John Chapman, also known as Johnny Appleseed, serves as an example of a part of the religious fervor on the western frontier in the years before the Civil War. The legends and tales about him that grew even in his own lifetime rivaled those of his contemporaries, Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone. Like them, Chapman’s career in the wilderness as a preacher and Good Samaritan quickly got caught up in the American imagination.

Johnny Appleseed had been on the frontier for several decades before coming to Fort Wayne, possibly as early as 1822. Already many stories were told of this gentle man’s propagation of fruit trees in odd plots of land all over the Pennsylvania and Ohio wilderness, his love of wildlife, and the awe in which American Indians regarded him as a powerful medicine man.

He repeated the Bible verse Song of Solomon 2:5, which stated “refresh me with apples.” Johnny Appleseed declared “with apples shall men be comforted in the wilderness of the West.” A holy man he was, for his principal aim was to bring, “some news right fresh from heaven” as he read from the Beatitudes to the settlers he visited in cabins in the forest. He told them of the spiritual happiness he enjoyed through the teachings of the Church of New Jerusalem. Ironically, the apples produced were not like the sweet apples we eat today, and therefore the fruit was more likely to be used for hard cider. This explains why many of the orchards he planted were destroyed during Prohibition.

One eyewitness described Johnny Appleseed’s appearance when he came to Fort Wayne as:

“simply clad, in truth clad like a beggar. His refined features told of his intelligence, even though seen through the gray stubble that covered his face since he cut his hair and beard with scissors. Johnny was serious, his speech clean, free from slang or profanity. He traveled on foot – sometimes with just one shoe or two different kinds of boots.”

Some descriptions have him wearing his cooking pot for a hat, at times with other parts of hats – the crown or the brim – on top of his tin cap. Other biographers claim that because his mush-pot hat did not protect his eyes from the bright sun well enough that he fashioned one made of pasteboard with a large peak in front. Although his eccentric appearance occasionally caused anxiety or even alarm in some people, by and large, he was well liked for his sincere and kind ways.

Exceptionally strong for his tall slim frame, one pioneer observed that Johnny Appleseed was able to get more work done clearing the forests in one day than most men could finish in two. Above all else, however, he was appreciated for his great ability to tell stories about his church, of his many adventures on the frontier, his narrow escapes in the wilderness, his interactions with American Indians, and his association with the wildlife of the Midwest, from bears to wasps.

Johnny Appleseed showed a great reverence for all life, including the lowly insects. In fact, he became a vegetarian later in life. One story often told was that when he was being stung by a hornet that had crawled into his shirt, he carefully removed his shirt to allow the creature to go on its way unharmed rather than kill the stinging nuisance. On another occasion he put out his evening camp fire to avoid the possibility of the moths being destroyed in the flames. He was known to have purchased an aged horse from a pioneer who was continuing to put the creature to work, in order that the animal could spend its last days peacefully at pasture. A settler once described him saying that he was like, “good St. Francis, the little brother of the birds and the little brother of the beasts.”

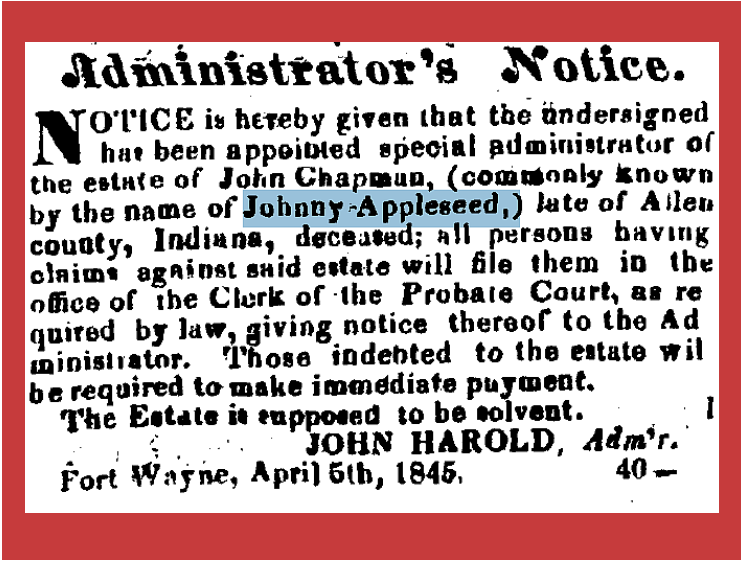

Johnny Appleseed died in 1845 at the age of 71. He had been protecting his saplings from some cows that had broken down the fence of one of his orchards just north of Fort Wayne. He was overcome by his exertions and succumbed to what the people of the time called the “winter plague.” He was buried along the St. Joseph River and the old feeder canal bed on the Archer farm, but the actual site is not known today; a commemorative marker** sits atop the hill in present-day Johnny Appleseed Park, which was once the Archer family cemetery. Each year during the Fort Wayne festival that bears his name, visitors remember the comfort John Chapman brought to the west, for around his memorial children fondly place their gifts of apples.

**This marker is not associated with the Indiana Historical Bureau State Historical Marker Program.

Learn more about Johnny Appleseed and his influence on cultural history with William Kerrigan’s book, sold at IHB’s Book Shop.