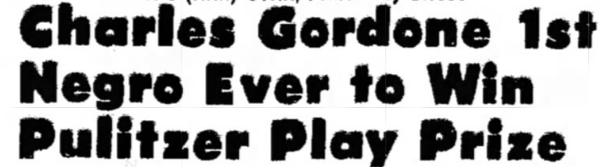

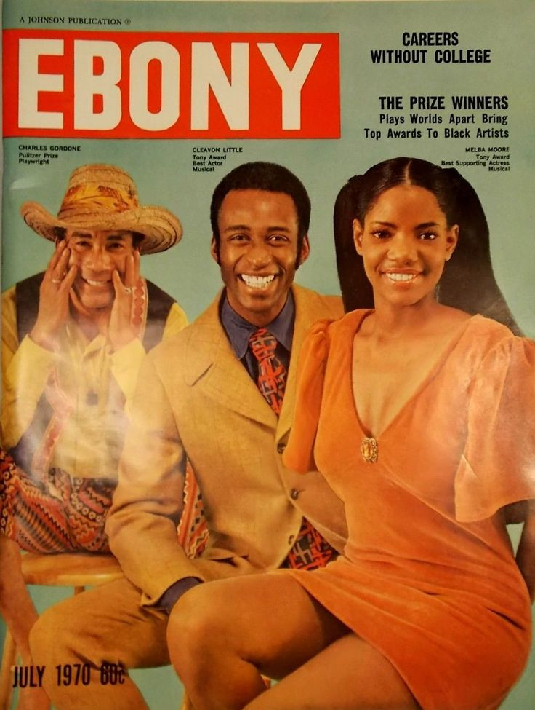

The unified efforts of the Civil Rights Movement began to fracture when in 1966 a new strategy and ideology emerged, known as the Black Power Movement. This new movement also influenced the development of the Black Arts Movement. According to historian Ann Chambers, the Black Arts Movement did not speak for the entire black community; however, the movement gave a “new sense of racial pride to many young African-American artists.” One African-American writer and actor who opposed the Black Arts Movement was Pulitzer Prize winning playwright, Charles Gordone.

Gordone was born Charles Fleming in Cleveland, Ohio, on October 12, 1925. In 1927, his mother moved with her children to Elkhart, Indiana. By 1931, she married, changing Charles Fleming’s name to Charles Gordon. He attended Elkhart High School and, although popular at school, faced racial discrimination while living in Indiana because of the divide between white and African-American children. According to Gordon, both races rejected him. White children avoided him because he was black, and the town’s African-American community shunned him because his family “lived on the other side of the tracks and . . . thought we [the Gordons] were trying to be white.”

After serving in the US Army Air Corps, he enrolled in Los Angeles City College, and graduated in 1952. Gordon stated that he majored in performing arts because “I couldn’t keep myself away from the drama department.” His experiences in college influenced his outlook on race in America. Gordon stated “I was always cast in subservient or stereotypical roles,” and he began wondering why he was not given prominent parts in Shakespeare, Ibsen, Strindberg, Pirandello plays. After graduation, Gordon moved to New York City. Once on the east-coast, Charles Gordon added an “e” to the end of his name, and became Charles Gordone when he joined Actor’s Equity Association; a labor union for theater actors and stage managers.

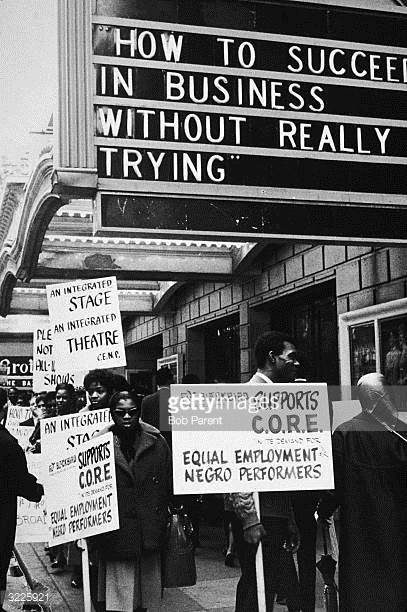

Two months after Gordone’s arrival in New York, he performed in Moss Hart’s Broadway play, The Climate of Eden, the “first of many Broadway and off-Broadway productions” for Gordone. He soon realized that black actors had a hard time earning a living in the entertainment business, and he claimed he “began to get really intense” about the lack of acting jobs for African Americans. He started conversing with many “young black actors,” and soon started picketing theaters on Broadway for better job opportunities. Similarly, fellow Hoosier actor William Walker, who portrayed Reverend Sykes in the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird, became a fierce civil rights advocate in Hollywood after being relegated to roles as a domestic servant because of his race. Walker worked with actor and future president Ronald Reagan to obtain more roles for African Americans.

Around 1963, Gordone became the chairman of the Committee for Employment of Negro Performers (CENP). Gordone claimed in 1962 and 1963 that television producers feared the withdrawal of corporate sponsorship if they “put Negroes in their shows” and that “discrimination took more forms in the entertainment field than in any other industry.”

Although the Civil Rights Movement had made extensive strides toward improving equality among the races, civil rights laws did not deter de facto segregation, or forms of segregation not “codified in law but practiced through unwritten custom.” In most of America, social norms excluded African Americans from decent schools, exclusive clubs, suburban housing divisions, and “all but the most menial jobs.” Federal laws also did not address the various factors causing urban black poverty. As racial tension mounted throughout the United States, Gordone struggled to survive in New York City. During the last half of the 1950s, out of work and broke, Gordone took a job as a waiter for Johnny Romero in the first African-American owned bar in Greenwich Village. His experiences there inspired his play No Place to Be Somebody, which he began scripting in 1960.

During the next seven years writing his play, Gordone sporadically worked in the theater industry. He was an original member of the cast for Jean Genet’s The Blacks: A Clown Show. The playwright, a white man, intended the play for an all African-American cast and a white audience. He states in his script that “One evening an actor asked me to write a play for an all-black cast. But what exactly is a black? First of all, what’s his color?”

In The Blacks: A Clown Show, African Americans wage war against the “white power structure,” and the oppressed evolve into the oppressor. Warner noted that Genet’s play put Gordone “in touch with his black anger.” In 1969, Gordone claimed that his experience as part of the cast changed his life because the play dealt with problems about race, enabled him to confront the “hatred and fear I [Gordone] had inside me about being black,” and introduced a talented group of African-American actors to the entertainment media including James Earl Jones and Maya Angelou.

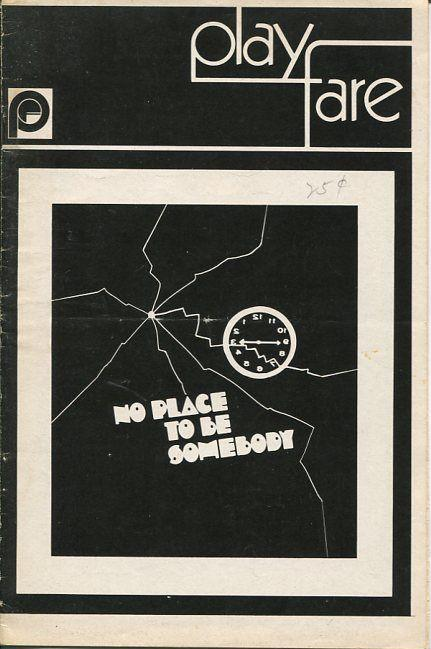

Gordone finished his own play, No Place to Be Somebody, in 1967. The plot of the play revolves around an African-American bar owner named Johnny Williams. Other characters include a mixed-race actor, a black homosexual dancer, a Jewish strumpet, a black prostitute, an Irish hipster, an aging black hustler, a member of the Italian mafia, an influential white judge, and the judge’s idealistic daughter. Johnny Williams, is a tavern-owner, pimp and wannabe racketeer. His foil, Gabriel, also an African-American, is an intellectual struggling to be accepted as a legitimate actor.

According to a New York Times reviewer, the characters are forced to try and survive in a society controlled by white standards. Johnny Williams possesses a desire to become “somebody” in Italian-run organized crime; Gabriel fails in his attempts to be cast in African American roles because he is light-skinned. The characters’ actions in No Place to Be Somebody are influenced by racial and cultural pressures directed towards characters of opposing races. According to Gordone, “It [the play] is the story of power, about somebody who is stifled who was born in a subculture and feels the only out is through the subculture.” By the end of the play, most of the characters fail in obtaining their goals because they have all set their “ambitions in excess of their immediate limitations.”

Gordone originally offered the play to the Negro Ensemble Company (NEC); an acting group rooted in the Black Arts Movement. He claimed the co-founder, Robert Hooks, turned it down because the NEC did not allow white actors in their theater troupe. Gordone and Warner produced a “showcase version” of the play at the Sheridan Square Playhouse in 1967, but “the response wasn’t too good.” Gordone and Warner lost all their money in the venture. But in 1969, the play was accepted for the “Other Stage Workshop,” in Joseph Papp’s Public Theater, at the New York Shakespeare Festival.

No Place to Be Somebody opened on May 4, 1969 to mixed reviews. New York Times reviewer, Walter Kerr, compared Gordone’s work to Edward Albee’s masterpiece, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Other reviews called the play “engrossing,” “powerful,” and hailed it as one of the “unique” plays of 1969. On the contrary, influential African-American critic, Clayton Riley, blasted the play’s poor production and directorial choices. Riley also questioned Gordone’s “incomprehensible” dialogue, depiction of “self-hatred,” “contempt for Black people,” and his “desire to say too much.” Yet, Riley did state that Gordone possessed “splendid talents.” According to Gordone, Riley’s review “hurt Riley more than me [Gordone] … brother Clayton is uptight. He can’t face it that The [white] Man is helping one of his brothers.”

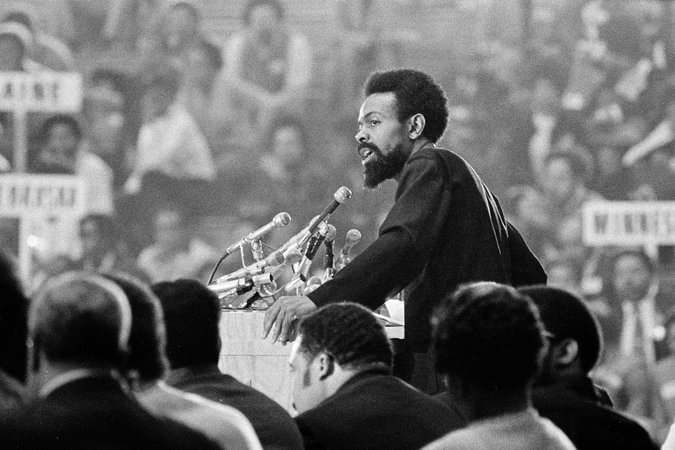

According to a 1982 interview, Gordone’s views on race “alienated many blacks.” Gordone argued, in a 1970 New York Times editorial piece, that writers like LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) should write about more than “how badly the black man is treated and how angry he is.” Gordone believed such theater intensified the split amongst the races, and he questioned “Is black really ‘beautiful’? Or is that beauty always hidden underneath the anger and resentment?” According to Gordone, Jones’ writing was “egotistical, smug, angry (never violent), frightened, and damning of every white man in the world,” and Gordone took offense that Jones was “attempting to speak for all people of color in this country.”

According to Mance Williams, Gordone opposed the Black Arts Movement’s notion that the “Black Experience is a singular and unique phenomenon.” Gordone believed that African-American culture was one part of the larger American Culture, reasoning that without the “white experience,” there cannot be a “black experience.” Williams states that Gordone believed the races were interrelated, and helped create the unique qualities that defined the “white” and “black” races. In a 1992 interview, Gordone said “We need to redefine multiculturalism. There’s only one culture—the American culture, and we have many ethnic groups who contribute.”

One possible explanation for Gordone’s belief in multiculturalism is the fact that he claimed his ancestral makeup consisted of “part Indian, part French, part Irish, and part nigger,” and he jokingly called himself “a North American mestizo.” Williams claims the playwright deemed the “color problem” could only be resolved through cooperation between the races, and that is why Gordone shied away from any radical political movements that could further divide the races. However, according to Gordone, his exclusion from the Black Arts Movement left him “Dazed, hurt, confused, and filled with self-pity.”

Gordone claimed his professional success put tremendous pressure on him. Winning the Pulitzer Prize made Gordone unhappy because he was acclaimed as a writer, rather than a director. According to Gordone, “every time you sit down at a typewriter, you’re writing a Pulitzer Prize. You’re always competing with yourself and you have to write something that’s as good or better.” In 1969, he began drinking heavily, hoping “get the muse out of the bottle” after the “long struggle.” During Gordone’s battle with alcoholism, he still worked in the theater industry. He got involved with a group called Cell Block Theater, which used theater as therapy as part of an inmate rehabilitation program.

In 1981, Gordone met Susan Kouyomjian and in 1982 they founded The American Stage, an organization devoted to casting minorities into non-traditional roles, in Berkeley, California. The American Stage productions included A Streetcar Named Desire with a Creole actor playing Stanley; Of Mice and Men with two Mexican-American actors playing George and Lenny; and The Night of the Iguana with an African American actor in the lead role of Shannon. According to Gordone, he and Kouyomjian never overtly wanted to provide more opportunities for “black, Hispanic and Asian actors,” but Gordone said “it is now very much my thing.” Their goal was to logically cast actors “so that you don’t insult the work’s integrity.” Gordone believed “innovative casting enhances the plays,” and makes them so exciting that “it’s almost like you’re seeing them for the first time.”

In a 1988 interview, Gordone continued commenting about the portrayal of race in contemporary literature and theater. Susan Harris Smith asked if theater critics viewed Gordone as “black first and a writer second?” He replied “Yes” and commented the practice was “racist.” He claimed he was a playwright trying to “write about all people . . . and to say I [Gordone] have a black point of view is putting me in a corner.” He believed African-American critics finally reached a “significant realization” about the theme of No Place to Be Somebody, that “if blacks walk willingly into the mainstream without scrutiny their identity will die or they will go mad.”

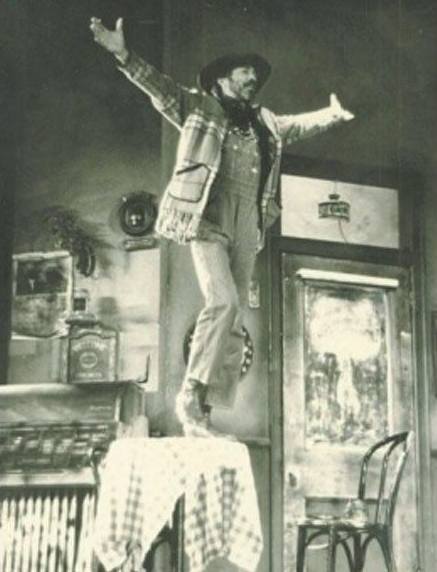

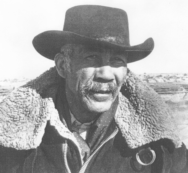

In 1987, Texas A&M University hired Gordone to teach in the English and Speech Communications Department. There, Gordone began embracing the American-western lifestyle or “cowboy culture.” The playwright stated, “The West had always represented a welcoming place for those in search of a new life,” and he found a “spirit of newfound personal freedom” within the American West. Gordone remained in Texas until his death on November 16, 1995. Friends and family scattered his ashes in a “traditional cowboy ceremony, with a riderless horse” near Spring Creek Ranch, Texas.

Learn more about Gordone via the Indiana Historical Bureau’s historical marker.