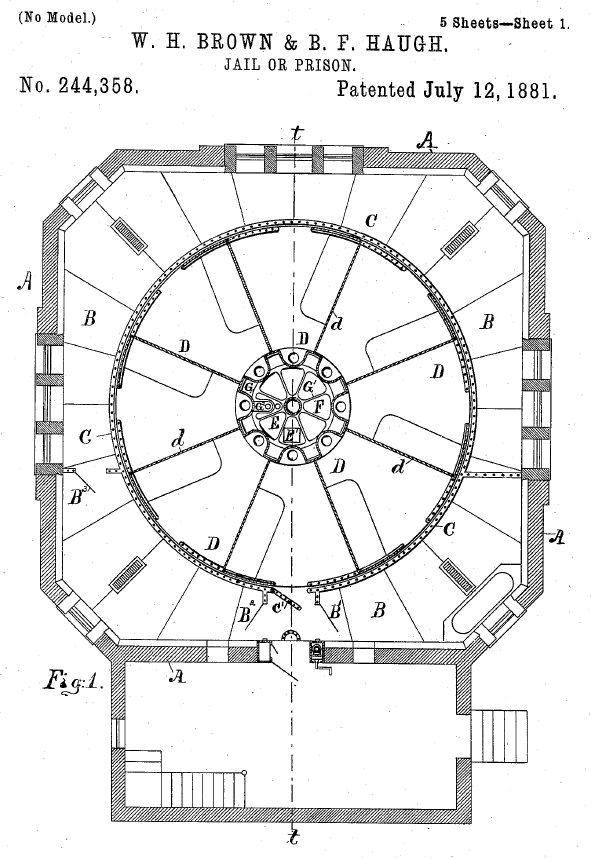

One of the nineteenth century’s most idiosyncratic inventions was the rotary jail. Inspired by the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham, rotary jails were circular enclosures that allowed guards a 360 degree view of inmates through moving cells via a crank. There was only one access point, making escape more difficult. This type of jail was invented in Indiana by architect William H. Brown and iron industrialist Benjamin F. Haugh. These Indianapolis-based inventors filed their patent patent in 1881.The design became popular, largely because it decreased interaction between guard and prisoner. In fact, the prisoner did not even have to be removed from his cell to dispose of waste. In this blog post, we’ll expand our knowledge of these jails through more newspaper accounts from throughout the United States.

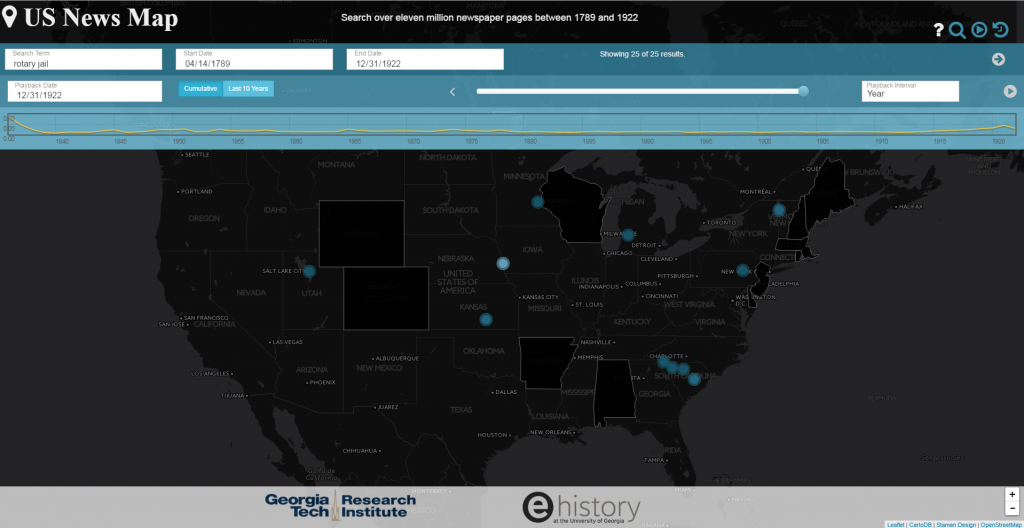

But how do we start? One great tool for looking for subjects and their relevance to newspapers is usnewsmap.com. A joint venture of the Georgia Tech Research Institute and the University of Georgia, US News Map provides visitors with an easy search tool that show where subjects show up on the map. When I typed in “rotary jail,” I got eleven hits; some were as far east as Vermont and as far west as Utah.

In Burlington, Vermont, a rotary jail was built as early as the late 1880s, with city planners waxing enthusiastic about the invention after their visit to the flagship rotary jail in Crawfordsville, Indiana. “They were most favorably impressed with the new rotary jail at Crawfordsville, Ind., and the probability is that they will decide to erect a similar one in this city,” wrote the Burlington Free Press on March 25, 1887. In Picturesque Burlington, a short history written in 1893 by Joseph Auld, describes the rotary jail in detail:

This “cage” is closely surrounded by a barred iron railing with only one opening. When a prisoner is to be placed in his cell the “cage” is revolved till the proper cell fronts the door; then the prisoner is put in, the cage is turned, and he is secure. The number of prisoners is small and the offences venial, largely violations of the prohibitory law.

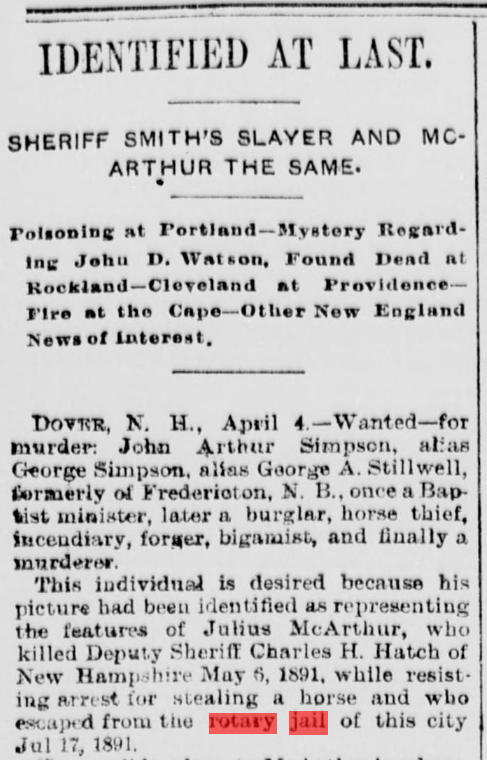

Despite the reputation that rotary jails were nearly impossible to break through, escapes occurred periodically throughout the country.

For example, one particular story from the Burlington Free Press comes to mind. As reported on April 7, 1892, a man named John Arthur Simpson, whose aliases included “George Simpson” and “George A. Stillwell,” was accused of murder in Dover, New Hampshire. Simpson, whose past lives included “Baptist minister, later a burglar, horse thief, incendiary, farmer, bigamist, and finally a murderer,” apparently bared a remarkable resemblance to Julius McArthur, who “killed Deputy Sherriff Charles H. Hatch of New Hampshire May 6, 1891 while resisting arrest for stealing a horse and who escaped from the rotary jail of this city Jul 17, 1891.” According to the newspaper report, Simpson likely escaped from jail using a knife “as a wedge to open the cell door” and the authorities searched for a supposed accomplice who gave him said knife. Even though rotary jails garnered a reputation for being tough to escape, Simpson’s story shows they weren’t completely impenetrable.

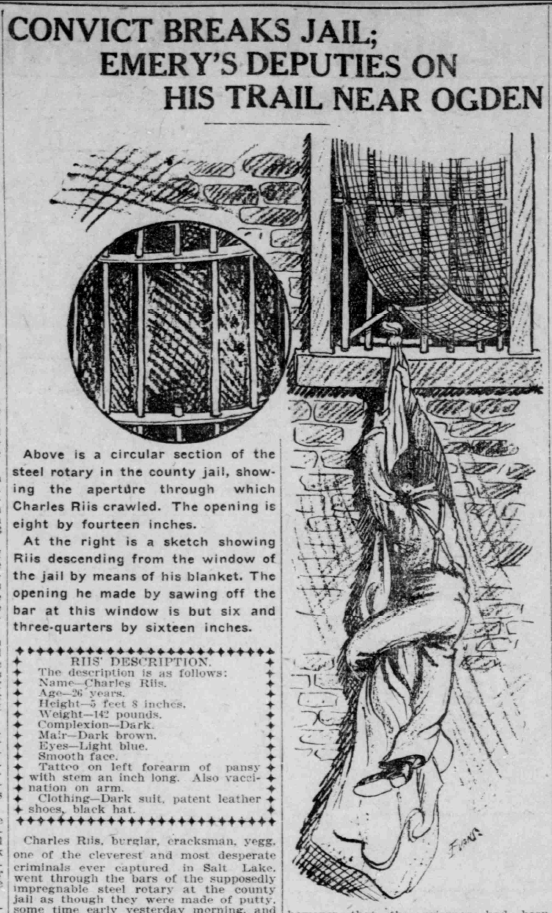

Another rotary jailbreak occurred in Salt Lake City, Utah. Charles Riis, convicted of larceny under the name “Charles Merritt,” reportedly “went through the bars of the supposedly impregnable steel rotary at the county jail as though they were made of putty,” wrote the Salt Lake Herald on February 2, 1907. Riis was said to have “crawled” through a cell “eight inches wide by fourteen inches and length” after sawing through a bar over a few days, slowly as to not alert the sheriff. He then used the sawed bar as leverage to scale down the side of the jail wall with a blanket. At the time of this article, his whereabouts were unknown. Riis’s clever maneuvering utilized the weaknesses of both the rotary jail as an invention and the law enforcement agency’s inability to anticipate his covert actions.

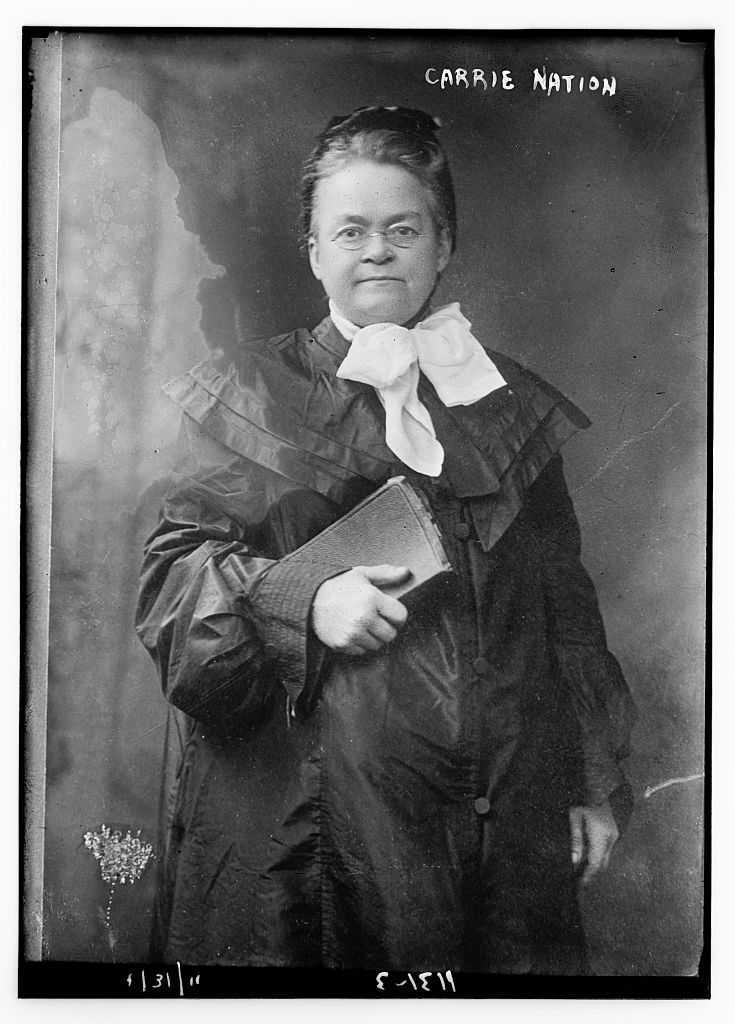

However, these stories pale in comparison to what was reported in multiple newspapers in Kansas. Carrie Nation, noted prohibitionist and provocateur, instigated a spat with the Wichita Sheriff’s wife and placed in a rotary jail cell in 1901. From here, we get two different sides of the story. According to the May 3 1901 issue of the Kinsley Graphic, Nation was “placed in the rotary cell at the county jail. She abused the sheriff’s wife, calling her all kind of vile names, the ‘devil’s dam being one.” She also called another woman “two-faced” as she was sitting in the rotary cell. However, the Topeka State Journal quoted Nation directly, painting a contrasting narrative. Nation, quoted in the Journal, wrote:

I was put in this [rotary] cell because I told Mrs. Simmons, the jailor’s wife, that when I was here before she tried to have me adjudged insane. She said I was a woman who used low, obscene language to her husband. I told her she lied and all liars would go to burn in the lake of fire. Her husband told me this morning when he came to remove me that his wife wanted me to be put here. Poor, depraved wretch! What a shame to see a cruel, revengeful woman. John the Baptist lost his head from just such a one. I would rather die in this unwholesome place than be such. I wish she would let Jesus change the bitter to the sweet in her nature. What a miserable woman she is! My poor sisters in this Bastille are trusting in the Lord.

She then railed against the liquor trade in Wichita, advising all citizens to “avoid getting anything from this cursed Sodom,” and comparing her treatment in the rotary jail to the “cruelty and injustice” of the “Spanish inquisition.” Nation’s brush with rotary jails is one of many legendary stories of the gilded age crusader.

Finally, rotary jails not only dealt with prisoners getting out, but also unintentionally trapped in. The November 10, 1886 issue of the Fairfield News and Herald, out of Winnsboro, South Carolina, reported that the rotary jail in Council Bluffs, Iowa “became locked Monday morning by some disarrangement of the machinery, and no prisoners could be taken out nor any admitted.” The paper further noted that a “large force of men were at work all day on the machinery, but the trouble was not removed until Tuesday morning.” This story was also picked by the Laurens Advertiser, the Manning Times, and the Pickens Sentinel.

Between the escapes and the structural failures, you would think that rotary jails would have lost sway with the law enforcement community and the general public. As the previous post mentioned, efforts to stop the use of rotary jails began as early as 1917. By the mid-20th century, many rotary jails were discontinued or the cell blocks were immobilized. Two former rotary jails served as county jails well into the 20th century, with the Council Bluffs jail closing in 1969 and the Crawfordsville jail in 1973.

Although the rotary jail is no longer used, the seminal Indiana invention left a profound mark on the history of crime and punishment in the United States. Its design really broke the mold, or as you could say, broke (out of) the cell.