On May 14, 1914, Hoosier speedster Erwin G. Baker arrived in New York City after driving over 3,000 miles across the country on his Indian motorcycle. Baker’s run from San Diego to New York City in eleven and a half days not only broke the previous transcontinental record set by Volney E. Davis in 1911, it shattered it by almost nine days (Davis’s record was 20 days, 9 hours, and 1 minute). Baker’s feat, coupled with several other speed and distance records he set during this period, quickly earned him the nickname “Cannon Ball;” a moniker he would proudly carry with him for the rest of his life.

Erwin G. Baker was born in southeastern Indiana in 1882 and moved to Indianapolis with his family sometime between 1893 and 1894. In the early 1900s, he worked as a machinist in the city and performed a bag punching routine on vaudeville stages throughout the country. The act required Baker to try and keep a certain number of punching bags going at the same time. In January 1909, the Indianapolis Star lauded him as a “champion bag puncher” and noted that he was “regarded as one of the best in the country.” According to the article, Baker was preparing to compete against Harry Seeback for the national title, contending that he could keep twelve bags going at once, as opposed to Seeback’s eight.

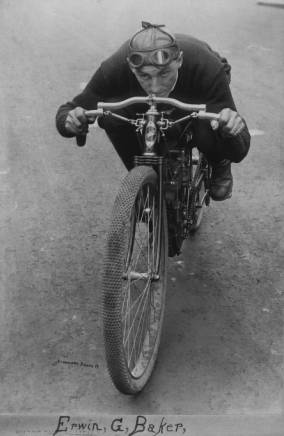

While Baker may have gained some recognition for his bag punching routine, it was his interest and skill riding motorcycles that earned him early fame and jump started his career. In the summer of 1909, Baker was one of many drivers to compete at the newly opened Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

The first motorcycle races – which predated automobile races at the famous track – were held in mid-August under the sanction of the Federation of American Motorcyclists (F.A.M.). Baker competed in the ten-mile amateur championship. According to the Indianapolis Star, the event lacked a large number of entries due to racer Jake DeRosier’s recent accident on the unpaved gravel track and fear on the part of some of the drivers about being badly injured themselves. Baker, already regarded as a daredevil racer and “rider of great skill and nerve,” took home first place in the event in a time of 11:31 1-5. Just two months later, he claimed two more first place wins, one second place win, and two third place wins at a series of races in Dayton, Ohio.

Over the next few years, Baker traveled all over the country, competing in a wide variety of motorcycle races and setting many new track records.

In early 1913, the Indianapolis Star reported that he had departed on a motorcycle tour of the southern United States, as well as Cuba, Jamaica, Panama, and Mexico. The trip was said to cover some 12,000 miles. Baker was constantly testing out the limits of his Indian motorcycle and other vehicles he drove, challenging how far he could make it on a tank of gas or how long he could go without experiencing mechanical problems. Companies frequently hired him or sought his help to test and promote their brands. For instance, during Baker’s motorcycle tour of the South, he served as an experimenter for the U.S. Tire Company and tested the durability of the company’s tires over the course of his journey. Later in life, many motorsport companies would seek his endorsements as the public came to associate him with professional integrity and a sense of nostalgia for early racing.

In 1914, Baker set out to test himself once again. This time, his goal was to break the transcontinental record set by Volney Davis a few years earlier. Rather than departing from San Francisco as Davis had, Baker made San Diego his starting point. In a post card from Baker to William Waking of Waking and Company mailed May 1, 1914, he wrote:

Dear Friend Waking:

Am leaving San Diego, Cal., May 3. Will wire you just before my arrival at Richmond and ask you to assist in guiding me through your city. I’m making an effort to break transcontinental record which stands 20 days, 9 hours, one minute. Such assistance would keep me from losing time.

Yours truly,

E.G. Baker

The trek required the Hoosier speedster to travel through twelve states and across all manner of roads. In the early twentieth century, few roads were paved and the standard highway numbering system we are so accustomed to today was not yet established. While Baker often intentionally sought out demanding, primitive mountain roads or desert paths in order to prove the efficiency of the vehicle he was promoting, even the roads of his mostly flat home state of Indiana would have presented a challenge in these years. Baker also had to battle the weather in his transcontinental run, as his route took him from the scorching desert heat to colder mountain temperatures. The Indianapolis News said it best in a May 5, 1914 article, noting “the ride will not be a picnic.”

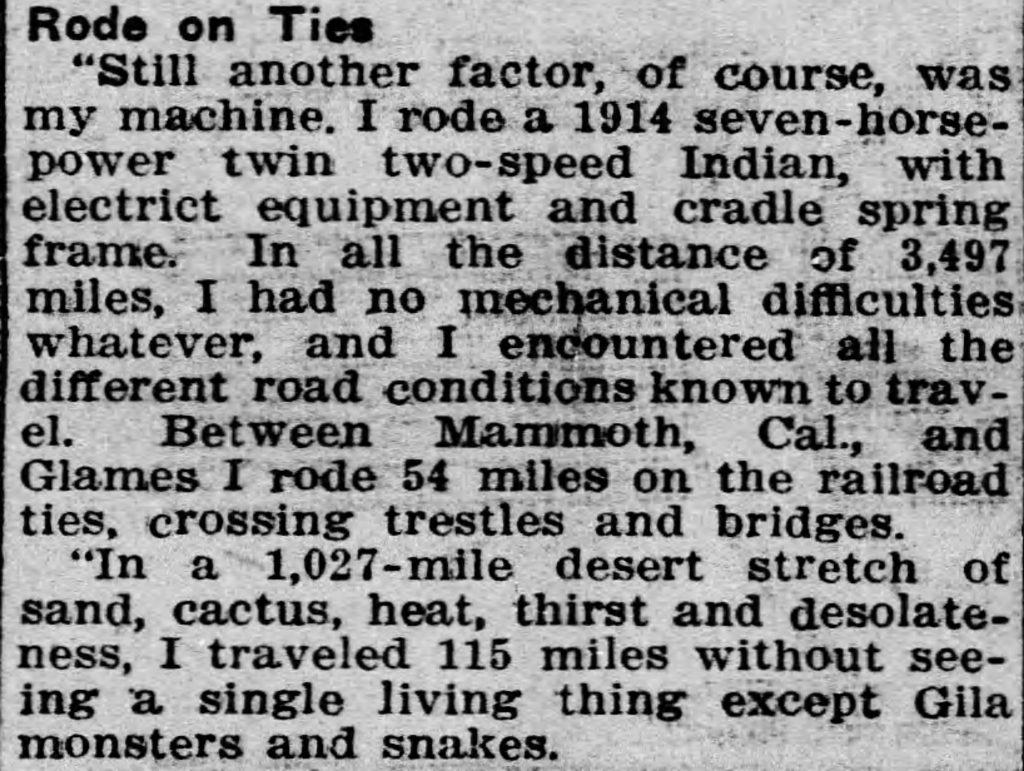

Baker was undeterred and well prepared. Newspaper accounts report that he laid out his route ahead of time, planning what roads and towns to travel through and even planting tanks of gas ahead of him in remote areas so as to avoid fuel trouble. Working with a weather expert, he also considered weather conditions for the past decade to determine what month would be best for his trip. He traveled light. According to the Indianapolis News, Baker carried two extra inner tubes, a short and long chain, a small Graflex camera, a half-gallon canteen, and a .48 caliber revolver for protection. His Indian motorcycle was a “two-speed model, equipped with electric lights and speedometer.”

The F.A.M. sanctioned the ride and, as a result, Baker wrote nightly reports updating the organization on his progress and offering details about his journey. Newspapers across the country also covered the story and helped track his route. The first leg of his trip, one which Baker would describe as one of the worst due to the sandy desert and high temperatures, took him from San Diego, California to Phoenix, Arizona. On May 7, the Albuquerque Journal reported that he passed through Albuquerque, New Mexico the previous afternoon and, after a short stay, continued on to Santa Fe, bringing his total mileage that day to just over 350. From Santa Fe, Baker traveled through Las Vegas, New Mexico on to La Junta, Colorado before making it into Kansas. He reached Topeka, Kansas seven days and six hours after starting his journey in San Diego and was well on his way to breaking Davis’s previous transcontinental record.

However, Baker encountered some trouble at this point in his trip. According to the Topeka Daily Capital, while road conditions in Kansas surpassed those of the desert, Baker had to contend with seven nail punctures along this leg and hit a dog that had crossed his path, causing him to topple from his motorcycle and the machine to fall. Baker injured his elbow and knee, but did not allow the incident to discourage him. He made it to Indianapolis on May 12 and even stopped for a quick dinner at home before continuing on. He had been on the road a little over nine days when he made it to his home state and had already covered 2,600 miles. It’s no wonder that the Indianapolis News referred to him as “Here-He-Comes-There-He-Goes Baker.”

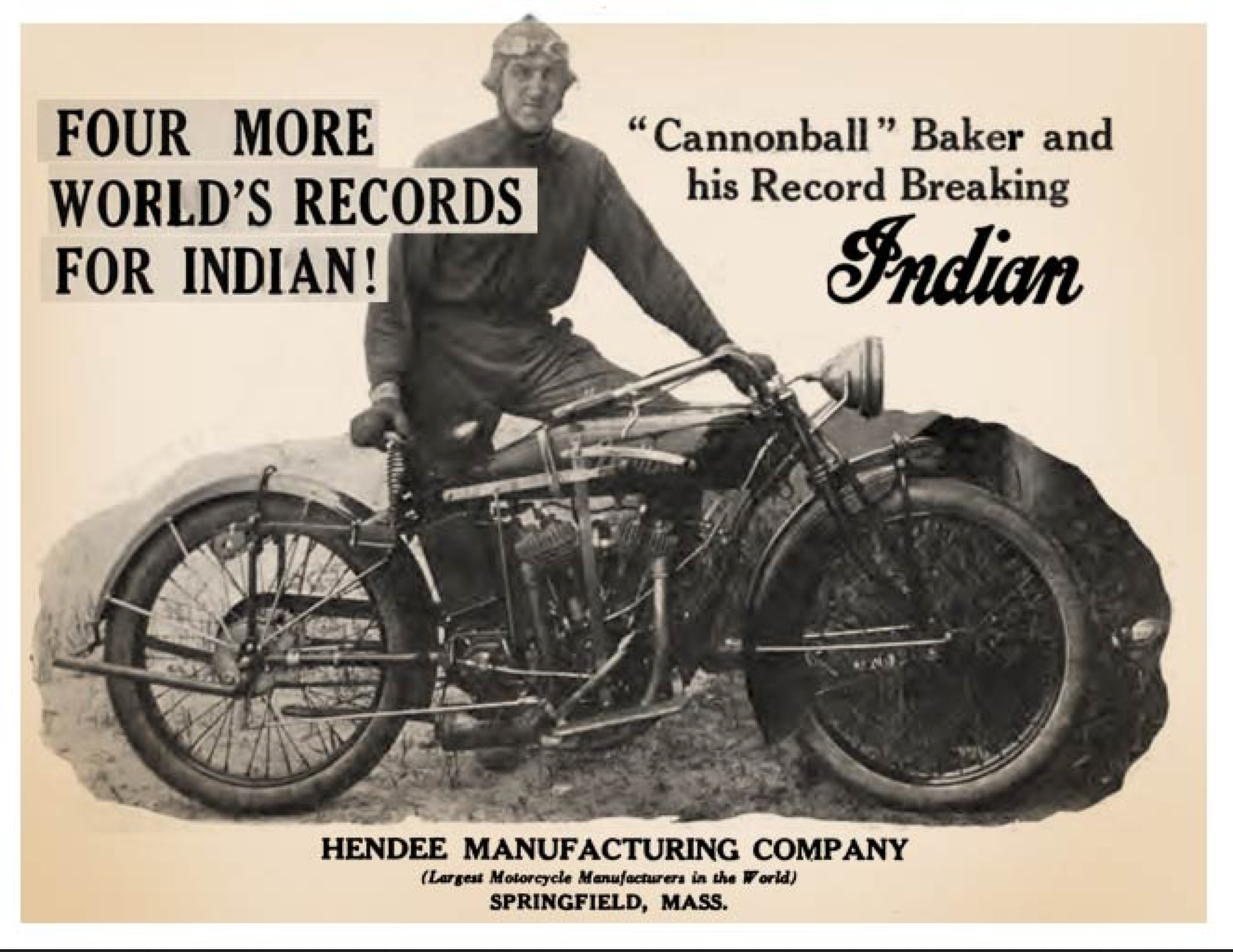

Baker arrived in New York City on May 14, having driven well over 3,000 miles. The 11 day trip effectively shattered Volney Davis’s record by almost nine full days. The Indianapolis News rightly wrote on May 15 that the trek represented “not only the sturdy qualities of [Baker’s] machine, but the endurance of the rider.”

Reflecting on his record-breaking run in the days and weeks following, Baker credited his preparation and calculation before the trip as a large factor contributing to his success. He also praised his Indian motorcycle, noting that throughout the entire journey, which included fording streams and riding on railroad ties, he experienced no mechanical troubles. He noted that his batteries needed no recharging and that the original light bulb on the machine still burned brightly. According to Baker:

Four mountain ranges were negotiated. At one point at the northern end of Arizona, I climbed from 200 feet below sea level to an altitude of 9,647 feet into the mountain snows. It was in this mountain work that the two-speed showed its supreme qualities. My [brake] power, too, in making the precipitous descents of the winding mountain trails, never failed me for a moment. If it had I might not be able to tell this story.

I am a Hoosier, and the welcome and encouragement my home state gave me as I passed from town to town was a generous and appreciated demonstration.

The 1914 transcontinental run was just one of numerous record-setting trips Baker would make in a variety of vehicles from the early 1900s through the early 1940s. In 1915, he set the “Three Flags record” for “touching three countries” during a run from Canada to Mexico on an Indian motorcycle. According to the Wichita Daily Eagle, he “crashed down the Pacific Coast . . . at a speed faster than any man ever rode before on a motorcycle on any long journey.” It took him three days, nine hours, and fifteen minutes despite facing mountainous terrain and even passing through forest fires. It is not surprising that reporters christened him “Cannon Ball” Baker, as he barreled through towns and states at ever-increasing speeds. Baker died in 1960, but his legacy and contributions to motorsports continue to live on.

In the fall of 2017, the Indiana Historical Bureau will help commemorate “Cannon Ball” with a historical marker near his former home across from Garfield Park in Indianapolis. The marker celebrates the pioneer racer and test driver, while also paying tribute to his 1922 Indianapolis 500 run, in which he finished in 11th place, and his role as the first commissioner of NASCAR. Follow IHB’s Facebook page and Twitter for information about the marker dedication.