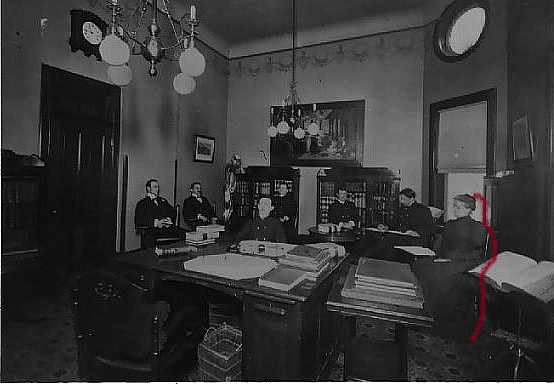

Dr. Sarah Stockton earned a reputation as a gritty, compassionate physician at the Indiana Hospital for the Insane (later renamed Central State Hospital). According to a Moment of Indiana History, her appointment as assistant physician in the Women’s Department in 1883 was regarded as “significant enough to the cause of women’s rights as to merit mention by no less prominent an advocate than Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in History of Woman Suffrage.” Patients, like Anna Agnew, also praised her appointment. Agnew recalled in her 1886 reminiscences, “I felt the first time she came into my darkened room, where I lay in such agony as only miserable women suffer, and seating herself at my bedside, looking pityingly at me, the expression in her lovely blue eyes in itself a mute promise of assistance, before a word was spoken, that an angel had been with me.” Dr. Stockton was remarkable not only for her prolific medical career, but her tireless work for women’s suffrage.

According to the Lafayette Journal and Courier, Stockton was born on a local farm in 1842, the daughter of “pioneer settlers of Tippecanoe county.” She and her sister operated the Stockton boarding house in Lafayette, before she studied at the Woman’s Medical College in Philadelphia. Stockton graduated in 1882, penning a doctoral thesis about the history of insanity and the treatment of mental illness. An article in the Indianapolis News noted that she also graduated from a “Female medical college of Chicago” and practiced at a Woman’s hospital in Boston. In 1883, Indiana Hospital for the Insane Superintendent Dr. William Fletcher appointed Dr. Stockton to the woman’s department. He stated in 1884:

It may not be that a larger number of women would recover under special treatment, but it would be a comfort to every parent, brother, and sister, to know that their afflicted loved ones who are insane from the fact of being a woman, were to fall into the hands of a cultured and refined female physician when shut behind the hospital bars.

The progressive superintendent-who abolished the use of restraints and advocated moral treatment of patients-lauded Dr. Stockton’s accomplishments and those of female doctors in general. He noted at a medical conference that her appointment to the “woman’s department has proven a great benefit to a large class of patients hitherto utterly uncared for, so far as their special maladies were concerned.” He added “I do not understand how a hospital for insane women can reach its best results without the kindly aid of educated, skillful medical women.”

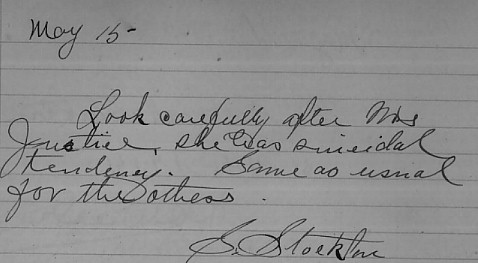

In the era during which Dr. Stockton practiced, many in the medical establishment believed that reproductive organs and menstrual function correlated with mental disorders. According to Nicole R. Kobrowski’s Fractured Intentions: A History of Central State Hospital for the Insane, “It was believed that because of the nervous energy and cerebral movement, the body used the menstrual blood as a power source for the body,” therefore irregular periods and menopause could induce insanity. In her 1885 “Report of Special Work in the Department for Women,” Dr. Stockton generally ascribed to this theory, but noted that she did not “believe that in every instance it takes part in causing insanity.” She wrote:

Agitation of the mind from external influences, or increased cerebral excitement that calls for a greater amount of blood and nervous energy, will for a time arrest the menstrual flow. In those cases removal of the exciting cause, with remedies that will aid in restoring the nervous and mental equilibrium, will usually result in a return of menstruation, and prove to be the first evidence of recovery.

Generally this treatment consisted of applying tonics to the “pelvic organs” and occasionally required surgery. Dr. Stockton’s “bedside manner,” and the fact that she was a female physician serving in a woman’s department, proved as important to patient health as medicinal treatment.

In her Personal Reminiscences of Insanity; Or, Personal Reminiscences of Insanity, Anna Agnew expressed how vital Dr. Stockton’s presence was to her recovery, noting “If I could only express the hopefulness her words inspired, not that I cared then to live, for I did not, but I was so thankful to be relieved from my terrible physical sufferings, and she was so handsomely dressed, too!” Agnew was deeply moved by Dr. Stockton’s compassionate treatment, writing:

And I still retain my admiration for my friend, and have added to my admiration of her personal appearance and intellectual endowments-love-for her never failing kindness and sympathy toward me in my sorrowful life. Thus this advantage one possesses in having a woman for your physician.

In fact, Agnew so valued Dr. Stockton she admitted that although she was not a women’s rights activist, “I do with all my soul sanction, her education as a physician! And for the sake, and in behalf of suffering woman-insane women in particular-since they can not tell their misery, I make an appeal to the board of trustees of every female hospital for the insane in the land, for the appointment of a woman upon their medical staff.” Dr. Mary Spink, an Indianapolis doctor who practiced during the same period, noted similarly that female patients preferred women doctors because “‘the man’s policy is to always laugh and make fun of hysterical and nervous women. . . . it makes the poor women mad, just the same, and they naturally seek more sympathizing ears.'”

While at the Indiana Hospital for the Insane, Dr. Stockton was pressured by administrators to overlook dismal hospital conditions, resulting partly from lack of funding and staffing. However, she bravely testified in February 1887 that the butter was filled with worms, which was “not an uncommon thing.” In March 1889, the Indianapolis Journal reported on an investigation into the hospital’s conditions. Dr. Stockton again testified against the institution, despite dreading “the ruling powers at the hospital.” CC Roth, former assistant storekeeper, alleged that the trustees “‘had it in for anyone’ who disclosed the entire truth about the hospital, and that of the witnesses at the investigation two years ago those who told the truth about Sullivan’s maggoty butter and the conduct of the trustees had one after another been discharged.”

Indeed, Dr. Stockton was fired as a result of her testimony. However, she “did not heed its insolent imperiousness, but took time to withdraw from the place she has served so long and so faithfully with the deliberation that any person under like circumstances would employ.” One hospital trustee lamented her dismissal and the politics surrounding it, noting that Dr. Galbraith “was the most inefficient man who ever held the position of superintendent at the hospital, and that Dr. Stockton was the only really capable physician out there.”

Dr. Stockton continued to practice medicine after leaving the hospital, working at former superintendent Dr. Fletcher’s private sanatorium in Indianapolis (later known as Neuronhurst).

In 1891 she served as physician at the Indiana State Reformatory for Girls and Prison for Women. Around 1900, Dr. Stockton returned to her former hospital, renamed Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane. Ten years later, the Indianapolis Star hailed her as a pioneer in her field, noting “Not longer than thirty years ago there was only one woman physician in Indianapolis-Dr. Sarah Stockton. Now there are fifty.” Similarly, the Arkansas Democrat described her in 1916 as “one of the leading women physicians in the United States.”

Early-20th century newspapers reported on the noted physician’s suffrage work. Illustrating why the fight for women’s equality was necessary, Dr. Spink stated that women doctors rarely married and that “the average man won’t enter the connubial harness with a woman who can’t attended to household duties.” Dr. Maria Gates was the only Indianapolis doctor at the time who married and it is “a significant fact that she dropped the ‘Dr.’ the moment the knot was clinched.”

The Indianapolis News stated in December 1915 that Dr. Stockton was slated to present a paper titled “The Woman Physician” at the Indianapolis branch of the Women’s Franchise League as part of a panel about women in “professional and business life.” In January 1917, nineteen stenographers signed a petition to protest the anti-suffrage movement in Indiana, citing suffrage as “a weapon that business women needed in dealing with the business world.” Nineteen graduates of Vassar College signed a similar petition. Dr. Stockton joined nineteen women doctors who also signed a pro-suffrage petition “‘just because it is right.'” In 1920, she gave a talk at a reminiscence meeting of the Indianapolis League of Women voters, along with other notable Hoosier women like Mrs. Meredith Nicholson and Miss Charity Dye.

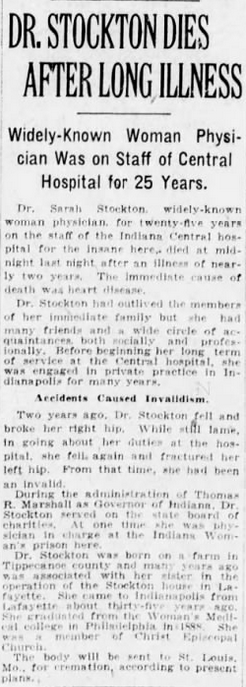

After dedicating twenty-five years of service to Central State Hospital and fighting for women’s right to vote, Dr. Stockton passed away at midnight of March 14, 1924. The Indianapolis Star reported that the “widely-known woman physician” had a “wide circle of acquaintances, both socially and professionally.” Most notably, she provided solace for countless female patients in an otherwise desolate hospital environment.