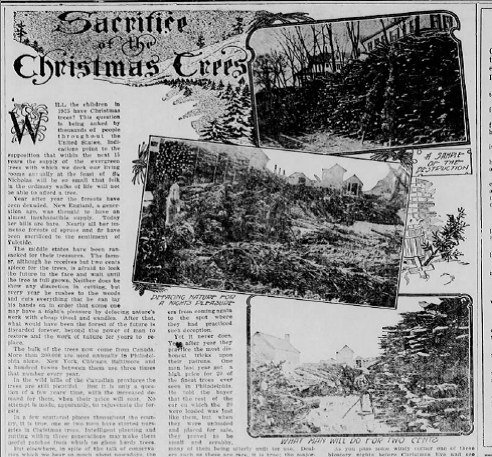

In 1911, the Angola Herald of Angola, Indiana printed an article titled “Sacrifice of the Christmas Trees,” complete with several photos of logging operations. One photo of a pile of freshly cut pines next to trucks laden with logs was captioned “Defacing Nature for a Night’s Pleasure.” The article asked “Will the children in 1925 have Christmas trees? . . . Indications point to the supposition that within the next 15 years the supply of the evergreen trees with which we deck our living rooms annually at the feast of St. Nicholas will be so small that folk in ordinary walks of life will not be able to afford a tree.” The article noted that trees were so scarce on the east coast and Midwest, most Christmas trees had to be imported from Canada.

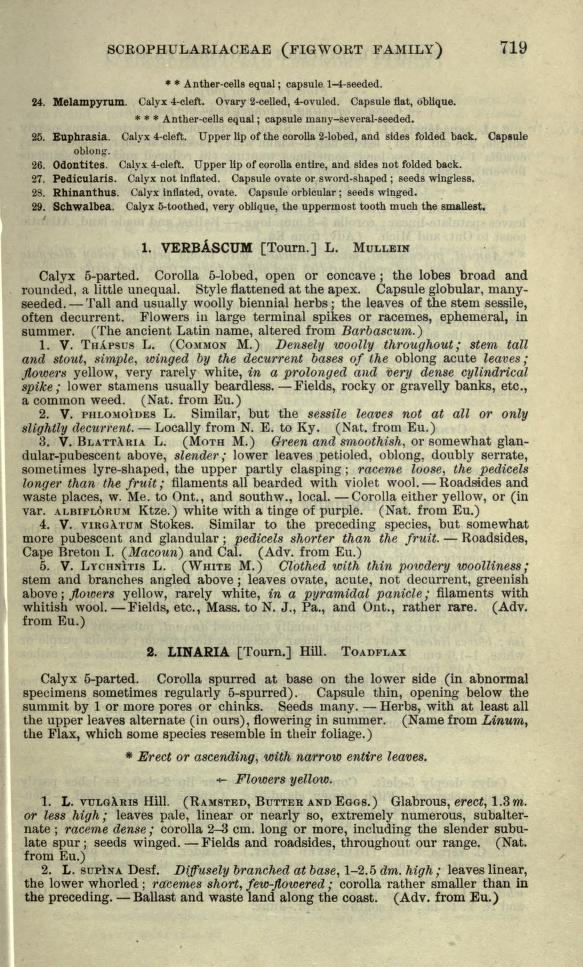

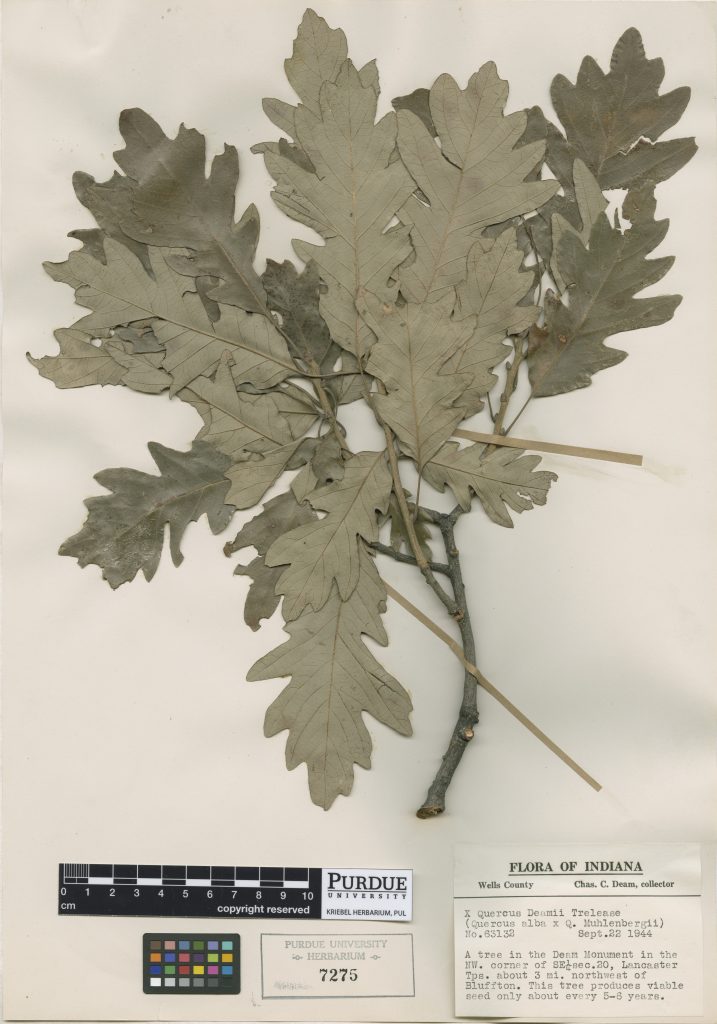

Luckily, most Hoosier conservationists recognized the beloved Christmas tree could be used to advance forestry in the state. Frank N. Wallace, the state entomologist, frankly told the Indianapolis News in 1924 “Let’s have Christmas trees.” Wallace said he believed the Christmas tree custom “can be utilized as a boom to forestation, for the American Christmas traditions are built around the tree and in order that future generations may have the privileges of the present generation,” the present generation must support reforestation. The next year, esteemed botanist and state forester Charles C. Deam encouraged the local communities to begin growing enough Christmas trees to satisfy local demand. Deam noted that large waste lands unsuitable for agriculture all over Indiana could be used to grow common Christmas tree varieties, including Norway spruce, white spruce, balsam fir, and Douglas fir. Since prices on imported fir and spruce had increased that year by 30%, Christmas tree farming could be quite profitable for the Hoosier economy.

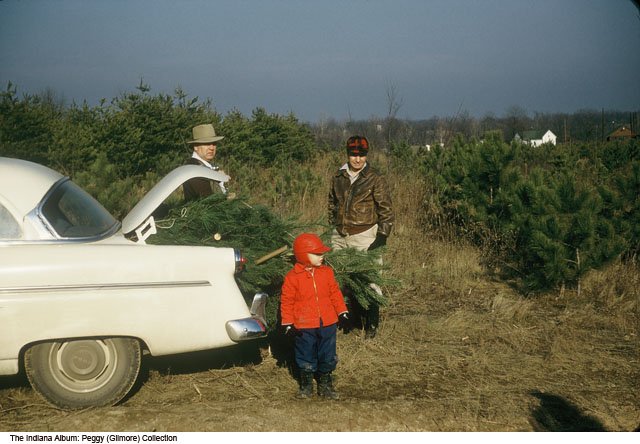

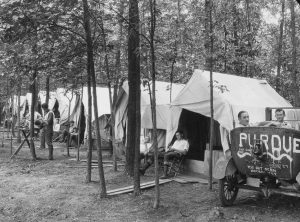

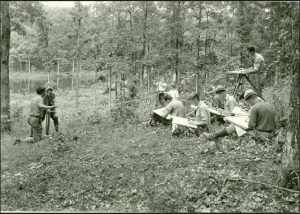

Christmas tree farms began to spread across the state, especially after World War II. State foresters provided guidance on forestry management, tree trimming and cutting. Farmers could jumpstart their Christmas tree farm by purchasing and planting pine seedlings nurtured at one of several state forests. However, farmers had to be dedicated; growing a Christmas tree was time consuming. In 1964, Outdoor Indiana featured the Bob Kern Christmas Tree Farm in Fulton County, Indiana. Kern established his farm in about 1947. He managed 400 acres of Scotch and white pine, as well as other species of spruce and fir. Kern emphasized Christmas tree growing was so difficult because farmers had to pay particular attention to cultivating richly colored, symmetrical trees that consumers would want in their homes. Weeds had to kept down and each tree pruned to its desired taper. Furthermore, a six foot tree generally took at least six years to grow. Since it took so much time to produce just one tree, seedlings had to be planted soon after a tree was cut to replace it.

While Christmas trees survived the conservation era, similar doubts arose in the 1970s during the environmental movement. Postwar affluence fueled by factories, cars, and consumer goods resulted in increasingly polluted water, air, and land. Growing numbers of people, including Hoosiers, lobbied for stronger environmental legislation and adopted new practices, like recycling, to reduce their impact on their natural surroundings. Some still worried cutting down trees for the holidays had a detrimental impact on the environment.

EJ Lott, Purdue University Extension forester assured environmentalists in 1972 that for every tree cut, two or three more were planted the next spring to replace it. He emphasized that “an acre of growing Christmas trees will produce daily oxygen requirements for 18 people.” Furthermore, tree plantations provided not only aesthetically pleasing landscapes, but quality habitats for wildlife. In reality, Christmas trees were a crop, just like soybeans or corn. As long as consumers bought trees, Christmas tree farmers would plant even more to replace those they harvested. As the Herald of Jasper Indiana noted succinctly,

If there was no market for Christmas trees, growers would not plant them. Enjoy your tree.

Environmentalists also attempted to halt the tendency to burn or throw out Christmas trees once the holidays were over. Various groups in Indiana began fitting Christmas trees into the new “reduce, reuse, recycle” attitude. In Anderson, Indiana, the League of Women Voters started a tree recycling program in 1972. Instead of throwing out old Christmas trees, they would be chopped up into chips for mulch that could be used later in landscaping and gardening. The Anderson Daily Bulletin noted that “by recycling these trees, we’re not wasting a valuable natural resource and actually are saving taxpayers’ money by not using up much-needed space in the city landfill.” To raise awareness, League of Women Voters members put tags on Christmas trees for sale that asked future owners to recycle the tree once the Christmas season was over. In 1973, the group reported that they had recycled over 700 trees. In a letter to the editor featured in the Anderson Daily Bulletin, the co-chairman of the group wrote “While other cities were still burning trees, Anderson was taking a step forward in ecology.” Other organizations encouraged the purchase of living Christmas trees that one could replant in a park or their backyard after the holiday season was over.