A version of this post was published in the Indiana Historical Society’s Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 34, no. 4 (Fall 2022).

On the first Monday in November 1801, a landowner named Edward Fentriss entered the courthouse in Randolph County, North Carolina, with a petition of manumission.[1] Edward represented his brother George, who owned two people—Aliff Henley, originally from Virginia, who had been enslaved by the Fentriss family since at least 1779, and her child, Case.[2] When the petition was approved by the “worshipfull County Court of Randolph,” Henley and her son were free from the shackles of slavery.[3]

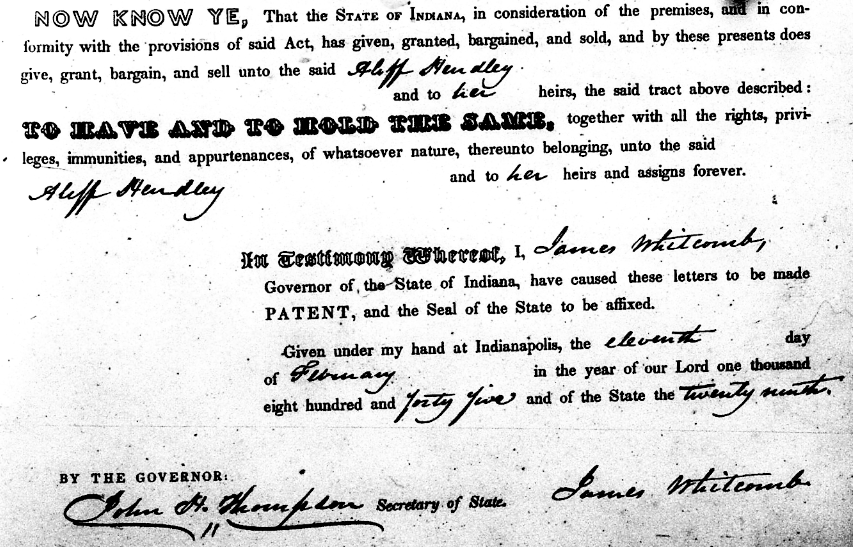

Henley’s story as a newly-free person of color, was destined to reach well beyond its Upper South origins. Indeed, her life now touches hearts and minds in an area far removed from North Carolina. Because on another November morning, forty-three years and 500 miles from bondage, Henley was first in line at the state land office in Delphi, Indiana. There, she paid $280 cash money “in full” for 80 acres in Section 12 of Township 24 North, Range 2 East.[4] On November 11, 1844, with someone helping her enter her name in the Miami Reserve tract book for Canal Lands, Aliff Henley, a woman from North Carolina who endured slavery and could not read or write, became the first known Black American to buy land in Howard County, Indiana.[5] Based on enslavement records and census schedules, it is likely she was born around 1760 in Virginia, making her about 80 when she bought her land.

Tracing Henley’s remarkable journey shows she was still in Randolph County, North Carolina in the 1830 census. But this was a period of migration and by mid-decade she had reached Indiana. Her daughter, Lucinda, married David Rush, another North Carolina native, on June 29, 1837, in Rush County.[6] They continued west and by 1840 were living on Indianapolis’s west side.

In the 1830s and ’40s, Indiana was selling land taken from Native American tribes by treaty to help subsidize the Wabash and Erie Canal. Statewide newspapers published details about available land tracts in the Great Miami Reserve as part of these Canal Land sales.[7] Sometime in 1844 the Rush and Henley families gathered their belongings and headed north to the Miami Reserve.

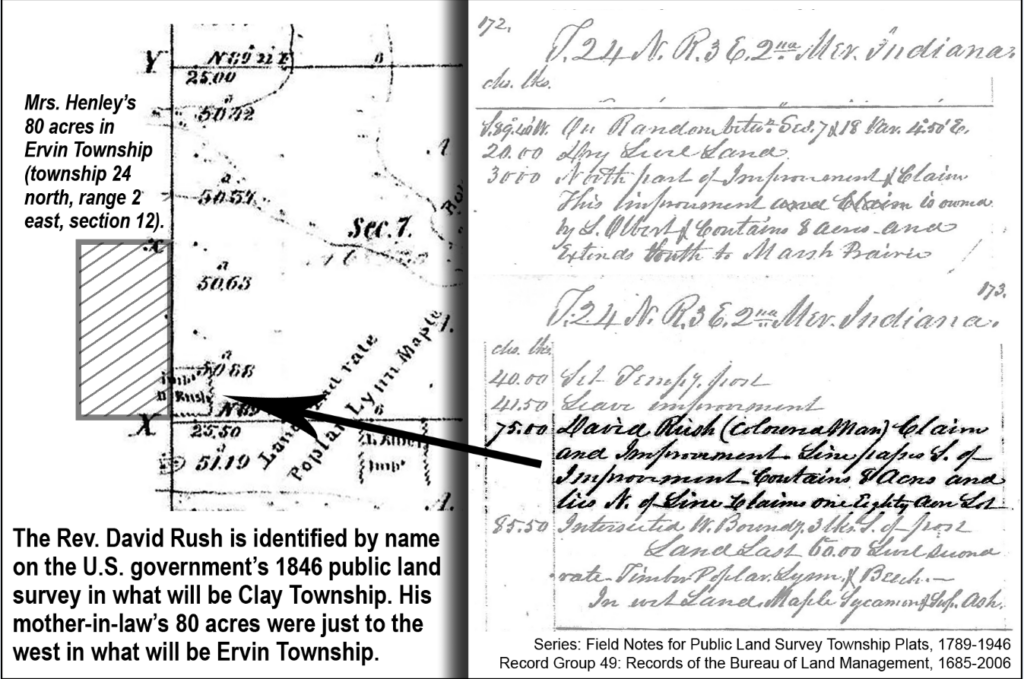

Their arrival resulted in the first of two Black settlements in northwestern Howard County (originally Richardville County, but renamed Howard in 1846). The Bassett and Rush settlements lasted from approximately 1845 to around 1920.[8] The former, centrally located in Ervin Township, is better known. But the earlier and first settlement developed about four miles to the east of Bassett, right on the boundary line (600 County Road West) between Ervin and Clay Townships. Kokomo, the county seat, lay some six miles to the southeast. A brief published history notes the settlement was named for Reverend Rush, described as a “devout and spiritual man, well-versed in the Bible, though entirely unable to read or write.”[9]

According to archival records, Rush settlement originated by at least 1845.[10] Reverend Rush was farming here by then because his name appeared as a squatter with about fifty acres in the U.S. government’s 1846 public land survey.[11] Furthermore, as the small settlement grew, he was one of three named individuals on an 1851 deed entrusted to ensure three-quarters of an acre of land in Ervin Township would be used to “Erect or cause to be Built thereon a house or place of Worship,” which would be the first African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Howard County.[12] The grantor of land was his mother-in-law, adding the AME church to Aliff Henley’s legacy.

Following her 1861 death, Henley deeded her farm to her son, Case, and daughter, Lucinda, (Reverend Rush’s wife).[13] The farm and the rest of the eighty acres were eventually sold. The frame building, where families worshipped and schoolchildren studied, is long gone. Only headstones, including hers, in the graveyard remain—symbolizing stories long waiting to be told.

Henley was a woman who survived enslavement and traveled hundreds of miles in perilous times for Black individuals, purchasing 80 acres of land, in full, on November 11, 1844. She shared her land to build a community and to start a church. Henley was born before a revolution and died the year the Civil War started. Her life is a tribute to the enduring human spirit and perseverance spanning an epoch of American history. Henley is a matriarch of Indiana and Howard County. What better symbol to her memory than the decoration on her tombstone—a rose in full bloom.

Further Reading

Anna-Lisa Cox, The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Black Pioneers & The Struggle for Equality (New York: PublicAffairs, 2018).

Gilbert Porter, “Howard County’s African American Pioneers,” Kokomo Perspective, February 10, 2021, B3, Kokomo-Howard County Public Library, accessed Howard County Indiana Memory Project.

Stephen Vincent, Southern Seed. Northern Soil: African-American Farm Communities in the Midwest, 1765-1900 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999).

Notes:

[1] Record of Slaves and Free Persons, N.C. Archives. File Number: C.R. 081.928. 1 through 6 (#) in The Genealogical Journal 12, no. 38 (The Randolph County Genealogical Society Of The Randolph County Historical Society, Spring 1988): 38.

[2] Edna Hawkins-Hendricks, Black History: Our Heritage Princess Anne County, Virginia Beech, Virginia (self-published, 1998), p. 24, accessed Archive.org.

[3] Randolph County Miscellaneous Records, accessed State Archives of North Carolina.

[4] Aliff Hendley [sic], Certificate #1416, Nov. 11, 1844. Wabash Canal Lands, Register of the Sale of. Oct. 1, 1842 to June 30, 1847. No. 26. Winamac District, Tract Book, Miami Reserve.

[5] Canal Land Patents, Accession #1957006, State Land Office Collection, Indiana State Archives.

[6] Indiana Marriages, 1811-2007, David Rush and Lucinda Henley, 29 Jun 1837; citing Rush, Indiana, United States, Marriage Registration, Indiana Commission on Public Records.

[7] “Sale of Canal Lands,” Logansport Telegraph, September 14, 1844, 2; Indiana State Journal, September 28, 1844, 4.

[8] Early Black Settlements by County, Indiana Historical Society, accessed indianahistory.org.

[9] Rush or Upper Colored Settlement Cemetery Record, Logansport, Indiana. August 18, 1947, L’Anguille Valley Historical & Memorial Association.

[10] “Rush,” Kokomo Gazette Tribune, August 17, 1886, 1.

[11] Field Notes for the Public Land Survey Township Plats, 1789-1946. Record Group 49: Records of the Bureau of Land Management, 1685-2006, accessed Howard County Indiana Memory Project.

[12] Hendley [sic] to Rush & other trustees, Jan. 14, 1851. Deed Book C. Howard County, Indiana. May 1846-Jan. 1856. Pages 374-376.

[13] Aliff Henley’s Will, Sept. 2, 1861. Indiana Wills and Probate Records, 1798-1999. Howard – Will Records. Vols. A and 2.1845-1862. Pages 165-168.

[14] Combination Atlas Map of Howard County, Indiana: Compiled, Drawn and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys, 1877 (Knightstown, IN: Bookmark, 1976), p. 24-25, Historic Indiana Atlases, accessed Indianapolis Public Library.