The 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health put the responsibility back on each individual state to determine abortion law for its citizens. In presenting a history of abortion in Indiana, I hope to share how both access and barriers to the termination of pregnancies have changed from the 19th century to the present. Due to the complexities of the abortion debate in Indiana, this article will only discuss the state of abortion prior to the 1970s.

While current laws seeking to ban abortion in Indiana and across the United States focus on the detection of a fetal heartbeat, legal cases between 1812 and 1926 were frequently concerned with “quickening,” which is defined as “the point in which the pregnant woman first feels the fetus move . . . usually between the sixteenth and eighteenth week of pregnancy.”[1] Prior to the point of quickening in a woman’s pregnancy, abortion was not considered a crime since the woman might not have been aware of the pregnancy, particularly if her menstrual cycle was irregular.[2] Instead, these women were often regarded as victims of their own actions in allowing themselves to become pregnant or as victims of an illegal abortion resulting in their death. It is this latter situation, unfortunately, that has allowed historians to learn about the history of abortion practices within the United States. The stories were often only publicly shared through inquest reports, which sought to investigate any deviations from acceptable medical practices that led to death.[3]

In the late 1800s, abortion became a statutory crime in Indiana, as in all states in America. This means that the criminality of the action was written into state laws rather than relying only on the precedent set by court decisions, also called “common law.”[4] The specific statute or law included the elements that an individual must satisfy to be found guilty of the crime, such as the action performed, their mental state when the act was performed, and proximate causation, which is defined as a link between the action and the effect of that action.[5] Despite statues and legal precedent asserting the criminal nature of abortions, women were frequently exempt from liability for their participation in terminating the pregnancy, with most charges instead filed against the individual who performed the abortion.[6]

Although women did not speak openly about abortions outside of their social circles, they did confide in their close friends and family members of their desire to be “fixed up” or to “bring their courses around.”[7] According to many historians’ investigations into the topic, women in the 18th and 19th centuries often turned to abortion as a common means of birth control, with some even asserting that it was safer than childbirth, which claimed the lives of numerous women annually. [8] Women often shared folk remedies or other methods for terminating the pregnancy in much the same way they would have discussed the treatments for other common illnesses.[9]

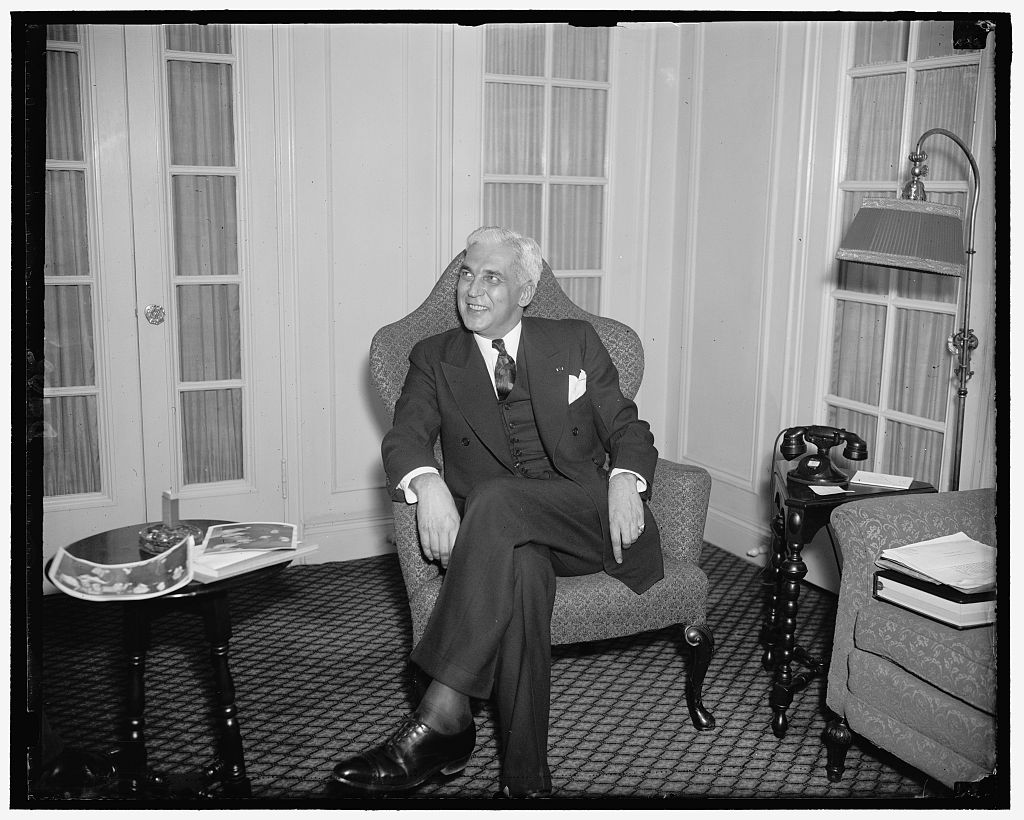

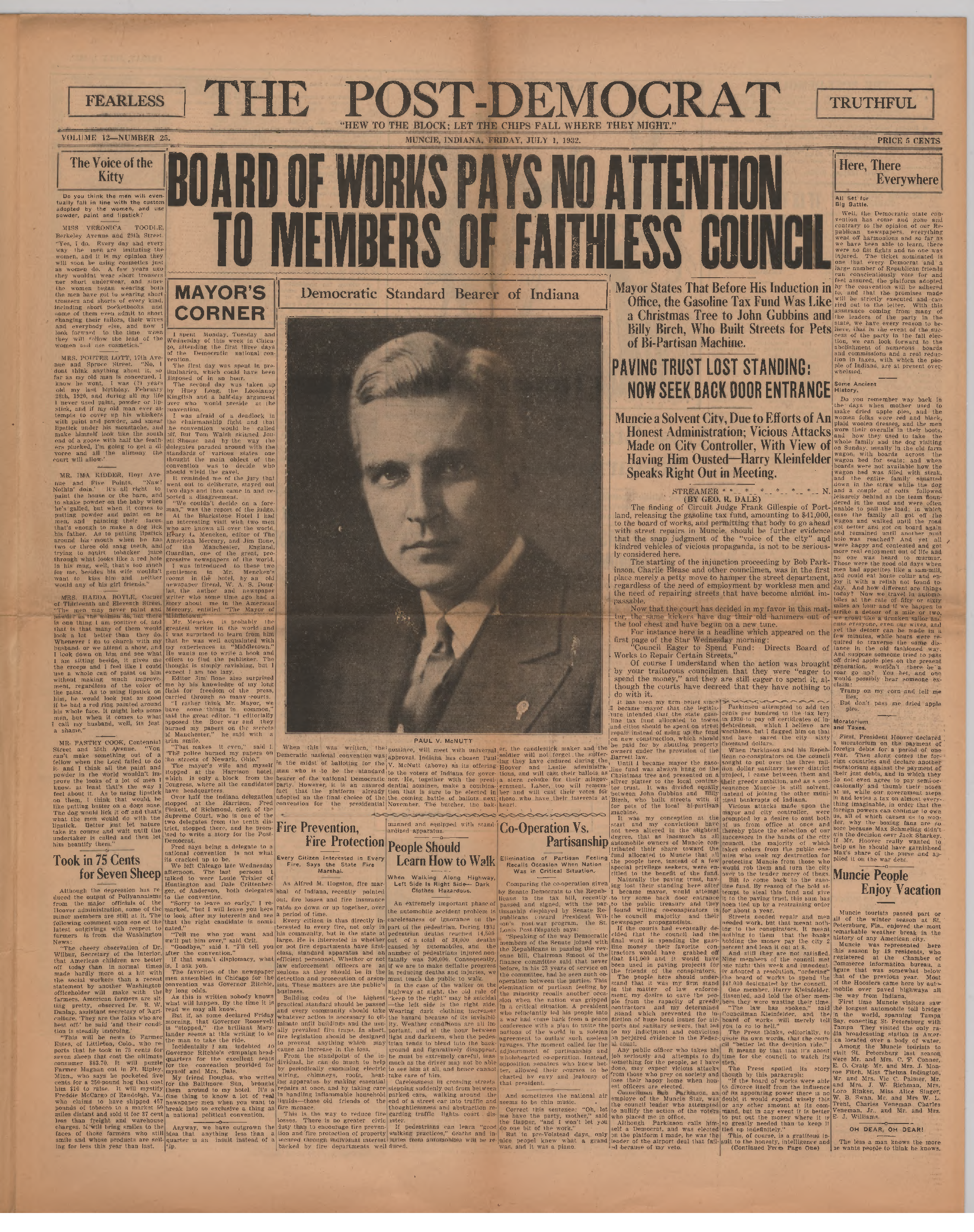

At the turn of the 20th century, approaches to understanding and addressing the rate of abortions within the community involved comparing it with other birth control methods and encouraging the avoidance of pregnancy to prevent the need for an abortion. One such advocate was New York nurse Margaret Sanger,[10] who spearheaded the birth control movement, eventually leading to the approval of modern contraceptives. Sanger reportedly solicited the help of Roberta West Nicholson, a Hoosier legislator (1935-1936) and activist, who co-founded the Indiana Birth Control League in 1932, Indianapolis’s first Planned Parenthood center. A New York representative visited Nicholson in the city, describing the “very, very disappointing lack of progress they seemed to be making because there was apparently very little known about family planning and very little support in general terms for such a concept.” Nicholson was convinced that this should change and established a chapter in Indianapolis. Thus began her 18 years-long work as a family planning and social hygiene advocate.

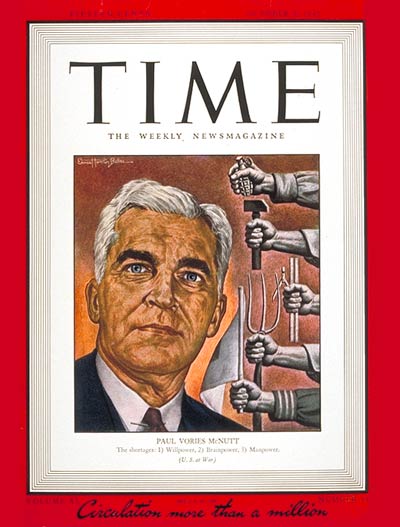

Controversially, Sanger argued in favor of abortion for eugenics, though without the overtly racist undercurrent of most pro-eugenics writings. Instead, her arguments, which often referred to minority and immigrant women indirectly, called for increased access to contraception to assist in limiting the number of children born in their families.[11] At the core of Sanger’s arguments was the idea that “the ability to control family size was crucial to ending the cycle of women’s poverty.”[12] Indiana took Sanger’s beliefs a step further and passed a new law in 1907 that authorized the involuntary sterilization of “confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles, and rapists,” following the argument that poverty, criminal behavior, and mental problems were hereditary.[13] According to the historical marker placed outside the Indiana State Library in 2007 to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the law, approximately 2,500 people within state custody were sterilized under the mandatory sterilization approved by Governor J. Frank Hanly.[14]

In her work with minority, immigrant and working-class communities, Sanger often cared for women who were “relieved if there was a stillbirth, because they could not afford to raise any more children.”[15] As a result, it was these women that Sanger most commonly targeted with her advocacy for increased access to birth control in place of abortions; however, historians like Leslie Reagan and Joan Jacobs Brumberg have argued that abortions were sought by women in all sectors of society to prevent an unwanted birth or to protect a young woman’s reputation. Reagan found that mothers who helped their daughters seek illegal abortions often cited the double standard between males and females in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the mother “knew that bearing an illegitimate child would stigmatize her daughter for life while the boyfriend could experience sexual pleasures without hurting his honor.”[16]

Alternatively, unmarried young women who were kicked out of their homes upon disclosure of their pregnancies were encouraged to bear their children in maternity homes, which often refused to admit Black women.[17] Women who lived in these homes until the birth of the children were required to repent of their sin, perform domestic tasks, participate in religious services, and breastfeed the infants for several months even if they planned to give the children up for adoption.[18] Historians like Regina Kunzel have uncovered evidence that many young women in maternity homes tried and failed to abort their pregnancies as opposed to remaining in the maternity homes.[19]

In the 1930s, particularly during the Great Depression, married Black and white women within similar socioeconomic classes sought abortions at approximately the same rate, often citing their employment or role as the family breadwinner as a critical factor in wishing to avoid another child.[20] Furthermore, data has indicated no significant distinction between abortion rates when classified by religious background; however, the timing of the abortions often differed. Catholic and Jewish women gave birth younger and chose abortion as they aged, whereas Protestant women often sought abortions at younger ages, choosing to give birth later in life.[21]

Throughout the 1920s and 1940s, women from Indiana and other midwestern states often visited downtown Chicago to obtain an abortion at the medical practice of Dr. Josephine Gabler, who had established herself as an expert in the field willing to accept referrals from other medical professionals, despite the practice being illegal in Illinois as well.[22] To protect her identity, that of her staff, and the women visiting the practice, Dr. Gabler and her staff instructed women not to call anyone else if they had issues following their procedure, with the clinic staffing a 24-hour phone line available to assist patients. When women arrived at the clinic, the receptionist, Ada Martin, would lead them back to the room and cover their eyes with a towel so they could not identify the physician performing the procedure prior to putting them to sleep. She would then provide them with instructions for aftercare. Dr. Gabler and her staff paid physicians a percentage of the procedure fees for referring patients to the clinics. The clinic also paid monthly bribes to police officers, which allowed them to continue providing abortions openly without criminal prosecution.[23]

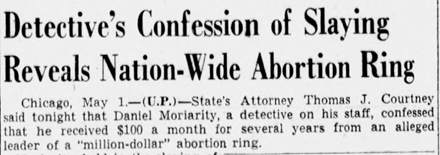

One police officer who received bribes from Gabler’s clinic was Indianapolis Detective Daniel Moriarity. In 1941, the clinic’s former receptionist Ada Martin, who had purchased the clinic from Dr. Gabler, was the victim of an attempted murder. Tragically, Moriarity murdered Dr. Gabler’s daughter, mistaking her for her mother. He was attempting to hide the bribes he had received from Gabler and Martin. His crimes exposed the clinic’s practices for the first time.[24] Despite raids on the office in August 1940 and February 1941, convictions against Martin and her receptionist, Josephine Kuder, were overturned because the evidence used to build the case had been drawn from illegally-seized patient medical records.[25] During the trial, numerous women were forced to take the witness stand, sharing their experiences and subjecting themselves to the scrutiny and stigma of the courts.[26] One woman’s medical record from the clinic was even published in the Chicago Daily Tribune as a “sample,” and other women had their names and photos printed, further exposing them to unwanted attention and questioning outside of the courts.[27]

From the late 1930s into the 1970s, poor white women and Black women in northern Indiana and Detroit began to visit Dr. Edgar Bass Keemer Jr., a Black physician practicing in Detroit. He was urged by his wife, another physician who had obtained an abortion herself while completing her medical training, to perform abortions.[28] Dr. Keemer initially refused to perform an abortion for an unmarried woman, who later died by suicide, leading to his commitment to helping other women to prevent a similar tragedy. Many poor white women regarded Dr. Keemer as a preferable option despite his race and gender because he provided follow-up care and, in the case of the procedure failing, arranged for the woman to have care at a hospital, which he fully paid in addition to any lost wages from missing work.[29]

For women able to make the journey to either Chicago to see Dr. Gabler or Detroit to visit Dr. Keemer, there was often concern about the amount of time a woman would be away from home, leading to the risk of others finding out about her abortion and stigmatizing her for her choices.[30] Abortions at Dr. Gabler’s clinic ranged in price from $35 to $300, with most women paying $50.[31] The cost was higher for abortions performed later in the pregnancy due to the added complexity. This encouraged women to seek treatment as early in the pregnancy as possible to limit costs.[32] Dr. Keemer’s patients were charged $15 in the late 1930s, with fees increasing on a sliding scale to $125 by the 1960s. If the procedure failed, Keemer returned the fee paid and also covered all patient fees associated with the woman receiving a D&C at a local hospital.[33]

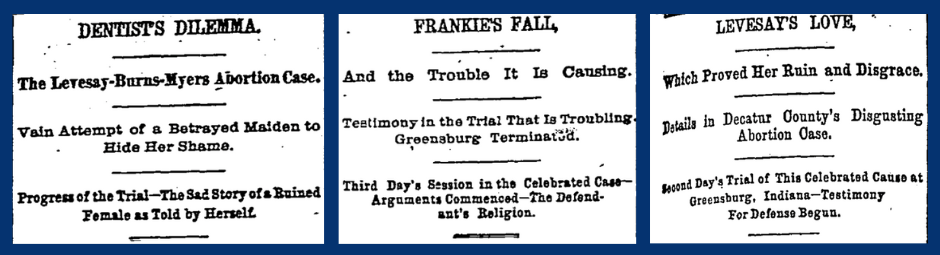

Access to abortions was particularly difficult for women living south of Indianapolis without the opportunity to seek treatment from the Gabler-Martin or Keemer clinics. In this area, some women resorted to procedures performed secretly by other professionals. One such case that gained national attention was that of Eliza Francis Levesay from Decatur County, which is located southeast of Indianapolis.[34] Levesay had had an affair with a young man named William Myers, and she became pregnant. Because Levesay was from a poor family and Myers was from a wealthy family, they believed it was in the best interest of both of their reputations that she seek an abortion.[35] Her abortion was performed by Dr. C. C. Burns, a local dentist. When Levesay became ill and sought medical treatment, her physician reported the case to the state authorities. While an investigation was performed, the jury could not reach a unanimous decision against any of the parties, and the case was dismissed.[36]

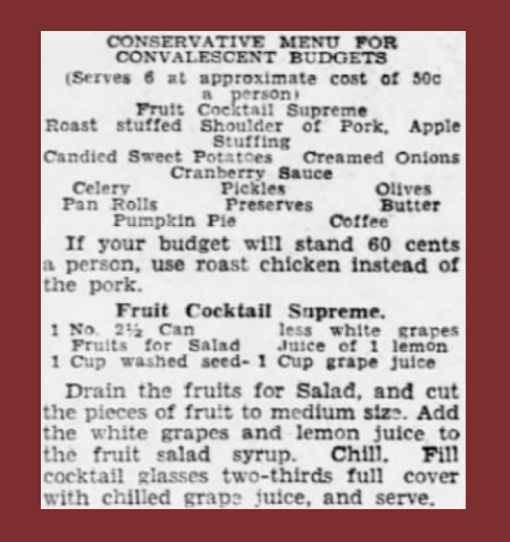

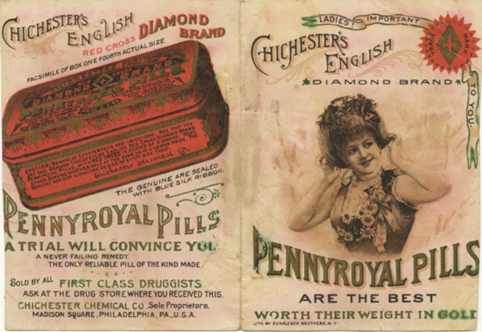

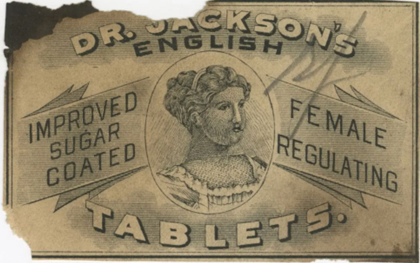

Profiting from abortion restrictions and lack of access to safe clinics, entrepreneurs marketed various pills and remedies that women had shared with each other for free. Women either mixed their own concoctions or purchased various remedies through the mail, with them marketed under various different names to avoid seizure under the Comstock Act, which prohibited the sending of “obscene” or “unlawful” materials through the postal service.[37] Interestingly, such restrictions were often applied only to those packages crossing state lines, urging entrepreneurs to take up the cause within the state as well.[38] Such remedies were not regulated by the FDA; therefore, their safety and efficacy were not established.[39] It is unknown whether such treatments actually worked or how many people died or became ill from using these them. In fact, some state laws, such as those published in 1827 in Illinois, classified the treatments as poisons.[40]

In addition to physical harm resulting from such “treatments,” Dr. Keemer and others worried about women’s mental health should they be refused abortions. Despite state laws, demand for abortion increased in the decades following the Great Depression and World War II as more women entered college and the workplace.[41] Women needed to control when they would become pregnant because “once a woman was visibly pregnant, her school would expel her and her boss fire her . . . In short, pregnancy threatened to destroy a young woman’s life and ambitions.”[42] To protect their reputations and their futures, women from the 1930s to the 1960s sought illegal and unregulated abortions, which were often performed by individuals without medical training. Other women from the 1940 to the 1960s found sympathetic psychiatrists were able to secure abortions for “therapeutic reasons” to help prevent the “emotional distress and suicidal intentions” that women expressed in order to receive referrals for a medical hospital-performed abortion.[43]

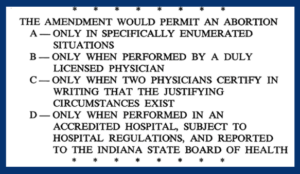

Numerous state and national advocacy groups supported proposed changes to the laws in Indiana. In 1967, Robert Force, an Assistant Professor at Indiana University School of Law in Indianapolis, and Irving Rosenbaum Jr., a physician, drafted the new Indiana Bill (H.B. 1621) and published a statement in which they argued that physicians needed to fully assess a woman’s prognosis if not able to obtain a medical abortion, much as they would when considering treatment for any other medical condition.[44] Additionally, they encouraged the incorporation of protections for women who were victims of crimes, such as rape or incest, and women with mental conditions who could not adequately appreciate their conditions or care for a child after its birth.[45] [46]

Some of the groups lobbying for change and supporting the Indiana Bill represented bipartisan, secular, and religious organizations, including the Indiana Civil Liberties Union, Indiana State Medical Association, American Protestant Hospital Association, Indiana Council of Churches, National Council of Jewish Women, the Indianapolis Star, and other independent advocates.[47] In 1967, these advocacy groups called on legislators to consider legal precedents in which suicidal tendencies had been grounds for granting an abortion in drafting laws that would protect both the mental and physical health of women seeking an abortion.[48] The Indiana Bill passed the House, but the Senate made substantial changes, which essentially removed most of the proposed amendments, which would have made abortion legal without exception, and it was ultimately vetoed by the governor. While abortion was not legal at this point, Indiana had relaxed its anti-abortion laws to protect the mother’s life.[49]

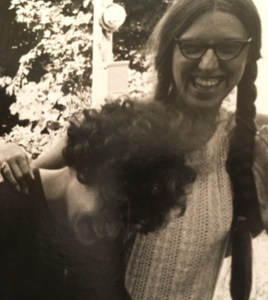

In 1968, the women’s liberation movement reached Bloomington. During weekly meetings of the IU Women’s Caucus, various women shared their challenges with being able to access abortions, which remained illegal.[50] In response to these challenges, including her friend’s horrifying experience in which an abortionist refused to perform the procedure until she had sex with him, Indiana University graduate student Ruth Mahaney started an abortion counseling center, which came to be known as the Midwest Abortion Counseling Service. This center fielded calls from women in surrounding rural areas, students, and women in Bloomington, and offered support from local ministers and doctors who provided counseling services.[51]

The Midwest Abortion Counseling Service center helped connect women to sympathetic providers both in southern Indiana at IU and in the Chicago area through referrals to the Jane Collective for women to receive safe abortions from respectable providers.[52] In an interview as part of the Indiana University Bicentennial Oral History Project, Mahaney recalled driving young women to a municipal airport in Bloomington to be able to get to Chicago as soon as possible for their procedures.[53] After the legalization of abortion under Roe v. Wade in 1973, the Midwest Abortion Counseling Service transitioned to become the Women’s Crisis Service, which not only continued Mahaney’s work in supporting women seeking abortions but also provided support for women in other crises, such as rape or divorce. The center also to connected women to legal resources, daycares, and other available resources.[54]

Force’s and Rosenbaum’s changes to the laws remain present in modern Indiana abortion laws nearly 60 years later. The 2022 Dobbs decision spurred further debates about women’s reproductive rights. The Indiana Legislative Oral History Interview project provides a window into the perspectives of former Indiana lawmakers regarding abortion access.

For a bibliography of sources used in this post, click here.

Notes:

[1] Samuel W. Buell, “Criminal Abortion Revisited,” New York University Law Review 66, (1991): 1780.

[2] Buell, 1782; Julie Conger, “Abortion: The Five-Year Revolution and its Impact,” Ecology Law Quarterly 3, no. 2 (1973): 312.

[3] Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 22.; Buell, 1782.

[4] “Criminal Law,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, accessed May 7, 2023, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/criminal_law.

[5] “Criminal Law.”

[6] Buell, 1783.

[7] Reagan, 23.

[8] Tamara Dean, “Safer Than Childbirth: Abortion in the 19th Century Was Widely Accepted as a Means of Avoiding the Risks of Pregnancy,” The American Scholar, 97; Reagan, 22.

[9] Reagan, 26.

[10] Debra Michals, “Margaret Sanger (1879-1966),” National Women’s History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/margaret-sanger

[11] Melissa Murray, “Abortion, Sterilization, and the Universe of Reproductive Rights,” William & Mary Law Review 63, no. 5 (2022): 1607.

[12] Debra Michals, “Margaret Sanger (1879-1966),” National Women’s History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/margaret-sanger

[13] “Project Overview,” Indiana Eugenics History & Legacy 1907-2007, accessed June 28, 2023, https://eugenics.iupui.edu/ ; “1907 Indiana Eugenics Law,” Indiana Historical Bureau, accessed June 28, 2023, https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/1907-indiana-eugenics-law/.

[14] “1907 Indiana Eugenics Law,” Indiana Historical Bureau.

[15] Ingrid Mundt, “Margaret Sanger, Taking a Stand for Birth Control,” History Teacher 51, no. 1 (2017): 124.

[16] Regan, 28.

[17] Regan, 28.

[18] Reagan, 28-9.

[19] Regina Kunzel, Fallen Women, Problem Girls: Unmarried Mothers and the Professionalization of Social Work, 1890-1945 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993): 68-69, 81.

[20] Reagan, 135.

[21] Reagan, 137.

[22] Reagan, 149.

[23] Reagan, 155.

[24] Reagan, 155.

[25] Reagan, 311. Mrs. Martin estimated in court testimony that she worked as a receptionist for Dr. Gabler for approximately 12-15 years. She purchased the practice from Dr. Gabler in January 1940 and later hired physicians, including Dr. Henry James Millstone, to perform abortions in the clinic. While under indictment following the raids, Dr. Millstone died by suicide from drinking poison on April 17, 1941, with his wife dying by suicide from drinking ammonia shortly after on May 1.

[26] Reagan, 167-168.

[27] Reagan, 167.

[28] Reagan, 156.

[29] Reagan, 157-158.

[30] Regan, 151. Dr. Gabler used surgical techniques for the abortion, including general anesthesia and dilation and curettage (D&C) similar to the procedure following a miscarriage, with after-instructions provided similar to those for women who had just given birth, such as avoiding hot baths or avoiding intercourse while they healed.

In contrast to Dr. Gabler, Dr. Keemer used the Leunbach method, which was reported to be safer and less painful.[30] The process utilized a compounded paste and potassium soap solution inserted into the uterus via a syringe. The vagina was then packed with a sterile gauze tampon, which would be removed 18 hours later at home. Women receiving an abortion via the Leunbach method, on average, spent only 10 minutes on the doctor’s table and reported minimal cramps, with aspirin prescribed to blunt the pain. Women could return home the same day, and a nurse would visit women at home the following day. Dr. Keemer also arranged a follow-up visit as well to ensure all of the contents had been properly expelled to prevent infection.

[31] Reagan, 154-155.

[32] Reagan, 155.

[33] Regan, 157-158.

[34] Madeleine Boesche, “19th Century Anti-Abortion Laws Enforcement in the Rural United States,” Vassar College Clark Fellowship, accessed May 7, 2023, https://www.vassar.edu/history/clark-fellowship/2012/anti-abortion-laws-enforcement-rural-united-states.

[35] Various sources utilize different spellings for Mr. Myers’ last name, with “Myers” utilized in newspapers covering the case and “Miers” as the spelling in the Boesche article detailing her research into the case.

[36] Boesche, https://www.vassar.edu/history/clark-fellowship/2012/anti-abortion-laws-enforcement-rural-united-states.

[37] Reagan, 13.

[38] Melody Rose, Abortion: A Documentary and Reference Guide (London: Greenwood Press, 2008): 31.

[39] Sarah Gordon, “Female Remedies: A Little Show Draws a Big Response,” New York Historical Society Museum & Library, June 10, 2019, https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/female-remedies-a-little-show-draws-a-big-response.

[40] Reagan, 10.

[41] Reagan, 194.

[42] Reagan, 194-5.

[43] Reagan, 202.

[44] Robert Force, “Legal Problems of Abortion Law Reform,” Administrative Law Review 19, no. 4 (1967): 370-372.

[45] Force, 372.

[46] Force, 372.

[47] Force, 365.

[48] Force, 365.

[49] Force, 365.

[50] Mary Ann Wynkoop, Dissent in the Heartland: The Sixties at Indiana University (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002): 136.

[51] Julia Kilgore, “Ruth Mahaney & Nancy Brand: Insight into IU’s History of Women’s Reproductive Rights,” IUB Archives (blog), October 28, 2016, https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/iubarchives/2016/10/28/ruth-mahaney-nancy-brand-insight-into-ius-history-of-womens-reproductive-rights/.

[52] Madison Stacey, “’It was hidden, you had to hunt’ | How covert networks helped women access abortions before Roe v. Wade,” WTHR.com, last modified August 24, 2022, https://www.wthr.com/article/features/how-covert-networks-helped-women-access-abortions-before-roe-v-wade/531-8839cfb4-8eff-475f-bd6a-27643eea675b.

[53] Stacey.

[54] Kilgore.