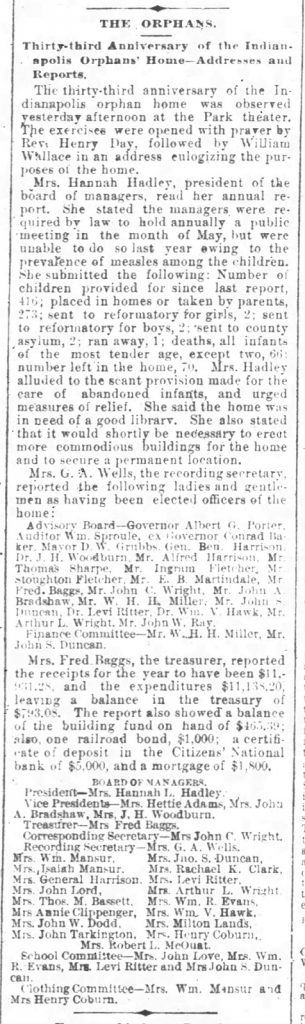

Eddie Anderson had been at the asylum for a mere fifteen days, and it already looked like he would be leaving. On September 15, 1882, a man known as Dr. Harvey brought the ten-year-old boy from Hendricks County to the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum, the city’s first and oldest orphanage. Now a Mrs. Skillman, who had traveled over seventy miles from her home in Peru, Indiana, took Eddie from the orphanage. On September 30, 1882, the president of the Board of Directors, Hannah Hadley, and Mrs. Skillman signed an indenture for Eddie Anderson, essentially agreeing that Eddie would work for Mrs. Skillman in exchange for room and board. Mrs. Skillman agreed to “carefully keep and rear” the ten-year-old boy until he reached the age of twenty-one and give him $100 at that age. After signing the contract, Mrs. Skillman left as Eddie’s new guardian.

More than twenty years later, in December 1903, Eddie wrote to the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum from Sharpe, Kansas. He received no answer. After waiting several months, he wrote again.

Sharpe Kansas

Mar. 23 1904

Superintendent of the Orphants [sic] Home

Kind Sir-

I wrote to you in Dec. 1903 and as yet I have not heard from you and fearing my letter or yours was misplaced I now write again, as I am interested to find out about my record and in what condition I was taken out of the Orphants [sic] home by mrs [sic] Skillman some 20 years ago.

Eddie begins his letter in a somewhat neutral tone but quickly becomes distressed as he recounts his experience with Mrs. Skillman.

My name… I know was Edd Anderson but they changed it to Elmer Anderson and did me other meaness [sic]. I am totally ignorant of myself. they used to pretend as though I was adopted and was to get part of their estate… [when] I was of age then they turned me off without clothes hardly good enough to wear and not a cent to go on; now please do what you can for me if you have any knowledge as where my folks are please let me know and all that is of interest to me as I have been informed that my name, age, and record you will have in your ledger. some of mrs Skillmans relatives say she had papers that I should of got concerning me and my relatives but they distroyed [sic] them so please now help me all you can…

Eddie’s letter does not reveal the story of a child who was “carefully kept and reared” and given $100 dollars when he turned twenty-one. Rather, it reveals the story of an individual searching for his past and his identity. Unfortunately, Eddie’s letter to the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum (IOA) is an exception—few children left behind written records of their indenture experiences. Nevertheless, the indenture documents contain vital information—such as demographic information and expectations for both the adults and children—that allows the historian to piece together a lost story (like Eddie’s) and refocus the narrative on the ones who were affected most by 19th-century orphanages—the children.

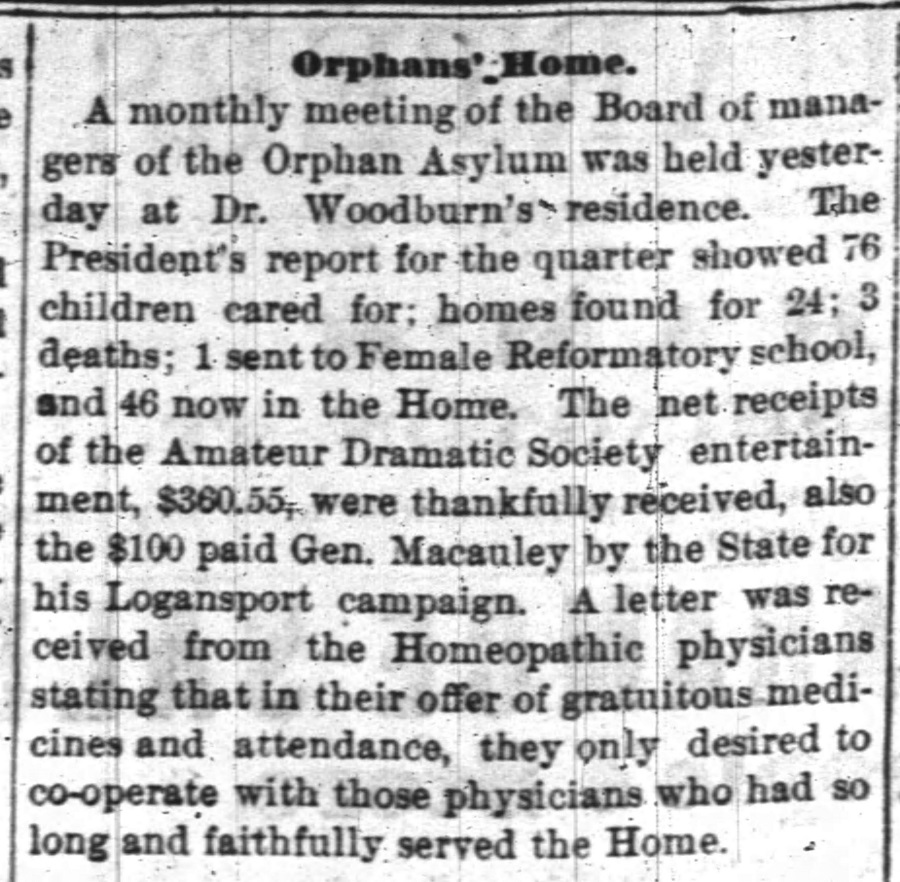

During the 19th century, indenturing children was a relatively common method to care for dependent children. At the IOA, an indenture was signed between the institution and an adult—the child, arguably the one affected most by the indenture, was not involved in that process. The Indiana Historical Society contains 152 indenture contracts (including Eddie’s) from the years 1875 to 1885 in their collections. An examination of these records reveals insight into 19th-century childcare practices in Indiana.

IOA indenture contracts began by identifying “the parties”—the institution and the adult guardian. An IOA indenture from the 1870s states “This indenture . . . witnesseth that the said parties of the first part [the IOA], in consideration of the covenants and agreements of the said party of the second part [the individual receiving the child] . . . do put and bind . . . an orphan child . . . unto the said party of the second part.” At the very outset of the contract, it is stipulated that the child is “put and bound” to the individual and that the individual receives the child’s “service and custody during said period, which by the laws of the State a master has over an indentured apprentice.” The indenture contracts used by the IOA clearly show that children in the care of the institution were placed in homes in exchange for their labor.

While the indenture contracts clearly state that a child’s service is given to an adult guardian, they also identify the responsibilities of the new guardian. At least one-third of the contract stipulated requirements for the adult. The asylum required the new guardian to “covenant and agree” to “carefully keep and rear” the child; “provide for [him/her] in sickness and health”; and “supply [him/her] with suitable food and clothing.” In addition to these vital necessities, the indentured child’s new guardian was also required to “teach [him/her] to read and write the English language, and to know and practice the general rules of arithmetic, including ‘to the double rule of three inclusive.’” Thus, in addition to providing for the child’s physical needs, adult guardians had to educate an indentured child as well. In an ideal setting, the child would also learn “some useful trade or occupation,” but only if the guardian “deemed [it] best.” The IOA clearly stated its expectations of adult guardians.

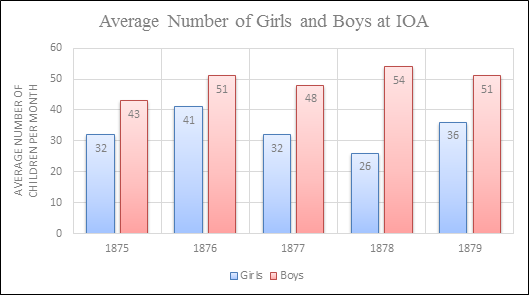

In addition to providing information about the expectations regarding 19th-century indentures, the contracts reveal insight notions of gender during the era. Of the 152 IOA indentures, 91 of the children (sixty percent) were female, and 61 of the children (forty percent) were male. This number is not representative of the ratio of girls to boys at the IOA, because, during the same time frame, there were significantly more boys than girls at the asylum. Throughout the 1870s, there were on average sixteen more boys than girls per month at the IOA. In 1878, the average number of girls per month at the asylum was less than half of the number of boys.

Intriguingly, the number of boys and girls indentured does not reflect the number of boys and girls at the asylum—if anything, it is the opposite.

In 1878 for example, fifteen children were indentured with the number of boys indentured drastically lower than the number of girls. In 1878—a year when there was an average of twenty-eight more boys than girls per month (see figure 1)—four of the fifteen children indentured (twenty-seven percent) were boys. The remaining eleven children (seventy-three percent) were girls. Despite the much higher percentage of boys at the asylum, a higher number of girls were indentured.

The higher number of girls indentured could be because adult guardians had to give boys more money when they completed their indentures. With the IOA indentures, boys almost always received $100 to $150 upon completion of their indentures, while girls received $5, $10, $25, $50, or simply a bed, bedding, and two suits of clothing. Lizzie Young Conversa was one year old when she was indentured on April 12, 1876. The IOA agreed to indenture her for the next seventeen years, with only the promise of five dollars and “a good bed and bedding and two suits of suitable clothing” at the end of her indenture. According to the contracts, boys were indentured until the age of twenty-one while girls were indentured until the age of eighteen (or until they got married). This could be another reason why adult guardians preferred girls over boys—they did not have to commit to caring for a girl as long as they had to commit to caring for a boy.

The preference for indentured girls over boys indicates that notions of gender and masculinity limited the tasks a boy could perform. According to Birk, “While boys helped as physical laborers, farmers and their wives wanted girls who could assist with housework. Placed-out girls often performed jobs identical to those of the women of the house.” These jobs included “making breakfast before moving on to tasks such as laundry, ironing, mending, cooking, and farm chores such as milking, caring for chickens, gardening, or aiding in field work.” So, while boys only helped with farm work, girls helped with housework and farm work. Because of notions of gender responsibilities and masculinity, it is extremely unlikely that a boy would have helped with laundry, cooking, or cleaning. However, a girl could help with gardening, field work, milking, and caring for animals in addition to laundry, cooking, and cleaning. It comes as no surprise then that adult guardians preferred indentured girls over indentured boys, since they did not have to provide for girls as long; they did not have to pay girls as much (if anything); and they could use girls to work in both the house and on the farm.

Overall, the IOA indenture records tell only a small portion of a child’s story. Of the 152 children, how many fulfilled their indentures in a home-like environment? How many were treated as free labor and shown no love? How many ended up like Eddie, searching for their family, their past, and their very identity? Although these indenture contracts do not contain the answers, they do provide a means for putting children back into the story of nineteenth-century orphanage policies.