The renowned historian Howard Zinn called dissent “the highest form of patriotism.” He explained:

In fact, if patriotism means being true to the principles for which your country is supposed to stand, then certainly the right to dissent is one of those principles. And if we’re exercising that right to dissent, it’s a patriotic act.[1]

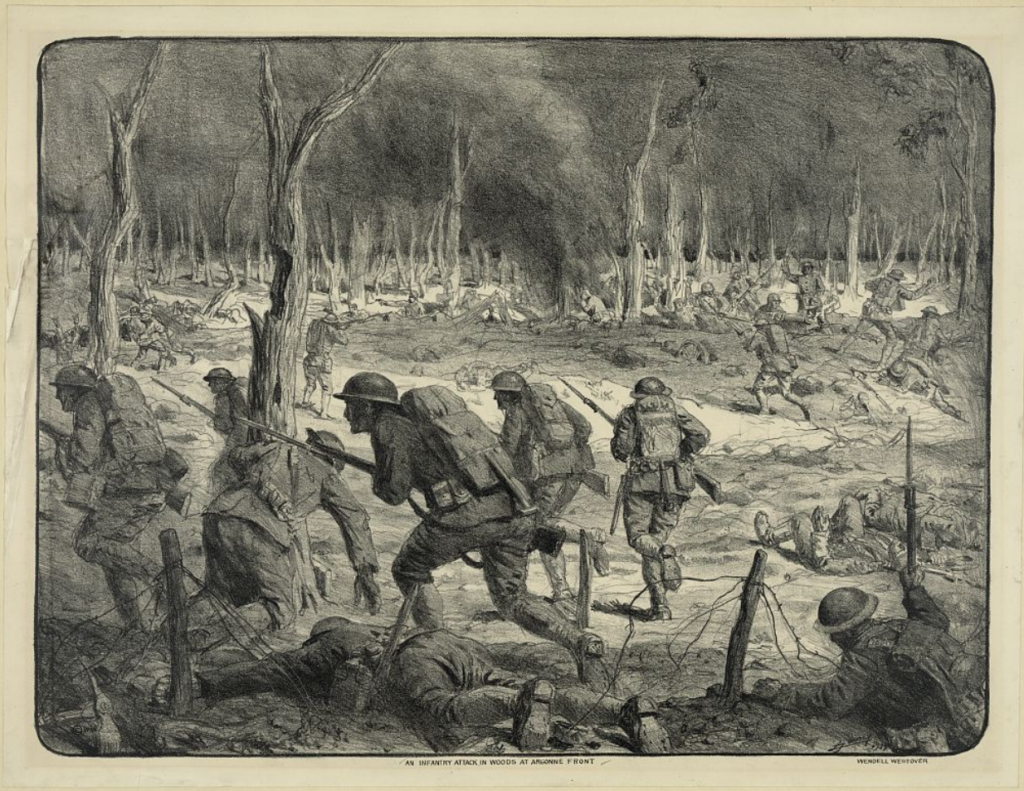

The Hungarian immigrants who came to Terre Haute at the turn of the twentieth century made dissent their first act of patriotism, striking and organizing for equality in the workplace. After the U.S. declared war on Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary in 1917, however, these Hoosiers of Hungarian origin temporarily abandoned this cause for another – demonstrating their loyalty to the United States and becoming citizens. This battle for acceptance was almost as fierce as the violent skirmishes at the nearby coal mines.

Escaping impoverished conditions in Hungary, over a million Hungarians immigrated to the United States between 1870 and 1920, according to one study.[2] By 1910, over 14,000 Hungarian immigrants settled in Indiana with 452 in Vigo County, creating a vibrant community in Terre Haute.[3] The language barrier combined with local mistrust of Eastern European immigrants meant that their job options were limited. But industry in the city was booming, creating a demand for workers willing to take on the difficult and dangerous jobs in coal mining, manufacturing, and railroads.[4] Newspapers across the country are full of stories of workers killed in factory explosions or coal mine cave-ins.[5] Few companies had adequate safety regulations and none had insurance. So, the newcomers took care of each other.

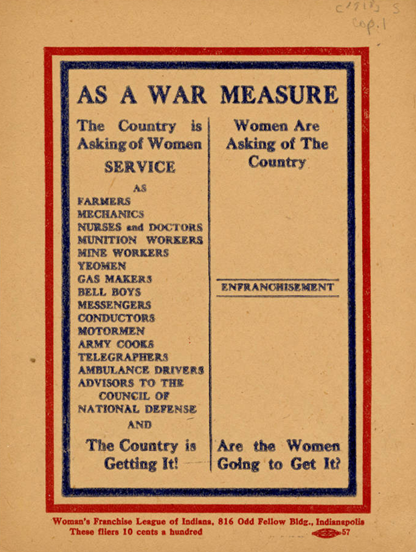

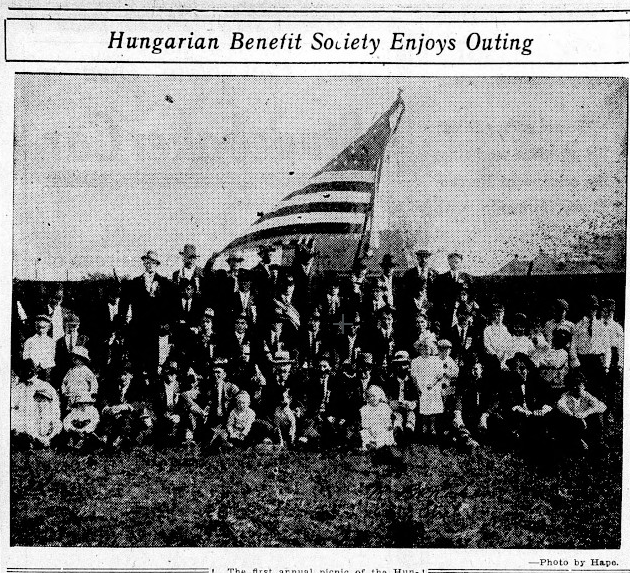

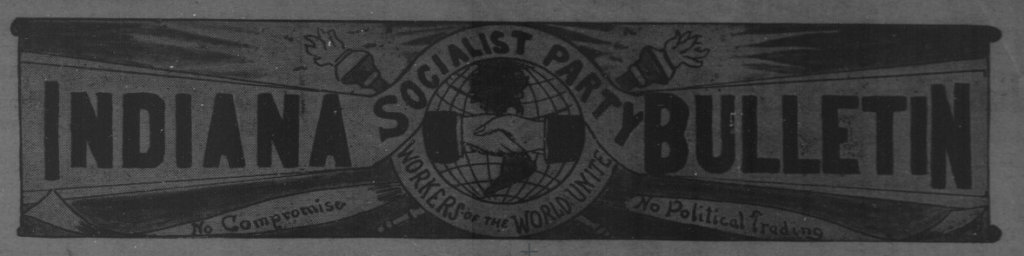

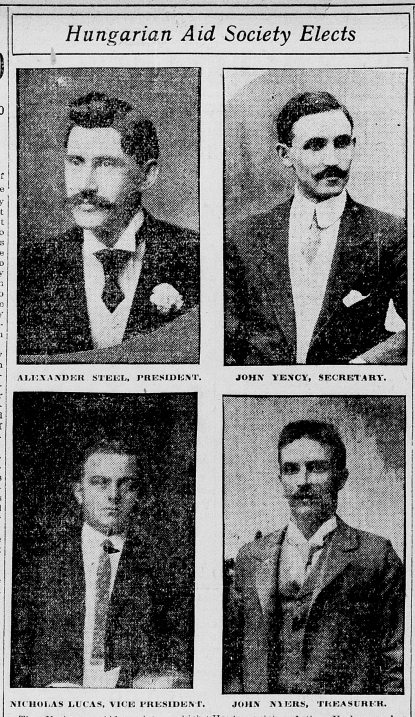

In 1909, they formed the First Terre Haute Hungarian Sick and Death Benefit Society, a self-funded insurance group (also known as the Verhovay Society).[6] The approximately 200 members paid regular dues with the funds going to the families of members when they were killed or injured at work.[7] Hungarian immigrants were willing to take the risk, hoping to improve the lives of their families. However, in addition to the dangers, companies were also paying the immigrants lower wages. These were people eager to become citizens of the United States – a country that promised “all men are created equal,” according to the Declaration of Independence.[8] This disparity in pay did not reflect the proclaimed values of their new country. In response, the Hungarian immigrant workers joined labor unions and Socialist Party organizations and went on strike for better wages.[9] Between 1905 and 1910, Hungarian immigrants participated in seventy-seven of the 113 strikes that occurred nationwide, according to one study.[10]

However, in the spring of 1909, they were violently suppressed. Several men of Hungarian origin worked at the nearby Bogle coal mine where they lived in camps. For several weeks they had clashed with the American-born workers. While there are plenty of newspaper articles covering the clashes, it’s unclear what generated the feuds.[11] Looking at other similar events across the country, it is likely that the immigrant workers were pushing for equal pay, while the American workers resented them for working for low wages, inhibiting their own ability to demand higher compensation. Many companies would gladly replace a higher American wage with a lower immigrant one.[12] Unfortunately for both groups of workers, deep-seated xenophobia prevented the two groups from uniting and demanding fair pay for all. Instead, they turned on each other. On March 31, the Associated Press reported that the American coal miners had driven the Hungarian immigrant workers from the Bogle mine after “a gun fight . . . in which eleven persons were wounded.”[13] The Hungarians would have to tend to their wounded and seek jobs elsewhere.

Some of the Hungarian workers who remained in Terre Haute organized a local branch of the Indiana Socialist Party and attended meetings on workers’ rights.[14] But in 1914, the outbreak of war in Europe would curtail all such patriotic dissent. The newcomers would demonstrate a new kind of patriotism and their organizations and leadership quickly shifted their goals and tactics. The nationalism surrounding WWI required them to display their unquestioned allegiance to the United States in a public, performative manner. Following the activities of local Hungarian organizations and leaders in the Terre Haute Daily Tribune, it’s clear that the newcomers felt their main goal was to convince their neighbors that they were Americans first and foremost and Hungarians only culturally. In the pages of the Daily Tribune, they publicly disavowed their allegiance to the ruler of Austria-Hungary and made clear that they disagreed with the crown’s position in the war.[15]

The Verhovay Society also took on additional duties during WWI. They hosted English classes and events, displaying their patriotism by flying large American flags at their meetings and picnics.[16] Most importantly, many Hungarian-born Terre Haute residents pursued citizenship. As soon as they met the residential requirements, they applied for first papers. At this time, in Indiana (and thirty-nine other states) immigrants with first papers could vote in all elections.[17] They would then study English, American history, and the workings of the U.S. government in preparation for their citizenship tests. The Daily Tribune regularly reported on their citizenship applications.[18]

These citizenship efforts became more important after the U.S. entered the global conflict, first declaring war on Germany, and then, in December 1917, on its ally Austria-Hungary. The U.S. federal government then declared Hungarian immigrants who had not yet achieved full citizenship to be “enemy aliens.” According to the National Archives:

The Federal Government instituted enemy alien control programs during wartime. This generally subjected aliens to additional regulations, increased scrutiny, and required registration and/or internment.[19]

Nationalism flared and immigrants, especially those from Germany and Austria-Hungary, felt the repercussions – often through the loss of rights. Indiana schools stopped teaching German, while German-language newspapers in Terre Haute and across the state folded.[20] Hoosiers consumed propaganda vilifying Germany and its ally Austria-Hungary. President Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of war included regulations for “alien enemies,” including barring firearm ownership and allowing for arrest and detainment for the duration of the war.[21] This was not an idle threat.

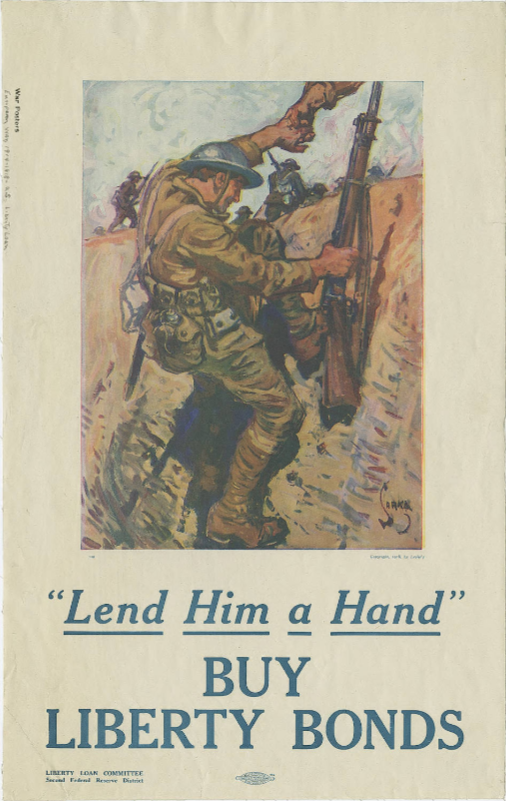

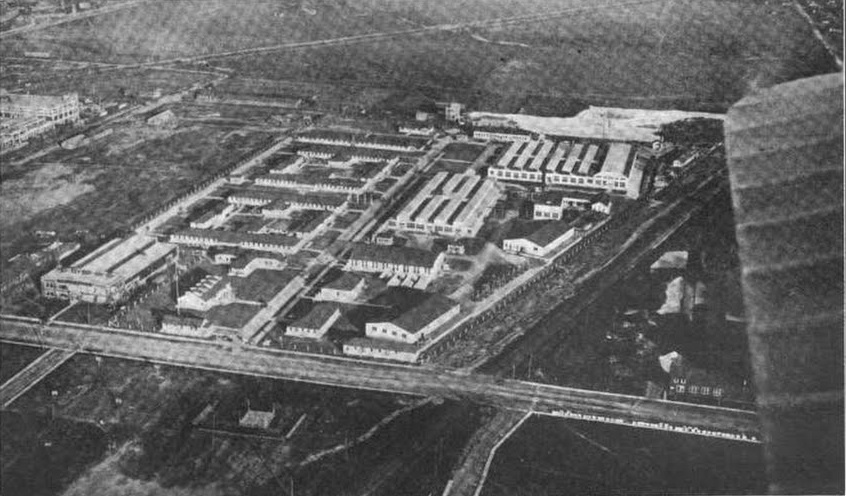

Many of the Hungarian immigrants to Terre Haute worked for Terre Haute Malleable & Manufacturing Company (incorporated in 1906) and settled in the neighborhood near the plant.[22] In June 1918, Terre Haute police arrested Austrian-born Malleable employee John Precpep. The Daily Tribune reported that he was charged with being “a suspected dangerous alien enemy” and would be “interned for the duration of the war.”[23] He was also made to turn over his property and the $1,000 he had in the bank. He was reported to have bought no Liberty Bonds and to have “encouraged foreign born citizens to evade the draft law.” [24] It’s not clear who made these reports – neighbors or coworkers perhaps. But it is clear that one’s reputation as a loyal, patriotic American – one who bought war bonds and registered for the draft – mattered. But even enlisting in the U.S. Army didn’t necessarily protect one from suspicion.

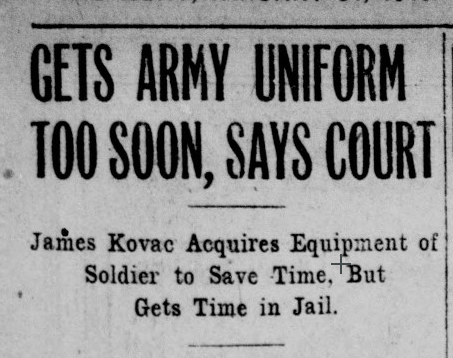

Hungarian Terre Haute resident James Kovac enlisted in the U.S. Army and proudly carried his registration card with him around town. He also went to a second hand store and bought himself an army coat and bayonet “so that the government would not have to furnish him one when he enlisted.”[25] Wearing his hand-me-down uniform with pride, Kovac attended a dance at a local establishment at 15th and Beech Streets. When the tavern owner identified Kovac as Hungarian, he called the police. Kovac was arrested for carrying a concealed weapon. Local courts determined that he got his “army uniform too soon” and sentenced him to 100 days in jail, despite his eagerness to serve his new country.[26] So if enlisting wasn’t the ultimate expression of loyalty, what was? How could immigrants of Hungarian origin display their patriotism to neighbors and coworkers and avoid reprisals for failing to do so?

Leading Terre Haute citizens of Hungarian origin organized highly visible displays of patriotism, which the local newspaper reported on approvingly. In June 1917, the Verhovay Society, led by Alexander Steele, “held a flag dedication” at the organization’s “picnic grounds” at Twenty-Second and Linden Streets (today the site of Hungarian Hall).[27] The Daily Tribune reported that “the affair was one of the biggest celebrations ever held by foreign organizations.”[28] In addition to the hundreds of local Verhovay members, Clinton (Vermillion County) also sent a delegation of 300 members. In addition to prominent members of the Hungarian community, the mayor of Terre Haute, the reverend of St. Ann’s Church, and the captain of a local military company also attended. During the ceremony the Society officially adopted the American flag and vowed to carry it “at all public demonstrations hereafter.”[29]

In June 1918, Alexander Steele led another display, this time “a patriotic parade” and an assembly at the Terre Haute Post Office where the resident of Hungarian origin would “renew their oaths of loyalty to this country under the American flag.”[30] They also announced that they would be forming a Hungarian Loyalty League. Just a month later, the League marched in the Fourth of July parade. The Daily Tribune reported that the 160 members who marched carried a large American flag and “were repeatedly cheered along the line of the march.”[31] Later that month, they held their largest and most visible event yet.

On July 27, 1918, 250 members of Terre Haute’s Hungarian Loyalty League swore a public “oath of allegiance to the Stars and Stripes.”[32] This act was accompanied by hundreds more supporters marching in a patriotic parade from Ninth and Ohio Streets to the post office. Symbolizing the approval of the community and the sanction of local officials, the parade was headed by “a platoon of police.”[33] They were followed by “a party of mounted Hungarians and then came the First Regiment band.”[34] At least 200 Hungarian men marched as did an uncounted number of women and children, followed by decorated automobiles. They carried American flags and banners reading “Help Win the War,” “We Are Ready to Give Our All of America,” and “Hungarians by Birth, Americans by Choice.”[35] The Daily Tribune reported that the parade was directed by League President Alexander Steele, the local Postmaster John J. Cleary, and the Terre Haute mayor Charles R. Hunter. The newspaper noted approvingly:

Mr. Steele deserves great credit for the rousing display of patriotism shown by himself and his countrymen and their loyal support of the stars and stripes.[36]

After swearing the oath, Terre Haute residents gave them “a rousing cheer.” The party then “adjourned to their hall” (likely a precursor of the current Hungarian Hall) at 22nd and Linden.[37] There they celebrated with a banquet, dancing, and speechmaking.

Despite such performances of patriotism, Indiana soon moved to end the right of immigrants to vote on first papers and authorities broke up meetings of “foreign born . . . bolshevik agitators” as Hoosiers succumbed to the fear and nationalism of the First Red Scare.[38] Ku Klux Klan membership grew dramatically in the early 1920s and Indiana’s representatives in Congress voted for the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which effectively ended immigration from Eastern Europe.[39] But even in this cultural climate, the Hungarian community of Terre Haute thrived. They continued to pursue citizenship and improve their English, opening up more occupational opportunities for themselves and their children. They saved money and opened small shops, including a number of grocery stores. There are many examples of this trajectory, including that of Frank and Julia Koos.

Ferencz Koos and Julianna Majoros immigrated through Ellis Island in 1907 and 1910, respectively. They married, Americanized their names, moved to North Carolina, and then Indiana. By the early 1920s, they had made Terre Haute their home. Frank worked as a miner and a farmer and the couple saved their money. By 1925, they had opened a small grocery store at 2401 Maple Ave in the Hungarian neighborhood. While the business was named Frank Koos Grocery & Meats, the city directories and census records show that Julia managed the day to day operations while Frank continued working in coal mines. Later in life, when the store was comfortably established, they shared the running the shop as well as a small farm.[40]

The site where Koos’s store once stood is the perfect location to place a historical marker with this family’s story symbolizing the experiences of many in the city’s Hungarian community. Thanks to a successful marker application by the Koos’s granddaughter Laura Loudermilk, and the work of IHB staff, a state historical marker will be dedicated later this year. The text will read:

Side One

Hungarians seeking economic opportunities settled in Terre Haute at the start of the 20th century and created a vibrant community. Many worked for coal mines, railroads, and manufacturing industries. In response to dangerous conditions and low wages, they joined unions and, in 1909, founded the Hungarian Sick and Death Benefit Society, a self-funded insurance group.

Side Two

Despite facing prejudice during WWI, many Hungarian immigrants enlisted in the military, formed patriotic groups, and gained citizenship. They also established businesses, including Frank and Julia Koos who opened a grocery store here in the 1920s. Nearby Hungarian Hall hosted celebrations, elections, and union meetings, and continues to preserve Hungarian traditions.

The marker will stand as a reminder that these Hungarian immigrants, once designated “alien enemies,” improved their community and local economy, served their new country in times of war, and made Terre Haute a more vibrant and diverse city. Immigrants revitalize local economies and make communities stronger, according to the National Academy of Sciences (NAS). [41] The story of the contributions made by Terre Haute’s Hungarian community is a good reminder for us today as newcomers from other countries look to make Indiana their new home.

Further Contextual Reading:

Susan Papp and Joe Esterhaus, Hungarian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland (Cleveland State University, 2010), electronic edition accessed Press Books at the Michael Schwartz Library, https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/hungarian-americans-and-their-communities-of-cleveland/.

Notes:

[1] Howard Zinn interviewed by Sharon Basco, July 3, 2002, HowardZinn.org.

[2] Leslie Konnyu, Hungarians in the U.S.A.: An Immigration Study (St. Louis, MO: American Hungarian Review), 1967, 22, Archive.org.

[3]”Foreigners in Indiana,” Bedford Weekly Mail, May 17, 1907, 3, Newspapers.com; Department of Commerce and Labor, Thirteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1910: Statistics for Indiana (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913), 598, 614, census.gov.

[4] Table: “Fatal Accidents in Vigo County,” and Table: “Serious Accidents in Vigo County,” in “Summary of Accidents, 1913,” Second Annual Report of the State Bureau of Inspection (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, State Printer, 1914), 404-06, HathiTrust.

[5]“Dead Hungarians,” Crawfordsville Weekly Journal, April 4, 1891, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Many Killed by Bursting Boilers,” Pittsburg Press, December 20, 1901, 1, Newspapers.com; “Fifty Bodies Still in Mine,” Miners Journal, January 29, 1904, 1, Newspapers.com; Beverly N. Sparks, “Brave Rescuers at the Darr Mine Face to Face with Awful Death” and C. H. Gillespie, “Disaster Blamed on Company,” Pittsburg Press, December 22, 1907, 1, Newspapers.com; “Nine More Bodies Taken from Monongah Mines Making the Total Recovered 52,” Daily Telegram, December 9, 1907, 1, Newspapers.com.

[6] R. L. Polk and Co’s Terre Haute City Directory 1912-1913 (Terre Haute: Moore-Langen Printing Co., 1912), 66, AncestryLibrary.com; R. L. Polk and Co’s Terre Haute City Directory 1915-1916 (Terre Haute: Moore-Langen Printing Co., 1915), 222, AncestryLibrary.com; “Notes of Local Lodges,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, December 14, 1914, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hungarians Elect,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, December 7, 1915, 6, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hungarian Benefit Society Enjoys Outing,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 18, 1916, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[7] “Hungarian Aid Society Elects,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, December 20, 1914, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[8] Declaration of Independence, transcription, July 4, 1776, Founding Documents, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

[9] “Hungarian Branches,” Indiana Socialist Party Bulletin, July 1, 1913, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Federal Authorities Probe Clinton Case,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 14, 1919, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Now on Trail of East Chicago Reds,” Indianapolis News, October 13, 1919, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Issues Injunction Against Molders,” Indianapolis Star, Mary 26, 1923, 5, Newspapers.com; “Labor Troubles Ripe in Three Indiana Cities,” Hammond Times, August 17, 1935, 6, Newspapers.com.

[10] Miklos Szantho, Magyarok a Nagyvilágban (Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1970), 66 in Susan Papp and Joe Esterhaus, Hungarian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland (Cleveland State University, 2010), electronic edition accessed Press Books at the Michael Schwartz Library, https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/hungarian-americans-and-their-communities-of-cleveland/.

[11] “Eleven Wounded,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), March 31, 1909, 1, Chronicling America, Library of Congress; “Mine Is Threatened,” Winchester News (KY), March 31, 1909, 5, Chronicling America, Library of Congress; “Threatened War between Miners Not So Critical,” Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram, March 31, 1909, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[12] “The Great Immigration,” Section II: Hungarians in America in Hungarian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland, pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu.

[13]”Eleven Wounded,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), March 31, 1909, 1, Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

[14] Hungarian Branches,” Indiana Socialist Party Bulletin, July 1, 1913, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; Partial Transcript of Interview with Frank Koos, 1968, Private Collection of Laura Beth Loudermilk, copy in IHB marker file.

[15] “Hungarian Position in War in Europe,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, August 21, 1914, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[16] “Hungarian Benefit Society Enjoys Outing,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 18, 1916, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; Curt Bridwell, “What Terre Hauteans Read in the Newspapers of 40 Years Ago,” Terre Haute Tribune, December 11, 1949, Newspapers.com.

[17] “Naturalization Records,” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/naturalization.

[18] “New Citizens Are Sworn In,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, November 15, 1914, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Citizenship Applications of Four Are Turned Down, Terre Haute Daily Tribune, November 14, 1915, 21, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Four File Declarations,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, April 17, 1917, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Seeks Citizenship,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, May 24, 1917, 16, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[19] “Enemy Alien Records,” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/enemy-aliens.

[20] Indiana Historical Bureau, German Newspapers’ Demise, state historical marker #49.2017.2, in.gov.history.

[21] “World War I Enemy Alien Records,” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/enemy-aliens/ww1.

[22] “Incorporation” Indiana Tribune, August 4, 1906, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wanted,” Indianapolis News, December 22, 1906, 19, Newspapers.com.

[23] “Will Intern Austrian for War’s Duration,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 25, 1918, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Gets Army Uniform Too Soon, Says Court, Terre Haute Daily Tribune, 11, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Hungarians Dedicate the American Flag,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 9, 1917, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Hungarians Raise Flag,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 6, 1918, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[31] “Bulgarians Are Loyal,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, July 5, 1918, 18, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[32] “Loyal Hungarians Pledge Allegiance,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, July 28, 1918, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “Federal Authorities Probe Clinton Case,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 14, 1919, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “No Alien Enemy Voters,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, October 13, 1918, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles.

[39] Jill Weiss Simins, “‘America First:’ The Indiana Ku Klux Klan and Immigration Policy in the 1920s,” Journal for the Liberal Arts and Sciences 25, Issue 1 (Fall 2020), Oakland City University.

[40] Passenger Record: Ferencz Koos, May 1, 1907 Arrival Date, Ellis Island Passenger Records, ellisislandrecords.org; Passenger Record: Julianna Majoros, December 3, 1910 Arrival Date, Ellis Island Passenger Records, ellisislandrecords.org; Fourteenth Census of the United States, Burgaw Township, North Carolina, January 26, 1920, 17A, Lines 39-40, Bureau of the Census, National Archives and Records Administration, AncestryLibrary.com; Polk’s Terre Haute City Directory 1922 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1922), 403, AncestryLibrary.com; Polk’s Terre Haute City Directory 1924 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1924), 423, AncestryLibrary.com; Polk’s Terre Haute City Directory 1925 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1925), 334, AncestryLibrary.com; Frank Koos Grocery and Meats, photograph, n.d. [circa 1929], Private Collection of Laura Beth Loudermilk, copy in IHB marker file; Fifteenth Census of the United States, Ward 7, Terre Haute, Vigo County, April 8, 1930, 4A Lines 44-45, Bureau of the Census, National Archives and Records Administration, AncestryLibrary.com; Sixteenth Census of the United States, Ward 7, Terre Haute, Vigo County, April 2, 1940, 1B, Lines 64-64, Bureau of the Census, National Archives and Records Administration, AncestryLibrary.com; Polk’s Terre Haute City Directory 1947 (St. Louis: R. L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1947), 269, AncestryLibrary.com; Partial Transcript of Interview with Frank Koos, 1968, Private Collection of Laura Beth Loudermilk, copy in IHB marker file.

[41] National Academy of Sciences, “Integration of Immigrants into American Society” (Washington, D.C.: NAS Press, 2015), https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/21746/chapter/1.