In the summer of 1881, typhoid fever swept through small town Bluffton, Indiana. Sixteen-year-old Charles C. Deam was one of the many Wells County residents who caught the disease. In the time before antibiotics, basic medical practice offered few treatments, especially in rural America where trained doctors were scarce. According to Deam’s biographer, Robert Kriebel, Deam survived after drinking an old pioneer remedy: milk boiled with an herb called Old-Field Balsam. This incident marked the first chapter in Deam’s dedication to studying and promoting Indiana’s plant life as a botanist, first state forester, and author.

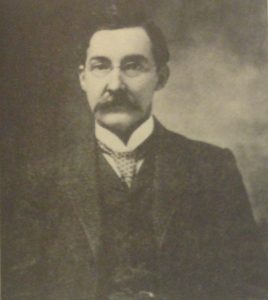

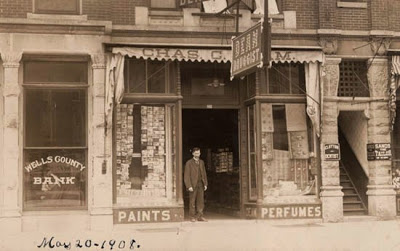

Charles Deam was born on August 30, 1865 in Bluffton, Indiana. He grew up on a typical pioneer farm, attended country school and later, the town’s new high school. He completed several consecutive stints teaching public school, attending DePauw University, and working as a farm laborer before deciding to enter the drugstore business in 1888. After an apprenticeship in Marion, Indiana, and a brief assignment as a druggist in Kokomo, Deam returned to Bluffton to run a drugstore in 1891.

Each job required long hours. At Kokomo, he worked a tiring 84 hours per week to keep the store open from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. Monday through Saturday. To deal with the stress, a doctor advised Deam to get out of the drugstore and take a walk through the countryside each day. However, Deam’s incredible work ethic refused to let him simply take leisurely strolls. Instead, Deam and his wife, Stella drew on their passion for collecting things, such as stamps, rocks, or coins, and picked samples of plants and flowers they found on their walks.

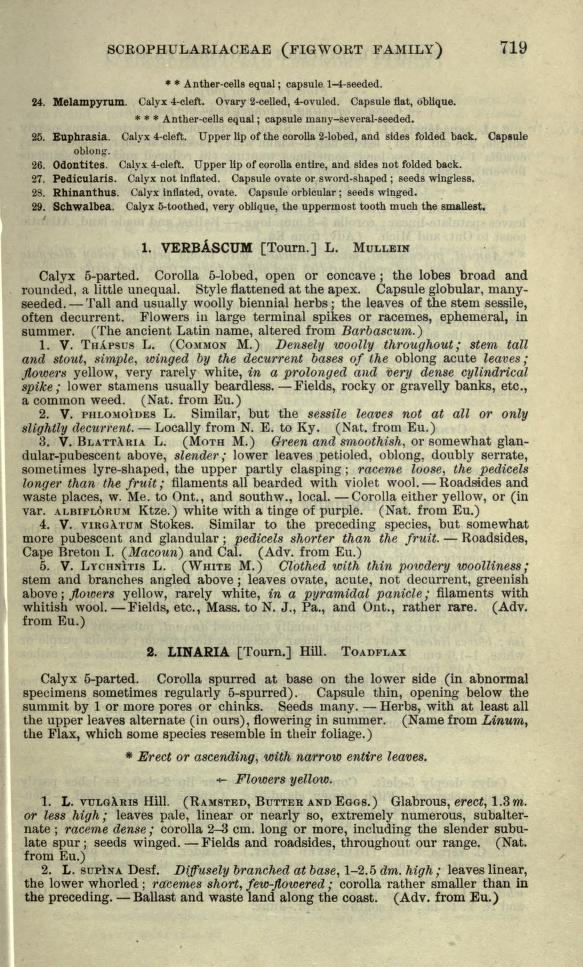

Deam’s curiosity about the various plants he encountered grew. Luckily, he met Bruce Williamson, a zoology student at Ohio State University, in 1896. One day, Deam and Stella discovered an unusual looking plant and brought it to Bruce to identify. Bruce simply handed over a copy of Gray’s Manual of Botany so they could figure it out themselves. Deam enjoyed going through the book’s key to uncover the plant’s identity; a moth mullein, Verbascum blattaria.

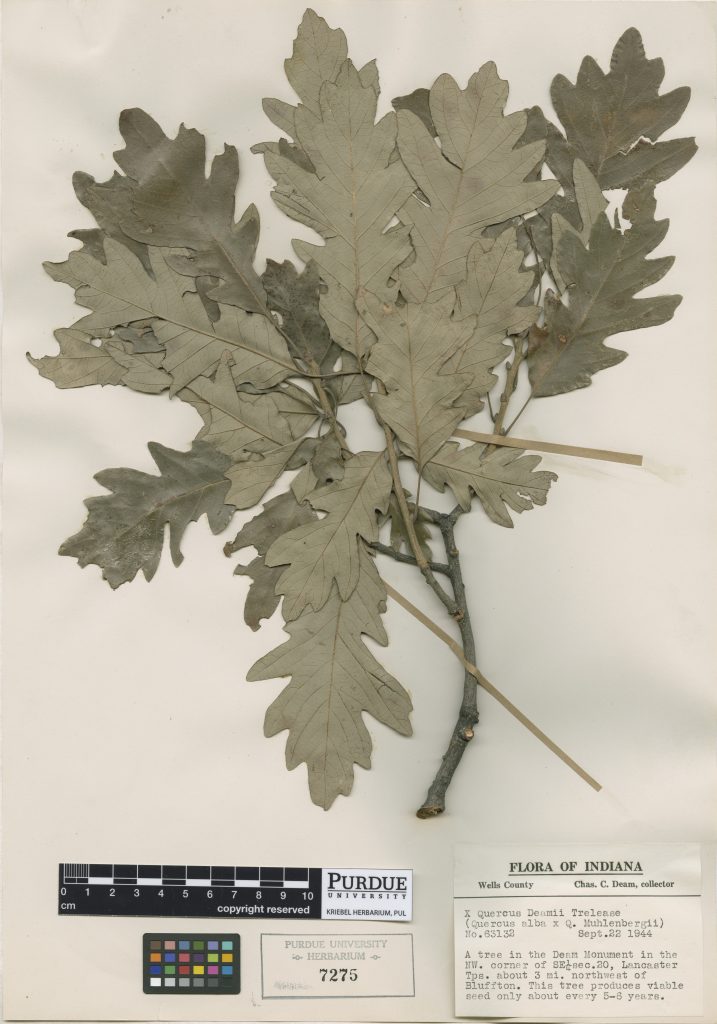

From then on, Deam was hooked. Bruce taught Deam botany basics: how to take field notes, the proper methods to collect specimens, and which books to use to help identify plants. Deam mounted his first specimen on September 13, 1896, a snapdragon called Ilysanthes dubia. Deam, ever the perfectionist, mounted it according to botany standards, on 11.5 by 16.6 inch paper. Eventually Deam collected more than 73,000 specimens, each meticulously catalogued this way. He even collected specimens from every one of Indiana’s 1,008 townships.

Don’t be fooled, though. For Deam, botany was more than a quest to grow a large collection of rare specimens. Robert Kriebel described Deam’s passion for botany as a vehicle to “detect subtle changes in nature, the spreading of some plants, and the disappearance of others. These ongoing changes were baffling, exciting, and unexplored.”

In his early years as a fledgling botanist, Deam spent his Sundays biking to neighboring Indiana counties to find more specimens to study. He and Stella also took collecting trips to Florida, Guatemala, and Mexico. On these trips, the two often found a few rare or previously unidentified plants. He sent specimens to notable, professional botanists at Harvard, University of Michigan, Purdue University, Indiana University and other institutions, who later named them for the first time and shared Deam’s discoveries with the broader scientific community. Botanists saw the value of Deam’s carefully mounted specimens. Deam carefully chose the specimen that most accurately represented its species, and noted the date, place of collection, and description of the surrounding habitat and environment. These connections helped Deam evolve from an amateur botanist into a nationally-known professional.

Around 1905, Deam began to realize that the most successful botanists focused on a specific area of the field and limited their work to a certain geographic area. He decided to focus on Indiana plants only, and gave away hundreds of specimens he collected outside the state to herbariums housed in universities, museums, and other institutions around the country. This new statewide focus allowed Deam to publish his findings in the Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science and he slowly became somewhat of a star in the scientific community in the state.

As Deam’s renown spread, Governor Thomas Marshall asked Deam to act as the first full-time Indiana state forester in 1909. The job would require him to live in Indianapolis for part of the year and spend the other part supervising the newly created Clark State Forest near Henryville, Indiana. At first, Deam denied the appointment. Between his drugstore business and his collecting trips in the field, he felt he had no time to spare. However, after much persuasion from colleagues, as well friends and neighbors in Bluffton who had lobbied hard to secure Deam the appointment, Deam realized that he would wield tremendous influence as the state forester over botany, as well as forestry in Indiana. The position permitted state-paid travel and further opportunities to botanize on weekends. Furthermore, the ability to flash a state badge (in dire situations only, of course) would allow him entrance to lands that before had been restricted.

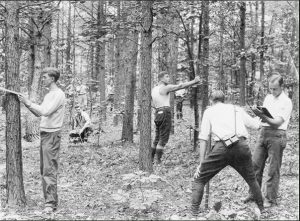

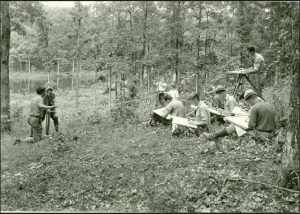

Deam worked as state forester from 1909-1913 and 1917-1928. Under Deam’s supervision, a period of outstanding forestry education and research began in Indiana. He kept detailed, official records of the state’s important experimental tracts at Clark State Forest. These experimental tracts were part of Indiana’s attempts to reforest the state. Indiana’s first settlers had long ago cleared much of the state’s widespread, dense hardwood forests for farming, fuel, and lumber. The experimental tracts, which tested methods of planting, pruning, and reforestation, would help determine which tree species were best suited to Indiana’s soil, topography, and climate.

Through these experiments, Deam debunked the myth that original species of trees, in Indiana’s case, hardwoods, grew best if replanted in the same soil. Deam applied the practice of agricultural crop rotation and discovered that conifers actually thrived on land that once held hardwoods. Thereafter, planting pine trees became common in reforestation projects in Southern Indiana.

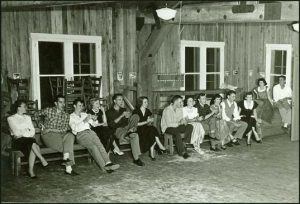

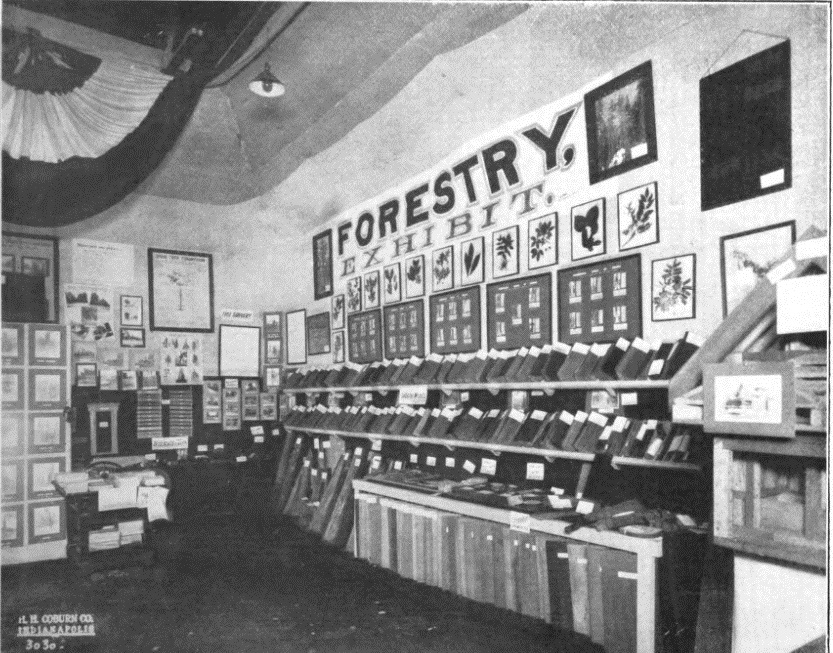

In addition to guiding this reforestation process, Deam worked hard to educate Hoosiers about the value of forestry in the state for both economic and environmental purposes. Deam held an annual forestry essay contest for students, created a forestry exhibit for the Indiana State Fair, issued educational press releases, and held special visitor days at Clark State Forest to show off the work being done.

In 1921, Deam wrote and lobbied for the passage of the Forest Classification Act, which established methods to keep the state’s private forests intact. The law created standards that landowners maintain in order to exempt their woods from taxation. The program, perhaps Deam’s most important legacy in Indiana forestry, currently includes 410,000 acres of forested land. After passage, other states created similar laws modeled after this one.

By 1928, Deam decided to leave forestry behind to pursue his true passion, plant taxonomy and writing. The state of Indiana didn’t seem to want to give Deam up, though. Since a “state botanist” position didn’t exist, the state made Deam a “research forester,” so he could be paid to continue his work cataloging the natural history of Indiana.

His first book Trees of Indiana, signifies the first phase of this process. Published in 1912, it became the most comprehensive book of its type published in the state. As a drug store owner, Deam had long been writing Deam’s Almanac for his customers, chock-full of wit, flashy advertisements, weather reports, and sensational cures for various ailments. This experience writing for popular audiences expanded the readership of Trees of Indiana beyond scientists. While the book included biological keys for identification, tables, charts, and scientific data for serious scholars, it also contained anecdotes, sermons, and Deam’s own personal commentary.

The resulting familiar style made the book’s appeal extend to students, teachers, and hobbyists, in addition to professional botanists and foresters. Indiana printed 10,000 free copies, which were exhausted within three years. Thousands of requests for additional copies could not be filled until 1919, when additional funds allowed for a reprinting. These 1,000 copies were all given away within 5 days. Over the next four decades the book was reprinted and revised, and often used as a key text for forestry students in universities around the nation.

The popularity of Trees of Indiana launched Deam’s fame within the state and nation. He wrote three other similar books, Shrubs of Indiana (1924), Grasses of Indiana (1929), and Flora of Indiana (1940) in order to help record Indiana’s natural surroundings before advancing agriculture, industry, and urbanization destroyed it.

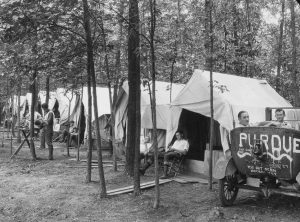

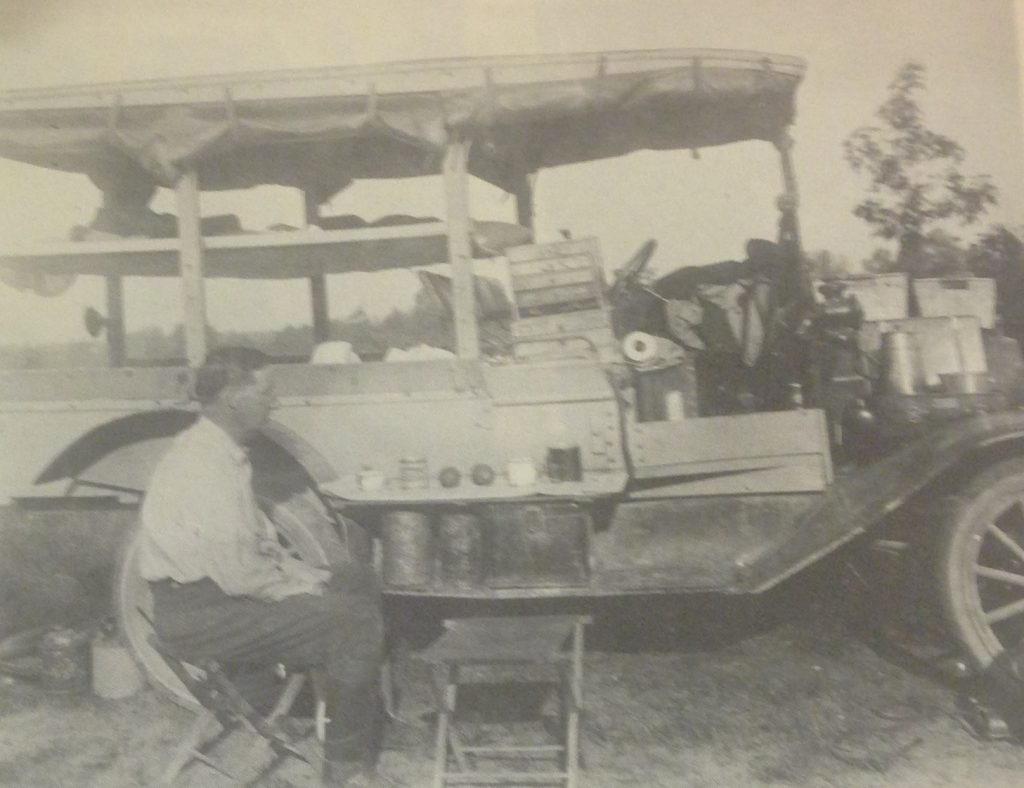

Somehow, Deam still found time to get out in the field and botanize. In 1915, he bought a Ford Model T and equipped it specially to supplement his collecting practice. He fitted a truck type body he bought from a Bluffton wagon-maker to the car. He also attached canvas flaps, drawers, shelves, and storage cubicles to it to house all his tools, materials, and collected specimens. He even included enough sleeping space for him and Stella, as well as a hammock if another of his colleagues joined them. This vehicle, christened the “weed wagon,” carried him to every Indiana township. The weed wagon, much speedier than travel by horse, bike or on foot, helped Deam dramatically increase his collection. Before acquiring the vehicle, he averaged an addition of 1,500 specimens per year; in 1915 he added 3,764 specimens.

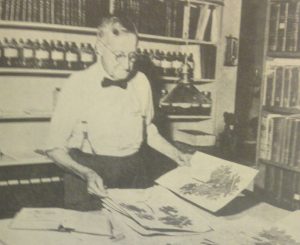

After Deam finished Flora of Indiana in 1940, he began to slow down, but not by choice. He suffered from arthritis, poor eyesight, loss of hearing, and gout. He still collected, but at a much slower pace. Still, by the time of his death in 1953, he had collected more than 70,000 specimens, all contained in his in-house herbarium at his home in Bluffton. In 1931, he arranged to have his entire collection sold to Indiana University at Bloomington at the price of $10 per 100 sheets. Botany students can still peruse his collection housed in the Smith Research Center on the Bloomington campus.*

Today, Deam’s legacy lives on. He currently has a tree, a lake, a national wilderness area, and 48 small plants named after him. Numerous universities, including Wabash College, DePauw University, Indiana University, and Purdue University awarded him numerous honorary degrees and distinctions throughout his life. Even though Deam wrote modestly in 1946, “I am just plain Charley Deam and I never want anyone to think anything else,” he clearly helped Hoosiers realize the importance of their forests and flora, and ensured it would be studied for generations to come.

*For information about how to use the data portals please see this guide and Zoom presentation.