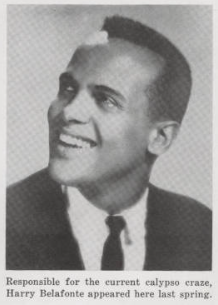

In 1956, Black activist Harry Belafonte was one of the top performers in the United States and his album, Belafonte, reached #2 on the Billboard Chart. When he performed two shows of “Sing, Man, Sing” at the Purdue University Hall of Music on May 5, it was a major hit. Before the first performance, Belafonte visited Purdue’s famous drinking establishment, Harry’s Chocolate Shop. However, proprietor Harry J. Marlack refused to serve him due to the color of his skin.

Born in Harlem to Jamaican parents, Belafonte experienced discrimination throughout his life. In 1944, while serving in the U.S. Navy, Belafonte was denied entry to New York’s famous Copa Cabana because he was Black. When Belafonte achieved stardom in the 1950s, the Copa Cabana offered him a lucrative contract to perform there. He infuriated the owner by spurning the offer, citing the discrimination he faced at their door years earlier in his decision.

In Spring 1956, Belafonte met Martin Luther King, Jr. for the first time in the basement of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Belafonte committed to “help [King] in any way I could. And for the next twelve years, that’s what I did.”[i] When he concluded the first show at Purdue, Belafonte kept his promise to King and addressed the audience about the discriminatory act and what he thought of it. His words angered Purdue officials and the campus buzzed. While Purdue students and staff talked about the incident at Harry’s Chocolate Shop and Belafonte’s speech for weeks afterward[ii], nothing was written about the incident. This prompted a Ph.D. student, David Caplan, to write a letter to the editor of The Exponent, Purdue’s student newspaper. Caplan wrote:

Many Purdue students and staff members have been talking about a recent incident that took place in ‘Harry’s Chocolate Shop’ when Harry Belafonte and his troupe were in town. Why has no mention been made of this in the Exponent? Certainly an incident of such scope deserves at least a news item, if not an editorial. Burying one’s head in the sand does not change the facts that have occurred. Why has this story not been reported?

The Exponent editor responded to Caplan by writing, “the Exponent has followed and will continue to follow the accepted journalistic practice of not publishing ‘cold’ news or facts that have been distorted by personal opinion or hearsay. The Exponent staff refuses to yield to ‘rabble-rousers’ or free-publicity seekers.”[iii]

Behind the scenes, Purdue University officials had zero tolerance for Belafonte’s civil rights message. In a 1977 interview with the Lafayette Journal & Courier, former director of Purdue Musical Organizations, Al Stewart, talked about many famous people he had met during his long career. Of Belafonte, Stewart opined:

He finished a 7 p.m. show with an angry jab at racial discrimination at a local drinking place. I warned him never to do that again or he’d never get another booking anywhere in the U.S. Second show, Dr. Hovde (Purdue President Frederick L. Hovde) and I sat in the front row and tape-recorded the whole thing as evidence if we needed it. It was a beautiful show.

Stewart’s comments demonstrated stunning hubris. Belafonte was on top of the entertainment world in 1956. He had the #2 album in the United States. In June, he released a second album, Calypso, that spent a record ninety-nine weeks on the Billboard Chart. He headlined Broadway shows and top-tier venues across the country. He played the Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles and the Palmer House in Chicago. He broke Lena Horne’s attendance record at the Venetian Room in San Francisco, and broke the color barrier and Frank Sinatra’s attendance record at Waldorf’s Empire Room in New York City. Furthermore, it’s impossible to imagine Stewart belittling Sinatra or Elvis Presley—Belafonte’s peers at the time.

By the time Stewart made his remarks in 1977, the Civil Rights Act had become law thirteen years earlier. Belafonte had recorded a campaign ad for John Kennedy, mediated between Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show ten times, hosted the Tonight Show for a full week, had four gold records, starred in movies, and was a world-renowned civil rights leader. For Stewart to think he could have curtailed this superstar’s career is laughable, had it not been so bigoted. In response to racism, university officials told a Black man “Shut up and sing.”

Harry Belafonte would refuse to “shut up and sing.” Rather, upon his return visits to Indiana, he used his voice to advance racial justice. He donated significant funds to Gary candidate Richard Hatcher’s mayoral campaign and vocalized his support for the unlikely candidate in national media outlets. Belafonte’s efforts helped make Richard Hatcher one of the first Black mayors of a major American city. In 1972, Belafonte returned to Gary to perform at the unprecedented National Black Political Convention, taking the opportunity to implore the massive audience to engage in political reform.

In January 2017, Belafonte returned to Purdue University, serving as keynote speaker for the university’s Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s celebration, themed “The Fierce Urgency of Now: Where Do We Go From Here?” At age 89, he knew his life’s work was unfinished and he delivered a rousing speech on justice, civic engagement, and meaningful art. Audience member Sandra Sydnor told the Journal & Courier “’I was overwhelmed by his presence. . . . We were just staying rooted in spot, not wanting to leave after he left because of his persona, because of his spirit.’” Belafonte passed away April 25, 2023, but this spirit would endure, along with his legacy of racial justice and equal rights activism.

* This piece will be featured in the author’s upcoming book, Dispatches from a Northern Hoosier.

Notes:

[i] Harry Belafonte and Michael Shnayerson, My Song: A Memoir (New York: Penguin Random House, 2011), 150.

[ii] Conversation between the author and All-American football player Bernie Flowers, 1995.

[iii] The Purdue Exponent, May 23, 1956.

[iv] Lafayette Journal & Courier, November 13, 1977.

Stewart’s judgment is questionable. Belafonte referred to Sing, Man, Sing as “my one indisputable career bomb.” My Song: A Memoir, 142.