On July 18, 1862, a brash young Kentuckian with aspirations of military advancement, Adam R. “Stovepipe” Johnson, used a rowboat and a small flatboat ferry to lead a group of approximately thirty men across the Ohio River from Kentucky to Newburgh, Indiana. Landing on the waterfront, unoccupied at lunch time, Johnson and his men seized a small store of weapons from a riverside warehouse and bluffed a group of some eighty Union soldiers convalescing in a nearby hotel into surrendering their unloaded muskets. Johnson’s men then looted a few homes and stores, paroled their prisoners, and returned safely across the river with their booty. The entire action lasted only a few hours.

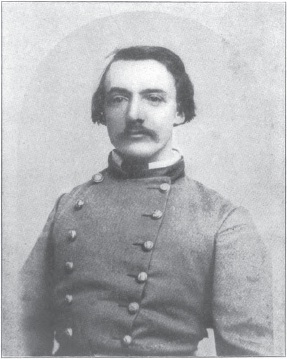

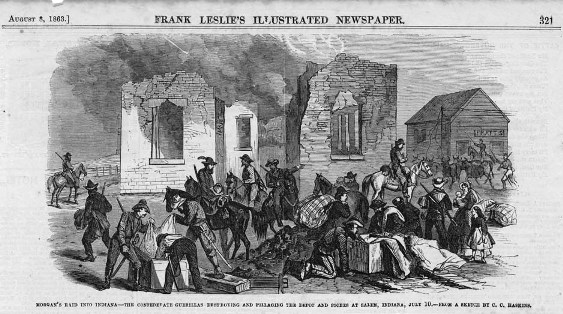

Johnson recounted the events many times, and eventually published the account in his memoir, Partisan Rangers of the Confederacy. Filled with enthusiasm, southern chivalry, and name-dropping—although often sparse on corroboration—his memoir placed the Newburgh raid in the context of Confederate movements in Kentucky in the summer of 1862. If it had no other effect, the Newburgh affair enabled Johnson to raise and arm a number of youthful recruits for what became his 10th Kentucky cavalry (CSA). He returned to Indiana a year later as a brigade commander in General John Hunt Morgan’s 1863 raid.

Johnson’s actions provide an opportunity to consider the role of southern fighters in the Ohio Valley. Using the language of the 1862 Confederate Partisan Ranger Act, he pictured himself in his later book as part of a military force operating in an irregular manner under the authority of such superiors as General Nathan Bedford Forrest and General John C. Breckenridge. Yet at the time of the raid, his own account suggests he had no formal appointment as an officer, wore no uniform, and commanded a hastily assembled body of civilians—more guerrillas than soldiers. Union authorities certainly viewed him as little or nothing more than a brigand, and rejected the authority of the paroles he had issued to his eighty prisoners.

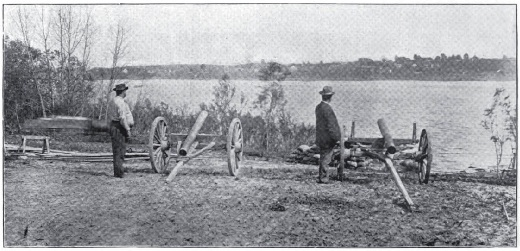

The Newburgh raid may have had greater influence upon Union war activities in Indiana and the Ohio Valley than any results that Johnson claimed for his cause. The total surprise and the bloodless success was, without doubt, a shock to many Hoosier leaders. In Newburgh, it embarrassed the local Indiana Legion commander, a merchant with an unusual first name, Union Bethell. He had been among those lunching while the raiders struck, and had previously enjoyed limited success in raising and training a local company of that state militia. Accordingly, he had stored the weapons provided for them in his own unguarded riverfront warehouse. When Bethell arrived on the scene in civilian attire, he refrained from more than verbal protests after Johnson pointed out two cannon emplaced across the river—cannon that were actually dummies made from a blackened log and the piece of stovepipe that gave Johnson his subsequent nickname.

Through chance rather than Confederate action, the telegraph line from Newburgh to Evansville was not in operation. Word of Johnson’s incursion thus took extra hours to reach state and federal military authorities. When it did become known, the raid set in motion several frantic days of Union responses. Lieutenant Colonel John Watson Foster, on leave from the 25th Indiana Regiment, took command in Evansville. He called for volunteers, including local convalescent Union soldiers, assembled a small riverboat flotilla, sailed up the Ohio River to the mouth of the Green River—where Johnson’s raiders had taken their loot—and engaged in skirmishing with a small number of Confederate guerrillas.

Finding few defenders, Foster then proceeded to Newburgh. Half a dozen local residents who were perceived as friendly to the rebels were arrested. One, Andrew Huston, was later tried and acquitted by a federal court jury in Indianapolis on changes of treason and assisting the rebels. Two other Newburgh residents who had assisted the raiders were slain by members of an angry local crowd before order was restored.

As often happened in military emergencies, Governor Oliver P. Morton soon took a visible hand. First in Indianapolis and then in Evansville, he issued repeated calls for volunteers, and urged vigorous military responses. Within three days, state and federal military officers had sent approximately a thousand regulars and volunteers to the scene, occupied Henderson, Kentucky, and sent probes into that city’s countryside. One of the probes, led by Captain Bethell, recovered a portion of the stolen arms—as well as his local reputation—at a nearby farm.

The occupation of Henderson proved to be a long term consequence of the raid; Newburgh would not again be threatened. Occurring during a call for large numbers of new volunteers, the raid also proved to be a significant boost for Union recruiting in Indiana. The July volunteers were formed into a short-lived thirty day unit, the 76th Indiana. Volunteers of longer service would become parts of the 65thand 78th Indiana regiments. Several thousand more Indiana volunteers joined the Army in the following days and weeks. Disappointed with the performance of his militia, Morton returned to Indianapolis and devoted much time to improving militia equipment and training, and extending the telegraph network along the exposed Ohio River.

Bibliography:

Mulesky, Raymond, Jr., Thunder from a Clear Sky: Stovepipe Johnson’s Confederate Raid on Newburgh, Indiana. (Lincoln, Neb.: iUniverse Star, 2006).

Davis, William J., ed., The Partisan Rangers of the Confederate States Army: Memoirs of General Adam R. Johnson. (Austin, Tex.: State House Press, 1995). Reprint of the original edition published by Geo. G. Fetter Company, Louisville, 1904.

Terrell, W. H. H., Indiana in the War of the Rebellion: Report of the Adjutant General. (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1960). Reprint of volume one of the eight-volume original report, 1869. See especially pages 181 to 189.