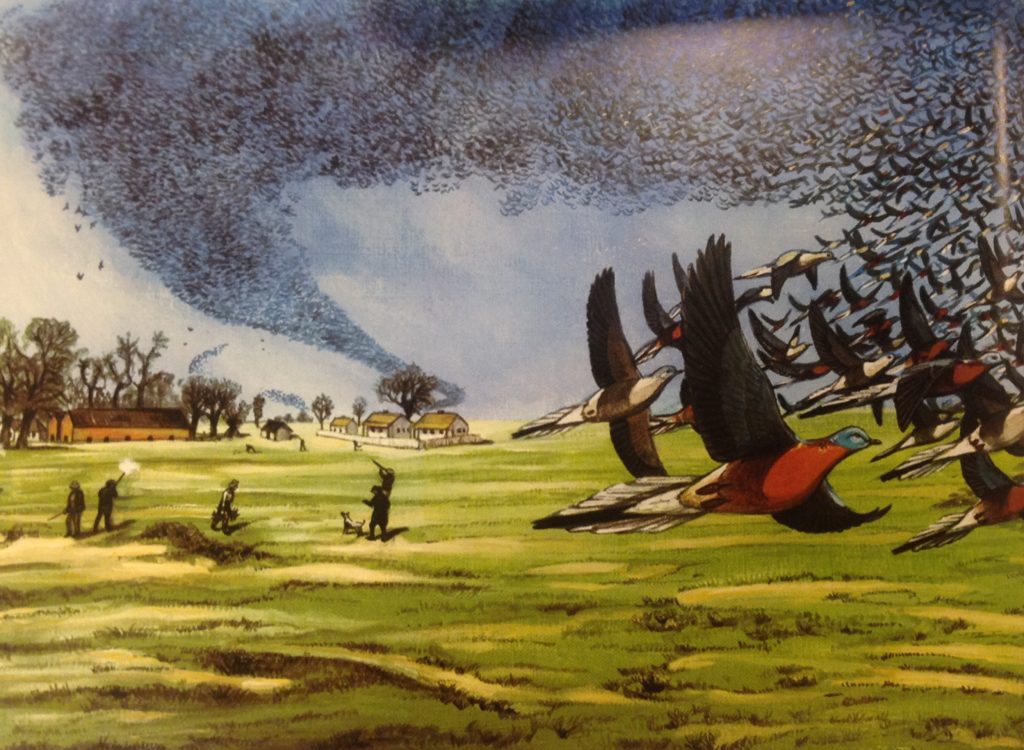

One day in rural Monroe County, Indiana during the 1870s, 10-year-old Walter Rader witnessed an astonishing natural phenomenon: passenger pigeons had gathered at his family farm “by the millions.” As the birds descended on the farm, they blocked out “almost the entire visible area of sky.” He remembered that so many pigeons roosted in the trees surrounding the farm at night “that their weight would often break large limbs from the trees.” The crash rang so loudly he could hear it clearly inside his house.

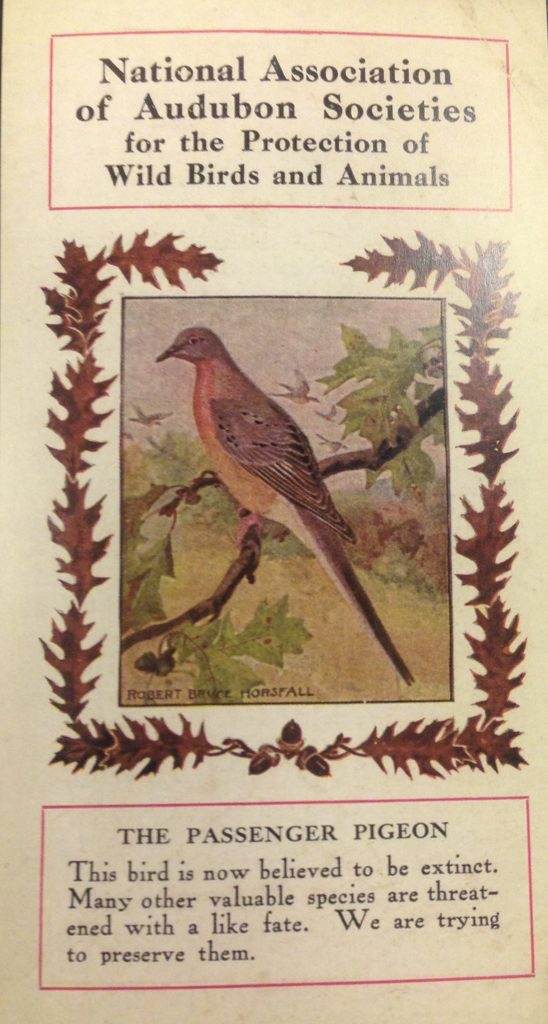

Children in the 1870s became the last generation to witness such unbelievable flights of passenger pigeons. When the Indianapolis Star shared Rader’s memories in 1934, the passenger pigeon had been extinct already for twenty years, though it had reigned as North America’s most abundant bird since the 16th century. Passenger pigeons, once so numerous that they could disrupt natural landscapes, impact the nation’s economy, and shape American social life and cuisine, became a rarity by 1900. At their disappearance, some theorized that all the pigeons had drowned in the Gulf of Mexico, flew across the Pacific to Asia, or succumbed to some mysterious disease. What happened? How could a bird so populous that it darkened the sky be reduced to none in mere decades?

The passenger pigeon had a long history of striking awe in mere humans. Its large flocks astonished early European settlers and visitors. Ralphe Humor described the wild pigeons he saw in Virginia in 1615 as

beyond number or imagination, my selfe have seene three or four hours together flockes in the aire, so thicke that even they have shadowed the skie from us.

Even early ornithologists could not believe the amounts of passenger pigeons they witnessed. John James Audubon, one of the most prominent early North American naturalists, encountered such a large flight of passenger pigeons along the Ohio River in Kentucky that he was “struck with amazement.” He recalled the “air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse, the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow.” Despite the excrement, he decided to try to count all the pigeons that flew overhead, as any dedicated ornithologist would. He pulled out a pencil and paper and made a dot on the page for every flock that passed by. Audubon gave up after about twenty minutes, as the sky overhead was still inundated with pigeons. He counted 163 dots on the page. He later calculated that he saw well over one billion pigeons that day.

According to historian Joel Greenberg, “Nothing in the human record suggests that there was ever another bird like the passenger pigeon.” Estimations indicate three to five billion passenger pigeons inhabited North America from the 1500s through the early 1800s, constituting 25-40% of the continent’s total bird population. The passenger pigeon often traveled in huge flocks and left undeniable marks on the landscapes they inhabited. They formed roosts (resting sites) and nests for breeding in trees spread across miles. Their collective weight broke branches and sometimes toppled trees. When the pigeons finally left, it sometimes looked like tornado had swept across the land.

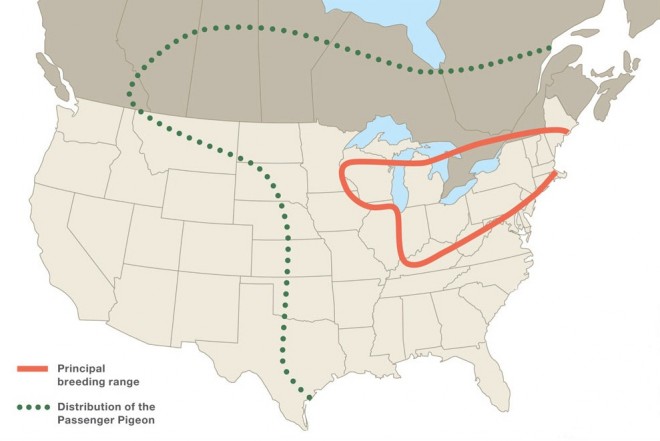

The bird only lived in North America, generally east of the Rocky Mountains, between the Hudson Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Passenger Pigeons, always on the move in their search for enough food to feed their massive flocks, generally flew north in the spring and south in the fall. Indiana falls smack dab in the middle of the passenger pigeon’s range and migration path. William Hebert wrote one of the earliest extant records of the pigeon in Indiana. In 1823, while he visited Harmony, he saw “astonishing flights of pigeons” and millions congregated in the nearby woods. Since pigeons upon pigeons inhabited each tree, no guns were even necessary to hunt them. Parties of people went into the forest at night, armed with poles, and simply knocked armloads of pigeons off the trees.

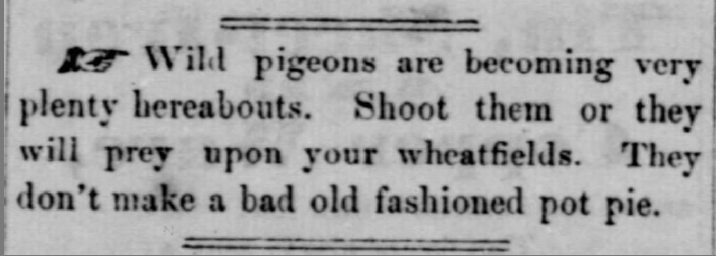

During the 18th and 19th century, Americans put their lives on hold when pigeons came to town. The bewildering sight of pigeons upon pigeons as far as the eye could see attracted amazed onlookers. The influx of pigeons became a free, relatively easy source of food that required little skill to capture or kill. Since pigeons often traveled and nested in such high concentrations, it was almost impossible to miss shooting a bird (or two) with a rifle or capture huge numbers with a net. Naturalist Bénédict Henry Révoil witnessed pigeon fever strike Hartford, Kentucky in 1847. He attested that for three days “the population never laid aside their weapons. All—men and children—had a double barreled gun or rifle in their hands,” waiting for the right moment to shoot through the thick cloud of pigeons flying above them. “In the evening the conversation of everybody turned upon pigeons . . . For three days nothing was eaten but boiled, or broiled, or stewed, or baked pigeons.”

Indiana newspapers often updated Hoosiers on the comings and goings of passenger pigeons in the state. In 1850, an enormous pigeon roost formed near Lafayette, Indiana. According to newspaper reports, four men went to the roost to hunt and returned to town with 598 pigeons. The Indiana State Sentinel encouraged others to head to the roost because “the pigeons are unusually fat and most excellent eating.” In 1854, another roost ten miles long by five miles wide near Brookville, Indiana attracted persons “coming many miles to enjoy the sport.” An Indiana Herald journalist reported that:

the roar of their wings on arriving and departing from the roost is tremendous and the flocks, during the flight, darken the heavens. The ground is covered to the depth of several inches with their manure. Thousands [of pigeons] are killed by casualties from breaking limbs of trees.

Yet, the Indiana American assured readers to come to the roost as “There are pigeons enough for all.”

This strong hunting tradition Price describes still plays out in present day Hoosier culture. For example, during the 2016 election Hoosiers voted to include an amendment that protects the right to fish and hunt, subject to state wildlife regulations, in the state constitution. Joel Schumm, a clinical law professor at Indiana University, told the Indianapolis Star this protection reflects the fact that “hunting and fishing is deeply ingrained in our culture and our state.”

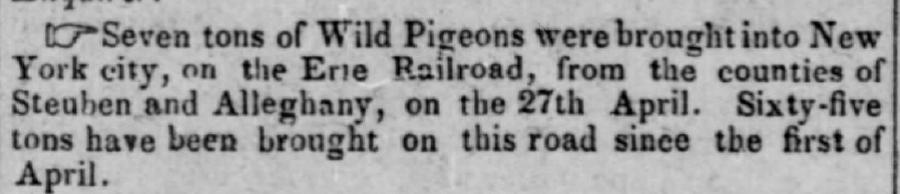

During the latter half of the 19th century, revolutionary transportation advancements put the purportedly inexhaustible pigeon population to the test. Roads, canals, and railroads connected the far corners of the country and created a national market. As the railroad expanded into rich game areas in the west, market hunters could capture or kill millions of pigeons at vast nesting sites in the North and ship them east for huge profits, instead of just selling a few at local markets.

As trains began to ship thousands of pigeons across the nation daily to supply demand, Révoil predicted that the passenger pigeon was “threatened with destruction . . . if the world endure a century longer, I will wager that the amateur of ornithology will find no pigeons except in select Museums of Natural History” in 1847. The last large flocks of pigeons appeared in the 1870s. Throughout the 1880s, ornithologists and sportsmen reported smaller and smaller flocks, until they began to worry none were left.

At the turn of the 20th century, ornithologists and naturalists called for increased wild game protection. Many sportsmen began advocating for conservation, or wise use, of natural resources and tried to overturn the widespread assumption that America’s natural resources were unlimited. Sportsmen worried that without intervention, hunting as a leisure activity would disappear because no game would be left. In 1900, Congress signed the Lacey Act into law. Championed by sportsmen and naturalists alike, the law protected the preservation of wild birds by making it a federal crime to hunt game with the intent of selling it in another state.

However, it was too late for the passenger pigeon. During the 1910s, some ornithologists offered cash rewards to the individual that could bring them to a flock or nest of passenger pigeons, as a last ditch effort to save the species. All rewards went unfulfilled, since no passenger pigeons could be found. Historian Joel Greenberg recently found new evidence, further examined in his book A Feathered River Across the Sky, that the last verified passenger pigeon in the wild was shot here in Indiana, near Laurel on April 3, 1902. A young boy shot the bird and brought it to local taxidermist Charles K. Muchmore, who recognized it at once, and preserved it until ornithologist Amos Butler verified it was indeed a passenger pigeon. Unfortunately, a leaky roof destroyed the specimen around 1915. No more substantial evidence appeared in front of Butler, or any other ornithologist for that matter, of the passenger pigeon’s existence. Butler concluded in 1912 “The Passenger Pigeon is probably now extinct,” in the wild. The last captive passenger pigeon, Martha, died in the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914, marking the official extinction of the species.

According to Iowa Representative John F. Lacey, creator of the Lacey Act, the extinction of the passenger pigeon spurred necessary support from the public, often from hunters and sportsmen, for broader wildlife protection. Though the passenger pigeon could not be saved, other animals in danger of a similar fate, like the American bison, the egret, and the trumpeter swan, survive to this day.

On April 3, 2017, 115 years after the last verified wild passenger pigeon was shot in Indiana, the Indiana Historical Bureau will unveil a state historic marker dedicated to passenger pigeon extinction. It will be located in Metamora, Indiana, five miles from where the last passenger pigeon was shot.

Check back on our Facebook page and website for more details on the marker dedication ceremony, open to the public.