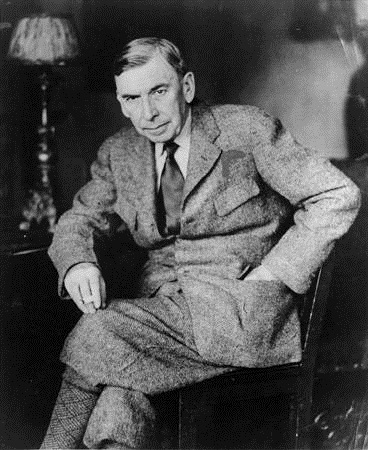

On December 17, 1942, the Indianapolis Times noted that Pulitzer-Prize winning author Booth Tarkington was not only a master novelist, but a “student of human nature.” This is evident in the pieces he penned for local newspapers regarding his belief that national isolationism contributed to global war. Prior to America’s involvement in World War II, during the conflict, and following the United States use of the atomic bomb to end it, Tarkington continually plead for national engagement as a way to prevent future bloodshed.

Tarkington knew a thing or two about political activism. Born in Indianapolis in 1869, he earned widespread literary acclaim with his first novel The Gentleman from Indiana (1899). The popularity of this book and his successive Monsieur Beaucaire proved enough to win election to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1902. The Columbus Republic noted that although Tarkington “is unknown to the party workers, the fame of his stories have been sufficient to land him a nomination.” He easily won the elected office without campaigning, but served only one session after becoming completely disillusioned with politics. However, he utilized his legislative experience as material for his 1905 book, In The Arena, which was set in a fictional midwestern legislature.

Although he stepped away from the Statehouse, Tarkington’s political activism never waned, particularly regarding America’s involvement in war. Prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he lent his voice to the American minority that supported engagement in the war. He traced the growing European conflict back to the United States’ decision not to join the League of Nations, an international organization proposed by President Woodrow Wilson after World World I. The League sought to prevent war by providing “a forum for resolving international disputes.” According to Tarkington, America’s retreat from the international sphere created a “pacifist nation.” He wrote, “There grew up a belief that it was a kind of a silly war, and that England led us into it. Then war was made disreputable.” This detachment, he said, led Americans to overlook legitimate national security threats.

The U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian noted that a “combination of the Great Depression and the memory of tragic losses in World War I contributed to pushing American public opinion and policy toward isolationism.” Sensitive to this, President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised to keep America out of the war abroad and convinced Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Bill in March 1941. The bill enabled the United States to dispatch badly-needed arms and war supplies in an attempt to the help Britain defeat Hitler’s forces and to stall its own military engagement.

Appraising the Lend-Lease Bill, Tarkington posited in April 1941 via the Indianapolis Star that simply supplying arms would likely prove too little too late, noting “Having done our best to keep out of war, we now either take another chance of getting into it or await our own turn with the Nazis, which might not mean a long waiting.” He added, “Every intelligent American knows now . . . that his country and his family and he, himself, are imperiled by Hitler’s will to ruin them for the aggrandizement of Nazi power.”

On December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor forced the United States into military involvement. Congress declared war on Japan the following day. Tarkington noted in an interview published in the Indianapolis Star in January 1942 that “the day of isolationism is past, whether you like it or not.” He conflated America’s absorption into the conflict abroad with his move from his house on Pennsylvania Street to Meridian Street in Indianapolis, stating that his old “neighborhood is almost downtown. It was considered some distance out in earlier years . . . The same thing is happening in the world today. There are more people-the world is more concentrated.”

After learning of the casualties of WWII, Tarkington suggested in December 1942, that engagement proved more necessary than ever because humans are “self-seeking” and “still pretty close to prehistoric savagery.” Unchecked, they were “‘slashing at each other’s jugular veins'” and countries had “gone back to wholesale murder.” Tarkington put his money where his mouth was, in terms of engagement, as the motorboat at his Maine home was “commandeered for an auxiliary flotilla to discourage submarines along the coast. Mr. Tarkington went out almost every day to do his bit at ‘soldiering.'”

The Hoosier author looked towards the conclusion of the war, having no doubt that the Allies would win. He again returned to the idea of the League of Nations, noting “We’re going to justify Woodrow Wilson . . . The country is ready to do that now.” Americans had been hesitant to join such a council for fear of losing autonomy, but Tarkington felt that American interests could be assured while collaborating with nations to stamp out global aggression.

A member of the Indiana Committee for Victory, Tarkington posed a question to Indiana Republican candidates for Congress on April 30, 1944. He asked, via the Indianapolis Star, “How shall the United States obtain a peace that will be permanent?” He proposed his own plan, which involved the United States passing a law to outlaw war and inviting other nations to form an organization “in which every concurring nation should have the same number of representatives.”

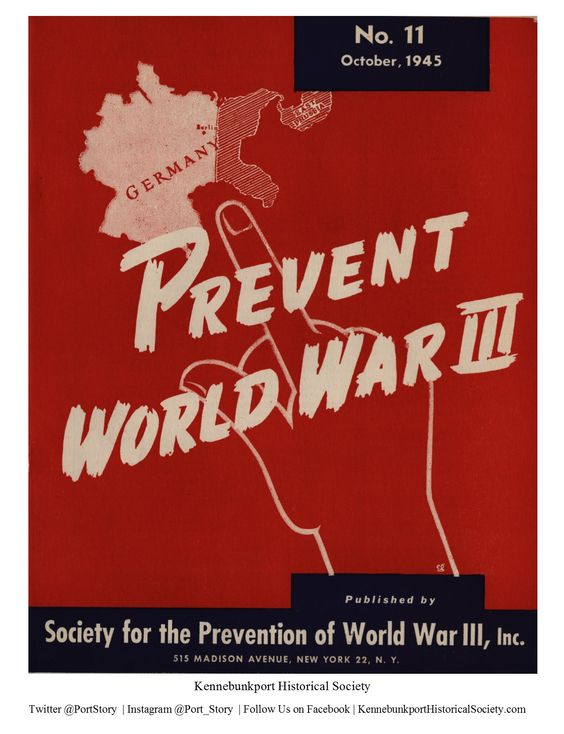

According to his proposal, all nations would disarm and “any country making war or preparing to make war, no matter in what cause, would bring down upon itself the overwhelming force of all the rest of the world.” Tarkington’s question became increasingly important after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. In a piece for the Indianapolis News, entitled “Fools Will Burn,” Tarkington wrote “that fire flash lets us know that we are crossing a strange threshold, stumbling dazed into a new period promptly to be more dangerous to man than the Ice age or the too near approach of a comet.”

In this article, Tarkington challenged the long-held assumption that advancements in weaponry could prevent war by generating fear of increasingly-horrific repercussions. He lamented, “there were more wars; always there were governments that took the people into the new annihilation.” Tarkington considered Congress’s proposal to safeguard the process of developing an atomic bomb laughable. He lampooned this attempt at nuclear exclusivity as “comedy at its lamentable zenith and the bill should be passed by a convention of ostriches. Congress may as well pass a measure keeping electricity a secret and outlawing the use of gasoline engines in Persia.”

In Tarkington’s view, the only thing that could preclude military conflict was engaging with other nations and persuading them to outlaw war. He likened the global interdependence of the early atomic age to a “a family living in a house with walls irretrievably built of dynamite.” Family members who disliked each other had to be counted on to “walk softly” and “not to be irritating to one another.” The household, he suggested, would need an “impartial watchman” to ensure that “nobody jars the walls or has any possible chance to jar them. Disputes in the family would have to be settled without pummelings. Any physical violence at all might set off the dynamite.” This watchman, Tarkington concluded, should be the security council of the United Nations, which “must have complete control of the A-bomb.” On October 24, 1945, this council officially came into existence, when the United Nations Charter was ratified, creating an “international organization designed to end war and promote peace, justice and better living for all mankind.”

Tarkington died on May 19, 1946 in Indianapolis, shortly after the formation of the council. Tarkington’s concerns about nuclear proliferation are more relevant than ever and call to mind his 1945 assertion that “Only suicidal madmen would think A-bomb races with anybody an attractive idea. Mankind has a practical choice between suicide and peace.”

Learn how vigilant Hoosiers sought to deter nuclear catastrophe from their own backyard with the early atomic age Ground Observer Corps program.