In the latter days of the summer of 1904, the decision of a local doctor and postmaster caused an uproar in Ferdinand, Indiana and even caught attention across the country. “People in the vicinity of Ferdinand do not like the action of the postmaster and are loud in condemning him,” wrote the Evansville Courier. The Fort Wayne Sentinel noted that “threats have been made to burn the doctor in effigy and boycott his office.” The Paris, Kentucky-based Bourbon News wrote that a “storm is raging among the white people” of Ferdinand after the appointment. The Nebraska City, Nebraska Daily Tribune noted that the public were “excited over” the decision.

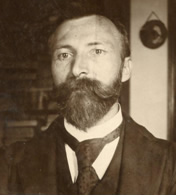

What could have caused all this furor? Dr. Alois Wollenmann, pharmacist and postmaster of Ferdinand appointed 16-year-old Ida P. Hagan to the position of deputy postmaster. While her age might have been controversial enough, there was one particular detail about Hagan which might have been more important: she was a Black woman. Wollenmann, a Republican in an almost exclusively Democratic area, with mostly Democratic public officials, made the bold and courageous decision to appoint a Black young woman to be his assistant, at a time when racial terror lynchings were regular occurrences and Jim Crow was bifurcating the country. He stuck by his decision, saying that it was “his own business” whom he appointed as his assistant and she would “remain as assistant as long as he is postmaster in Ferdinand.”

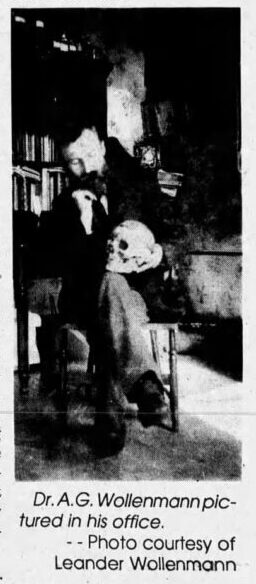

This decision represented the character of Alois Wollenmann, a Swiss immigrant who chose Ferdinand as his home and, through Hagan’s appointment, moved said home in the direction of racial equality. A skilled and versatile physician, Wollenmann routinely published articles on a wide array of topics, many on improving the lives of children. He served as Ferdinand’s dedicated postmaster for nearly fifteen years, winning the trust and support of the community. Wollenmann’s contributions to Ferdinand stand as examples of courage and commitment to community that still resonate with his adopted home.

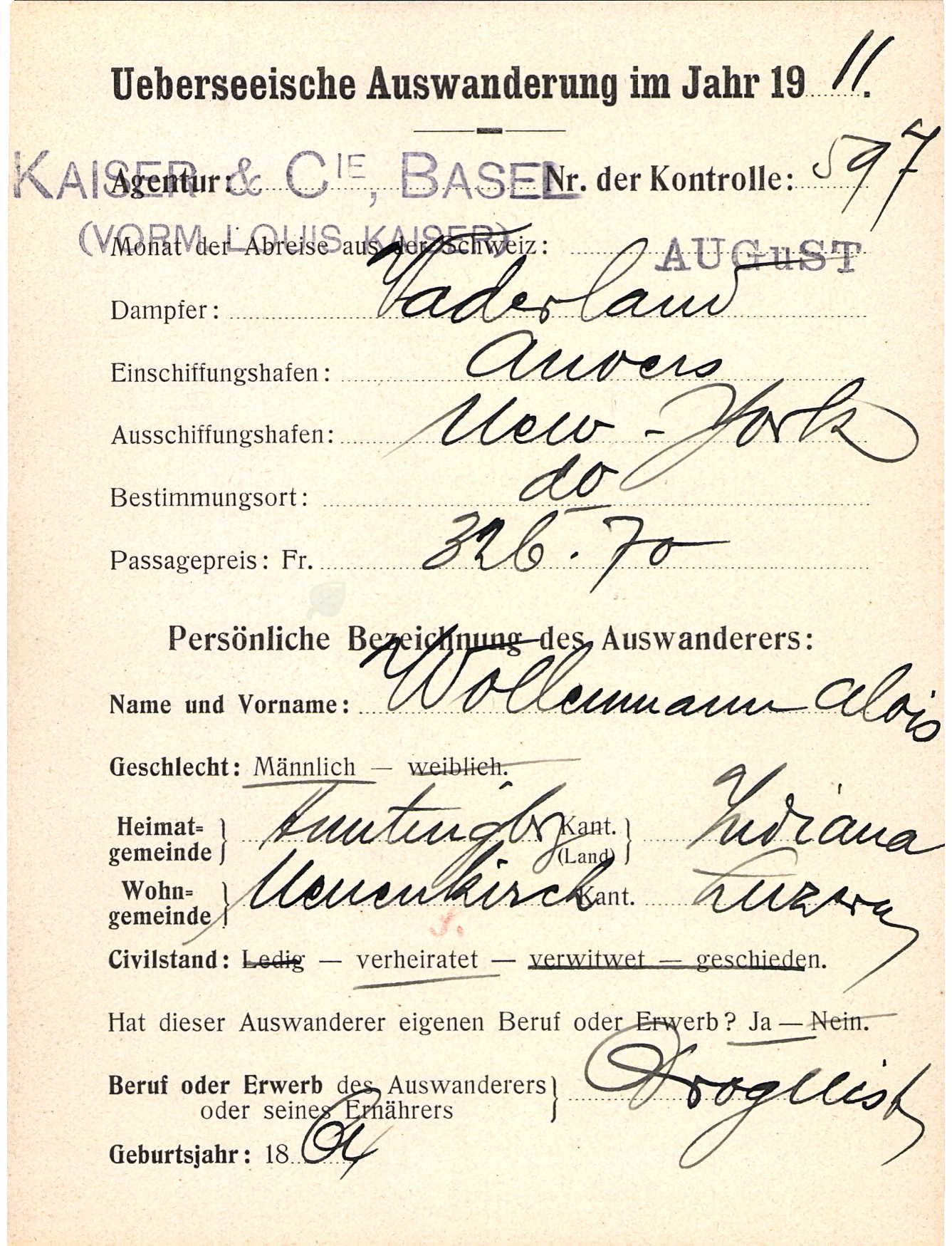

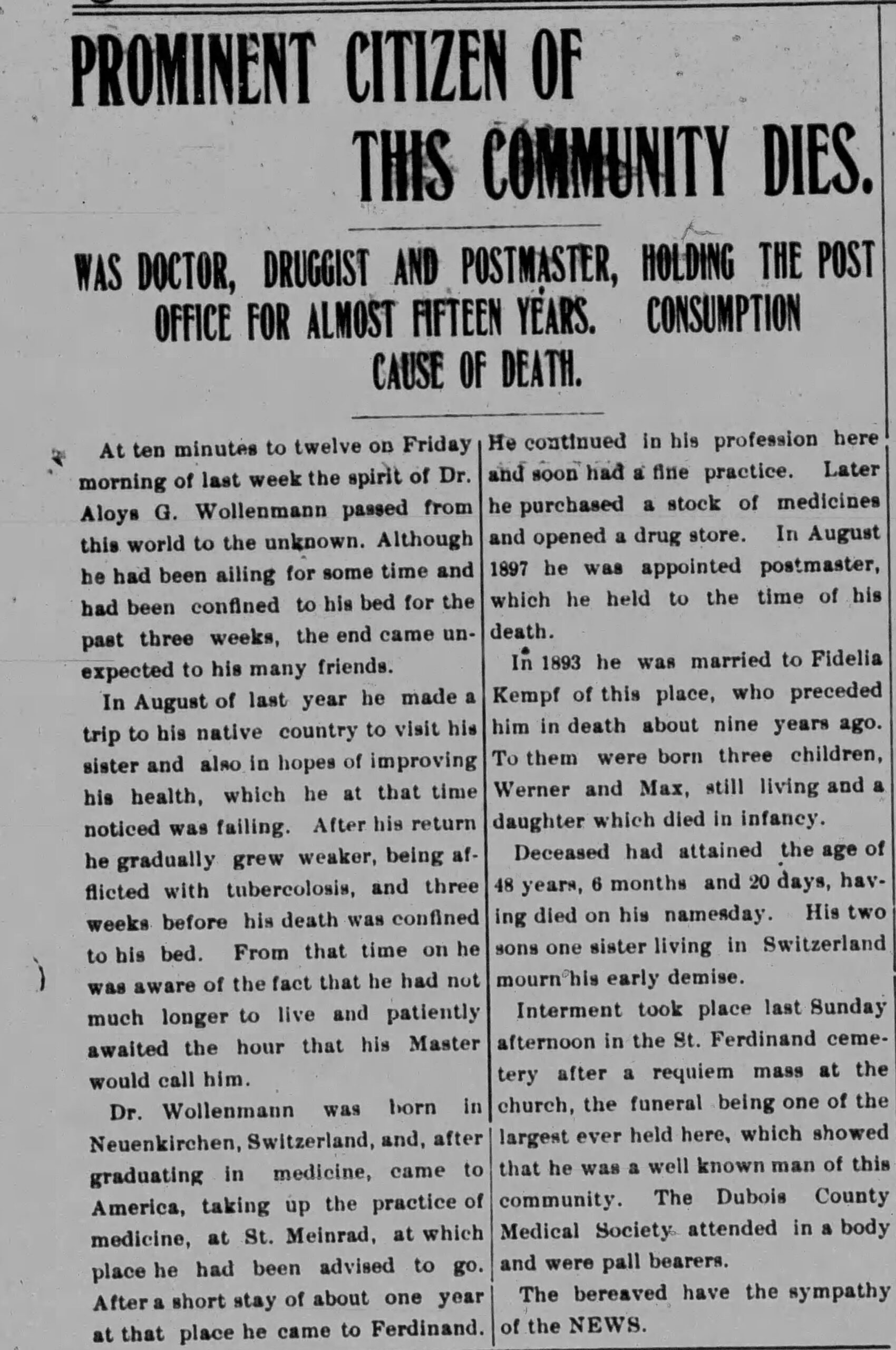

Alois Wollenmann was born in 1864 in Neuenkirch, Switzerland, to Anton and Agatha Wollenmann. While sources provide us little about his life pre-immigration, we know that Wollenmann graduated from the University of Munich in 1889, likely in medicine. He emigrated to the United States shortly thereafter, according to the United States Census. He first settled in the town of St. Meinrad, Indiana, practicing medicine there, as well as learning English at the local seminary, which had been founded by a Swiss monk. His grandson, Leander Wollenmann, claimed that he also pursued additional medical training at the University of Kentucky School of Medicine.

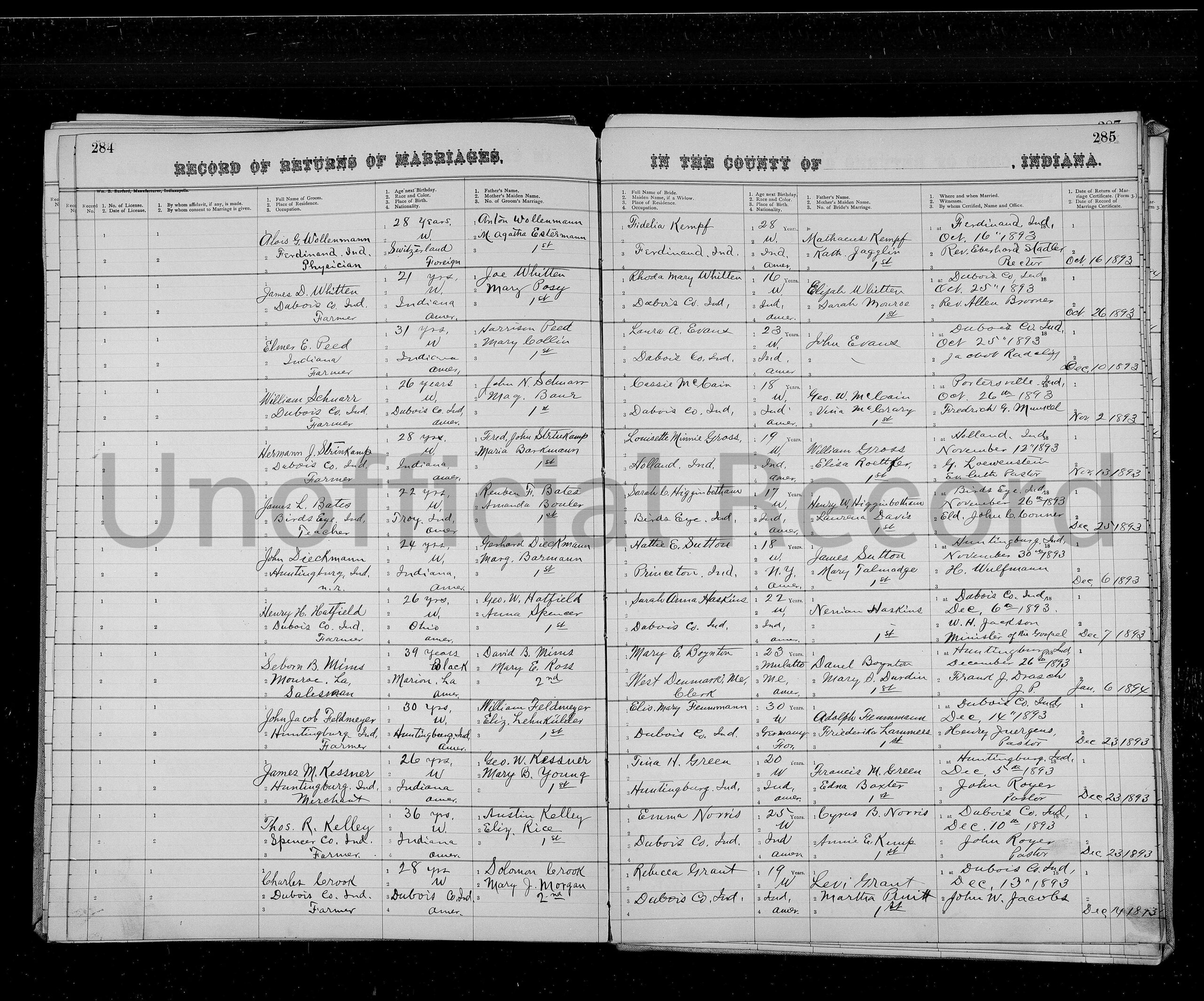

He stayed there for a year before moving to Ferdinand in 1893, where he married Fidelia Kempf, the daughter of a medical professor who coincidentally taught at the University of Kentucky,. That October, the Kempfs sold four lots of land to the Wollenmanns in Ferdinand, as noted by the Jasper Weekly Courier, and both families remained cordial for years. Wollenmann fathered two sons, Werner and Max, as well as a daughter, Mary Margaret.

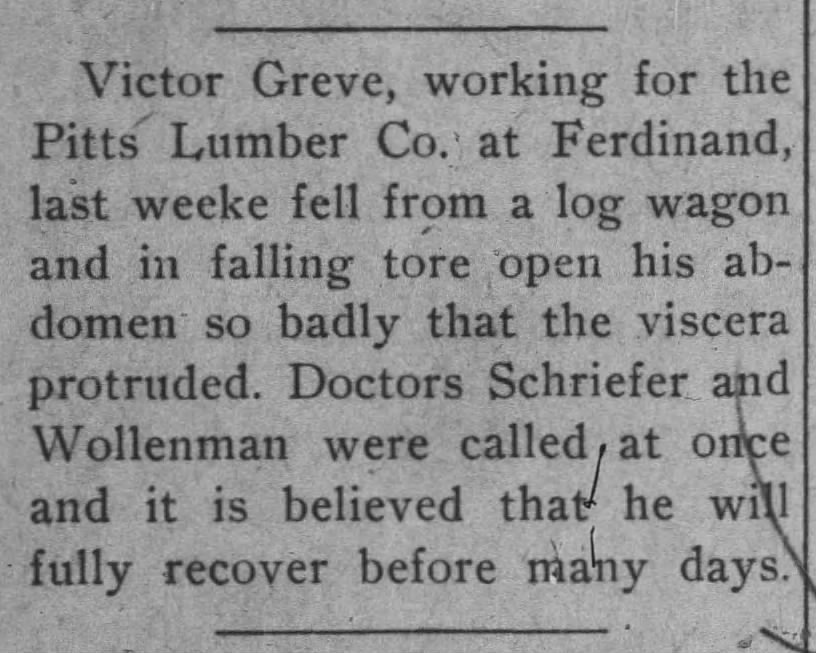

Within a few years, Wollenmann received his state medical license and started providing medical services, including for impoverished residents, in Dubois County, where he was also a member of its medical society.[i] Wollenmann also provided the county with guidance on inquests for the mentally ill. In 1903, he assisted another doctor in deeming a young woman insane, fulfilling requirements for her transfer to the asylum in Evansville. He also provided life-saving care to accident victims like Victor Greve. An employee of the Pitts Lumber Company in Ferdinand, Greve “fell from a log wagon and in falling tore open his abdomen so badly that the viscera protruded.” Dr. Wollenmann and another doctor “were called at once and it is believed that he will fully recover before many days.”[ii] Another example of life-saving care from Wollenmann came in 1909, when Gerhard Hoefels, ravenously hungry, swallowed “a chunk of meat” and “nearly choked to death when Dr. Wollenman [sic] arrived and relived him of his suffering.” From assisting the mentally ill to saving people from asphyxiation, Dr. Alois Wollenmann always lent a helping hand.

In 1892, Dr. Wollenmann “purchased a stock of medicines and opened a drug store,” known to its patrons as the Adler Apothak, or the “Eagle Pharmacy.” Here, he sold his own medicines as well as products from other practitioners like Lena Hug, who created a “rheumatism cure” and a “huge hair tonic.” Alongside medicines, he also provided eyecare services. “Are you in need of a pair of Eyeglasses?,” a notice declared in the July 9, 1909 edition of the Ferdinand News, “Well, then go to the Drug Store and have a pair correctly fitted by Dr. A. G. Wollenmann.”

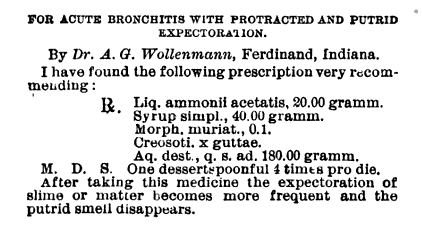

When he wasn’t practicing medicine, Dr. Wollenmann wrote about it extensively. Numerous articles by him appeared in both English and German language journals, showcasing his wide talents as a physician. His 1895 contributions to Der praktische Arzt (The General Practitioner) included treating childhood insomnia and “atonic dyspepsia,” or gastrointestinal issues. In the January, 1897 issue of Leonard’s Illustrated Medical Journal, Wollenmann provided a medicinal prescription for combatting “acute bronchitis with protracted and putrid expectoration.” He published advice to young women with irregular menstrual cycles in a 1902 issue of the Medical and Surgical Monitor. A passage from one of his articles in the General Practitioner summed up his medical philosophy: “We cannot base our therapeutic intervention on a rigid pattern;” he wrote, “at every turn nature presents us with riddles, places obstacles in our path that we must try to solve and overcome with ingenuity.” With each publication, he stressed the need for physicians to tailor their approach to the specific disease or ailment as much as possible.

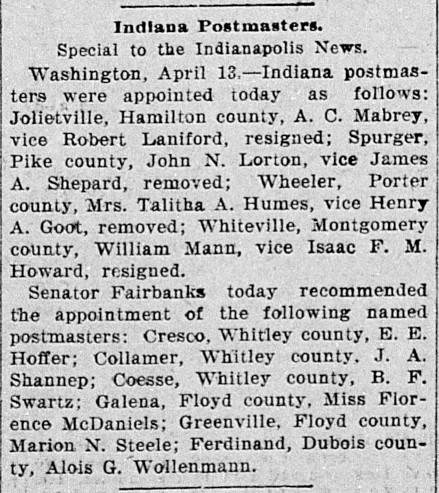

In addition to work as a pharmacist, Dr. Wollenmann ensured the safe distribution of the mail in Ferdinand as its postmaster. He received his appointment as Ferdinand postmaster on July 19, 1897, after being personally recommended for the position by US Senator Charles Fairbanks. As postmaster, he often published personalized updates for community members in the local newspaper.[iii] He also provided newspaper updates on changing railway routes and their effect on mail delivery.

While Dr. Wollenmann was deeply respected in the community for his medical work, he nevertheless experienced the brunt of controversy in 1900 (something he would experience again with his appointment of Hagan in 1904). That summer, he found himself in the middle of lawsuit, accused of “assault and battery upon Mrs. Mary Bornwasser.” According to the Huntingburgh Independent, Bornwasser visited Wollenmann’s drugstore and post office to pay some past-due postage when Dr. Wollenmann “accused her with having taken a bottle of cologne from the store the day before.” A “war of words” began between the two and Wollenmann “ejected her from the building.” The case dragged on for weeks, largely the result of a juror getting sick and the jury subsequently not agreeing on their decision; seven agreed to acquit Dr. Wollenmann and five agreed to convict him. Eventually, the case was thrown out by the presiding judge. This must have been a stressful time for Wollenmann, whose reputation was slightly tarnished by the whole affair.

From his pharmacy and post office duties to the medical services he provided to county government, Dr. Wollenmann fully adopted Ferdinand as his community, and this became more evident when he decided to build his family a new home. In the summer of 1902, the Huntingburgh Independent reported that “Dr. A. G. Wollenmann is tearing down his old dwelling house preparatory to building a handsome two-story frame in its place. It will be of the Swiss style.” In particular, it was in the Swiss chalet style and seen as “an ornament to our town and speaks well for the Doctor’s good judgement” by the local press.[iv]

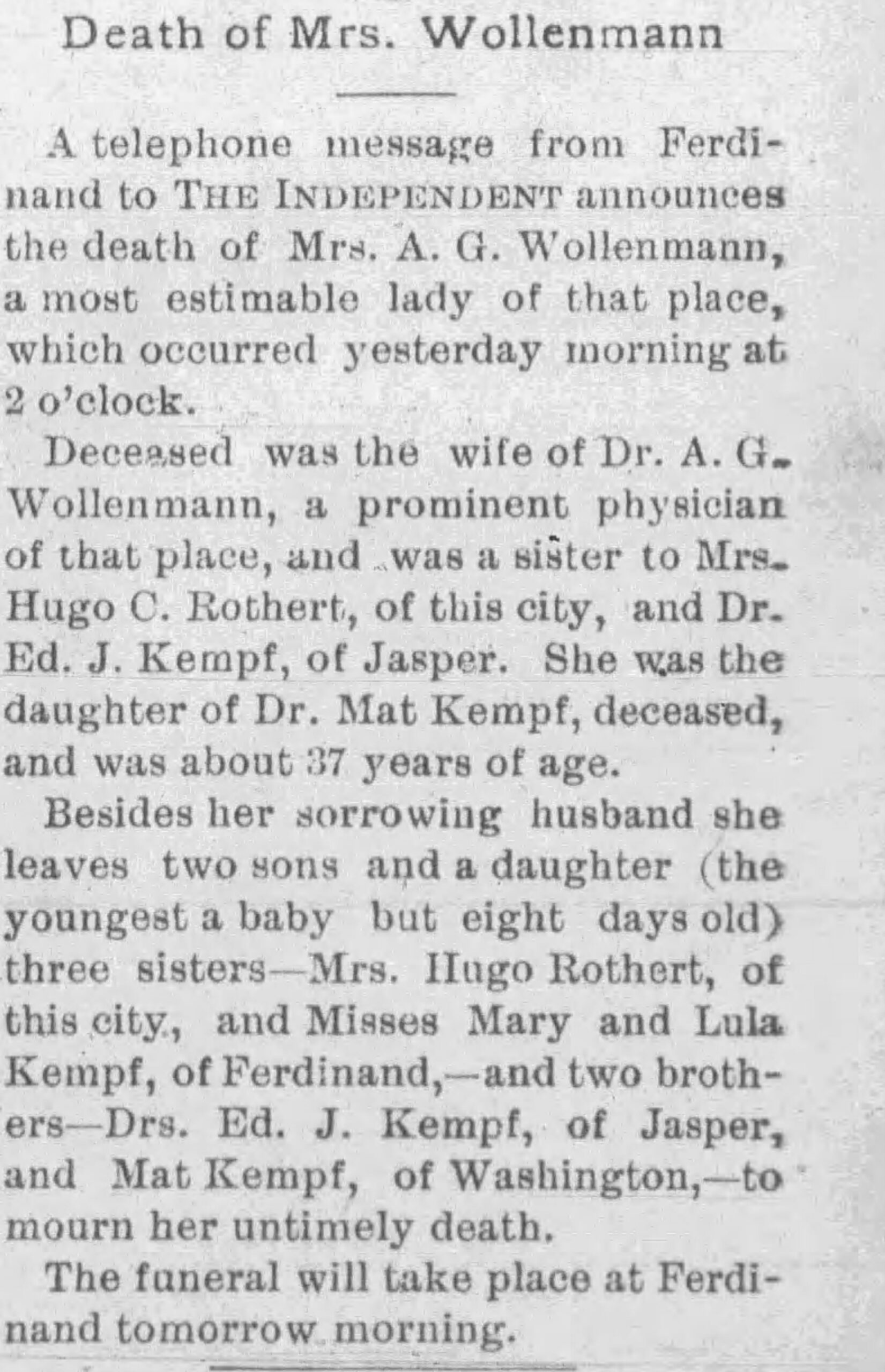

All seemed well for Alois Wollenmann as he and his family entered 1903, but tragedy would upend their happiness and change the doctor forever. In October of that year, his wife Fidelia died after giving birth to their third child, a girl named Mary Margaret, who also died shortly thereafter. He would never remarry. The grief that he experienced must have been excruciating. While this horrific chapter in his life could have broken him, Wollenmann stayed resilient and continued to serve his chosen community. It also led to his hiring of a young woman who would leave a comparable impact on Ferdinand.

Ida P. Hagan, a young resident of Pinkston settlement, a Black community west of Ferdinand, started working for Dr. Wollenmann after the death of his wife, attending to his children and home. A bright and hard-working young woman, Hagan showed professional potential that Dr. Wollenmann quickly discovered, hiring her to work in his pharmacy and post office. As Pat Backer later wrote in the Ferdinand News, “It was about this time [the death of Mrs. Wollenmann] that Dr. Wollenmann first asked Ida Hagen [sic] and a Pinkston woman to help him out” and “they would stay the week in Ferdinand helping him, and on weekends they would return to the Freedom Settlement.” With the death of Fidelia, the pharmacy and post office required a new assistant, which Wollenmann offered to Hagan in August of 1904.

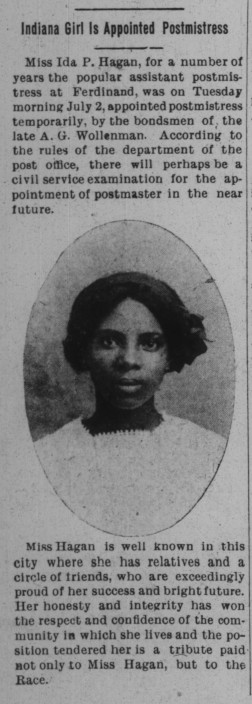

Much of the newspaper coverage of Hagan’s appointment was negative, mostly towards Dr. Wollenmann, and not Hagan herself. While the Fort Wayne Sentinel complimented Hagan as a “exceptionally good looking and intelligent young woman,” they nevertheless noted that some of the Ferdinand public “are demanding the doctor’s resignation as postmaster and declare that they will not have him as physician in their homes.” The most unnerving example comes from the Jasper Herald, which published a racist poem that mocked her appointment. An interview with Hagan appeared in the Jasper Weekly Courier, where she said “that people were glad to see her working in their homes and she cannot see why they object to her working as deputy in a post office.” Despite facing the prospect of a recall, Dr. Wollenmann kept Hagan as his deputy, the negative publicity died down over time, and he was reappointed postmaster in 1906, serving in the role until his death.

Dr. Wollenmann, believing in Hagan as a young woman with promise, took her on as a mentor. He started to train her in more than just the duties of the post office; he also educated her in medicine, encouraging her to complete a pharmacy home-study course from Winona Technical Institute, which in 1909 was “the largest school of its kind in Indiana in point of students enrolled, and it [was] the seventh largest in the United States,” according to the Scottsboro Chronicle. In her application for a state pharmacist’s license, Dr. Wollenmann submitted a letter attached to a “Certificate of Good Moral Character,” in which he wrote, “Ida P. Hagan is well prepared and qualified to pass the examination for registered pharmacist. Her character is strictly moral in every respect.” Hagan received her Indiana pharmacy license on January 13, 1909, making her one of the first known-licensed Black female pharmacists in Indiana. She subsequently resigned from her role as deputy postmaster and worked in pharmacies in Indianapolis, Gary, and somewhere in Henry County (the exact city is unknown). Wollenmann’s support of Hagan underscores his own commitment to his community and its diverse people.

The good doctor may have saved many lives, but it was ultimately his own that he couldn’t save. While his health problems likely started around 1906, when it was reported that “Dr. A. G. Wollenmann, who has been sick for several weeks, is on the road to recovery,” they likely escalated when he contracted tuberculosis in 1909, a virtual death sentence in early 20th century America (a vaccine wouldn’t be tested until 1921). As a medical professional, there’s a possibility that he contracted tuberculosis while attending to numerous patients.

As a reprieve from the effects of his illness, Dr. Wollenmann left for a three-month sabbatical to Europe in the summer of 1911, to visit his native country of Switzerland and see his sister, the Huntingburgh Argus reported. In his stead, he reappointed Ida P. Hagan as deputy postmaster to handle duties while he was gone. He returned home to Ferdinand in September, 1911.

Unfortunately, his condition deteriorated over the following months. Confined to a bed for the last three weeks of his life, “he was aware of the fact that he had not much longer to live and patiently awaited the hour that his Master would call him,” the Ferdinand News wrote. Despite all his medical knowledge, Dr. Alois Wollenmann died on June 20, 1912 at the age of 48, from complications of tuberculosis. As the Argus would write, “the dignified manner in which he consciously passed to the great beyond was a striking example.” His funeral was attended by numerous members of the Ferdinand and St. Meinrad communities, including colleagues, friends, and family. He was buried in St. Ferdinand Catholic Cemetery.

Upon Dr. Wollenmann’s death, Ida P. Hagan became Ferdinand’s acting postmaster on June 25, 1912, one of the first Black women in Indiana to hold this position. She held the position until she resigned in late August 1912, and Lula Kempf, a member of Wollenmann’s extended family was appointed temporary postmaster. Hagan’s resignation likely stemmed from her impending marriage to Alfred Roberts, her work as a pharmacist elsewhere, and her unlikely appointment to a full term. Joe Daunhaur, a civil service applicant, was appointed to a full term as postmaster on October 28, 1912.

Wollenmann left his estate, which included his home, to his sons, Werner and Max. His son, Werner, took over the family business, later served as Ferdinand postmaster, and lived in the Swiss chalet home his father built. Max, also a physician, served as an US Army surgeon and lived in Pheonix, Arizona. The original location of the Eagle Pharmacy, where Dr. Wollenmann served countless citizens of the Ferdinand community, was torn down in 1982.

“No field of human activity offers so much variety, so much encouragement to reflection, comparison and independent action, as medical practice,” Alois Wollenmann wrote in his 1895 article, “About Insomnia in Children.” ‘Variety.’ ‘Independent action.’ ‘Encouragement to reflection.’ These phrases describe who Wollenmann was, not just as a physician but as a human being. In his time in Ferdinand, he was a doctor, postmaster, and local Republican party activist—quite a variety of roles. His independent action to appoint Ida Hagan as deputy postmaster took a level of fortitude that many lacked in his era. His wide array of medical knowledge no doubt came from years of quiet and deliberate reflection. In all of these traits, Dr. Alois Wollenman embodied a man dedicated to his craft and to his community, in ways still felt today.

[i] In 1896, he was paid $13.25 by the county for his treatment of the poor; this expanded to $40 in 1899.

[ii] It is unclear if he actually recovered. A 1920 Census record lists a “Victor F. Grieve” who is around the right age, but it’s too little to be conclusive.

[iii] In July of 1907, Elizabeth Schumb failed to pick up a letter and Dr. Wollenman published a notice in the Ferdinand News encouraging it to be picked up before it was sent to the “dead letter office,” or department of undeliverable mail.

[iv] His house still stands, despite many years of uncertainty. In 2006, a request to rezone the area encompassing the Swiss chalet-style house potentially led to its demolition. Wollenmann’s granddaughters, who owned the property at the time and were initially reluctant to support the rezoning effort, finally decided to support rezoning so that the home could become a “bed and breakfast, suite of offices, or other income-generator,” the Jasper Herald reported. Despite sticking around, the home landed on the Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana’s ten most endangered list in 2007, as the rezoning could have opened it to demolition and many repairs needed to be completed. Finally, in 2014, a group of Ferdinand residents purchased the home from the Wollenmanns and transferred ownership to the Ferdinand Historical Society, who used grant funds to restore the home to its former glory. Another round of restoration got underway in 2020. The Wollenmann home finally fell into safe hands.