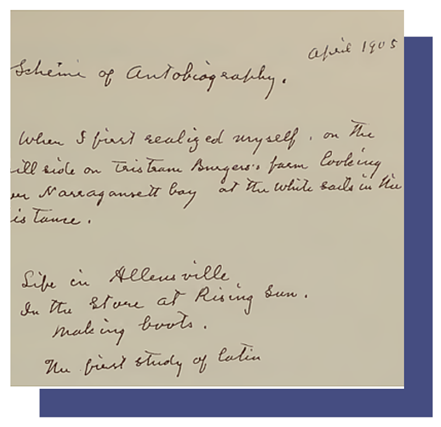

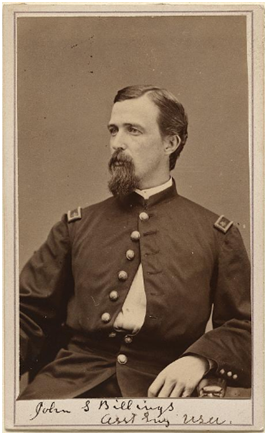

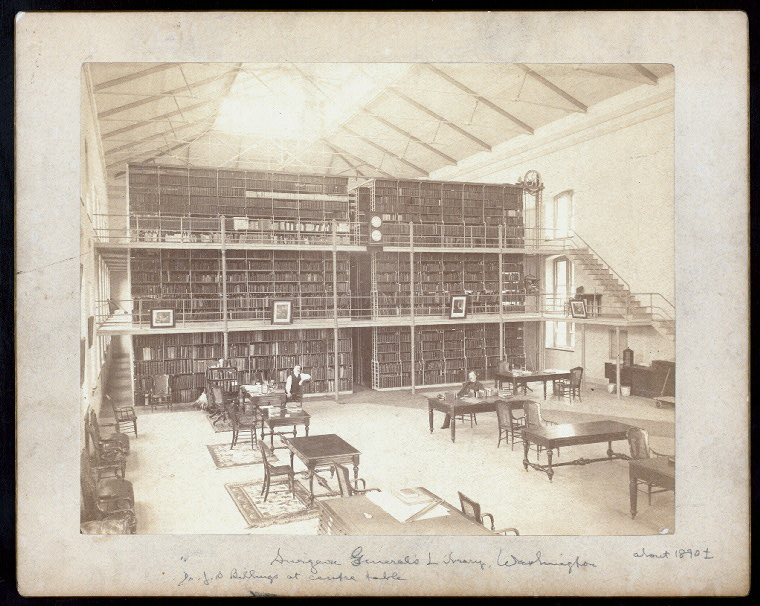

See Part I for biographical information about John Shaw Billings, his experience as a Civil War surgeon, and his innovatory Surgeon-General library’s Index Catalogue.

John Shaw Billings’s hospital designs, which limited the spread of disease, and his education of the public about hygiene are more relevant than ever, considering the CDC’s recent struggle to combat the spread of Ebola and Enterovirus D68. Despite modern technology, educating the public about methods of contagion and effectively quarantining the ill remains an issue. We have, in large part, Billings (of Allensville, Indiana) to thank for many of the basic preventive measures in hospitals, particularly with the establishment of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The Civil War revolutionized the American medical system, as it required personnel to treat large numbers of severely wounded soldiers in rapid fashion. In addition to treatment problems, such as preventing infection, personnel struggled with administrative issues like locating and communicating with medical staff and procuring supplies. Adapting to these obstacles informed medical treatment in the post-war public health sphere, as Billings confirmed in an address:

The war of 1861-1865, and the great influx of immigrants . . . taught us how to build and manage hospitals, so as to greatly lessen the evils which has previously been connected with them, and it also made the great mass of the people familiar with the appearance of, and work in, hospitals, as they had never been before.

His own experience as a Civil War surgeon and his “novel approach” to hospital administration appealed to the trustees of the Johns Hopkins’ fund, tasked with establishing a hospital for the “indigent sick.” After inviting five medical professionals to submit plans for the hospital, they selected Billings’s design in 1876. In their article, A. McGehee Harvey and Susan L. Abrams noted that it “was Billings the man, rather than his proposal” that convinced the trustees to appoint him to the task, as he was extremely knowledgeable about medical education, hygiene, and the “philosophical underpinnings” of hospital construction.

Billings’s essay to the trustees reflected his revolutionary ideas about medical treatment and education, asserting that a hospital should not only treat patients, but educate medical professionals. In that period, requirements to receive one’s medical degree were low and medical education often failed to adequately prepare students to practice medicine. Billings sought to change this by wedding the hospital to the university, providing students with hands-on experience. He also sought to raise standards of medical education, so that a diploma ensured the physician could “learn to think and investigate for himself.”

Under Billings’s design, the Johns Hopkins Hospital opened in 1889 and included a training school for nurses, a pathological laboratory for experimental research, and connected to a building with a teaching amphitheatre. In an address at the opening of the hospital, Billings stated that with the hospital he hoped to produce “investigators as well as practitioners” by having physicians “issue papers and reports giving accounts of advances in, and of new methods of acquiring knowledge, obtained in its wards and laboratories, and that thus all scientific men and all physicians shall share in the benefits of the work actually down within these walls.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital raised the standards of medical education, treatment and sanitation, and was modeled by other hospitals. By 1894, The (Washington D.C.) Evening Star dubbed Billings the “foremost authority in the country in municipal hygiene and medical literature.” In addition to revolutionizing hospital administration and design, Billings was an early advocate of what is referred to today as “bedside manner.” In his 1895 Suggestions to Hospitals and Asylum Visitors, he asked readers to consider

Is a spirit of kindness and gentleness apparent in the place? . . . Is the charitable work of the hospital performed in a charitable way? Do the physicians and nurses display that enthusiasm and esprit due corps which are essential to good hospital work?

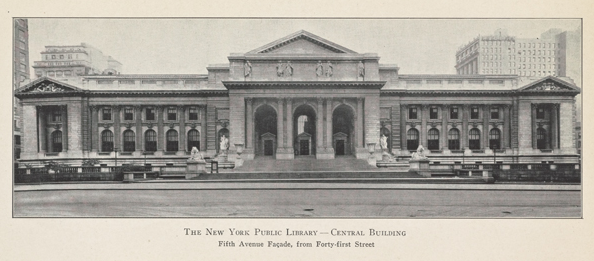

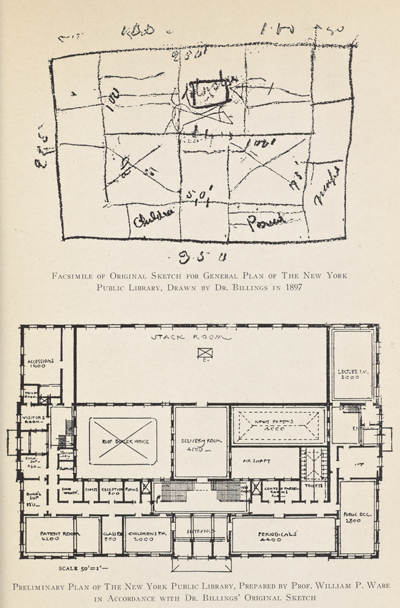

Billings’s accomplishments were not relegated to hospitals. In 1896 Billings served as the first director of the New York Public Library (serving until his death in 1913), expanding its collections “without parallel.” He publicly recognized NYPL female employees and at a Women’s University Club meeting lamented that “most of the library work is done by women, and done splendidly, and it is a shame that they are not better paid.” Industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie solicited Billings’s help with the establishment of a system of branch libraries in New York City and referred to Billings on various educational matters. Additionally, Billings convinced Carnegie to donate millions of dollars to public libraries throughout the United States.

Billings also worked with the U.S. Census from 1880 to 1910 to develop vital statistics. He sought to record census data on cards using a hole punch system, which would allow the data to be counted mechanically. Herman Hollerith applied Billings’s concept, devising “‘electrical counting and integrating machines’” employed by the U.S. Census.

Billings passed away March 11, 1913 and was buried in the Arlington National Cemetery. At a meeting to honor Billings’s life at the Stuart Gallery of the New York Public Library, Andrew Carnegie contended of Billings “by his faithful administration of the great tasks committed to him he left the world better than he found it. I never knew a man of whom I could more safely say that.” The Evening Mail summarized the sentiments of many, including the author of this post, stating

“One gasps at the many lives he has led, the many appointments he has filled, and his gigantic work among libraries and hospitals.”

For more about Billings’s pioneering work, as well as his many other accomplishments, see the corresponding Historical Marker Review and the National Medical Library’s extensive John Shaw Billings Bibliography.

Interested in historic hospitals and medical advancements? Stay tuned for our forthcoming marker about Central State Hospital, an Indianapolis mental health facility that opened in 1848 and built a groundbreaking pathology lab in 1896.