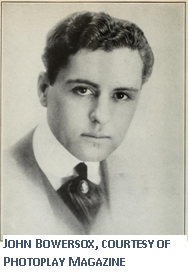

Many dismiss movies made during the silent film era (1885-1930) as farcical or irrelevant. However, this period of great discovery and innovation laid the foundation for modern film-making techniques. One early contributor to this burgeoning new art form was Hoosier actor John Bowersox. He made over ninety films during his career and was among those first honored with stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. His versatility and athleticism enabled him to become a leading man in a variety of roles and genres. Off-screen, Bowersox was an extreme sports enthusiast who enjoyed racing his automobile, airplane, and yacht during a novel time for those sports.

Born circa 1884,[1] John Bowersox grew up in the small town of Garrett, Indiana, not far from Fort Wayne. Six feet tall and naturally athletic, Bowersox played football on a local Garrett team.[2] As a young man, he could often be found sailing his boat on nearby Lake Wawasee, the largest natural lake in Indiana. As early as fifteen, he began acting locally in amateur plays. His parents encouraged him to become a lawyer and John enrolled in nearby Huntington Business College. However, John Bowersox was destined for something completely different.

Bowersox continued to act while attending college and he caught the eye of local stock company owner, C. Garvin Gilmaine, who took Bowersox under his wing and eventually recommended him to a touring company performing A Royal Slave.[3] Turning his back on college, John signed an acting contract and left Garrett for rehearsals in Coldwater, Michigan in July, 1904.[4]

As a demonstration of support, his father equipped him with $450 worth of clothes and a trunk that his co-workers joked was worth more than all the show props combined. Bowersox recalled his father’s parting words in an interview with Photoplay Magazine, “If you don’t make [a go of it], come home.”[5] That $450 investment George Bowersox made in his son turned out to be a good one.

The part he played as a Mexican soldier in A Royal Slave introduced Bowersox to a world he could have only dreamed of as a small-town kid. It led to more roles and bigger parts and, by 1912, Bowers had dropped the “ox” from his name and worked as an actor in New York City. [6] Many of his early performances came by way of his relationship with William A. Brady, a prolific producer of both stage and screen.[7] Under his guidance, Bowers made his Broadway debut in Little Miss Brown on August 29, 1912.[8]

When Bowers was working in New York theater, film studios in and around the city dominated the American motion picture film industry. By today’s standards, “silent era” films can seem campy and amateurish. The acting was often melodramatic and unnatural, a by-product of stage performances. However, a century ago this entertainment medium was every bit as creative and innovative as modern day modes of expression like virtual reality and TikTok.

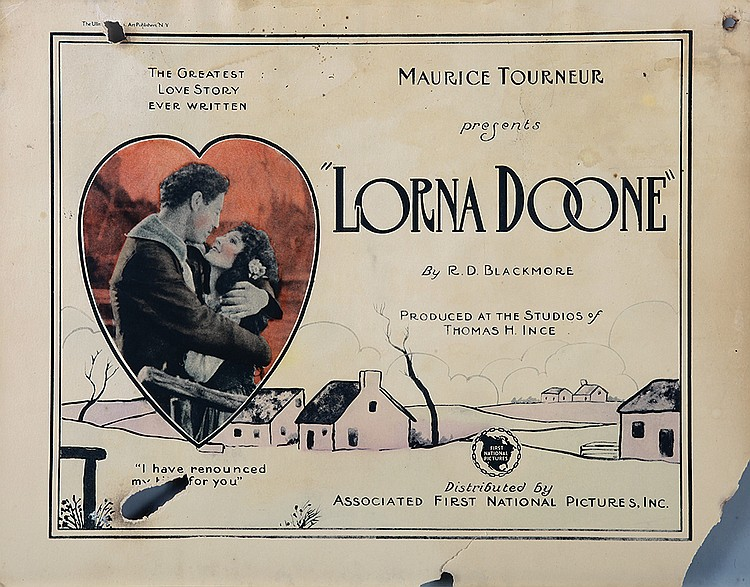

As the scale of production increased, the larger studios on the West Coast began dominating the film industry and Bowers eagerly followed the work, moving back and forth between New York, Chicago, and California.[9] It’s impossible to know precisely how many films Bowers made. Early film stock contained highly volatile nitrates that were subject to deterioration at best, and combustion at worst. Some sources estimate that seventy-five percent of early films are forever lost to either decay or disposal.[10] Bowers’s first known credit appears in the short film The Baited Trap (1914), in which he played a criminal.[11] He made two more films that year including one with Tom Mix. It wasn’t long before “John Bowers” was a leading man. He is officially credited with appearing in over ninety films, including Lorna Doone (1922), The Sky Pilot (1921), When a Man’s a Man (1924), and Chickie (1925). His rugged good looks and natural athleticism allowed Bowers to play many different roles.

Although often the love interest, Bowers played heroes, gangsters, cowboys, businessmen, soldiers, and lawyers. He acted in many genres including drama, musical, comedy, romance, crime drama, adventure, action, and westerns. He worked with most of the early silent film stars, such as Mary Pickford, Will Rogers, Lon Chaney, Bela Lugosi, and Richard Dix. In 1960, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce honored him with one of the inaugural stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[12] However, acting did not define John Bowers.

Always a bit of daredevil, Bowers took pride in doing his own stunts, believing the audience would appreciate him more if they saw him risking life and limb.[13] Early in his stage career, while acting in A Royal Slave, his over-enthusiastic dueling performance resulted in a sword-jab to his eye, causing serious injury.[14] Years later, while making the film When a Man’s a Man (1924), he broke his leg trying to bull-dog a steer.[15]

He was always athletic and believed that staying physically fit was essential to happiness.[16] As a teenager, he built his own 21’ sailboat that he sailed around Lake Wawasee in northern Indiana. Bowers became so adept at maneuvering it that he would sometimes “turn turtle” just to exasperate his parents watching from shore.[17] Sailing would become central to Bowers’s life. After achieving some success in New York, he purchased a 70’ racing schooner, the Uncas, which he enjoyed sailing up the Hudson River.[18] Sometime in the early 1920s, his friend Doc Wilson sailed it from New York to California in ninety days.[19] Later, Bowers would take his Hollywood friends out for weeks at a time.[20]

An early adopter, Bowers embraced new technology. He became enamored with automobiles and was a known speedster around Los Angeles. In 1924, he took racing lessons from professional driver Ralph De Palma and even entered the 250-mile Thanksgiving Day race at the Ascot Speedway in LA.[21] In addition to sailing and racing cars, Bowers became an accomplished pilot and even customized his own racing plane. In 1927, Bowers won first place on both days of the Santa Anna air races with his plane, the Thunderbird.[22]

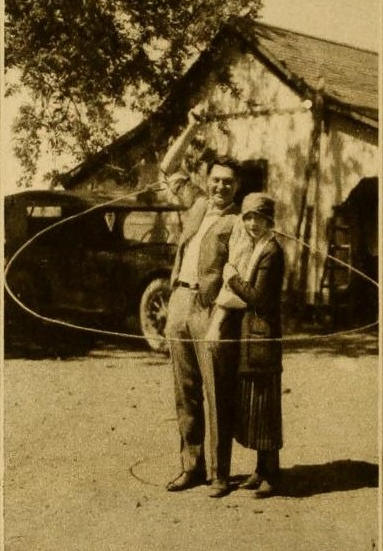

In the early decades of the 20th century, the Western genre began to take off and many film roles required athleticism. Bowers, who was reportedly, “an excellent horseman, can swing a mean lariat, and can bull-dog a steer like a hardened plainsman,” landed many plum roles.[23] The exuberance in which he lived life made for great press. Publicists, either on behalf of the studios or hired by actors for a percentage of their income, carefully crafted the images of movie stars. They arranged appearances, set up photo shoots, and provided copy to trade magazines and newspapers eager to report the off-screen lives of the Hollywood elite. [24]

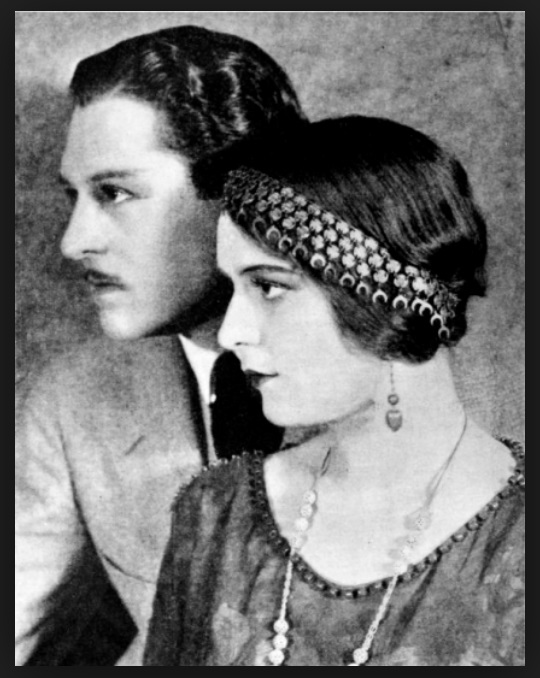

His third wife Marguerite De la Motte was also a silent film star. [25] De la Motte and Bowers co-starred in the film What a Wife Learned (1923), where they developed a friendship. For quite a while, fans and media speculated about their relationship and, according to most sources, Bowers and De La Motte married in 1924.[26] The couple often entertained and sometimes amused their guests with an exhibition of Bowers’ shooting prowess. De La Motte would place an object on her head and John would shoot it off, an offer he made to anyone willing to participate.[27] It is unclear how many reports about John Bowers are true. Many newspaper accounts reported what he was going to do rather than what he actually did. It’s possible that some accounts of Bowers have been exaggerated. Self-promotion and exaggeration were just as common then as they are today. One thing is certain; John Bowers embodied the spirit of carpe diem.

Bowers worked steadily during the 1920s, but like many silent film stars, he was unable to make the transition to “talkies”. Actors struggled to succeed in the era of sound for many reasons. Sometimes their voices did not match their screen persona, possibly due to an accent or the pitch of their voice. Some actors relied on constant direction that was not possible with the introduction of sound. For whatever reason, by 1927 Bowers’s film career was in decline. To make matters worse, around 1930 John and Marguerite likely separated.[28]

The last movie Bowers made was Mounted Fury (1931). By then his drinking had become a problem. Bowers was only forty-five-years-old, but his life was unraveling. A few years later, he returned to Indiana and wrote a weekly fictional serial for the local newspaper, the Garrett Clipper. [30] The serial was a lighthearted coming-of-age story of a small town kid who made good. The protagonist, John Wright, was affable, ambitious and, “If he had fallen into a sewer he would have come out with a bouquet in his hand.” Many of the characters would probably have been familiar to Garret residents, and the serial ran from March until August of 1936.

While in Indiana, John had been caring for his long-ill mother, Ida, in nearby Syracuse when she passed away in July of 1936.[31] Given the new void in his life, John decided to give acting another try. He heard that his old friend Henry Hathaway was directing a film with Gary Cooper and hoped there might be a part in it for him. So, he went back to LA one last time.

The morning after finding out that Hathaway was unable to offer Bowers a part in his movie, Bowers rented a small sailboat in Santa Monica. Two days later, on November 17, 1936, his body washed ashore in Malibu. The coroner reported the cause of death as “Drowned as a result of suicide – jumped off sail boat.” The boat was later recovered adrift.[32] His sister, with whom he was staying at the time, reported that he had recently become despondent.[33]

Although nobody knows what was on the mind of John Bowers when he went overboard, most believed he died by suicide. His mother had recently passed away, his acting career was floundering, and his drinking had become problematic. Despite such a tragic ending, this Hoosier left behind a legacy as a prolific film actor and adventurer.

Notes:

[1] The exact date of Bowers’s birth is questionable. Census records, newspaper articles, and magazine stories report his date of birth differently, but generally around 1885. The DOB from his death certificate is the only official record. “California, County Birth and Death Records, 1800-1994,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9SF-P9BR-Y?cc=2001287&wc=SJ5X-JWG%3A285174601%2C285330201 : 22 August 2018), Los Angeles, Death certificates 1936, no. 10100-12041, image 31 of 2142, California State Archives, Sacramento.

[2] “Local and Personal,” Garrett Clipper (Indiana), October 15, 1903, 5, Newspapers.com.

[3] “John Bowers Receives Contract for Royal Slave Company,” Huntington Herald (Indiana), May 20, 1904, 4, Newspapers.com.

[4] “John Bowers Receives Contract for Royal Slave Company,” Huntington Herald, May 20, 1904, 4, Newspapers.com.

[5] “He Hasn’t Been Home Since,” Photoplay, August, 1919, 61, Internetarchive.org.; “The Right Bower,” circa 1920, Indiana Historical Society, David L. Smith Collection, Collection #P568, Box 1, Folder 3.

[6] “He Hasn’t Been Home Since,” Photoplay, August, 1919, 16: 3, 61, Internetarchive.org.

[7] Brady produced both plays and films. IMDB credits him for producing forty-three films from 1897-1920. Here are some examples of Brady-produced plays in which Bowers was a cast member: “At the Brady Playhouse,” Brooklyn Citizen, November 30, 1913, 17, Newspapers.com.; “The Family Cupboard” Chat [Brooklyn, New York], January 3, 1914, 16 Newspapers.com.; “Attractions of Current Week in Leading Washington Theaters: Family Cupboard,” Washington Herald [Washington, D.C.], January 18, 1914, 18, Newspapers.com.; “Belasco: The Family Cupboard,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], January 20, 1914, 8, Newspapers.com.; “This Week in the Theaters: Alvin,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, January 25, 1914, 23, Newspapers.com.; “Attractions at the Theatres: The Decent Thing to Do,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1914, 150, Newspapers.com.; “Surpasses Drury Lane,” Brooklyn Citizen, October 8, 1914, 6, Newspapers.com.; “Plenty of New Productions Listed for Future Appearance,” Variety, October, 1914, 36, 10, Internetarchive.org.

[8] David L. Smith, “John Bowers: A Tragedy That Became a Legend,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, Fall 2017, 4, Indiana Historical Society.

[9] 1920 Census, Los Angeles Assembly District 63, Los Angeles, California; Roll: T625_106; Page: 12B; Enumeration District 167, FamilySearch.org.

[10] Paul Harris, “Library of Congress: 75% of Silent Films Lost,” Variety, December 4, 2013, https://variety.com/2013/film/news/library-of-congress-only-14-of-u-s-silent-films-survive-1200915020/.

[11] “King Baggot in ‘The Baited Trapm,’” Great Falls Tribune (Montana), June 21, 1914, 8, Newspapers.com. See IMDB for information on film credits.

[12] “John Bowers,” Hollywood Walk of Fame, Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, November 22, 2019, https://www.walkoffame.com/john-bowers

[13] “Movie Facts and Fancies,” Boston Globe, July 29, 1923, 54, Newspapers.com.

[14] “John Bowers Narrowly Escaped Permanent Injury,” August 16, 1904, 4, Newspapers.com.

[15] Bull-dogging refers to the act of wrestling a steer to the ground by holding its horns and twisting its neck.; “Movie Facts and Fancies,” Boston Globe, July 29, 1923, 54, Newspapers.com.

[16] “Sophistication Lends Charm, is Actor’s Theory,” Los Angeles Times, May 1, 1927, 57, Newspapers.com.

[17] David L. Smith, “John Bowers: A Tragedy That Became a Legend,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, Fall 2017, 4, Indiana Historical Society.

[18] “The Sport of Kings – and Movie Stars,” Motion Picture Classic, September, 1923, 18:1, 18, Internetarchive.org.

[19] “The Sea-Going Actor,” Indiana Historical Society, David L. Smith Collection, Collection #P568, Box 1, Folder 3.

[20] “The Owner of the Uncas,” Motion Picture Classic, January, 1920, 20, accessed Archive.org, https://archive.org/details/motionpicturecla1920broo/page/n25

[21] “Notes from Movie Land,” Knoxville Journal and Tribune (Tennessee), August 10, 1924, 17, Newspapers.com. This article establishes that he began taking racing lessons.; “Famous Driver Adopts Novel Training Stunt,” Los Angeles Times, August 16, 1924, 11, Newspapers.com.; “Floyd Roberts Adds to Fame,” Van Nuys News (California), September 16, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com. The previous two articles establish that Bowers became involved in the professional auto racing world in 1924.; “50 Daredevils Gamble Lives Against Time in 250-Mile Speed Battle,” Los Angeles Evening Express, November 27, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com. This article reveals that Bowers did not race in the Thanksgiving Day race but rather contributed as an track official.

[22] “Planes are Hobby of Bowers,” Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1927, 46, Indiana Historical Society, David L. Smith Collection, Collection #P568, Box 1, Folder 3.

[23] “Yachts and Autos His Hobbyhorses,” Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1924, 48, Newspapers.com.

[24] “Publicity and the Film Star,” Film Reference, February 27, 2020, http://www.filmreference.com/encyclopedia/Independent-Film-Road-Movies/Publicity-and-Promotion-PUBLICITY-AND-THE-FILM-STAR.html.

[25] “California, County Birth and Death Records, 1800-1994,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9SF-P9BR-Y?cc=2001287&wc=SJ5X-JWG%3A285174601%2C285330201 : 22 August 2018), Los Angeles, Death Certificates 1936, no. 10100-12041, image 31 of 2142, California State Archives, Sacramento.

[26] The couple were cagey about announcing their marriage. The consensus at the time was they were married in 1924. Although IHB has been unable to unearth their marriage certificate, Marguerite was listed as Bowers’s wife in his death certificate. “California, County Birth and Death Records, 1800-1994,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9SF-P9BR-Y?cc=2001287&wc=SJ5X-JWG%3A285174601%2C285330201.

[27] “Hollywood’s Halls,” Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1927, 136, Newspapers.com.

[28] Solid proof of the separation of John and Marguerite may not exist. Exactly when they married and when they separated is uncertain. “Romance of Screen Pair Disrupted,” Los Angeles Times, December 19, 1930, 8, Newspapers.com.

[30] “Middle West,” Garrett Clipper, March 9, 1936, 2, Newspapers.com; “Middle West,” Garrett Clipper, July 6, 1936, 2, Newspapers.com; “Middle West,” Garrett Clipper, August 10, 1936, 3, Newspapers.com; “Middle West,” Garrett Clipper, August 17, 1936, 2, Newspapers.com.

[31] “Mrs. Ida Bowers,” Garrett Clipper, July 16, 1936, 1, Newspapers.com.

[32] “Body of Former Film Star Found,” Cushing Daily Citizen (Oklahoma), November 19, 1936, 12, Newspapers.com. After his death, a local newspaper reported that Bowers had been depressed and wanted to get back into movies. “John Bowers,” Indiana Historical Society, David L. Smith Collection, Collection #P568, Box 1, Folder 3.

[33] “How Bowers Met Death,” Hammond Times (Indiana), November 19, 1936, 4, Newspapers.com.