Perhaps one of the most heroic soldiers of World War I, Samuel Woodfill is largely forgotten today. He would have preferred it that way. Modest and a skilled marksman, Woodfill was born in Jefferson County, near Madison, in January 1883. Growing up, he watched his father and older brothers use guns to hunt, observing how they shot. By the age of ten, he was secretly taking a gun out to hunt squirrels and telling his mother the squirrels were from a neighbor. When he was caught, his veteran father (John Woodfill served in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War), was so impressed with Woodfill’s marksmanship he was allowed to take the gun whenever he pleased.

At 15, Woodfill tried to enlist during the Spanish-American War. He was turned down, but enlisted in 1901 at the age of 18. He served in the Philippines until 1904, and returned home for only a few months before he volunteered to be stationed at Fort Egbert in Alaska. It was in Alaska that Woodfill worked on his marksmanship, hunting caribou, moose, and brown bears in the snowy landscape of the Last Frontier until 1912. Upon his return to Fort Thomas, Kentucky, Woodfill was promoted to sergeant due to his impeccable record. In 1914, he was sent to defend the Mexican border until his return to Fort Thomas in 1917. While Woodfill showed great discipline and marksmanship as a soldier, World War I would prove how exceptional he really was.

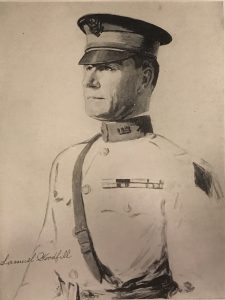

In April 1917, Woodfill was promoted to Second Lieutenant and he prepared to go to Europe to fight on the front. Before leaving, he married his longtime sweetheart, Lorena “Blossom” Wiltshire, of Covington, Kentucky. Woodfill was part of the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.), Company M, 60th Infantry, 5th Division and was promoted to First Lieutenant while in Europe.

Woodfill’s most defining moment, and one that brought him international fame, occurred on October 12, 1918 near Cunel, France during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Leading his men through enemy territory, Woodfill’s company was attacked by German soldiers. Not wanting to put any of his men in danger, Woodfill proceeded ahead alone to face the enemy. Using his marksman skills, he identified the probable locations for German nests, and took out several snipers and their replacements. As he moved forward, his men managed to keep up with him and together they braced themselves for the shelling that would continue throughout the afternoon. When it finally stopped, Woodfill went back to retrieve the pack he had left behind, discovering that the jar of strawberry jam he had been saving was gone. Hearing Woodfill grumble about the “yellow-bellied son of a sea cook” who stole it, the company cook gave Woodfill a fresh apple pie. Remembering the pie years later, Woodfill said “I don’t think any medal I ever got pleased me half as much as that apple pie.” Woodfill spent ten weeks in the hospital, recovering from the mustard gas he breathed in while taking out the German snipers.

Woodfill received the Medal of Honor for his actions in January 1919 before returning home to Kentucky. Several other medals followed, including the Croix de Guerre with palm (France, 1919), and the Croce di Guerra (Italy, 1921).

He left the Army in November 1919, but quickly realized that after such a long time in the forces, finding a job would be difficult. Three weeks later, he reenlisted as a sergeant, losing his rank of captain he had achieved during the war. But as long as Woodfill was in the Army and living a quiet life, he was happy. Soon, his heroic actions during the war were forgotten by the public. This changed in 1921 when Woodfill was chosen to be a pallbearer to the Unknown Soldier by General Pershing. Upon seeing Woodfill’s name on the list to choose from, he exclaimed,

“Why, I have already picked that man as the greatest single hero in the American forces.”

Interest in Woodfill and his story gained popularity, and the fact that he had lost his rank as captain bothered many. Appeals as to his rank would appear in the Senate, but proved fruitless. Woodfill’s rank did not bother him, but the pay did. He wanted to provide for anything his wife wanted, and could not do that on a sergeant’s pay. In 1922, he took a three months’ leave from the Army and worked as a carpenter on a dam in Silver Grove to make enough money to pay the mortgage. By 1923, Woodfill was able to retire from the Army with a pension. Author Lowell Thomas took an interest in Woodfill and published a biography titled Woodfill of the Regulars in 1929 in an attempt to help Woodfill pay his mortgage. Framed as Woodfill telling the story of his life, Thomas had to add an epilogue to include the prestigious honors he received because Woodfill only included the Medal of Honor.

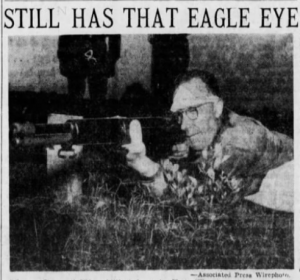

In 1942, the War Department reenlisted Woodfill and Sergeant Alvin York, another WWI hero. Having lost his wife a few months earlier, Woodfill sold everything he owned and went off to serve in WWII. Woodfill passed most of the entrance exams, but had to be given special clearance because he did not have the minimum number of teeth required to serve. (Check back to learn about Hoosier dentist Dr. Otto U. King, who, through the National Council of Defense, mobilized dentists to treat military recruits rejected due to dental issues during World War I). At 59 years old, Woodfill was still an excellent marksman, hitting “bull’s-eye after bull’s-eye” on a rifle range in Fort Benning, Georgia. He did not serve long, as he hit the mandatory retirement age of 60 in 1943.

Rather than returning to Kentucky, Woodfill settled in an apartment in Vevay, Indiana. He spent his remaining years in solitude, enjoying the anonymity that he had craved throughout his career. He died on August 10, 1951 and was buried in a cemetery between Madison and Vevay. In 1955, Woodfill’s story resurfaced and a push to honor the WWI hero resulted in Woodfill’s body moving to Arlington National Cemetery. He was buried near General Pershing with full military honors in October 1955.

Woodfill did not enjoy the spotlight, but after taking on the enemy singlehandedly in the midst of a battle, he deserved it. He worked hard throughout his life with little expectation of recognition for his great accomplishments.