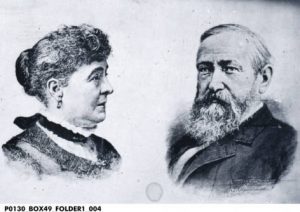

Susan Swain, host of C-SPAN’s special TV series from 2013-2014 on the lives and influence of the nation’s First Ladies, described Caroline Harrison as “one of the more underrated” First Ladies. Caroline Harrison, wife of Hoosier President Benjamin Harrison, served as First Lady from 1889-1892. Previously cast off as simply a tactful housekeeper, historians now recognize that Caroline did more, including using her influence to advocate for the arts, women’s interests, and the preservation of the White House.

On July 4, 1888, Caroline stood next to her husband Benjamin in the parlor of their home on North Delaware Street in Indianapolis surrounded by guests. Caroline had filled the house with patriotic decorations, including red, white, and blue flags and flowers. However, this was not a normal 4th of July celebration: at the party, Benjamin gave a speech, accepting the Republican nomination for president. For the next four months, their home became the center of Benjamin’s political campaign. Parades marched up and down the street in front of the house Benjamin gave more than 80 speeches on their front porch.

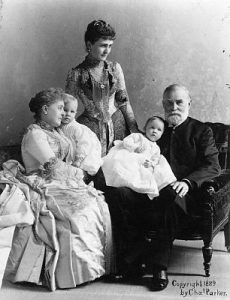

On Election Day, the Harrison family waited anxiously for a telegraph operator set up temporarily in a nearby bay window for election results. The next morning, Caroline and Benjamin discovered they had won. The Harrison family was moving to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

Though the Harrisons had lived in Indianapolis since 1854, the couple’s story began in Ohio. Benjamin had been a student of Caroline’s father at the Farmer’s College in Pleasant Hill, Ohio. Benjamin followed Caroline to Oxford, Ohio. She enrolled in the Oxford Female Institute and he attended Miami University. Soon after they earned degrees, the two got married and moved to Indianapolis.

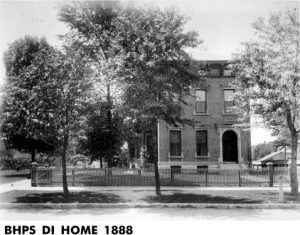

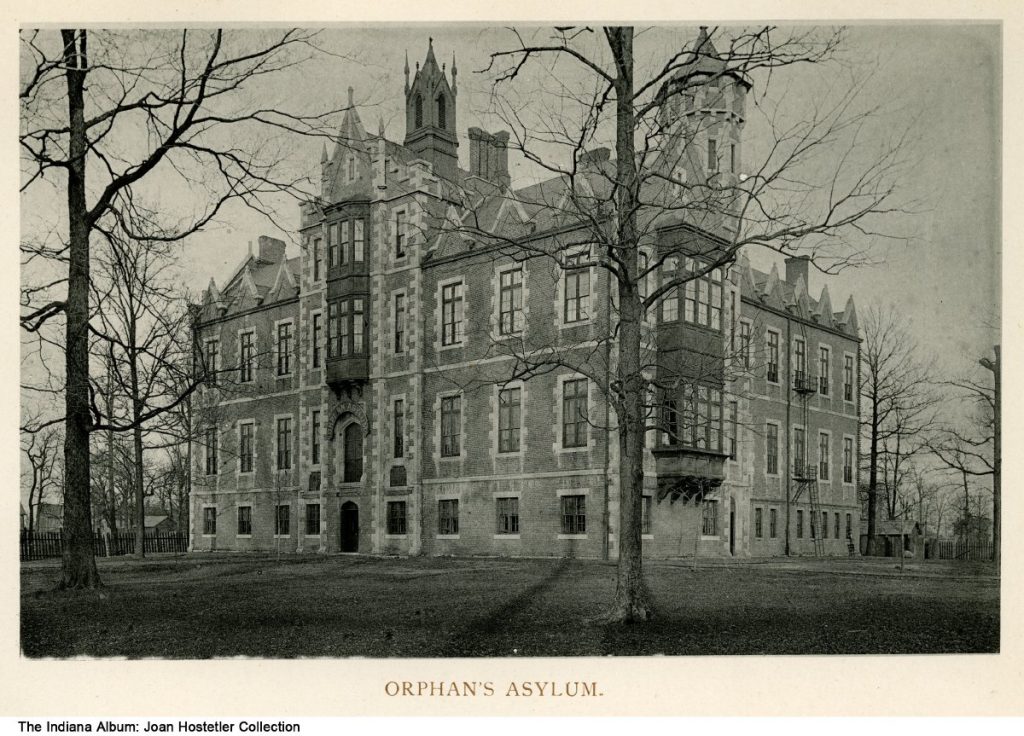

As Benjamin built up his law practice, Caroline became an integral part of Indianapolis’ charity network. Through membership at the Presbyterian Church, Benjamin and Caroline became active in the Indianapolis Benevolent Society, one of the city’s earliest charity organizations. Members were assigned their own district in the city, serving as “donors, fundraisers, friendly visitors and distributors of aid” in their assigned area. During the Civil War, Caroline expanded her efforts, volunteering with various women’s organizations that aided the war effort, like the Ladies Patriotic Association and the Ladies Sanitary Committee. She also started her 30 year long career with the Indianapolis Orphans Asylum, joining the board of managers in 1862. After the war, she became involved with a new charity, the Home for Friendless Women, created to care for an influx of widowed and transient women who flocked to the city after the war. The home operated until 2003, most recently under the name Indianapolis Retirement Home.

Throughout the 1870s, Caroline’s reputation as a capable organizer for charities grew. She sat on the board of many temporary relief funds and charitable events. When Benjamin served as Senator, she added a number of Washington, D.C. charities to her roster, including the Washington City Orphans Asylum and the Ladies Aid Society for Garfield Hospital. An avid painter, she also found time to make pieces to display at early exhibits for the Indianapolis Art Association, which pioneered formal art education in Indiana and influenced the development of fine arts in the state.

When the Harrisons moved to Washington, D.C. for the Presidency, Caroline worked hard to have impact as a First Lady. Though her predecessor, the young and fashionable Frances Cleveland made Harrison look old and dowdy by comparison in the press, Harrison became a more publicly active figure than Cleveland had by advocating for the arts, women’s interests, and the preservation of the White House.

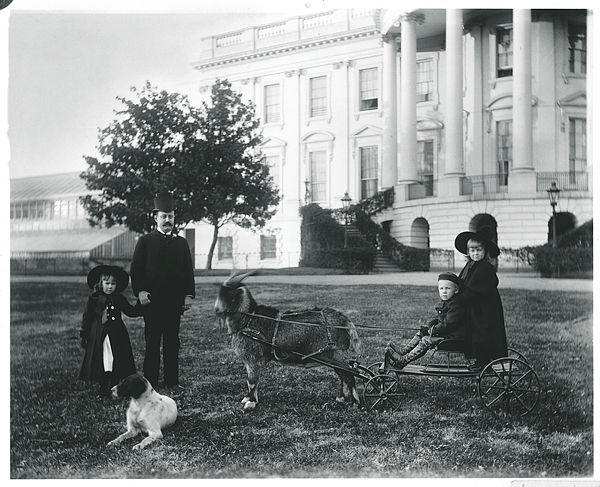

Four generations of relatives moved into the White House when Benjamin took office, which brought the household total up to 12. After the whole family crowded into the White House, Caroline became “concerned over the condition of the house provided for the Chief Executive and his family.” The private spaces for the family amounted to five bedrooms, one bathroom, and a hallway. The rest of the building was reserved for offices and public functions. In addition to the lack of space, the White House had fallen into disrepair. The threadbare carpets, shabby furniture, unwelcome presence of vermin made the White House unsatisfactory to say the least. Caroline reached out to former First Ladies and discovered that previous administrations had struggled with coming up with enough space to entertain and host important foreign leaders and dignitaries. There had been an embarrassing situation during the Buchanan administration where the Prince of Wales and the rest of the royal family could not all be accommodated because of the lack of space.

Caroline began lobbying for congressional funds to refurbish and expand the White House. She gave interviews with journalists and took Senators and Representatives on personal tours of the White House to plead her case. She told reporters,

We are here four years. I do not look beyond that, as many things occur in that time, but I am anxious to see the family of the President provided for properly, and while I am here I hope to get the present building into good condition.

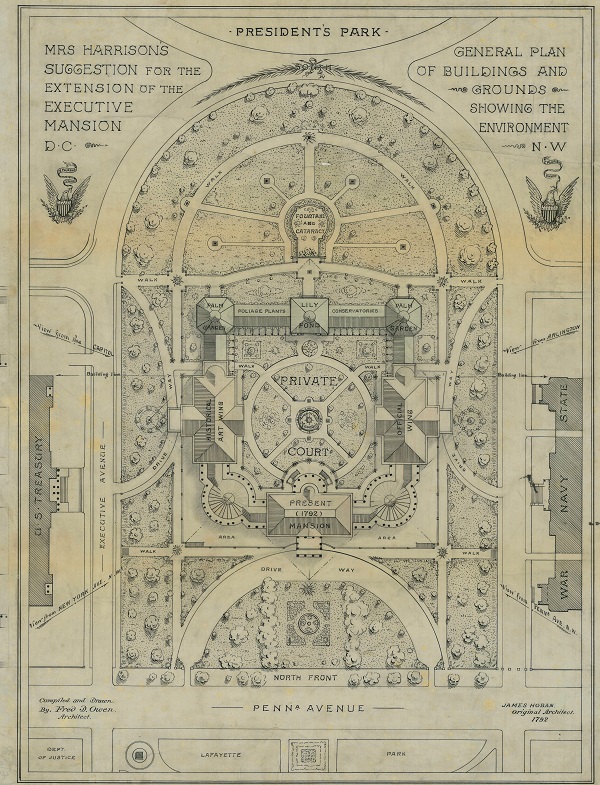

A few Representatives on the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds had already kicked around the idea of expanding the White House. The building had remained largely unchanged since its completion in 1800 (though it was rebuilt after the War of 1812 after the British set fire to it). These Representatives had voiced a number of plans, including adding another story to the White House or constructing an exact replica of the building across the lawn. Some even wondered if an entirely new mansion for the President should be built. Caroline, however, recognized the historical significance of the mansion and articulated a new plan that would preserve the structure. Architect Frederick D. Owen drew up her ideas, which included adding wings to either side of the White House. The press widely circulated her plans, which Owen even titled “Mrs. Harrison’s Suggestion for the Extension of the Executive Mansion.”

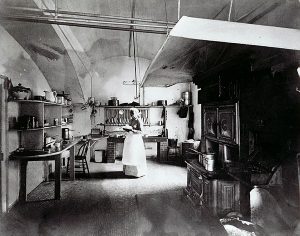

Despite Caroline’s lobbying, her bill to provide funding to expand the White House did not pass. Though it went through the Senate, it failed in the House because President Harrison had ignored the Speaker of the House’s choice for collectorship of Portland, Maine. However, she did receive approximately $60,000 in appropriations to redecorate and renovate the interior and add the first electric lighting. Throughout her First Ladyship, Harrison directed painting, installing additional private bathrooms, renovating the kitchen, replacing all the dirty and moldy floors, rebuilding the old conservatory, adding greenhouses, and redecorating many of the public parlors.

During the renovations, Caroline had the entire contents of the White House inventoried. The Cleveland Leader reported,

Even the old bits stored away in the attic are to be listed, for Mrs. Harrison is anxious that pieces which have historic value or connection with presidential families of the past shall be preserved.

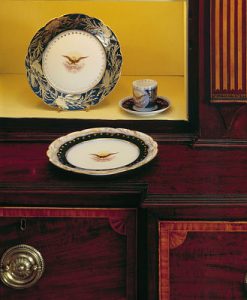

She stopped the old practice of selling off furniture, china, and silver at the end of each president’s administration, not only to save money, but so the historic mansion would maintain pieces from past presidents. Through this process, Harrison laid the foundation for the celebrated White House China Collection. Harrison’s acquaintance, Harriet Foster wrote “she immediately began a valuable collection to be preserved, in cabinets, of the scattered remnants of the china of former Presidents.” She even designed the Harrison china set, which featured corn ears, stocks, and tassels.

Harrison didn’t stop at the White House, but took on additional causes. As First Lady, Harrison advocated the federal government place more emphasis on fine art. She told the Evening Star,

this government has reached that point where it should give more attention to the fine arts—that is, a judicious expenditure for works of merit.

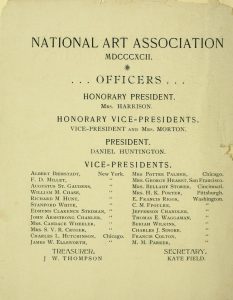

She made sure to include a large gallery of historical paintings in her plans for the White House expansion and supported the addition of paintings to the White House’s fine arts collection, including the first example of a non-portrait piece purchased for the mansion with federal funds. Her plans and actions set precedent for the introduction of a professional curator to care for the White House’s art collection, a position filled during the Kennedy Administration seventy years later. Lastly, in 1892 she became Honorary President of the National Art Association, joining forces with prominent artists like William Merritt Chase and Albert Bierdstadt, to lobby to exempt imported works of art from taxation. The tariff was eventually lifted.

Harrison lent her name to other organizations that promoted women’s interests. She agreed to head a local Washington, D.C. committee of women dedicated to securing women’s admission to the new Johns Hopkins Medical School. Johns Hopkins trustees promised five Baltimore women connected to the institution if they raised $100,000 (later increased to $500,000), the school would accept women on the same terms as male applicants. These women began recruiting prominent women across the nation to raise money in their own locales. According to historian Kathleen Waters Sanders, Caroline’s agreement to help the cause “was important, lending the campaign credibility and national visibility.” Due to women’s work, the medical school opened in 1893 as the first coeducational, graduate-level medical school in the nation.

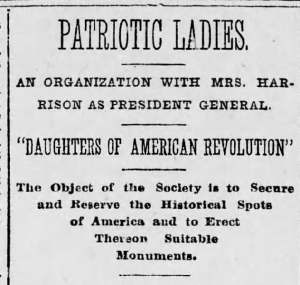

Harrison also agreed to become the first President General of a new organization, the Daughters of the American Revolution. The organization formed in 1890 after the Sons of the American Revolution refused to accept female applicants. The DAR’s goals were “the securing and preserving of the historical spots of America and the erection thereon of suitable monuments to perpetuate the memories of the heroic deeds of the men and women who aided the revolution and created constitutional government in America.”

The founders of the organization asked Harrison to lead, hoping her status as First Lady would elevate the DAR, give it credibility, and attract more members. Though she delegated day-to-day operations to other DAR board members, Harrison helped guide the fledgling organization through its early years and helped it become a political force. In 1892, the DAR had grown from a handful to over 1,300 members. Since 1890, the DAR has accepted over 950,000 members and served as an important political lobbying group. It has also restored and maintained numerous historic sites and preserved countless genealogical records and artifacts.

Unfortunately, Caroline’s career as First Lady was cut short. She died in the White House from tuberculosis October 25, 1892. Benjamin lost reelection soon after. However, a new historical marker at the Benjamin Harrison house in downtown Indianapolis will honor Caroline Harrison’s achievements, both in Indiana and as First Lady. Please check our website and Facebook page for more information about the marker dedication ceremony, scheduled to take place in October.