The history of the traditionally Irish-Catholic University of Notre Dame located in South Bend, Indiana, has paralleled the larger story of Catholic immigrants making their way in the United States. Starting as a persecuted minority, Irish Catholics integrated into the fabric of the American tapestry over the twentieth century. [1] The challenges and threats posed to Notre Dame in the 1920s, mirrored those periling Indiana, the United States, and in many ways, democracy. As Americans reacted to shifts in U.S. demographics brought by immigration and urbanization, those threats to equality and justice included rising nationalism, animosity toward Jews and Catholics, discrimination against immigrants and refugees, and even violence against those not considered “100% American.” No group represented these prejudices as completely as the Ku Klux Klan. While the Klan had gained political power and legitimacy in Indiana by the early 1920s, it had yet to find a foothold in South Bend or larger St. Joseph County. The Klan was determined to change that. [2]

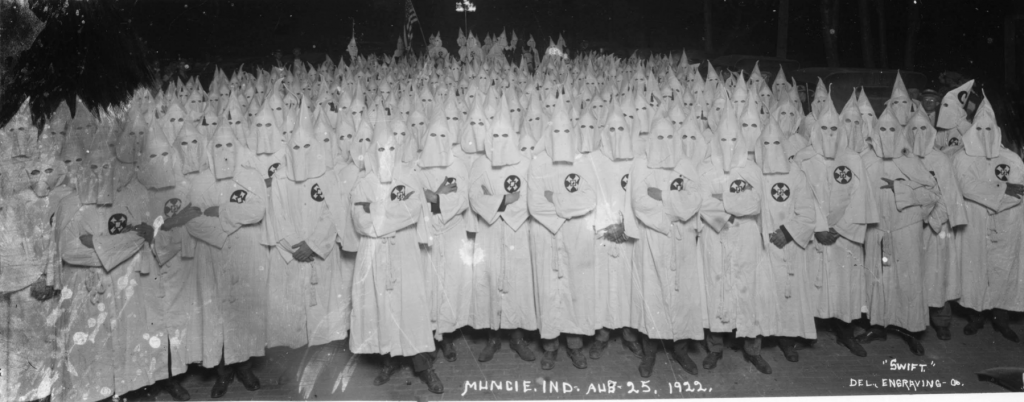

University of Notre Dame leaders and officials understood that the only way to combat the xenophobia and anti-Catholicism of the Ku Klux Klan, while maintaining the school’s integrity, was to not play the Klan’s game. So the school chose another – football. During the 1920s, renowned coach Knute Rockne led Notre Dame’s football team to greatness. But these athletes fought for more than trophies. They played for the respect of a country poisoned by the bigoted, anti-Catholic rhetoric of the Klan. They played to give pride to thousands of Catholics enduring mistreatment and discrimination as the Klan rose to political power.

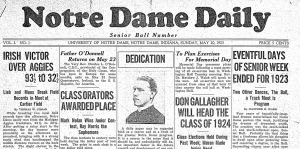

By 1923, the young scholars writing for the Notre Dame Daily, the student newspaper, expressed concern over the rise of the Klan. Several students had also given speeches on “the Klan” and “Americanism.” The Klan’s use of patriotic imagery particularly bothered the young scholars. In one Notre Dame Daily op-ed, for example, the writer condemned the Klan’s appropriation of the American flag in its propaganda while simultaneously “placing limitations upon the equality, the liberty, and the opportunity for which it has always stood.” [3]

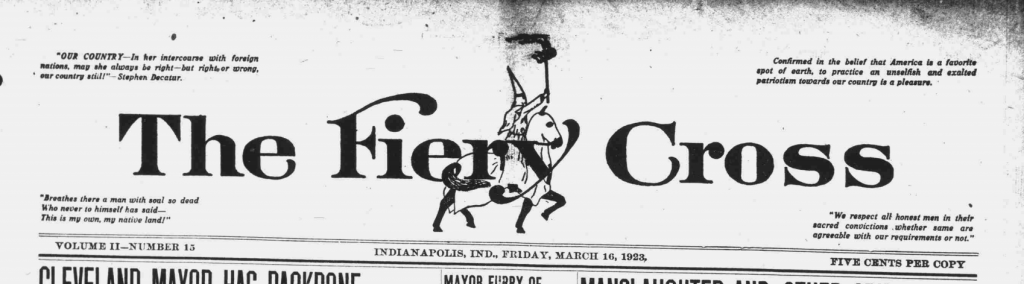

This was not only a philosophical stand. For the students of predominately Catholic and of Irish immigrant origin, the Ku Klux Klan posed a real threat to their futures. The Indiana Klan was openly encouraging discrimination against immigrants, especially Catholics. The hate-filled rhetoric they spewed through their newspaper, the Fiery Cross, as well as speeches and parades, created an atmosphere of fear and danger for Hoosiers of the Catholic faith or immigrant origin. The Klan encouraged their membership not to do business with immigrants, worked to close Catholic schools, and most destructively, elected officials sympathetic to their racist position and lobbied them to impose immigration quotas. [Learn more about the Klan’s influence on immigration policy here.] While the 1920s Klan was a hate group, it was not an extremist group. That is, its xenophobia, racism, anti-Catholicism, and antisemitism were the prevailing views of many white, Protestant, American-born Midwesterners. In other words, the students of Notre Dame had to worry about facing such prejudice whenever they left campus – even for a football game. [4]

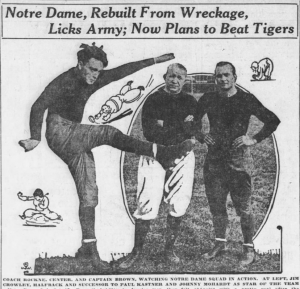

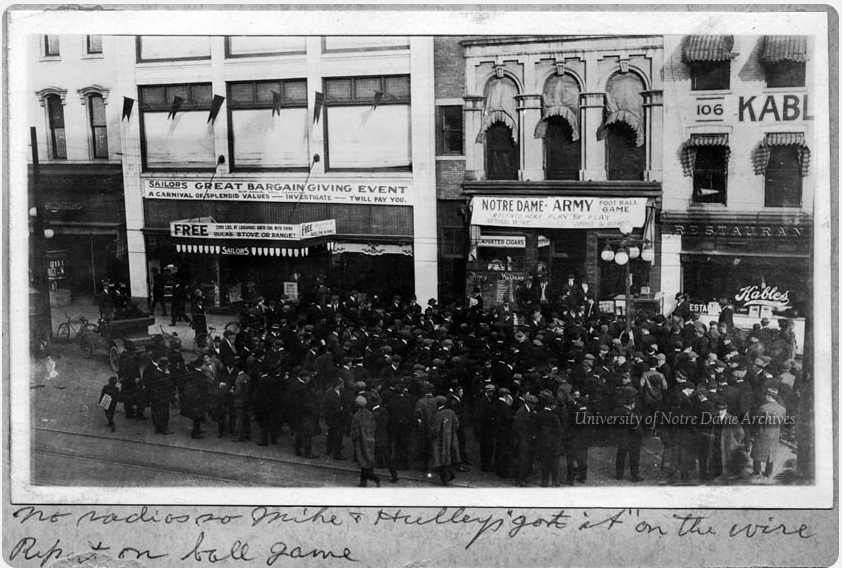

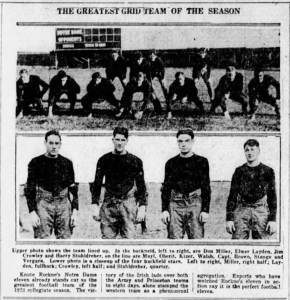

By 1923, Notre Dame football had made great strides towards becoming one of the most prestigious athletic programs in the country. University President Father Matthew Walsh had recently added Princeton to the team’s schedule and moved the Army game to New York [from West Point] where many more Notre Dame alumni could attend. Father Walsh also hoped that the large number of Irish Catholic New Yorkers would make the team their own. These were also significant strides towards creating enough revenue to build a legitimate football stadium at Notre Dame, thus attracting more opponents from more prestigious teams. More importantly, the team was almost unstoppable. [5]

By the time they met Army in October 1923, the Notre Dame players were in peak physical condition and coming off of several Midwestern wins. They quickly wore out Army’s defense, winning 13-0 in front of 30,000 people. [6] Notre Dame’s gridiron battle with Princeton on the Ivy League team’s home turf was even more important. According to Notre Dame football historian Murray Sperber:

The game allowed the Fighting Irish* to symbolically battle their most entrenched antagonists, the Protestant Yankees, embodied by snooty Princeton . . . A large part of Notre Dame’s subsequent football fame, and the fervent support of huge numbers of middle class and poor Catholics for the Fighting Irish, resulted from these clashes with – and triumphs over – opponents claiming superiority in class and wealth. [7]

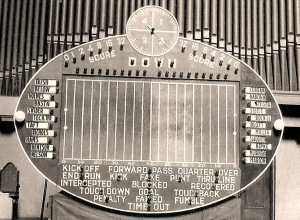

On October 20, the Irish beat the Princeton Tigers handily, 17-0, as Notre Dame students back home watched on the Gridgraph and celebrated in town. [More on “Football Game Watches” here.] The returning players were greeted by their fellow students with a celebration around a blazing bonfire. The students cheered, a band played and speakers, including President Walsh and an Indiana senator Robert Proctor extolled the team. [8]

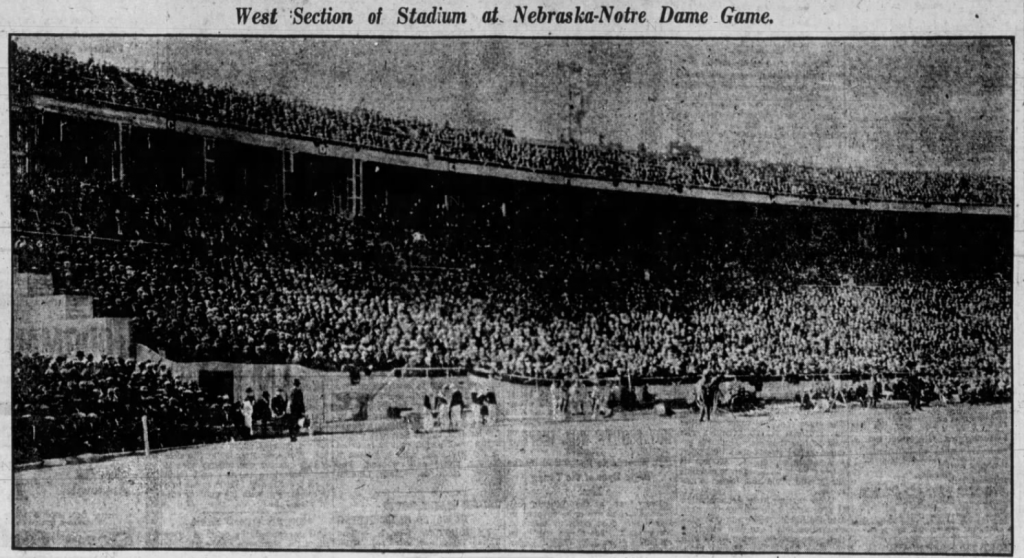

Notre Dame continued their winning streak, beating Georgia Tech 35-7 and Purdue 34-7 over the following two weeks. [9] On November 10, the Irish faced the University of Nebraska Cornhuskers. Unfortunately, the Nebraska team attracted a group of “rabidly anti-Catholic Lincoln fans.” [10] In fact, the Daily Nebraskan, in trying to stir up Cornhusker fans before the big game, wrote that there was a rising “loyalty to Nebraska which bodes ill for the conquering ‘Micks’ from the Hoosier State.” Mick was a derogatory term for an Irishman. The Nebraska newspaper concluded: “LET’S SETTLE THE IRISH QUESTION!”[11]

But, beaten and bruised, stung even by the insults of your hosts, you came off that field with more glory in defeat than many another team has found in victory. [12]

To their credit, Nebraska students, coaches, and administrators condemned the anti-Catholic behavior and issued public and sincere apologies. Nebraska football coach and athletic director Fred T. Dawson wrote the Notre Dame Daily editor: “We are all mortified indeed to learn that the members of the Notre Dame team felt that Nebraska was lacking in the courtesies usually extended to the visiting teams.” Dawson assured the South Bend students that the “many people” heard making “remarks to the Notre Dame team as it withdrew from the field” were in no way connected to the university. He concluded, “our student body and alumni had nothing in their hearts but friendship for Notre Dame.” [13] The Notre Dame Daily graciously accepted Nebraska’s explanation and apology. [14] They had bigger problems at home.

By the spring of 1924, the Klan was thoroughly integrated into Indiana communities and politics. South Bend was an exception. In addition to the Irish Catholic students at the university, St. Joseph County had become home to a large number of Catholic immigrants born in Hungary and Poland. Notre Dame historian Robert E. Burns explained that to the Klan, South Bend was their “biggest unsolved problem.” [15] Klan leader D.C. Stephenson worked to change that, sending in Klan speakers and increasing anti-Catholic propaganda in the widely-circulated Fiery Cross newspaper. He created a plan that was a sort of two-sided coin. On one side, he attempted to legitimize and normalize the hate organization through philanthropic actions and grow its power through politics and law enforcement groups. On the other side, he worked to demonize minority groups such as immigrants and Catholics. [16]

He did not have to work very hard. Burns explained:

The Klan did not invent anti-Catholicism . . . Throughout the nineteenth century anti-Catholicism had been both endemic and respectable in American society. Protestant ministers inspired their congregations with it, and politicians captured votes by employing it. [17]

The Klan successfully used anti-Catholicism as a driving principle because Hoosiers already accepted it. Stephenson hoped that a large Klan rally in South Bend would be the match that lit the powder keg of prejudice. If he could bait a reaction from Notre Dame’s Catholic students and St. Joseph County’s Catholic residents, he could paint them as violent, lawless, un-American immigrants in contrast to his peaceably assembled 100% American Klansmen. This might convince Hoosiers to vote for Klan members or Klan-friendly candidates. On May 17, 1924, just three days before the Indiana Republican Convention, the Ku Klux Klan would hold a mass meeting for its Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois members in South Bend. [18]

Fearful for the safety of their students and local residents, Notre Dame and South Bend officials worked to stop a potentially violent incident. South Bend Mayor Eli Seebirt refused to grant the Klan a parade permit, although he could not stop their peaceful assembly on public grounds.[19] President Walsh issued a bulletin imploring students to stay on campus and ignore the Klan activities in town. He wrote:

Similar attempts of the Klan to flaunt its strength have resulted in riotous situations, sometimes in the loss of life. However aggravating the appearance of the Klan may be, remember that lawlessness begets lawlessness. Young blood and thoughtlessness may consider it a duty to show what a real American thinks of the Klan. There is only one duty that presents itself to Notre Dame men, under the circumstances, and that is to ignore whatever demonstration may take place today. [20]

Father Walsh was right. “Young blood” could not abide the humiliation of this anti-Catholic hate group taking over the town. The Fiery Cross had hurled insults and false accusations at the students. The propaganda newspaper called them “hoodlums,” claimed that Notre Dame produced “nothing of value,” and blamed students for crime in the area.[21] As Klan members began arriving in the city on May 17, 1924, South Bend was ready to oppose them.

The South Bend Tribune reported:

Trouble started early in the day when klansmen in full regalia of hoods, masks and robes appeared on street corners in the business section, ostensibly to direct their brethren to the meeting ground, Island park, and giving South Bend its first glimpse of klansmen in uniform. [22]

Not long after Klan members began arriving, “automobiles crowded with young men, many of whom are said to have been Notre Dame students” surrounded the masked intruders. The anti-Klan South Bend residents and students tore off several masks and robes, exposing the identities of “kluxers” who wished to spread their hate anonymously. The Tribune reported that some Klan members were “roughly handled.” The newspaper also reported that the anti-Klan force showed evidence of organization. They formed a “flying column” that moved in unison “from corner to corner, wherever a white robe appeared.” By 11:30 a.m. students and residents of South Bend had purged the business district of any sign of the Klan. [23]

Meanwhile, Klan leaders continued to lobby city officials for permission to parade, hold meetings in their downtown headquarters, and assemble en masse at Island Park. Just after noon, the group determined to protect South Bend turned their attention to Klan headquarters. This home base was the third floor of a building identifiable by the “fiery cross” made of red light bulbs. The students and South Bend residents surrounded the building and stopped cars of arriving Klansmen. Again, the Tribune reported that some were “roughly handled.” The anti-Klan crowd focused on removing the glowing red symbol of hate. Several young men “hurled potatoes” at the building, breaking several windows and smashing the light bulbs on the electric cross. The young men then stormed up the stairs to the Klan den and were stopped by minister and Klan leader Reverend J.H. Horton with a revolver. [24]

The students attempted to convince Klan members to agree not to parade in masks or with weapons. While convincing all parties to ditch the costumes wasn’t easy, they did eventually negotiate a truce. By 3:30 p.m., “five hundred students and others unsympathetic with the klan” had left the headquarters and rallied at a local pool hall. Here, a student leader spoke to the crowd and urged them to remain peaceful but on vigilant standby in case they were needed by the local police to break up the parade. After all, despite Klan threats, the city never issued a parade license. The plan was to reconvene at 6:30 p.m. at a bridge, preventing the Klan members from entering the parade grounds. In the end, no parade was held. Stephenson blamed the heavy rain for the cancellation in order to save face with his followers, but the actual reason was more sinister. [25]

Stephenson knew that he had been handed the ideal fuel for his propaganda machine. Using a combination of half truths and blatant lies, he could present an image of Notre Dame students as a “reckless, fight-loving gang of hoodlums.” [26] The story that Stephenson crafted for the press was one where law-abiding Protestant citizens were denied their constitutional right to peacefully assemble and were then violently attacked by gangs of Catholic students and immigrant hooligans working together. They claimed that the students ripped up American flags and attacked women and children. [27] The story picked up traction and was widely reported in various forms. In the eyes of many outsiders, Notre Dame’s reputation was tarnished. Unfortunately, they would have to survive one more run-in with the Klan before they could begin to repair it. [28]

The press they garnered from the clash in South Bend had been just what Stephenson ordered. He figured one more incident, just before the opening of the Indiana Republican Convention, would convince stakeholders of the importance of electing Klan candidates in the face of this Catholic “threat.” Local Klan leaders just wanted revenge for the embarrassing episode. [29] Only two days later, on Monday, May 19, the Klan set a trap for Notre Dame students. Around 7:00 p.m. the lighted cross at Klan headquarters was turned back on and students began hearing rumors of an amassing of Klan members in downtown South Bend. The South Bend Tribune reported, “Approximately 500 persons, said to have been mostly Notre Dame students, opposed to the klan . . . started a march south toward the klan headquarters.” [30] Meanwhile, Klan members armed with clubs and stones spread out and waited. When the students arrived just after 9:00 p.m., the Klan ambushed them. The police tried to break up the scene, but added to the violence. By the time university leadership arrived around 10:00 p.m., they met several protesters with minor injuries. The students were regrouping and planning their next move; more violence seemed imminent. Climbing on top of a Civil War monument, and speaking over the din, Father Walsh somehow convinced the Notre Dame men to return to campus. The only major injury sustained was to the university’s reputation. [31]

Some secondary sources have claimed that it was the Notre Dame football team that led the flying columns and threw the potatoes that broke the lit-up cross. These sources claim that that the football team were leaders in these violent incidences. [32] While it is possible that the players were present at the events, no primary sources confirm this tale or even mention the players. It’s a good story, but likely just that.

But there is a better story here. It’s the story of how the 1924 Notre Dame football team stood tall before a country tainted by prejudice as model Catholics and American citizens of immigrant heritage. It’s the story of how they polished and restored the prestige and honor of their university. It’s the story of how one team established the legacy of Notre Dame football and fought their way to the Rose Bowl.

This is the end of Part One of this two-part series. See Part Two to learn about the historic 1924 Notre Dame football season, the university’s media campaign to restore its image, and the players victory on the gridiron and over its xenophobic, anti-Catholic detractors.

Notes and Sources

*The University of Notre Dame did not officially accept the name “Fighting Irish” for their athletic teams until 1925. I have felt free to use it here as students, alumni, and newspapers had been using “Fighting Irish” at least since 1917.

Further Reading:

Robert E. Burns, Being Catholic, Being American: The Notre Dame Story, 1842-1934 (University of Notre Dame Press, 1999); Murray Sperber, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993, reprint, 2003)

Notes:

[1]Robert E. Burns, Being Catholic, Being American: The Notre Dame Story, 1842-1934 (University of Notre Dame Press, 1999), ix.

[2] “For What Purpose?” Huntington Press, October 1, 1922, 1, Newspapers.com. This editorial decries the Klan trying to establish itself in South Bend, noting the city’s history of tolerance around the university.[3]“Class Orators Awarded Place,” Notre Dame Daily, May 20, 1923, 1, University of Notre Dame Archives;“Washington’s Birthday,” Notre Dame Daily, February 21, 1924, 2, University of Notre Dame Archives.

[4] Jill Weiss Simins, “‘America First:’ The Ku Klux Klan Influence on Immigration Policy in the 1920s,” Untold Indiana.

[5] Murray Sperber, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993, reprint, 2003), 138-139.

[6] “Surprises in Indiana Foot Ball Results,” Greencastle Herald, October 15, 1923, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[7] Sperber, 147-8.

[8] “Irish Victory Is Celebrated,” Notre Dame Daily, October 23, 1923, Notre Dame Archives; Sperber, 148-9.

[9] Thomas Coman, “Rockmen Conquer Georgia Tech, 35-7,” Notre Dame Daily, October 28, 1923, 1, Notre Dame Archives; Thomas Coman, “Irish Gridders Beat Purdue, 34-7, Notre Dame Daily, 1, Notre Dame Archives.

[10] Sperber, 149.

“It Shall Be Done,” Daily Nebraskan in “What They Say,” Notre Dame Daily, November 10, 1923, 2, Notre Dame Archives.

[12] “To Those Who Can Read,” Notre Dame Daily, November 17, 1923, 2, Notre Dame Archives.

[13] “Letter Box,” Notre Dame Daily, November 27, 1923, 2, Notre Dame Archives.

[14] “Settled,” Notre Dame Daily, December 15, 1923, 2, Notre Dame Archives.

[15] Burns, 278.

[16] Ibid., 265-280, 302.

[17] Ibid., 267-9. Burns also explains the reasoning Klansmen and others employed to justify their anti-Catholic prejudice.

[18] Ibid., 303-5.

[19] “Heads, Not Fists,” Notre Dame Daily, May 17, 1924, 2, Notre Dame Archives.

[20] “Yesterday’s Bulletin,” Notre Dame Daily, May 18, 1924, 2, Notre Dame Archives.

[21] “Notre Dame Students Stage a Riot,” Fiery Cross, March 16, 1923, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[22-25] “Klan Display in South Bend Proves Failure,” South Bend Tribune, May 18, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com.

Based on first-hand descriptions in the article, its clear that the South Bend Tribune reporter was on the scene during the May 17 event. Thus, this article proves the most reliable of the many that ran in newspapers throughout the country. The Tribune‘s report, unlike many later reports in other papers, was untainted by subsequent Klan propaganda. Thus the descriptions of the event in this post are drawn from this article only, though others were consulted.

[26] “Arrogance of Notre Dame Students Gone,” Fiery Cross, June 13, 1924, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Burns, 314-316.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Mayor Seebirt Moves Toward Peace in Klan War,” South Bend Tribune, May 20, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com.

[31] Ibid.

[32] In his 2004 book Notre Dame vs. the Klan, Todd Tucker tells a fictionalized version of the May 17 incident using a composite student character. [Tucker named this fictional character named Bill Foohey after an actual Notre Dame student who appeared in a photograph wearing one of the confiscated Klan robes, but left no further record of his involvement]. In Tucker’s version of the incident, Notre Dame quarterback Harry Stuhldreher threw a potato in a “perfect arc” to hit the “lone red bulb” remaining in the cross at Klan headquarters. Stuhldreher hit it and the crowd cheered like it was a football game. Tucker wrote in his author’s note at the beginning of the book that he had “taken a great liberty” in the creation of Foohey and that he had “extrapolated historical events to bring out the drama of the situation.” However, several other sources have now repeated Tucker’s version as factual as opposed to fictionalized. For a thoroughly researched, factual account of events, see Chapter 9 of Robert Burn’s Being Catholic, Being American: The Notre Dame Story, 1842-1934.