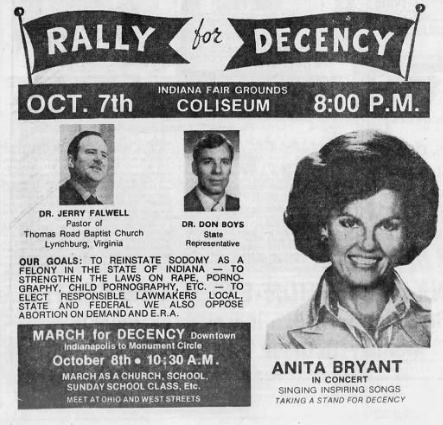

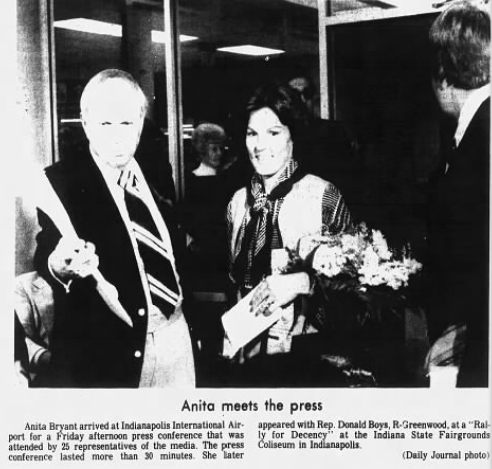

Pop singer, evangelical Christian, and Florida orange juice spokesperson Anita Bryant symbolized the contentious battle over American civil rights and national mores in 1977. Grounded in her religious convictions, she launched the “Save Our Children” campaign, which led to the repeal of a Dade County ordinance that would protect the rights of homosexual residents. That October, Bryant flew to Indianapolis to perform and spread her anti-gay rights message at the “Rally for Decency,” alongside controversial southern pastor Jerry Falwell Sr. and Indiana lawmaker Don Boys, who planned to introduce a bill at the 1978 legislative session that would criminalize sodomy.[1]

From the moment Bryant’s plane touched down to the second she departed the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum, Hoosier journalists and activists pressed Bryant on her opposition to the employment of gay teachers and her advocacy of gay conversion therapy. Like in Indianapolis, her visits to Fort Wayne and South Bend later that month were met with protest, albeit characteristically polite in nature. One of the nation’s leading gay rights activists at the time, Bob Kunst, credited Anita Bryant’s 1977 crusade with forwarding the gay rights movement by normalizing discussions about homosexuality.[2]

Indeed, her efforts to keep gay individuals from obtaining their rights inspired organized resistance in Indiana. The Michiana Human Rights Coalition formed in direct response to her appearance in South Bend. Her visits to the Hoosier state also catalyzed support for gay rights from those outside of the queer community, many of whom may not have given much thought to the plight of this minority group previously. Catholic and cisgender University of Notre Dame Library employee Charles Early explained why he protested her performance on campus in The South Bend Tribune, noting “I joined in a demonstration opposing Anita Bryant on an issue which did not affect me personally because I believe that the spirit which she represents is ultimately a threat to everyone’s rights.”[3]

Here, we examine Hoosier protest to Bryant’s 1977 visits and how similar resistance across the country effectively ended her entertainment career, resulted in the loss of lucrative endorsement deals, and reflected changing national mores.

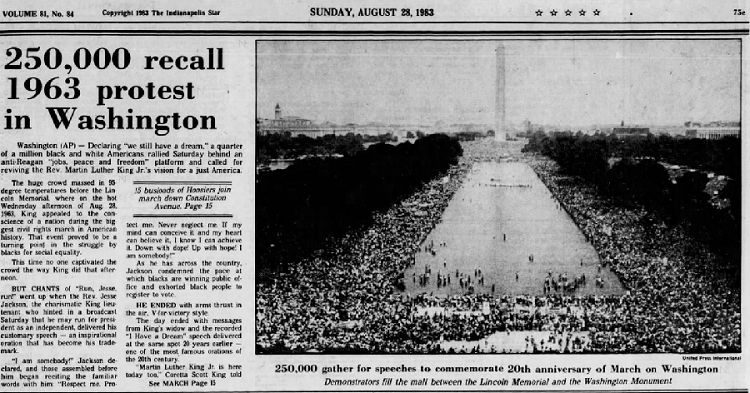

It could be said that the conflicting movements of 1977 constituted a fight for the nation’s soul. Journalist Gloria Steinem, bearing her trademark aviator eyeglasses, mobilized feminists in support of women’s reproductive rights and long-awaited ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which would guarantee equal legal rights for women. Leading counter-protests, conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, “STOP ERA” button dutifully pinned to her lapel, rallied “pro-family” troops at the White House.[4] Occupying the same battlefield as Schlafly was Anita Bryant, who shared her desire to quell the winds of cultural change and safeguard “traditional” American family values. Of this resistance, Early theorized “Many people today are frightened and disturbed by the unrest and rapid change in American society, and they want to go back to a time when things were simpler and more understandable.”[5]

While Steinem and Schlafly sparred over the role and rights of women, Bryant focused on safeguarding the American family by suppressing the rights of gay Americans. Fearing her children would be exposed to the “perversion” of gay teachers, she successfully led a movement to repeal a Dade County, Florida ordinance that would prohibit teachers from being fired due to their sexual orientation.[6]

Anita and her husband Bob Green insisted that they loved gay individuals, so much so that they dedicated themselves to converting them to heterosexuality in order to save them from hell and the “sad” lifestyle they lived. Green recalled:

‘When we were kids, we used to say if a guy was a homosexual, all we had to do was fix him up with a girl and the next day he’d be heterosexual. . . . Well it’s not like that. Anita and I have led many, many homosexuals to the light. But it’s a slow process. It’s an area of sin Christians need to work on.’[7]

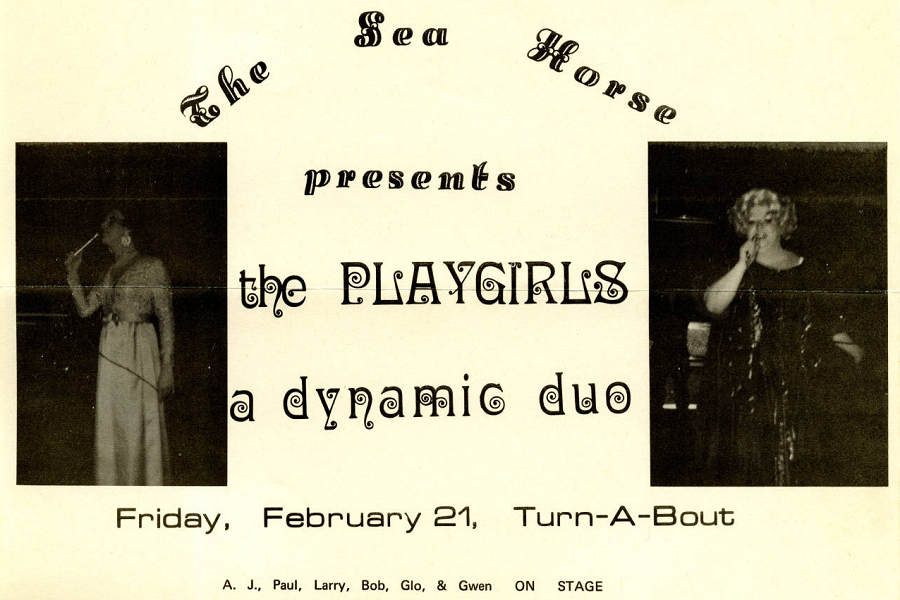

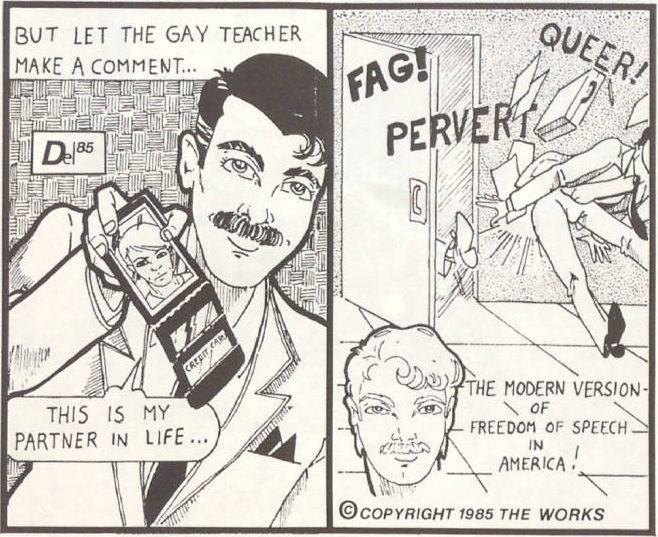

Feeling no love from the devout Christian couple was Ernest Rumbarger, an Indianapolis resident and gay contributor to The Works. He recalled that in the 1970s gay men “were finally learning how to communicate with each other in a social setting other than bars” and that “Gay businesses as such were beginning to flourish and, all in all, things seemed to be going rather well.” That is, until Anita Bryant undertook her “Save Our Children” campaign. Indianapolis police officers arrested Rumbarger and two other men in 1977 for homosexual prostitution in Indianapolis. Rumbarger wrote that he and his partner were two of Bryant’s “better known local victims. We were taken from our home in the middle of the night and held for eight days in jail, incommunicado.” Despite receiving no assistance from the Indiana Civil Liberties Union or Gay People’s Union, a grand jury found Rumbarger not guilty and reportedly offered him an “unsolicited public apology.” The Hoosier wrote “On either coast we would have been carried through the streets and hailed as national heroes” for his triumph over persecution.[8]

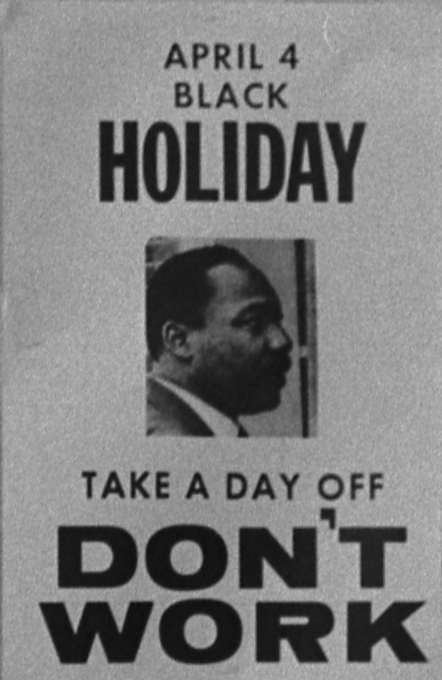

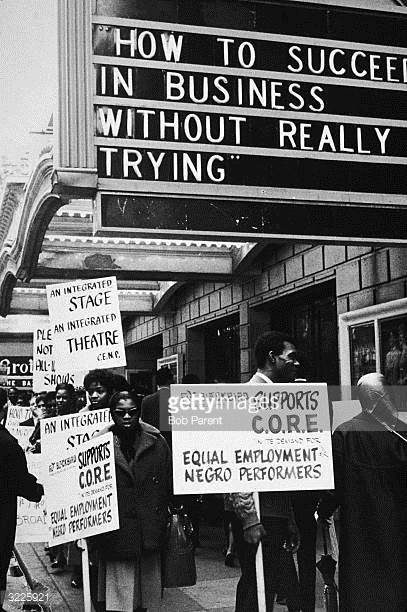

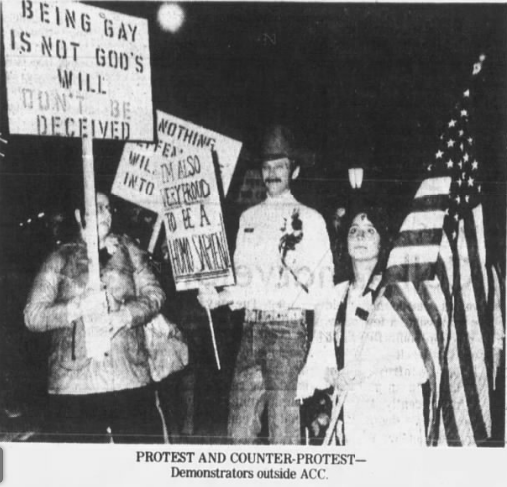

As Bryant’s campaign emboldened harassment of queer individuals, Hoosier allies mounted resistance to her October 7 visit to Indianapolis. The day before the “Rally for Decency,” the Indiana Coalition for Human Rights hosted a news conference, attended by representatives of the Metropolitan Community Church of Indianapolis, Gay People’s Union, and the Sex Information and Education Council of Indiana. Coalition spokesperson Mary Byrne told the press that allies would picket Bryant’s performance “because she represents a force for evil and persecution. She has inflamed irrational prejudices and fostered fear and hatred.” Attending the protest would be Baptist minister Rev. Jeanine C. Rae, who believed that fundamentalists’ attempts to legislate sexuality threatened the separation of church and state. She argued that withholding human rights from certain communities “‘limits the freedom of all persons-including white heterosexual Baptists.'”[9]

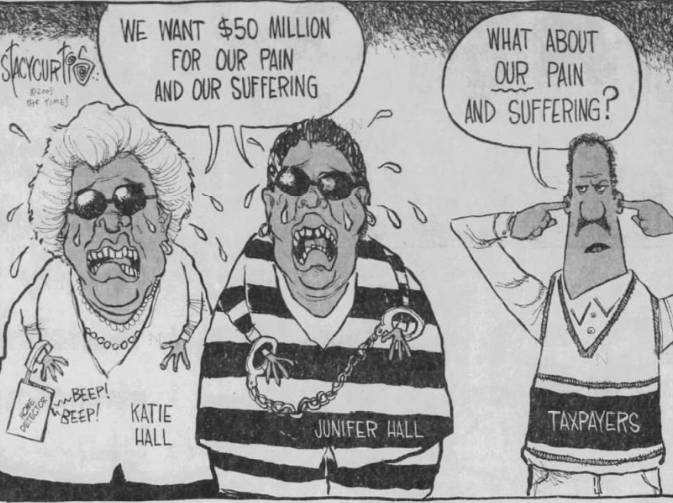

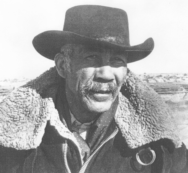

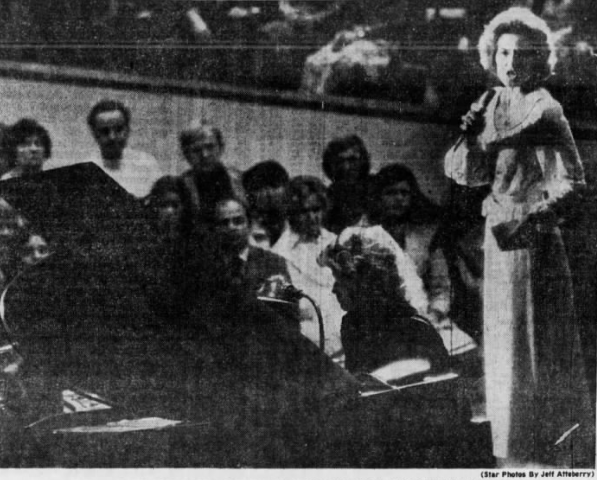

Immediately after arriving at the Indianapolis International Airport on the day of her performance, Anita participated in a press conference, looking, in the words of journalist Robert Reed, “very much like an aging but attractive president of the local PTA.” She and her husband fielded questions about her work to repeal the Dade County ordinance, which she felt afforded gay individuals “special privileges” and would allow them to flaunt homosexuality in the classroom.[10] She believed “God put homosexuals in the same category as murderers, thieves and drunks. Homosexuality is a sin and I’m against all sin. I’m also against laws that give respectability and sanction to these types of individuals.”[11] Her crusade against these laws, she alleged, incited a “national conspiracy” against her. She reported receiving bomb threats and the loss of product endorsements. Reed wrote that her statements were ill-received by journalists, who left the press conference while she was still talking.[12]

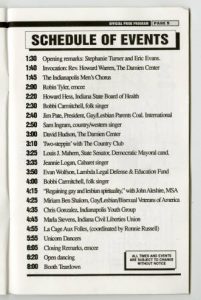

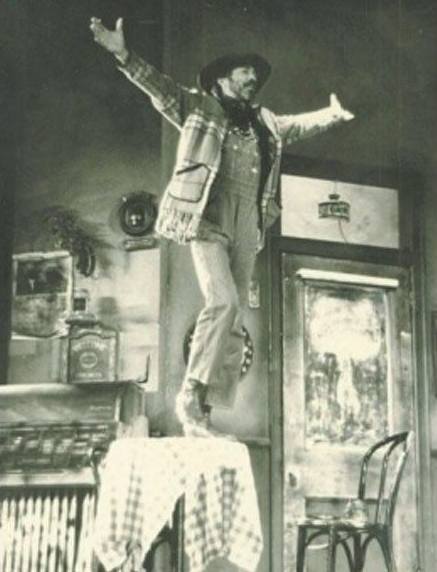

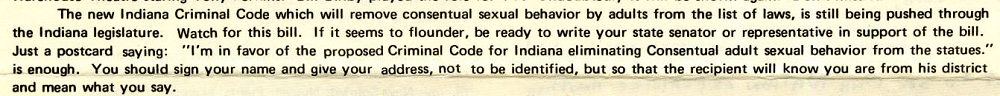

That night, the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum thrummed with cheers and “Amens” as approximately 7,000 attendees absorbed the words of speakers who outlined their plans to “restore decency” in America. The Martinsville Reporter-Times noted that the event “took on the aura of a political rally and a Baptist revival.”[13] Local pastors emphasized the need to elect officials who supported causes like “Save Our Children,” some of whom sat in that very coliseum. Greenwood Rep. Donald Boys advocated for his anti-sodomy law, to be introduced the following year, and for lawmakers to expunge the Equal Rights Amendment. After his bill failed to pass in 1976, the persistent lawmaker wrote, “‘This is the day of equal rights unless you happen to be a Christian, conservative, white male, creationist.’”[14]

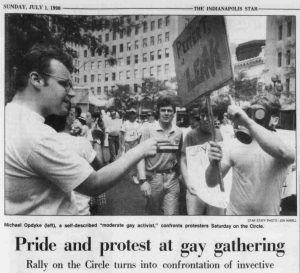

Outside of the coliseum, 500 protesters bore the rain, carrying dampened signs that read “Straights for gay rights” and “A day without human rights is a day without sunshine”— a play on the Florida Citrus Commission’s “Breakfast without orange juice is like a day without sunshine” slogan.[15] Protesters included Fritz Lieber, co-chairman of the Indiana Coalition for Human Rights, who lost his teaching position for being gay. Mary Hoffman, her husband, and three kids also attended the demonstration, believing that Bryant’s message “‘parallels McCarthyism, the Ku Klux Klan and Hitler.'” As protesters stoically made their presence known, Rev. Jerry Falwell quipped on the stage, “It’s a shame it’s raining. It might wash off their make up.”[16]

When at last Bryant took the stage, the audience was rapt, hanging onto every word she sang. She occasionally punctuated her religious and patriotic songs with oration—like warning the audience that “if parents don’t rise up and set standards for our children, the humanists, the ultra-liberals and the militant homosexuals will”—which inspired several standing ovations.[17] After her performance, the polarizing figure departed for Nashville, but the momentum generated at the rally carried over to the next day, when a parade of 500, led by U.S. Marine Cleve McClary, marched to Monument Circle. There, 2,000 Hoosiers joined them for an “encore” rally to “restore decency.” Local pastor Earl Lawson, who worked to reform homosexual individuals and sex workers, declared that he would organize similar rallies across the state.[18]

Opponents responded to the continued rallies through the press. Indianapolis newspapers printed an advertisement compiled by sixty-three clergy protesting “the crusade against persons with homosexual orientation.” A few days after the rally, Jerry Briscoe wrote to the Indianapolis News editor that Bryant’s judgment of others “has become devastating to their existence” and contradicted Christian theology. He stated, “God is our ultimate judge—that is, of course, before Anita Bryant came along.”[19]

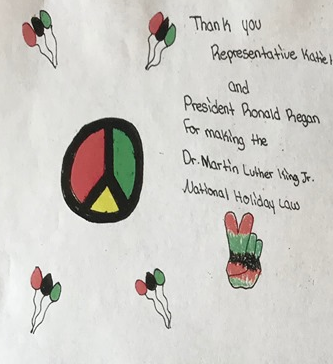

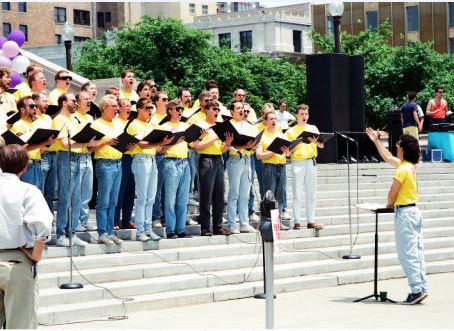

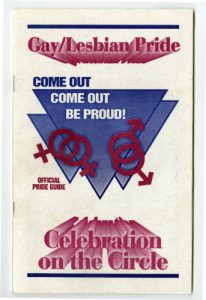

Hoosiers, joined by Cleveland and Chicago activists, again mounted resistance to Bryant when she returned to Indiana at the end of the month. The Michiana Human Rights Coalition formed ahead of her October 26th concert at the University of Notre Dame, with the motto that “All God’s Chillun Gotta Sing.” Protesters planned to march with signs bearing Bible verses and Shakespearean quotes reaffirming human rights.[20] That evening, only 500 of the arena’s 10,000 seats were occupied. The South Bend Tribune reported that Bryant, who led the audience in prayer for gay individuals, unwed couples living together, and divorced couples, “seemed lost in the vastness of the Athletic and Convocation Center.” The number of protesters, both in support of and opposition to Bryant, nearly matched that of concert-goers.[21]

About two weeks before her Notre Dame performance, a protester threw a pie at Bryant during a press conference in Des Moines, Iowa. Her face eclipsed by whipped cream, Bryant tried to pray for the man before breaking down into tears.[22] South Bend demonstrators determined to make their opinions known peacefully and by demonstrating love. They went so far as to invite Bryant to a “gay” reception in her honor, to which she declined. In lieu of pie, they gave her a bouquet of roses and dropped petals at the feet of counter-protesters.[23]

According to Catholic Notre Dame employee Charles Early, the same kindness was not exhibited by counter-protesters, one of whom spat on the seven-year-old daughter of a Michiana Coalition leader. However, Early alleged the “fiasco” that was the concert showed a growing acceptance of the marginalized community.[24] Just three days later, demonstrators picketed Bryant’s performance at Fort Wayne’s Embassy Theater for the 60th anniversary celebration of the Brotherhood Mutual Insurance Co. Some carried signs saying “Gay is Okay” and “Anita Bryant is Proof Orange Juice Causes Brain Damage.”[25]

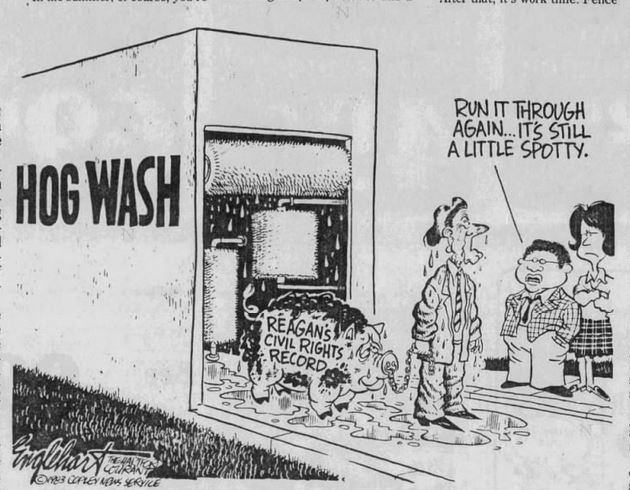

Bryant was met with similar protests across the country and nationwide boycotts of orange juice, endorsed by entertainment titans like Barbara Streisand, John Waters, and Mary Tyler Moore.[26] Gay bars swapped orange juice for apple in screwdriver cocktails. The backlash effectively ended her entertainment career and endorsement deals. She reportedly lost $500,000 in television contracts, was no longer booked for performances, and lost her years-long endorsement deal with the Florida Citrus Commission.[27] Bryant’s crusade ultimately backfired and activists credit her with bringing the issue of gay rights to the forefront. One South Bend Tribune editorial noted that she “stirred a reaction among those whose awareness of and sympathy with the problem previously was minimal but who automatically throw up mental defenses against extremism.” The author wrote that her campaign also prompted examination of the “psychological and physical complexity of homosexuality.”[28]

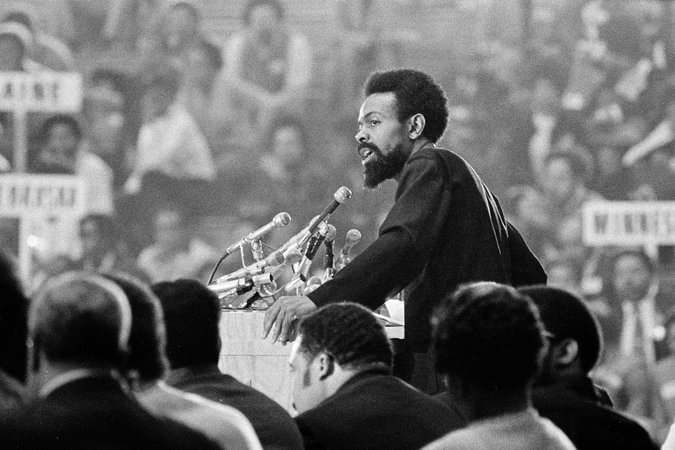

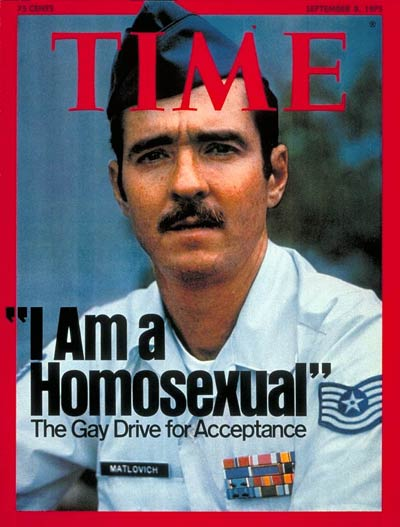

In Louisville, Bryant’s crusade inspired some gay and lesbian residents to cautiously come out of the closet. The thought that “‘We’re all monsters'” inspired one man to be open about his sexuality.[29] Another man interviewed noted that “Anita has made gays aware of themselves.” Reflecting increasingly-tolerant attitudes, that November Harvey Milk became the first openly-gay elected official in California, when he won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. He introduced a gay rights ordinance similar to that which officials repealed in Dade County.[30]

By 1980, Anita Bryant was divorced and financially depleted.[31] Five years earlier, she described the agony of choosing whether to prioritize her family and Christian faith over a career in entertainment.[32] Although she experienced “depressions and doubts, caused by the many sides of me coming into conflict,” prayer revealed to her that she must relinquish ambition and submit to a life of service to her family and Christ. Now shunned by Christian fundamentalists for leaving her marriage, perhaps she related to the lyrics of a song she performed in 1964:

The world is full of lonely people

I know because I’m one of them [33]

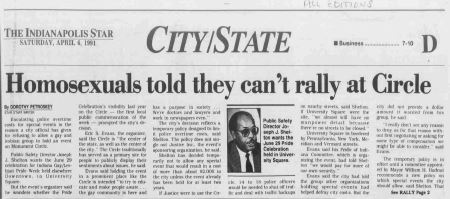

Celebrations resounded in courthouses across the country in 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down same-sex marriage bans in all states.[34] But the 2015 enactment of Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, as well as the 2018 firing of a Roncalli High School guidance counselor upon discovery of her same-sex marriage, again set off passionate debate about religious and civil rights.[35] The events of October 1977 demonstrate that Hoosiers have historically participated in the debate and protested for what they believe is right.

Notes:

* All newspaper articles accessed via Newspapers.com.

[1] Mike Ellis, “‘Standards Must Be Set by Parents,'” Indianapolis News, October 8, 1977, 2.

[2] Interview, “Anita Bryant Confronted in 1977,” Who’s Who, accessed YouTube.

[3] Charles Early, “Counter-protesters at Bryant Concert Warped by Hatred,” South Bend Tribune, November 7, 1977, 15, accessed Newspapers.com.

[4] Karen Karbo, “How Gloria Steinem Became the ‘World’s Most Famous Feminist,'” March 25, 2019, accessed National Geographic.; Douglas Martin, “Phyllis Schlafly, ‘First Lady’ of a Political March to the Right, Dies at 92,” September 5, 2016, accessed New York Times.

[5] Early, “Counter-protesters at Bryant Concert Warped by Hatred.”

[6] Barney Seibert, “Perverts’ Hatred Makes Life Tough for Anita Bryant,” The Reporter-Times (Martinsville, IN), April 10, 1980, 5.

[7] Holly Miller, “‘Deliverance:’ Anita and Mate Tell Their Story,” Anderson Herald, October 8, 1977, 1.

[8] “3 Arrested in ’77 Freed of Charges,” Indianapolis Star, March 9, 1979, 20.; Editorial, E. Rumbarger, “What Do Hoosiers Have to Be Proud of?,” New Works News (June 1989), 4, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

[9] “Anita to Face Pickets Here,” Indianapolis News, October 6, 1977, 3.; Jan Carroll, “Groups Call Miss Bryant Evil Force,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), October 7, 1977, 6.; “Protesters to Be on Hand to Picket Anti-Gay Rally,” Daily Journal (Franklin, IN), October 7, 1977, 5.

[10] Robert Reed, “Anita Bryant: She Draws Line for Hoosier Journalists,” Daily Journal (Franklin, IN), October 8, 1977, 2.

[11] Miller, “‘Deliverance:’ Anita and Mate Tell Their Story.”

[12] Reed, “Anita Bryant: She Draws Line for Hoosier Journalists.”

[13] “Protesters Picket Anita Bryant Decency Rally in Indianapolis,” Reporter-Times (Martinsville, IN), October 8, 1977, 1.

[14] Letter to the Editor, Donald Boys, State Representative, Reporter-Times (Martinsville, IN), June 9, 1977, 2.

[15] Ellis, “‘Standards Must Be Set by Parents.'”

[16] “Anita Stirs Emotions,” Journal and Courier (Lafayette, IN), October 9, 1977, 9.; Ellis, “‘Standards Must Be Set by Parents.'”

[17] Ellis, “‘Standards Must Be Set by Parents.'”

[18] “‘Save Our Society’ Circle Rally Held,” Indianapolis Star, October 9, 1977, 59.

[19] “Anita Stirs Emotions,” Journal and Courier.; Letter to the Editor, Jerry Briscoe, “On Peaceful Coexistence,” Indianapolis News, October 10, 1977, 9.

[20] “Support Grows for Gay Rights, Promoter Says,” South Bend Tribune, October 26, 1977, 14.

[21] Edmund Lawler, “Anita Bryant Revival Draws 500 into ACC,” South Bend Tribune, October 28, 1977, 1.

[22] William Simbro, “Pie Shoved in Anita Bryant’s Face by Homosexual—She Cries,” Des Moines Register, October 16, 1977, 3.

[23] “Support Grows for Gay Rights, Promoter Says,” South Bend Tribune.; Jeanne Derbeck, “‘Gay’ Tactic: Show of Kindness,'” South Bend Tribune, October 17, 1977, 1.; Lawler, “Anita Bryant Revival Draws 500 into ACC.”

[24] Early, “Counter-protesters at Bryant Concert Warped by Hatred.”

[25] “Anita Picketed in Fort Wayne,” Indianapolis News, October 29, 1977, 15.

[26] Fred Fejes, “Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The origins of America’s Debate of Homosexuality (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), accessed Springer Link.

[27] Seibert, “Perverts’ Hatred Makes Life Tough for Anita Bryant.”; N.R. Kleinfield,” Tarnished Images: Publicity’s Great—Up to a Point,” Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, CA), May 26, 1981, 36.

[28] Editorial, “Anita’s Woes,” South Bend Tribune, October 31, 1977, 14.

[29] “Anita Bryant has Opened Doors for Gays,” The Courier-Journal (Louisville), October 6, 1977, 1, 4.

[30] “Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement,” American Experience, accessed PBS.org.

[31] Seibert, “Perverts’ Hatred Makes Life Tough for Anita Bryant.”; Barry Bearak, “Turmoil Within Ministry: Bryant Hears ‘Anita . . . Please Repent,” Miami Herald, June 8, 1980, 1A, 33A.; Steve Rothaus, “Bob Green: Anita’s Ex Paid Dearly in the Fight,” Steve Rothaus’ Gay South Florida, June 9, 2007, accessed Miami Herald.

[32] Alan Ebert, “For Easter: Anita Bryant’s Painful Progress Toward God,” Anderson Daily Bulletin, March 29, 1975, 30.

[33] Lyrics, “The World of Lonely People,” 1964, accessed Genius.com.

[34] Ed Payne, “Indiana Religious Freedom Restoration Act: What You Need to Know,” CNN, March 31, 2015, accessed CNN.com.; Bill Chappell, “Supreme Court Declares Same-Sex Marriage Legal in All 50 States,” The Two-Way, June 26, 2015, accessed NPR.org.

[35] Arika Herron, “Shelly Fitzgerald, First Gay Guidance Counselor Suspended by Roncalli, Files Federal Suit,” IndyStar, October 22, 2019, accessed IndyStar.com.