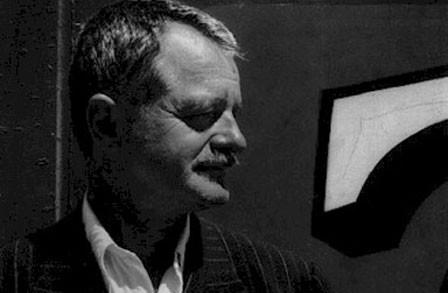

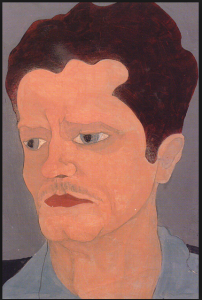

At times described as cantankerous, paranoid, and bitter, Kenneth Rexroth, the trail-blazing Hoosier poet, cajoled and harangued some of the best poets of the Beat Generation. At the same time, he worked tirelessly to promote their work. Rexroth’s own radical poetry both preceded and inspired the Beats, though at times he refused to be associated with the movement that he thought had lost its meaning by the late 1950s, and especially that “hipster” Jack Kerouac.

As important as Rexroth’s poetry is to American literature, his life story is perhaps even more fascinating. And while much has been written about his years in San Francisco laying the groundwork for a literary renaissance in that city that grew into the larger Beat movement, little has been written about his time in Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio – a period when the budding poet rubbed elbows with anarchists, burlesque dancers, criminals, and the artistic and literary elite of the Midwest and the world.

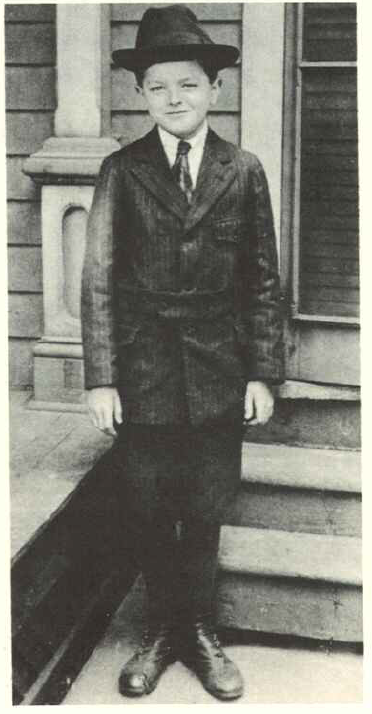

Kenneth Rexroth was born on December 22, 1905 in South Bend, Indiana. Young Rexroth’s first residence was a house at 828 Park Avenue in South Bend which still stands and will soon be the site of an Indiana State Historical Marker commemorating his life and career. In Kenneth Rexroth: An Autobiographical Novel, he described the house as “substantial and comfortable,” near to the Oliver Hotel and Mr. Eliel’s drug store. According to a 1905 article in the Elkhart Daily Review, Rexroth’s father was working as a traveling pharmaceutical salesman.

In 1908, the Rexroth family moved to a home on East Beardsley Avenue in Elkhart, Indiana, a relocation that made the local newspaper.

Rexroth wrote a description of the Elkhart home as well:

This was a quiet residential street above the river where all the best homes in the town were in those days, where the patent-medicine people, the musical-instrument people, the buggy-works people, the corset people, and all the other leading citizens of the town lived in their wooden, sometimes Palladian or Romanesque mansions, and we had our own little Palladian house.

While Rexroth was born into a comfortable life, his family’s circumstances soon deteriorated. His parents, Charles Marion and Delia Rexroth, had difficulties with alcohol, chronic illness, and each other. Rexroth wrote that his mother was drinking champagne when she went into labor and bluntly called his father a “drunk” and a “constant gambler.” When he was five, circa 1910, they left the lovely house on East Beardsley due to his father’s diminishing finances. The family moved more often then, mostly renting, but Rexroth remembers living in a “run-down Victorian house” on Second Street that he believed they owned. Despite setbacks, he remembered his childhood in Elkhart fondly. His mother taught him to read early and immersed him in classical literature. He spent time at the library, learned French, explored the neighborhood, and fell in love with Helen, “the little girl next door,” when they were just six or seven. His parents were able to afford a family tour of Europe, which made quite an impression on young Rexroth.

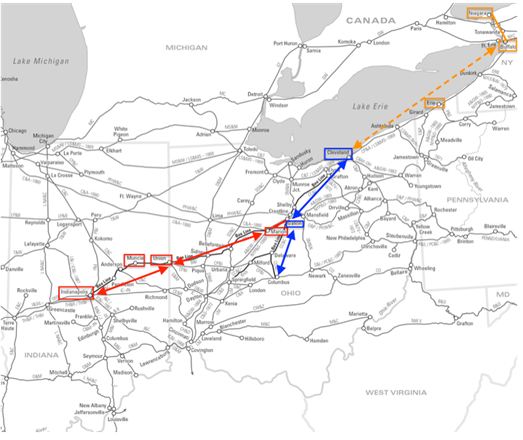

However, his mother continued to succumb to a chronic illness that multiple doctors were unable to diagnose, and his father intensified his drinking and gambling. Sometime around 1914, when Rexroth was nine, the family moved briefly to Battle Creek, Michigan, and then to Chicago the following year, where they lived with relatives. Rexroth’s father’s alcoholism put him near death on at least one occasion and he left the family, likely for some sort of sanitarium. Rexroth moved with his mother into a small apartment and they rarely saw his father. After a painful period fighting what was likely tuberculosis, Delia Rexroth died in 1916. Eleven-year-old Rexroth went to live with his father and grandmother in Toledo, Ohio. Here, Rexroth began to seek and find trouble.

Rexroth had little supervision in Toledo. He began running around town with a gang of boys who would rob cash registers and, despite his young age, he ran various money-making hustles that involved running errands for “brothels, cardrooms, and burlesque shows.” He also witnessed the Willys-Overland labor strike that turned riotous. Rexroth wrote that this was a significant moment in his youth and he “started off in the labor movement.” In 1919, at this uncertain juncture in Rexroth’s early adolescence, his father also died.

Rexroth’s aunt, Minnie Monaham, retrieved the thirteen-year-old trouble maker and brought him back to Chicago to live with the rest of the Monahams. The 1920 U.S. Census shows that the nine person household was located on Indiana Avenue, but they soon moved to an apartment on South Michigan Avenue in the Englewood neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. Rexroth enrolled in the nearby Englewood High School. School administrators quickly expelled him for his poor attitude and attendance. It was outside of the Chicago public school system, however, that Rexroth pursued a more profound education.

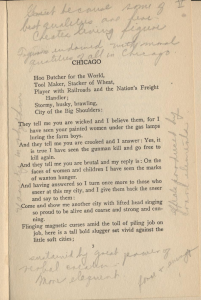

Perhaps in the same manner he was able to gain access to the burlesque theaters of Toledo, Rexroth found access to the clubs of the poets and writers gathered in this Midwest city during the second wave of the Chicago Literary Renaissance. Among these were important local poets such as Carl Sandburg and Harriet Monroe, writers and intellectuals such as Hoosier-born Theodore Dreiser, and political thinkers such as famous Hoosier socialist, Eugene Debs, as well as the “big names” of the international art and literature worlds. This intellectual elite met at formal and informal clubs and locations around the city.

Rexroth also explored the radical political movements of the period at venues such as the Washington Park Bug Club, also known as Bughouse Square, which met in a “a shallow grassy amphitheater beside a lagoon off in the middle of the park,” according to Rexroth. Bughouse Square was, for a time, “the most celebrated outdoor free-speech center in the nation and a popular Chicago tourist attraction,” according to the Chicago Historical Society. Here, people with a host of different ideas would get on their soapboxes (sometimes literally) and orate to the crowds that would gather. Rexroth wrote that “here, every night until midnight could be heard passionate exponents of every variety of human lunacy” such as:

“Anarchist-Single-Taxers, British-Israelites [or Anglo-Israelite], sell-anointed archbishops of the American Catholic Church, Druids, Anthroposophists, mad geologists who had proven the world was flat or that the surface of the earth was the inside of a hollow sphere, and people who were in communication with the inhabitants of Mars, Atlantis, and Tibet, severally and sometimes simultaneously. Besides, struggling for a hearing was the whole body of orthodox heterodoxy — Socialists, communists (still with a small “c”), IWWs [International Workers of the World], De Leonites, Anarchists, Single Taxers (separately, not in contradictory combination), Catholic Guild Socialists, Schopenhauerians, Nietzscheans — of whom there were quite a few — Stirnerites, and what later were to be called Fascists.”

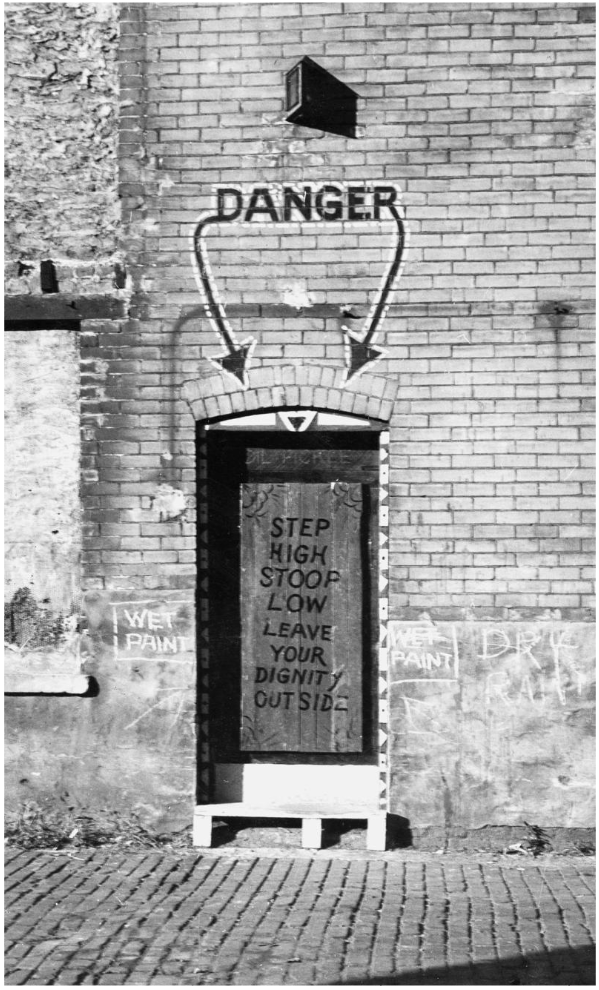

Another inspiring haunt for Rexroth was the Dill Pickle Club, not far from Bughouse Square, where artists and writers along with socialists and anarchists gathered for social and artistic experimentation. Rexroth wrote that there were independent theater productions Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. On Sunday night, there were lectures on various topics. On Saturday nights “the chairs were cleared away and the Chicago jazzmen of the early Twenties played for a dance which lasted all night.” Rexroth remembered the actors and sets as being awful but somehow they produced plays that were “the very best.” Lectures were given by “every important scholar who came through the town, and all those who were attached to the universities.”

Most significantly, however, Rexroth gained entrée to the salon at the home of Jake Loeb, where he encountered the leaders of the local literary movement, international visitors such as D. H. Lawrence, and access to books of artists and writers who would greatly influence him, such as Gertrude Stein. In his autobiography, Rexroth referred to Loeb’s home as “a more important Middle Western cultural institution in 1923 than the University of Chicago, the Art Institute, the Symphony, and the Chicago Tribune put together.” He wrote that he met “everybody who was anybody in the Chicago of the Twenties and everybody who was anybody who was passing through town.” He continued:

“Besides the famous transients, many of whom stayed in the place, the house was full every night of the cream of Chicago’s intellectuals in the brief postwar period of Chicago’s second renaissance. It seems rather pointless even to list them — any of them — because they were all there. . . It is not that I met famous people — it is that I learned by listening to impassioned discussion among mature people, all of whom were out in the world putting their ideas into effect.”

Rexroth was also starting to put his ideas into effect. Although he had shown little academic or literary promise thus far, Rexroth became “a prolific painter and poet by age seventeen,” according to the Poetry Foundation. By this point he was running from one cultural hot-spot to another, performing the poetry to which he was being exposed. He wrote in his autobiography that if he hustled he could make over fifty dollars in a weekend. He continued, “Thus began my career as a boy soapboxer, bringing poetry to the masses.”

He began working a number of odd jobs, and in his free time, experimenting with oil paints and piano. One such job was at the Green Mask on Grand Avenue and State Street. Rexroth referred to the Green Mask as a “tearoom,” but it was probably more accurately a cabaret, and it was located in the basement of a brothel. Rexroth wrote, “The place was a hangout for bona-fide artists, writers, musicians, and people from show business.” He continued, “In the Mask there gradually formed a small, permanent family of oddities who were there every night and never paid for their coffee.” Here Rexroth was able to see and perform poetry with some of the era’s best poets and musicians, both black and white, local and national. These included the “seclusive and asocial” poet Edgar Lee Masters, local African American poet Fenton Johnson, nationally-acclaimed black poet and playwright Langston Hughes, the local jazz drummer Dave Tough (who Rexroth called Dick Rough in his autobiography), and an assortment of dancers, singers, and drag queens. This group held weekly poetry readings and lectures and jazz performances. Rexroth and others began combining jazz and poetry, a technique he would become known for by the time he headed out west and one that would greatly influence the Beat Generation. He wrote that here, at the Green Mask, “happened the first reading of poetry to jazz that I know of.” About this early Chicago jazz scene, he wrote:

“I’m afraid that I can’t provide any inside information about the formative years of jazz, for the simple reason that none of us knew that this was what was happening. We didn’t know we were making history and we didn’t think we were important. . . Jazz was pretty hot and made a lot of noise. People talked loud to be heard above it, got thirsty and drank too much and made trouble, so we tried to keep the jazz small and cool . . . I remember many nights going over to the piano and saying, ‘For Christ’s sake, cool it or you’ll get us all busted!'”

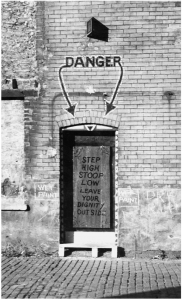

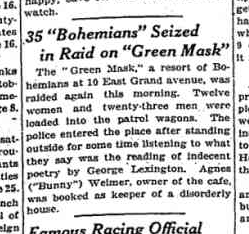

As he predicted, the Green Mask did get busted. In 1923, the Chicago Tribune reported that thirty-five “Bohemians” were arrested in a raid at the Green Mask. The Tribune article stated: “The police entered the place after standing outside for some time listening to what they say was the reading of indecent poetry by George Lexington.” The owner was booked as “keeper of a disorderly house.” Rexroth was also arrested because he was considered part owner for investing some small amount of money into the place. He was sentenced to a year in jail.

He described the conditions on his arrival to the Chicago House of Corrections, or the “Bandhouse” as it was called:

This was quite a place. It had been built back in the Seventies or Eighties, with long, narrow windows like the archers’ slots in medieval castles, and a warped and muddy stone floor where the water oozed up in winter between the paving blocks. This was the only running water in the place. Each cell was given a one-gallon pail of water once a day and provided with a battered old bucket for a privy. It was a cage-type cell house. The cells were all in the center about thirty feet away from the walls, so the only view was through the heavy iron grilles and door which looked out on brick walls and filthy windows through which it was impossible to see anything. The inner cells looked out on the tier opposite. The whole thing was built of iron, and any movement in it resounded as though it had happened inside a bell; any cough or groan or cry was magnified as if by an immense megaphone. In each cell there were four iron-slatted bunks that folded up against the wall. There were no mattresses, and each fish [inmate] was provided, along with his slops, with a filthy khaki Army blanket full of holes.

Rexroth spent the winter in these circumstances and explained that he “got a little closer to the underworld.” When he got out of the Bandhouse, he spent most of his time pursuing various young women, two of whom lived in the same building, and writing them poetry. He became more involved in local theater productions and continued pursuing radical social theories and chasing down works of avant-garde literature. He began reading more spiritual works and even spent a few months in a monastery. He also began a period of traveling and recording his observations of nature in his poetry – something else he would become known as a master of in later life.

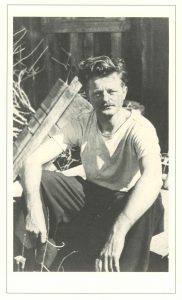

In late December 1926, Rexroth met the artist Andrée Schafer through friends, just briefly outside their door. When his friends asked him what he thought about her, Rexroth replied, “I intend to marry her.” They began working on paintings together, both of them working on the same canvas, “like one person,” according to Rexroth. They married a few weeks later in January 1927 and left for a new life on the West Coast that spring. In San Francisco, instead of experiencing a cultural Renaissance, Rexroth would create one.

Check back next week for more about this Hoosier rebel in part two of this story: Kenneth Rexroth: Poet, Pacifist, Radical, and Reluctant Father of the Beat Generation

For more information:

Kenneth Rexroth, An Autobiographical Novel (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1966).

Linda Hamalian, A Life of Kenneth Rexroth (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991).