This is Part Three of a three-part series on the University of Notre Dame’s opposition to the Ku Klux Klan. See Part One for information on the May 1924 riot and Part Two for more about the integrity modeled by the Fighting Irish during the 1924 regular football season.

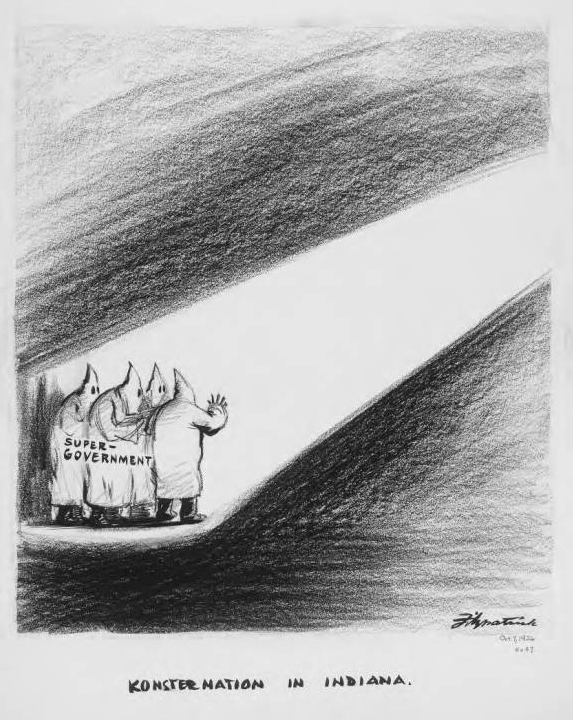

Indiana’s Ku Klux Klan had a good year in 1924. Its members’ lobbying paid off and their xenophobia was codified into law with the Immigration Act of 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act). The act established a strict quota system that unfairly targeted immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, in large part because many immigrants from these areas were Catholics. The Klan and other xenophobes charged that Catholic immigrants would always be loyal to the Pope and to Rome, as opposed to the laws of their adopted country, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary. The new immigration law would keep out these “undesirable” immigrants. For many xenophobes, including Klan members, this was not enough. The Indiana Klan worked to further block Catholics and immigrants from gaining political power and influence. They did so by working to portray immigrants, Catholics, and Jews as “other,” as alien, as unassimilable, as un-American.[1]

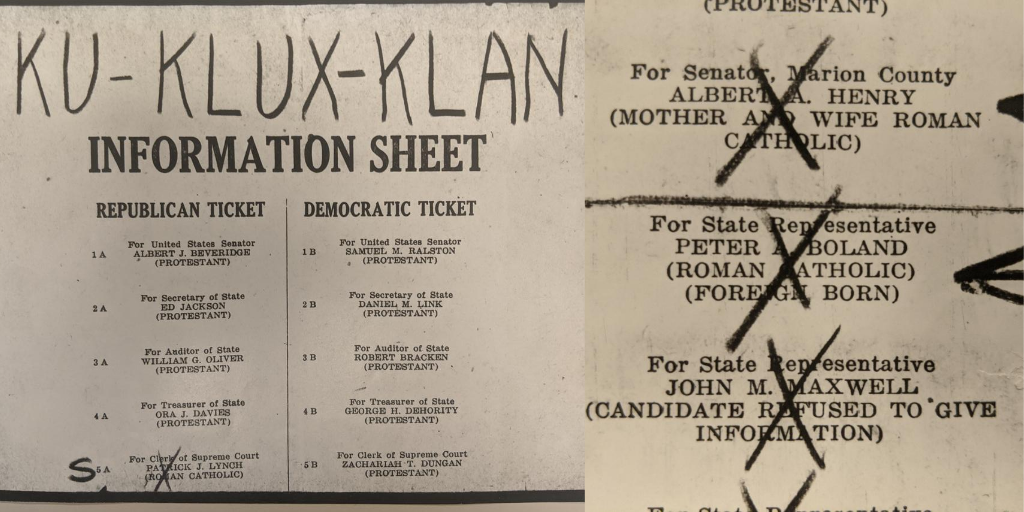

In Indiana, the Klan circulated “Information Sheets” before elections. These were copies of ballots where the Klan noted candidates who were “Negro” or “Foreign Born,” those who were Catholic or had Catholic family members, and those who refused to respond to inquiries.[2] The Klan newspaper, the Fiery Cross, accused Catholics and immigrants of various wild plots against their fellow Hoosiers and positioned Klan members as the innocent victims of attacks by Catholics. The propaganda mouthpiece dedicated full pages to this “mounting list of Roman Catholic offenses,” which supposedly included such “papist crimes” as “arson, theft, assault and battery, murder, slander, intimidation, breach of contract, disrespect for flag and violation of the immigration law.”[3]

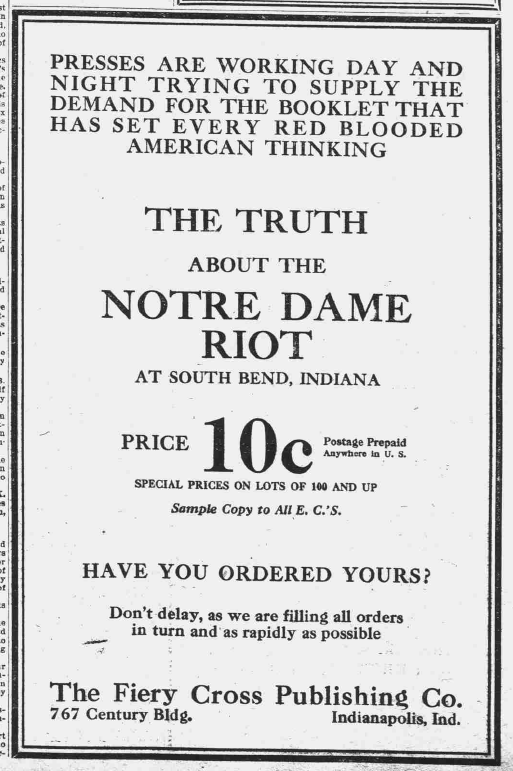

The Klan also continued to use the May 1924 incident at South Bend to vilify the city’s immigrant population as “hoodlums” and Notre Dame University as a front for secret, un-American, “papist” activities that would undermine the values of good Protestant Hoosiers. The Fiery Cross distributed a booklet, “The Truth About the Notre Dame Riot” and ran articles and anonymous letters it claimed were penned by neutral, non-Klan member observers of the “foreign rioting”of May. [4] In truth, these “letters” were racist, anti-Catholic propaganda. These strikingly similar letters, signed with pseudonyms like “An American Citizen” and “Observer” referred to Notre Dame students as”anti-American” and “gangsters. [5] The writers claimed that the students were armed with guns and knives, outnumbered Klan members thirty-to-one, beat women unconscious, tore up the American flag, and spilled the blood of all-American Klansmen, “the same true blood shed at Bunker Hill and Argonne.”[6] While local non-Klan affiliated newspapers reported no such level of violence, no weapons, no women present, and no destruction of the flag, the Klan’s version of events was repeated in mainstream newspapers, tarnishing the university’s reputation.

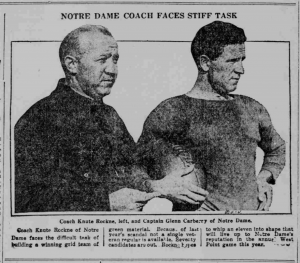

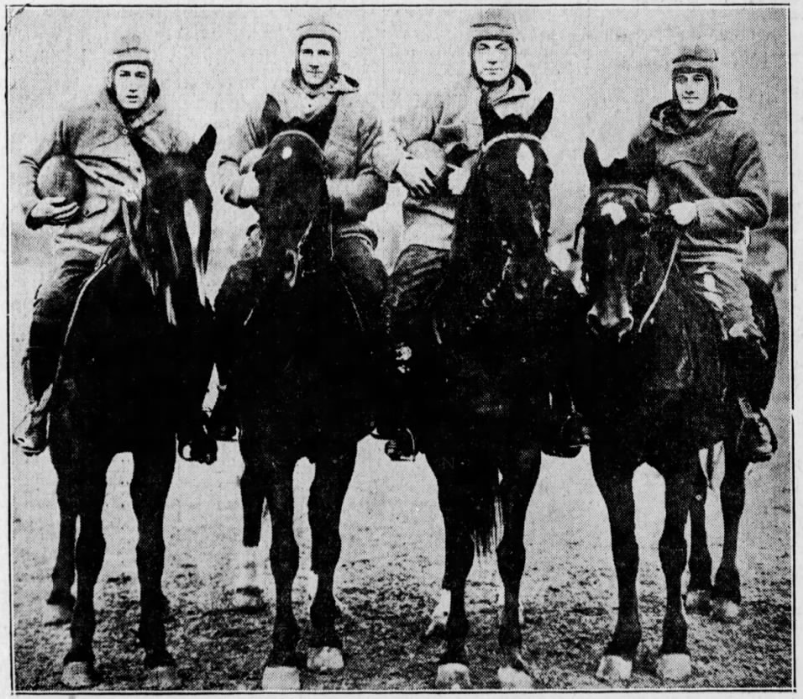

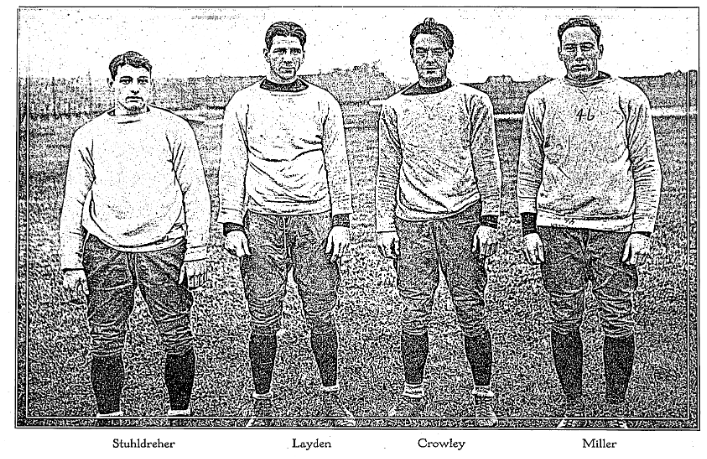

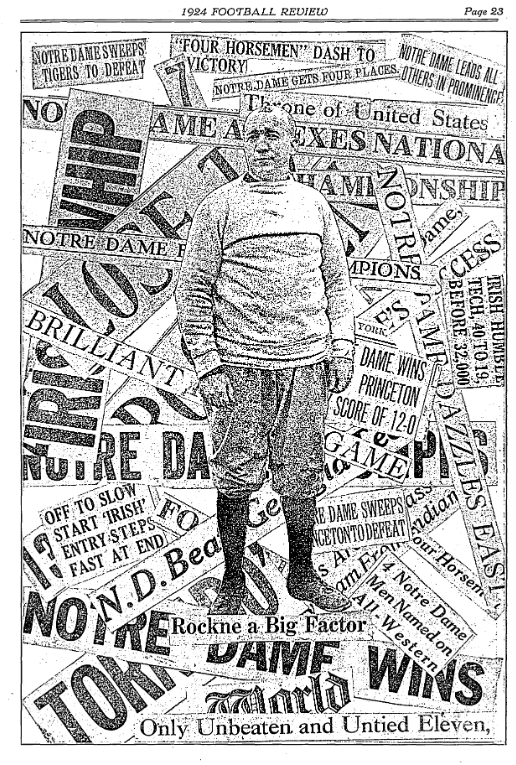

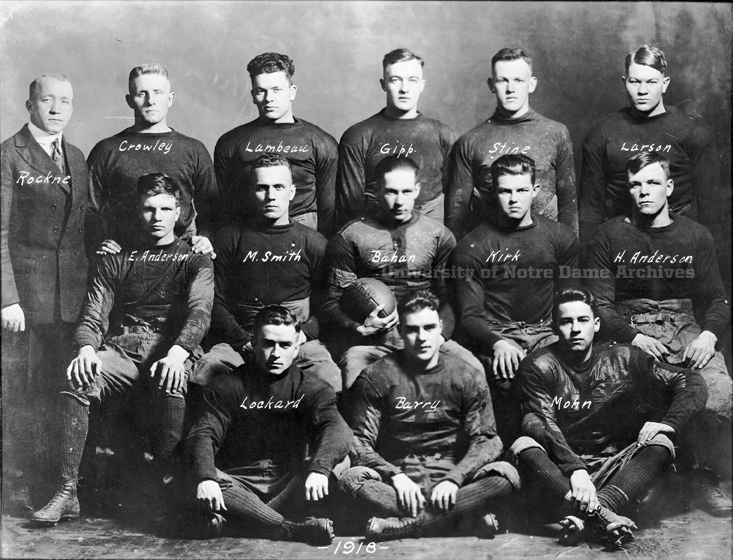

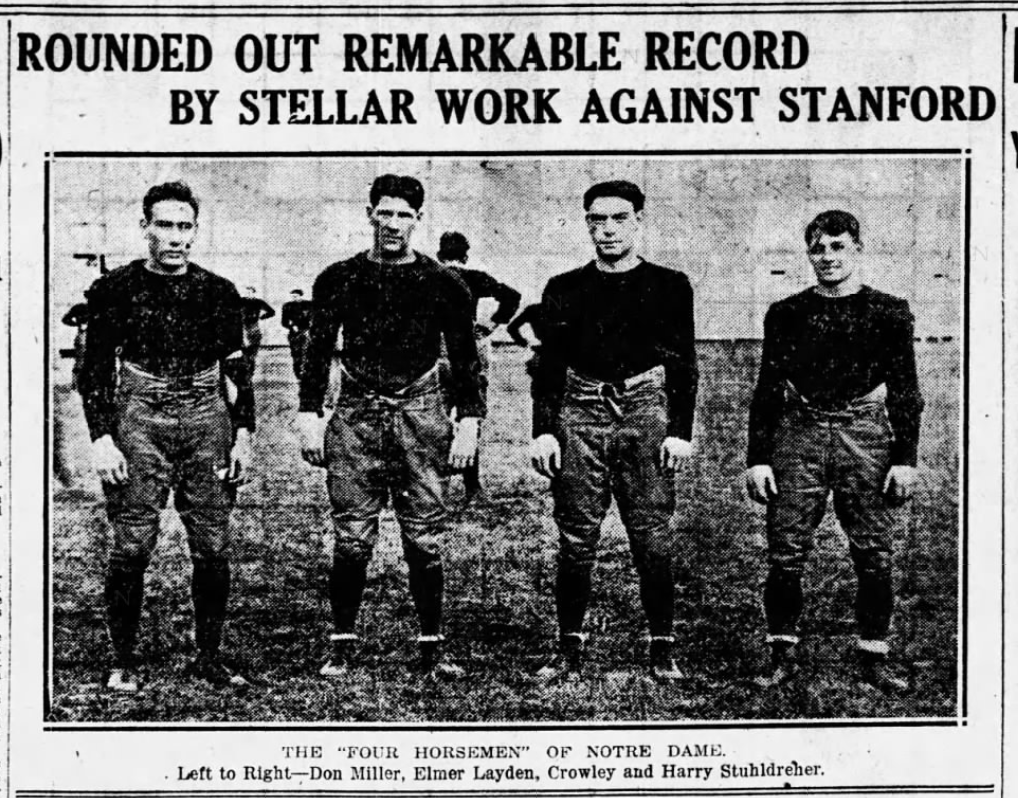

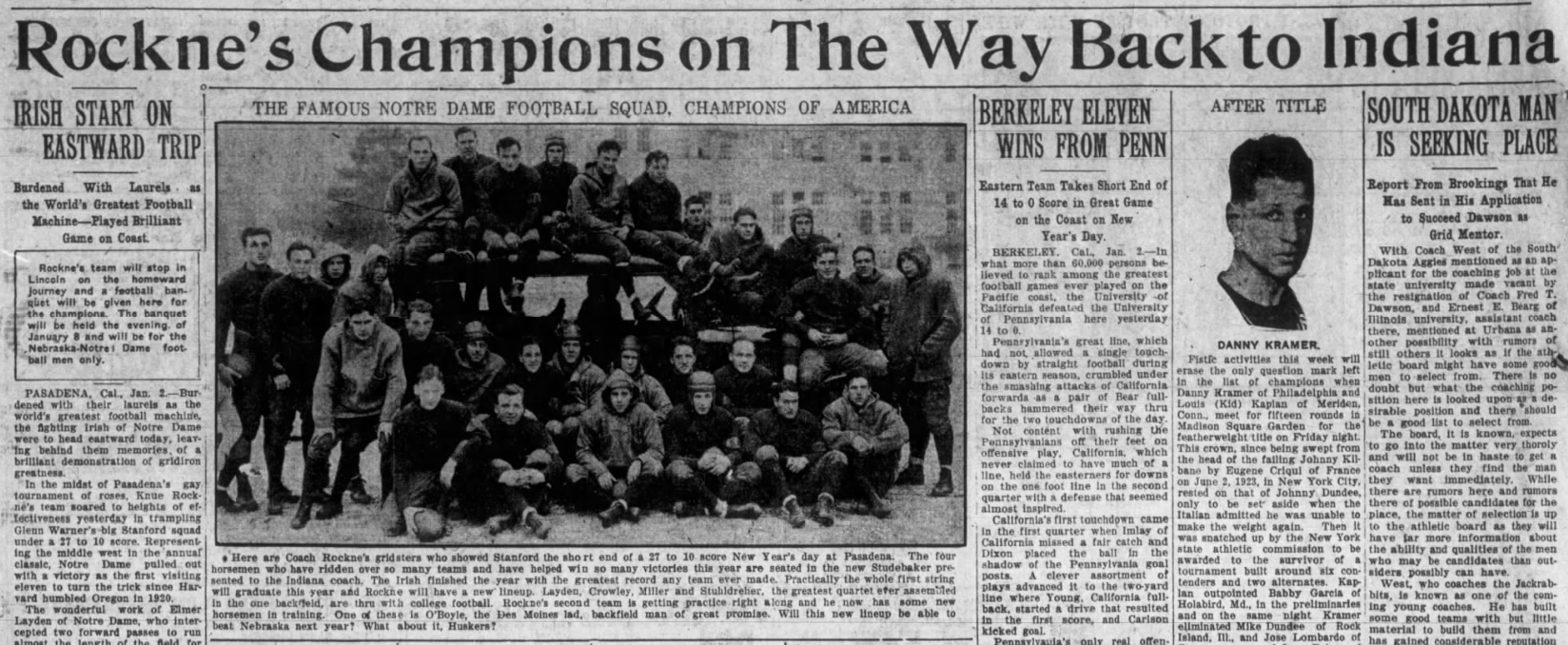

Notre Dame officials knew that the Klan wanted them to react. The Klan had baited students into conflict in May and had been thriving off the propaganda opportunity ever since. The xenophobic group continued threatening to return to South Bend, even holding large rallies on the edge of town. Instead of responding to the Klan, the university worked to counter the damage done to their reputation by promoting its increasingly-popular football team. By winning games, growing its fan base, publicizing its players as wholesome American boys, and linking the school’s Catholicism with its success on the field, Notre Dame flipped the script on the Klan. Newspapers across the country were now talking about Coach Rockne’s brilliant plays, the unstoppable Four Horseman offensive backfield, the Fighting Irish’s undefeated regular season, and the team’s odds at the upcoming Rose Bowl.[7]

The trip to the Rose Bowl presented university leadership with a unique opportunity—a national stage on which to demonstrate that Notre Dame was both proudly Irish Catholic and thoroughly American. Many players were sons of immigrants, improving themselves through education and hard work to achieve success and the American dream. And what could be more American than football? Positive press coverage generated by the Fighting Irish’s undefeated 1924 season convinced President Walsh that mobilizing the full power of the university behind the football team was a winning promotional strategy. According to Notre Dame historian Robert Burns:

When reporters wrote about Rockne’s success or the exploits of the Four Horsemen, they could not do so without also writing about the special religious and academic environment that had made such success and exploits possible. That sort of reporting…was good for Note Dame, for Catholic higher education, and for American Catholics generally in the bigoted climate of 1924. [8]

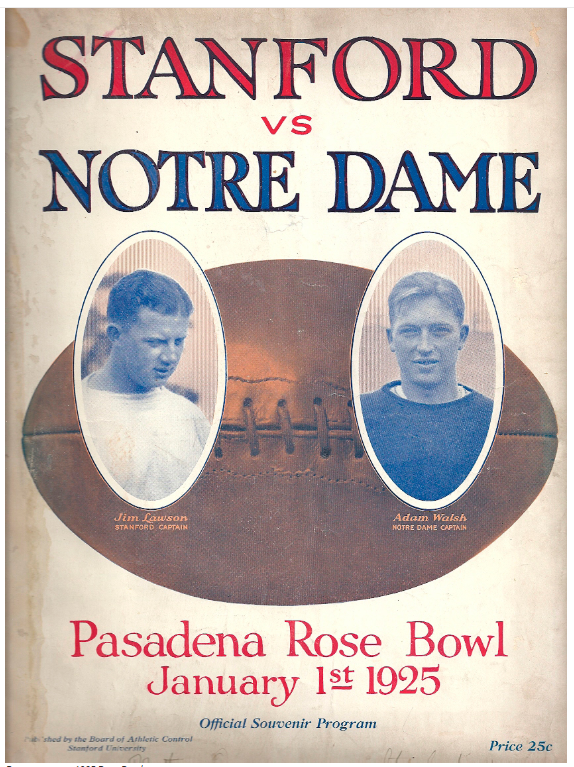

Walsh gave his blessing to the January 1925 match up between Notre Dame and Stanford at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. He then handed over the reigns to Father O’Hara, the school’s “prefect of religion and unofficial keeper of the institutional conscience.” Father O’Hara turned the train trip to Pasadena into a “public relations spectacular.”[9]

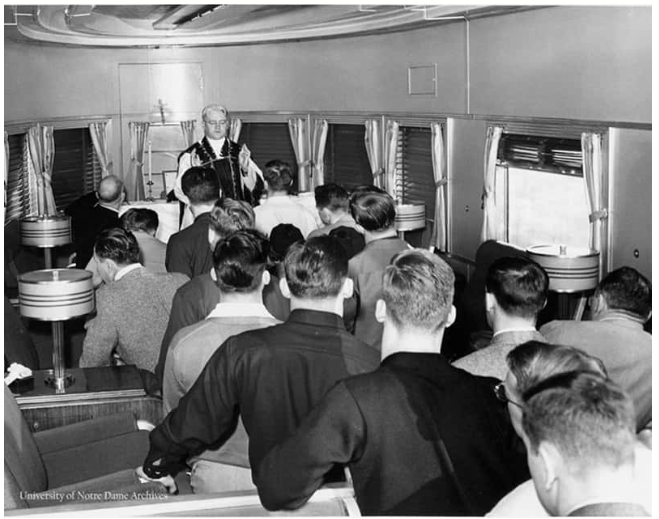

Father O’Hara planned a three week trip centered around the Rose Bowl game and mobilized Notre Dame alumni and Catholic organizations to set up public events en route. Alumnus and railroad executive Angus D. McDonald arranged for a special train to transport the team, coaches, managers, alumni, and Father O’Hara. The train included a chapel car for Mass, Holy Communion, and confession. Father O’Hara believed that the devoutness demonstrated through daily communion, combined with “the gentlemanly conduct of the team” would win over the American public “while bigotry and prejudice received an abrupt setback.”[10]

On Thursday, December 18, 1924, Rockne drilled his players “on a field covered with ice and in a slow drizzle,” a public display of a steadfast team determined to win in January.[11] The next day, the special Notre Dame train left for Chicago. The Tennessean reported that “Hundreds of students and townspeople braved zero degree weather” to see them off.[12] When they arrived in Chicago on Saturday, alumni and members of the Knights of Columbus greeted the team and posed for photos. Notre Dame had become increasingly popular among Chicago’s immigrant community, and local newspapers thoroughly covered the team’s arrival in the city, openly rooting for them over the days leading up the Rose Bowl.

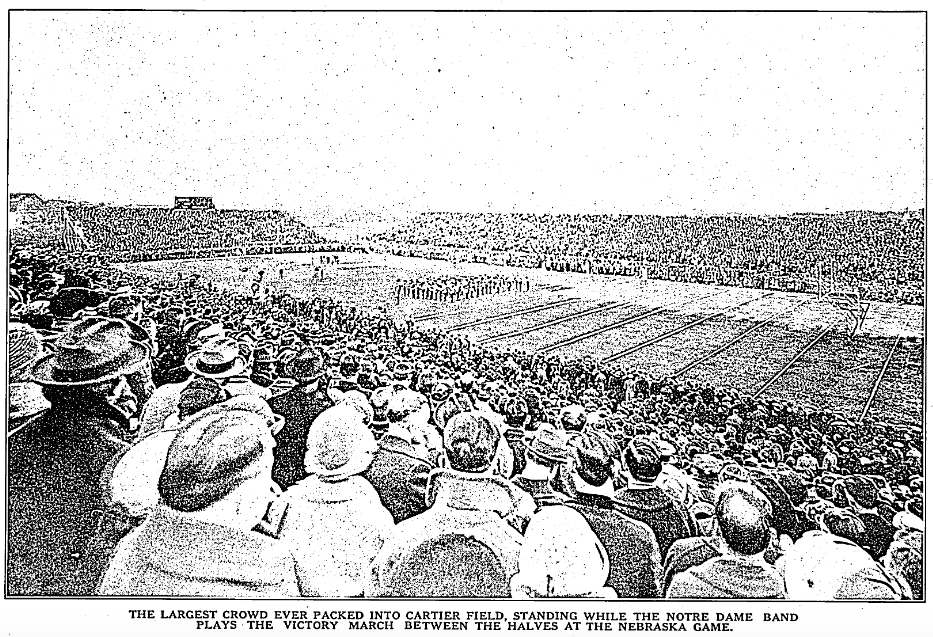

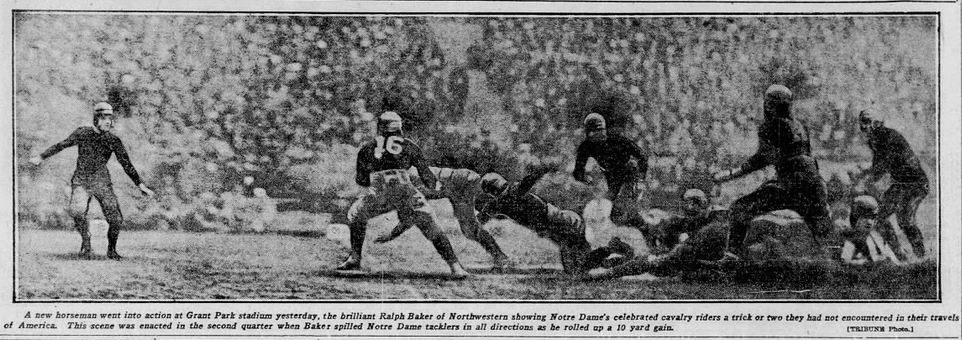

The Chicago Tribune reported that the entire Midwest was “pulling for Knute Rockne’s famous ‘Four Horsemen’ to ride rough shod over the Californians.”[13] The newspaper stated that midwesterners had a vested interest in the game’s outcome “because of the intersectional reputation of Notre Dame, the most widely advertised eleven the country has ever known.”[14] The Tribune reported that while normally telegraph offices would be closed on New Year’s Day, they would “remain open to receive the returns.”[15] The paper also encouraged “everybody with a radio, or those who know somebody with a set” to keep “their ears glued to the headpieces” as Tribune radio station WGN would be airing the game.[16] Pasadena hotel companies even beckoned to Chicago-area residents to follow the team out West for the Rose Bowl through newspaper advertisements.[17] In fact, newspapers all across the country reported on the team’s travels from this first stop. By the time the train left Chicago, the Rose Bowl seats were completely sold out.[18]

The Notre Dame train traveled south, stopping briefly in Memphis, Tennessee, on December 21. Here, the team and entourage were again greeted by alumni and Knights of Columbus members, who had set up a special Mass in the team’s honor. They continued on to New Orleans, where locals pulled out all the stops for “a series of entertainments”over a two-day period.[19] The first day Coach Rockne held an hour-long practice at Loyola University stadium, “consisting chiefly of passing and kicking and the execution of several plays,” and the second day the team spent the afternoon in workouts at Holy Cross College.[20] In the evenings, the team was “elaborately entertained.”[21] According to Burns, “The team was a huge favorite of the large local Catholic population, who turned out in large crowds to cheer and follow the players as they enjoyed the city.”[22] They reportedly enjoyed themselves too much and were “so stuffed with oysters and creole food that they could barely run” at practice.[23] Rockne was not happy and threatened to send players home if they didn’t restrain themselves, maintain their physical fitness, and obey his 10:00 p.m. curfew from this point forward.

The team arrived in Houston, Texas, on December 24 to a now-familiar scene as Notre Dame alumni and the local Catholic community greeted them. Several representatives also arrived from nearby St. Edwards College in Austin, including the college president Father Matthew Schumacher and the athletic director Jack Meager, who was also a former Notre Dame player.[24] Rockne drilled the team hard, despite the rain, and they showed improvement from their lackluster practice in New Orleans.[25] Newspapers reported that Rockne made the team run drills on Christmas day. This was likely a short practice, considering the devout Father O’Hara was supervising the trip, dressing up as Santa Claus that day.[26] The players also attended Mass, a private party, and a Knights of Columbus dinner.[27]

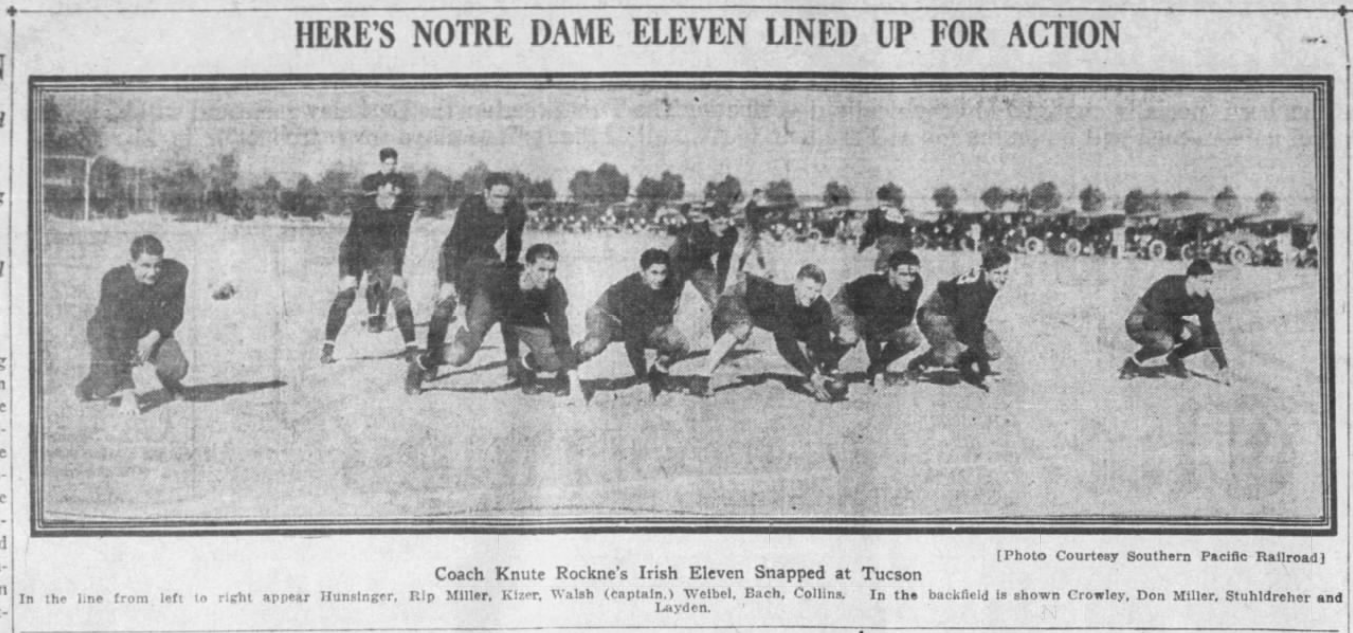

With the Rose Bowl game drawing near, Rockne cancelled the team’s scheduled stop in El Paso, and the train headed straight to Tucson, Arizona, to get down to work. Here the team practiced for four straight days in order to adapt to the warmer climate. Again, Rockne was joined by former players, this time at the University of Arizona stadium. One of these players, Edward Madigan, “scouted Stanford for Rockne” and made the coach aware of a “sideline screen pass that the Stanford coach used two or three times a game.”[28] Rockne devised a play to block this pass and taught the players to recognize its set up. This intelligence would greatly impact the results of the Rose Bowl game.

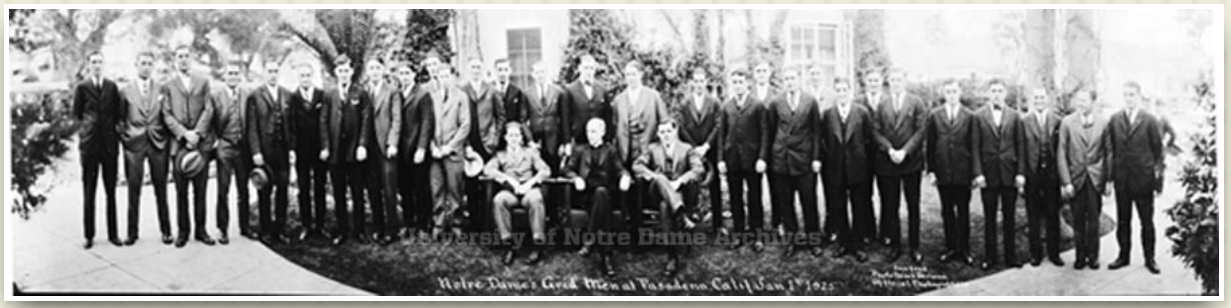

When the team arrived in Los Angeles on December 31, 1924, several thousand supporters met them at the train station. Commenting on the crowd and the success of Notre Dame’s publicity machine, the Notre Dame Alumnus magazine reported:

Despite the early arrival hour, seven o’clock, the station platform was crowded with alumni, Knights of Columbus, members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (who presented a massive silver football to the team) and various motion picture people anxious to see their rivals in publicity.[29]

At least one hundred of the folks gathered on the platform that day were South Bend, Lafayette, and Chicago-based Notre Dame alumni who had arrived on the “Rockne Special,” a Pullman train chartered by the Notre Dame Club of Chicago, to take them from the Windy City to Los Angeles.[30] The train full of super fans garnered its own round of press coverage with wire services reporting on its stops across the country, where these alumni also stopped for daily Mass and were welcomed by local Catholic organizations.[31]

Rockne, worried about the players getting distracted by all the fanfare, had the team driven immediately to their hotel in Pasadena. Even famous heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey couldn’t convince the coach to let him entertain the players first.[32] But the hotel lobby was just as festive as the train platform. Former football player and Chicago Tribune sportswriter Walter Eckersall wrote:

Again at the hotel the squad was accorded another rousing reception for the lobby had been filled all day with curious personas who continually asked to see the warriors who have brought so much glory to Notre Dame.[33]

After checking into the hotel, the team went to the Rose Bowl for practice. Standing in the stadium, the Irish focused on their goal: an undefeated season and a Rose Bowl championship. Coach Rockne worried that they hadn’t gotten in enough practice time during the trip because of inclement weather, but felt optimistic about the plays they studied and ran in Tucson. The players wore “looks of determination on their faces which indicate they realize the burden of responsibility they are carrying.”[34] The Fighting Irish returned to their hotel at 8:30 p.m. without accepting any local offers of entertainment. Rockne notified the hotel staff: “No incoming calls answered.”[35]

Meanwhile, newspapers across the country reported on the practice, debated who would win the following day, and discussed just how evenly matched the two teams were. And the excitement was building. Eckersall wrote:

Every arriving train brings more football fans, and the great majority favor Notre Dame to win. Coaches from all sections of the country are here to get a line on the Rockne style of play and see what all expect to be a great exhibition of open football. [36]

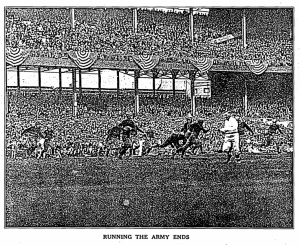

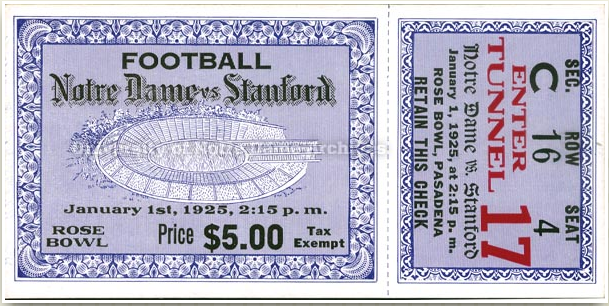

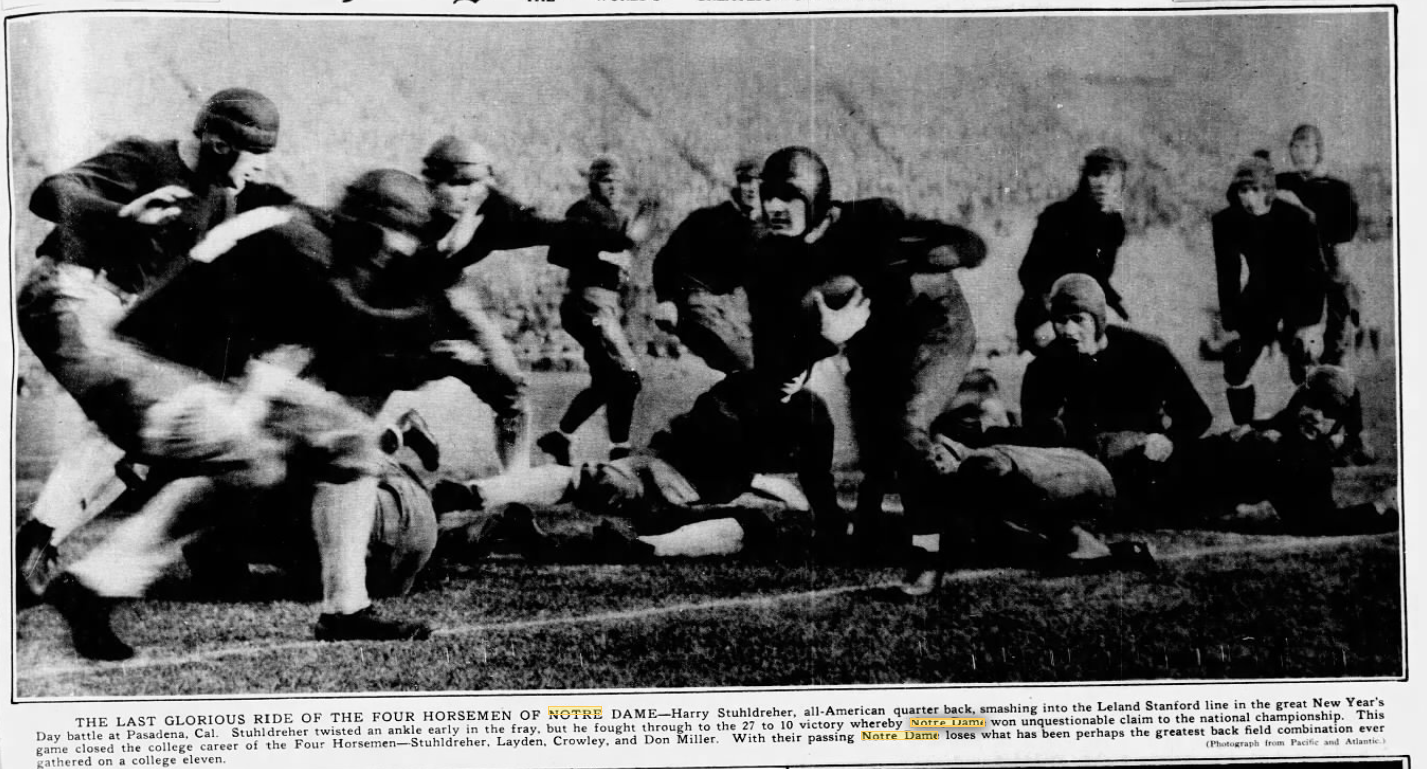

On the warm and sunny New Year’s Day of 1925, the team attended Mass and took Holy Communion before heading to the Rose Bowl. Over 53,000 fans filled the stands and others sat in trees outside the stadium. The game started at 2:15 p.m. (4:15 for those Midwest fans listening to the WGN Chicago broadcast). [37] As usual, Coach Rockne started his second string “shock troops” so as not to tire his first string, especially under the warm California sun. (See Part One on this famous Rockne’s strategy). The shock troops buckled under the pressure of Stanford’s offense and the Cardinals scored first with a field goal. [38]

Stanford continued to outplay Notre Dame in the first quarter, even after Rockne sent his first string players into the fray. According to Burns, “The Four Horsemen could not mount a sustained drive against the huge but agile Stanford line.”[39] When Stanford kicked a bad punt, placing Notre Dame offense on the Stanford thirty-two yard line, the Irish got their first break. Burns continued: “Seven plays later, [full-back Elmer] Layden scored the first Notre Dame touchdown on a three-yard run early in the second quarter.”[40] The score was 6 to 3, Notre Dame. The Cardinals drove the Irish back hard, quickly putting them on the defensive at the Notre Dame six-yard line. Stanford brought out their trusty sideline screen pass, hoping to breeze by the Irish. This was the moment the Horsemen had trained for in Tucson after receiving the scouting report on the play. Coach Rockne explained:

We were primed for that play. Not only had Layden been instructed to intercept it, but we had two men to take out the safety man and the passer in the event that he did intercept the pass.[41]

Not only did Layden intercept the pass, he then ran seventy yards for a touchdown in one of the most exciting moments of the game. Half-back James Crowly kicked the extra point and Notre Dame led at the half 13 to 3. [42]

Although Notre Dame led in points, Stanford was outpassing and outrushing the Irish, while shutting down their offense. The game was “hard fought,” physically exhausting, and Notre Dame looked tired at the half.[43] The Notre Dame Alumnus reported:

The boys were obviously feeling the effects of the long trip, the unusual heat of the day, and the hard, but clean, combat of the game . . . It was doubtful if some of the men, particularly the linemen could finish the game.[44]

Stanford missed two field goals early in the third quarter but kept Notre Dame “confined within their own thirty yard line throughout the period.”[45] About halfway through the quarter, Stanford fumbled, and Irishman Edward Huntsinger grabbed the ball. Coach Rockne had almost sent Huntsinger home days earlier in New Orleans for disobeying curfew to buy postcards in the hotel lobby. The Irish were lucky the coach reconsidered, because Huntsinger ran the recovered ball for another touchdown. Crowley again kicked the extra point, and Notre Dame led 20 to 3 at the end of the third.[46]

The crowd was tense when the fourth quarter began, as the score did not reflect how close the game really was.[47] Stanford intercepted a Notre Dame pass, and “in seven running plays” the Cardinals “moved the ball to a fourth down situation inside the Notre Dame one yard line.”[48] Then,“in the final period Stanford made a beautiful march of 60 yards” to put the ball at the Notre Dame one-yard line on the fourth down.[49] Stanford’s quarterback was stopped only a foot, or mere inches (depending on the report), from crossing the “counting mark” for a touchdown.[50] Layden punted back to Stanford’s 48-yard line, and “again the Cardinal[s] started to march down the field.”[51] With two minutes to go, Stanford again attempted their sideline screen pass. Layden anticipated the move, intercepted the play, and ran 60 or 70 yards (depending on reports) for a touchdown. Crowley came through with the extra point, and Notre Dame beat Stanford 27 to 10.[52] Both teams played exceptional football, and the Rose Bowl game was noted for “aggressive playing” but “remarkably clean” sportsmanship.[53]

The stadium roared with Notre Dame fans “jubilant in victory,” but the Fighting Irish were surprisingly stoic.[54] The Notre Dame Alumnus reported:

As 53,000 spectators jostled their way through the crowded tunnels of the Rose Bowl . . . thirty-three tired young lads dropped their football togs [clothing] on a damp cement floor of the dressing room, for the last time in a long season, silent in their contemplation of a hard-earned victory and buoyed up only by the realization that they had acquitted themselves to the credit and price of Notre Dame and Knute Rockne.[55]

The victorious players were so tired, they couldn’t enjoy the dinner and dance held for them back at their hotel that night. But the Fighting Irish would have to muster up a last bit of energy.[56] For while it had been a long trip to Pasadena and the Rose Bowl title, there was one last but important journey ahead of them: a victory lap across the country and back to South Bend.

On January 2, Hollywood welcomed the victorious Notre Dame team. The Alumnus reported that if there was a famous movie star who did not meet the players that day, it could only have been because the actor was not in town. The Alumnus also noted that “cameras worked overtime” capturing the stars and star players. [57] That night, the Notre Dame Club of Los Angeles hosted a dinner dance which “gave the men their first opportunity to really celebrate.”[58] Father O’Hara was proud to report that at all times the players conducted themselves as honorable gentlemen and good Catholics.[59] After all, a large part of why they were on this trip was to reflect positively on the university. Every team member would have been aware of the expectations.

The next day, January 3, the group arrived in San Francisco. Notre Dame alumni, the Knights of Columbus, and the city’s Irish-American mayor welcomed the Fighting Irish. Perhaps everyone who had been discriminated against in this era of the Klan was feeling a little Irish that day. Herbert Fleishacker, a prominent Jewish San Francisco banker, wrote in a telegram to the alumni group: “WE IRISH MUST STAND TOGETHER.”[60] At the dinner and dance that evening “once again, the players and coaches were charming, properly dressed, and well-behaved.”[61] They attended a special Mass the next morning and spent the day as the guests of some of the city’s most prominent citizens and leaders.[62]

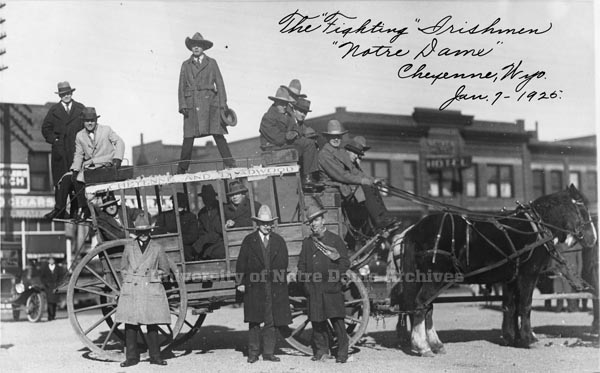

The rest of the trip must have been a whirlwind for the exhausted players. They arrived in Salt Lake City on January 5, where they took historical tours, went to a concert, had dinner, and attended yet another reception. They received a Wild West themed welcome the following day from the local Catholic community of Cheyenne, Wyoming. The Irish were provided with “six-gallon hats, stage coaches, a military band and the key to the frontier town.”[63]

On January 6, a crowd of thousands waited on the platform as the team’s train pulled into Denver. Mothers of Notre Dame students and “a remarkably beautiful group of girls” greeted the players, pinning blue and yellow streamers on their coats.[64] The Denver alumni club reported:

Movie cameras were clicking, press photographers were snapping, and over it all sounds the low rumbling roar of the admiring crowd.[65]

The Denver Alumni Club drove the team through the cheering crowd to the Denver Athletic Club for yet another banquet. Two hundred prominent Denver citizens, including the governor of Colorado, attended the gala, where celebrants sang Notre Dame fight songs. Speeches that night focused on the moral strength of the university and on Catholicism as a powerful force in shaping students into upstanding American citizens. The Denver Alumni Club reported that “no one who attended the dinner can ever forget that Notre Dame builds character, manliness and righteousness along with wonderful football elevens.”[66]

Surprisingly, the next stop on the tour, on January 8, was Lincoln, Nebraska, where the team had been accosted by xenophobic and anti-Catholic insults on the gridiron over the previous two seasons. [See parts one and two]. Only now, they arrived in the city of their conquered rivals as national champions. Lincoln “forgot the defeat of November” at the hands of the Irish and treated them with sportsmanship and respect. The Notre Dame players even attended the inauguration of the new Nebraska governor that evening.[67]

The Notre Dame train pulled into Chicago on January 9. Some players stayed for a few days in the city that had rooted for their victory beside radio sets a week earlier. Others went straight back to South Bend. By January 12, the Fighting Irish had all returned to the university.[68] They were completely exhausted from physical exertion and from continually being on their best behavior. The constant scrutiny of serving as representatives not just of the school, but of Catholics everywhere was a lot of pressure for young students. The Notre Dame Alumnus wrote:

The word ‘banquet’ is an alarm, ‘look pleasant, please’ is an oath and ‘the game’ is an unmentionable now that the men are back on campus — with exams less than two weeks away.[69]

The Fighting Irish had delivered an undefeated season and a national championship to their university. Notre Dame officials, in turn, leveraged the opportunity into a publicity spectacular. Father O’Hara’s plan to use football successes to reform the school’s reputation had worked. Burns noted that “By playing very hard, but always according to the rules, never complaining or making excuses, and winning, Notre Dame players would show the American public what Catholics and Catholic education was all about.”[70] The Fiery Cross continued to blather about Catholic plots and tales of Notre Dame hoodlums, but the country had just witnessed an extended and public display of honorable play, sportsmanship, and model behavior from these young Catholic men. Burns wrote:

For O’Hara and millions of American Catholics throughout the country who believed and felt as he did, and especially for the 300,000 Catholics living in Indiana—11 percent of the population of the state—the performance of the Notre Dame football team in that year gave them all a supreme moment of restored pride and dignity.[71]

The Klan would continue to influence Indiana politics for several years. But other Hoosiers would rise up in opposition like South Bend and Notre Dame. Cities passed anti-mask ordinances to prevent the Klan from marching in their hoods and robes.[72] Prominent citizens founded civic clubs “to fight the Ku Klux Klan.”[73] The Indianapolis Times launched a multi-year “crusade” against the Klan, exposing members’ identities and combating the secret organization’s influence on Indiana politics, and winning a Pulitzer Prize for their efforts. [74] African American voters risked being jailed as “floaters” (someone whose vote was illegally purchased), but came out in record numbers to cast their votes in opposition to Klan-backed candidates.[75] Local Catholic organizations called on politicians to denounce the Klan and include a plank in their official party platforms rejecting “secret political organizations” and supporting “racial and religious liberty.”[76] Indiana attorney Patrick H. O’Donnell led the American Unity League, a powerful Chicago-based Catholic organization that also published the names and addresses of Klan members in its publication Tolerance.[77]

As students of history, we should remember that, in many ways, the Indiana Klan succeeded in their goals. They were able to elect officials sympathetic to the xenophobic demands for strict immigration quotas, which were enforced for decades. But we should also note that some Hoosiers refused to accept intolerance even when wrapped in the flag.

While much of Indiana became Klan territory, the publicity campaign organized by the University of Notre Dame forever crushed the Klan’s plans for infiltrating South Bend and tainting the school’s reputation. South Bend refused to be baited into further physical confrontations with the Klan, school officials refused to accept the insults hurled at them through Klan propaganda, and the Fighting Irish refused to play the Klan’s game. They played football instead. And they played with the honor and dignity imbued through “the spirit of Notre Dame.”[78]

Notes:

For a thorough examination of the opposition to the Klan by African Americans, Jews, Catholics, lawyers, politicians, labor unions, newspapermen and more see: James H. Madison, “The Klan’s Enemies Step Up, Slowly,” Indiana Magazine of History 116, no. 2 (June 2020): 93-120, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/indimagahist.116.2.01.

[1] Jill Weiss Simins, “‘America First’: The Ku Klux Klan Influence on Immigration Policy in the 1920s,” accessed Hoosier State Chronicles Blog.

[2] Indiana Ku Klux Klan, “Information Sheet,” 1922, Indiana Pamphlet Collection, Indiana State Library.

[3] “Tales Need No Adornment,” Fiery Cross, August 22, 1924, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[4] Advertisement, Fiery Cross, August 22, 1924, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.; “High School Boy Writes of Experiences in Notre Dame Riot,” Fiery Cross, July 25, 1924, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[5] Ibid.; “May 17 — November 8,” Fiery Cross, November 21, 1924, 6, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jill Weiss Simins, “Integrity on the Gridiron Part Two: Notre Dame’s 1924 Football Team Battles Klan Propaganda,” accessed Indiana History Blog.

[8] Robert E. Burns, Being Catholic, Being American: The Notre Dame Story, 1842-1934 (University of Notre Dame Press, 1999), 361.

[9] Ibid., 364-65.

[10] Ibid. Burns quoted from Father O’Hara’s Religious Survey for 1924-25.

[11] “Name N.D. Squad,” Chicago Tribune, December 19, 1924, 28, accessed Newspapers.com.

[12] “Stanford – Notre Dame Seats All Sold Out,” Tennessean (Nashville), December 21, 1924, 17, accessed Newspapers.com.

[13] “Midwest Anxious for Notre Dame Victory,” Chicago Tribune, December 31, 1924, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[14-16] Ibid.

[17] Advertisement, Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1924, 21, accessed Newspapers.com.

[18] “Stanford – Notre Dame Seats All Sold Out,” 17.

[19] “Notre Dame Football Team in New Orleans,” News and Observer (Raleigh, NC), December 23, 1924, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus 3, No. 4 (January 1925): 116-17, accessed University of Notre Dame Archives.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Times (Shreveport, LA), December 23, 1924, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.

[22] Burns, 366.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “Saint Coaches to See Micks,” Austin American (Texas), December 24, 1924, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[25] “Notre Dame at Houston,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 25, 1924, 19, accessed Newspapers.com.

[26] “Rockne’s Team Spends Holiday with Practice,” Oakland Tribune, December 25, 1924, 24, accessed Newspapers.com.; “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.

[27] Burns, 366.

[28] Ibid., 367; “Football,” Notre Dame Alumnus 3, No. 4 (January 1925): 106-107, accessed University of Notre Dame Archives.

[29] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 17.

[30] “Rockne Special,” South Bend Tribune, December 19, 1924, 30, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Lafayette’s Off for Coast,” Journal and Courier (Lafayette), December 27, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[31] Ibid.; “Notre Dame to Stop Here,” Kansas City Times, December 18, 1924, 17, accessed Newspapers.com.

[32] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.; Walter Eckersall, “53,000 to See N. Dame Battle Stanford Today,” Chicago Tribune, January 1, 1925, 37.

[33-34] Eckersall, 37.

[35] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.

[36] Eckersall, 37.

[37] “Rose Tournament Throng Sets Record,” Pasadena Evening Post, January 1, 1925, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[38-40] Burns, 368.

[41]“Football,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 106-07.

[42] Burns, 368.

[43-44] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.

[45-46] Burns, 368.

[47] “Iowan Stars as Notre Dame Beats Stanford Team,” Des Moines Register, January 2, 1925, 7, accessed Newspapers.com.

[48] Burns, 368.

[49] Ibid.; “U.S. Title to Notre Dame,” Chicago Tribune, January 2, 1925, 1, 19, accessed Newspapers.com.

[50] Ibid.

[51] “U.S. Title to Notre Dame,” 19.

[52] Burns, 368.

[53] “U.S. Title to Notre Dame,” 19.

[54-55] “Football,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 106.

[56-58] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 116-17.

[59] Burns, 369-70.

[60] Murray Sperber, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993, reprint, 2003), 171.

[61] Burns, 370.

[62-64] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.

[65] “Local Alumni Clubs,” Notre Dame Alumnus 3, No. 4 (January 1925): 115, accessed University of Notre Dame Archives.

[66] Ibid.

[67] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.

[68] Burns, 372.

[69] “To Pasadena and Return,” Notre Dame Alumnus, 117.

[70] Burns, 349.

[71] Ibid.

[72] “Michigan City Passes Anti-Mask Resolution,” Star Press (Muncie, IN), September 8, 1923, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

[73] “Political Club to Fight Klan in Lake County,” Times (Munster), April 10, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[74] Indiana Historical Bureau, “Indianapolis Times,” 2013, accessed State Historical Marker Text and Notes.

[75] “Many Factions Clash,” Indianapolis Star, May 6, 1925, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

[76] “Request Parties to Oppose Klan,” Call-Leader (Elwood, IN), January 29, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[77] “Former Local Man to Fight Ku Klux Klan,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, September 16, 1922, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

[78] Jim Langford and Jeremy Langford, The Spirit of Notre Dame (New York: Crossroad Publishing Co., 2005), passim.