Historians often refer to the Suffrage Movement. However, an examination of its leaders shows many movements with sometimes conflicting goals and methods. Evaluating the campaign for the Indiana General Federation of Women’s Clubs presidency in 1915 illustrates this and provides a glimpse into the everyday happenings of suffrage at the local and state levels, including slandering efforts that reflect our modern-day politics.

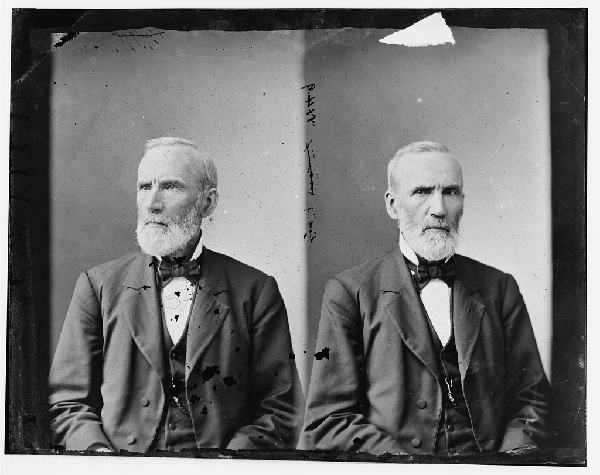

Grace Julian Clarke is most notably remembered for her local advocacy as a clubwoman, journalist, and staunch supporter of women’s suffrage. Living and working primarily in Irvington, Indiana—annexed by Indianapolis in 1902—she attended Indianapolis Public Schools and graduated from Butler University (located in Irvington at the time). She earned her B.A. in 1884 and her M.A. in 1885 in philosophy. She was the daughter of George W. Julian and granddaughter of Joshua Reed Giddings, both of whom were leading abolitionists and members of the United States Congress. Laura Giddings, Clarke’s mother and the daughter of Joshua Reed Giddings, exposed Clarke to women’s organizations when she, and others, organized the Indianapolis Woman’s Club in 1875.

Furthering familial ties to political and legal activists, Clarke married attorney Charles B. Clarke on September 11, 1887. In addition to practicing law, Charles Clarke also served in the Indiana Senate in 1913 and 1915. Prior to their marriage, Charles had worked closely with George W. Julian as a U.S. Deputy Surveyor in the New Mexico Territory. Grace was a writer for the Indianapolis Star from 1911 to 1929. She authored three publications related to her father— George W. Julian Vol. 1, Indiana Biographical series; Later Speeches on Political Questions: With Select Controversial Papers; and George W. Julian: Some Impressions. Furthermore, Clarke was a founder, president, and activist for numerous women’s clubs in Indiana between 1892 and 1929.

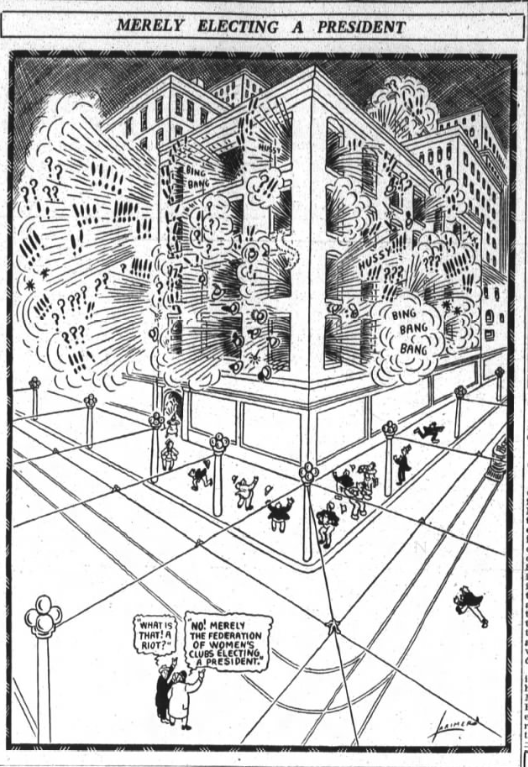

Clarke’s work, however, was not always marked by success. In 1915, Clarke declared her support for Terre Haute’s Lenore Hanna Cox in the campaign for president of the Indiana General Federation of Women’s Clubs. Cox, however, was ultimately defeated in a landslide by Carolyn Fairbank of Fort Wayne. The political conflict between Cox and Stella Stimson, with movers and shakers like Grace Julian Clarke at the forefront, demonstrates women’s political activism and ambition prior to obtaining enfranchisement. Far from bystanders of the male-dominated political sphere, women were at the foreground of their own political wars before they could legally vote.

Clarke’s, Cox’s, and Stimson’s political engagements reflect passion founded not only on morality and ethics, but also political gain. Clarke’s dedication to Cox illustrates a failed political alliance in an otherwise successful lifetime vocation. Clarke was prepared to risk her reputation to advance her political agenda. The same is true for Stimson, although Stimson engaged in manipulative politics reflective of allegations against male politicians in newspapers. Thus, evaluating the campaign demonstrates the complex layers associated with suffragists and clubwomen during the years leading up to enfranchisement. It further demonstrates how women complied with and rebelled against social normative values and beliefs.

The 1915 election gained widespread attention from clubwomen and men alike. Clarke strongly detested Cox’s most formidable opponent, Stella C. Stimson, for her participation in what Clarke viewed as unethical campaign practices. Caught in a battle of circulating letters in which personal attacks were made against Cox, Stimson stated that she would not be running for presidency. Yet even without formally running against Cox, Stimson was by far Cox’s foremost threat. Cox and her supporters suspected that Stimson was using Fairbank as a fill-in candidate to enact her own temperance agenda.

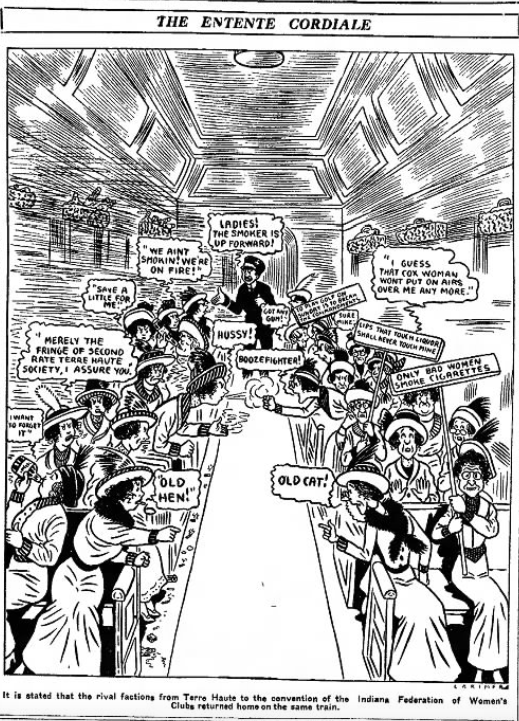

Cox and her loyal supporters did not hesitate to publicly retaliate after Stimson began circulating “scandalous rumors” including allegations that Cox was a cigarette smoker, saloon supporter, perpetual curser, and an atheist. Grace Julian Clarke spearheaded the campaign against Stimson, disputing both publicly and privately that Stimson was disloyal, as well as a liar and cheater, as shown by her deceitful assault on Cox. Clarke further criticized Stimson for engaging in what the Indianapolis Star referenced on November 9, 1915 as “machine politics” during the campaign, including allegations that she was active in having the franchise vote thrown out at the Federation convention. This contention ultimately led to formal requests for Stimson’s resignation as a Woman’s Franchise League of Indiana’s board member in the weeks after the election. Although Stimson claimed that she had not tampered with the votes, it is undeniable that she had aggressively campaigned throughout the state to guard the Federation from Cox’s leadership.

Stimson recognized the importance of recruiting Clarke, whom the The Tribune named “undefeatable.” Stimson wrote Clarke on multiple occasions pleading that she heed her personal evaluation of Cox and shift her alliance. Bound by loyalty to an ethical campaign free from dishonesties, in addition to Cox’s common views regarding suffrage, Clarke refused to be entertained or deterred by Stimson. Clarke wrote to Stimson on August 28, 1915: “I would rather be guilty of all the sins charged by you against Mrs. Cox than have to reflect that I had deliberately sought to blast the reputation of one who for years had been honored by thousands.”

The allegations against these women, and their implications, were noted within weeks of Grace declaring her support for Cox. In a letter to Clarke written on August 17, 1915, Helen C. Benbridge noted that:

this has come to be a much more important matter than just the election of one woman. It has turned into a struggle between the progressive and the reactionary elements and may mean a great deal for the future of the federation in Indiana.

Within a very short period, the election became critical to the future of women’s clubs and qualifications for leadership in the Federation. For Clarke and Stimson, the election was also critical in defining whether temperance or suffrage would become the club’s priority. Stimson was closely associated with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and known to be “an antiliquor enthusiast,” whose interest “colors and dominates everything with what she is connected.” While women like Stimson looked to end liquor sales in a feminist effort to protect women and children’s physical safety from drunken husbands, other societies looked to make suffrage their top priority. The difference in conviction was based predominantly on one’s individual background.

In her thesis “Women in Voluntary Service Association: Values and Meanings,” Sarah Katheryn Nathan describes the fundamental incentives behind women’s voluntary associations. She concludes that volunteerism is motivated by personal need. For Stimson, the election meant preserving conservative female values while pushing a temperance agenda. Yet Stimson did not want to muddy her own reputation by seeming fraudulent, and therefore, unsuccessfully, attempted to scapegoat Fairbank on the ballot. For Clarke, supporting Cox consequently challenged the status quo of women’s roles and disassociated temperance agendas to further advance suffrage. Clarke was able to advocate for suffrage, perhaps as a result of her personal privilege and familial influence. Many women in Indiana who led suffrage organizations were financially secure, married to politicians that supported their endeavors, had no children, and were predominantly Protestant. It is also worth analyzing Clarke’s motivations because of her father’s work toward suffrage.

Clarke explained her background in suffrage, stating in a letter to Miss Boswell on May 8, 1914 that “my father had the honor of introducing the very first suffrage amendment in the Congress shortly after the Civil War. This is to show you why I cannot be a trimmer [one who does not commit to a party or issue].” Although historians question whether Julian was in fact the first to propose such an amendment, and though he was ultimately unsuccessful in passing suffrage legislation himself, the extent of her father’s work compelled Clarke to follow in his political footsteps. This aligns with Nathan’s analysis that an individual’s personal background plays a strong role in why and how people are socialized into voluntary behaviors, especially that of how a father’s membership in a group can be a motivating factor for an individual to further a similar cause.

The conflict between temperance and suffrage motivations, regardless of underlying motivation, was put aside occasionally for a common cause. Such solidarity, however, quickly crumbled under what Barbara Springer calls “petty pride.” It was difficult for reform groups to find the right woman who could both delegate authority and inspire loyalty to multiple factions. This was true for Clarke, who was directly situated between club and suffrage groups. Despite the “efficiency, dedication, and zeal” of leaders like Clarke, these women were also, on many occasions, to blame for the failure of early enfranchisement. Historian Dr. Anita Morgan characterizes an example of this failure in her article “The Unfinished Story: Indiana Women and the Bicentennial.” She describes how an early victory for women’s suffrage in Indiana was foregone as state politicians increasingly feared that a vote for suffrage meant a vote in favor of temperance legislation. However clear or not to women that their efforts were weakened by restive factions, women like Stimson, Cox, and Clarke continued to remain monolithic for personal ambition and petty pride.

The 1915 election for president of the Indiana Federation of Women proves that women during the early 20th Century were political beings who were driven by their own personal agendas. By specifically examining how women like Grace Julian Clarke were motivated, influenced, and able to both successfully and unsuccessfully advocate on the local and state level, a more cohesive narrative of the suffrage movement in the United States is formed. It can be concluded that Clarke was heavily influenced by her father’s work toward suffrage at the peak of his political career, and that she likely would not have felt such a strong connection to the goals of suffrage without his influence. The perspectives of archetypal suffragists and clubwomen like Clarke, Cox, and Stimson in Indiana reflect the typically overlooked narrative of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This narrative reflects resistance to the dominant cultural expectations of women during the time to retain a ladylike persona. It simultaneously demonstrates an increasing divergence from such expectations, as seen through their campaign tactics regarding slandering and manipulative politics. In effect, stories of women-dominated politics at a local level complement the larger narrative of suffrage— one that so desperately calls for a three-dimensional evaluation of both private and public achievements.

Further Reading:

Karen J. Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist: True Womanhood Redefined, 1868-1914 (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers), 1980.

Blanche Foster Boruff, Women of Indiana. Indianapolis: Indiana, Indianapolis, Women’s Biography Associations, Mathew Farson, 1941.

Grace Julian Clarke, George W. Julian (Indianapolis: Indiana Heritage Commission, 1923).

Grace Julian Clarke, “George W. Julian: Some Impressions,” Indiana Magazine of History 2, no. 2 (June 1906): 57-69.

Nancy Gabin and Anita Morgan, “Taking Indiana Women’s History into the Twenty-First Century,” Indiana Magazine of History 112, no. 4 (2016): 283-288.

Courtney Grace Gates, History: Indiana Federation of Clubs (Fort Wayne: Fort Wayne Printing Company), 1939.

Grace Julian Clarke Papers, Manuscript and Rare Books Division, Indiana State Library.

Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, Indiana’s 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press), 2015.

Jennifer M. Kalvaitis, “Indianapolis Women Working for the Right to Vote: The Forgotten Drama of 1917,” MA Thesis, Indiana University, 2013.

Anita Morgan, “The Unfinished Story: Indiana Women and the Bicentennial,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 28, no. 4, (2016).

Sarah Katheryn Nathan, “Women in Voluntary Service Associations: Values and Meanings,” MA Thesis, Indiana University, 2013.

Karen Manners Smith, “New Paths to Power: 1890-1920,” No Small Courage: A History of Women in the United States. Edited by Nancy F. Cott (Oxford University Press, 2000), 363.

Barbara A. Springer, “Ladylike Reformers: Indiana Women and Progressive Reform, 1900 to 1920,” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1985.