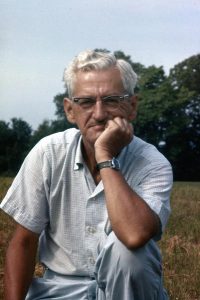

Glenn A. Black (1900-1964), native of Indianapolis, became one of Indiana’s leading archaeologists in the midst of the Great Depression. He was essentially self-taught, having only a small amount of formal training with Henry C. Shetrone of the Ohio Historical Society (now Ohio History Connection). Black’s work redefined archaeological field methodology, and brought systematic excavations and innovative technology to the field.

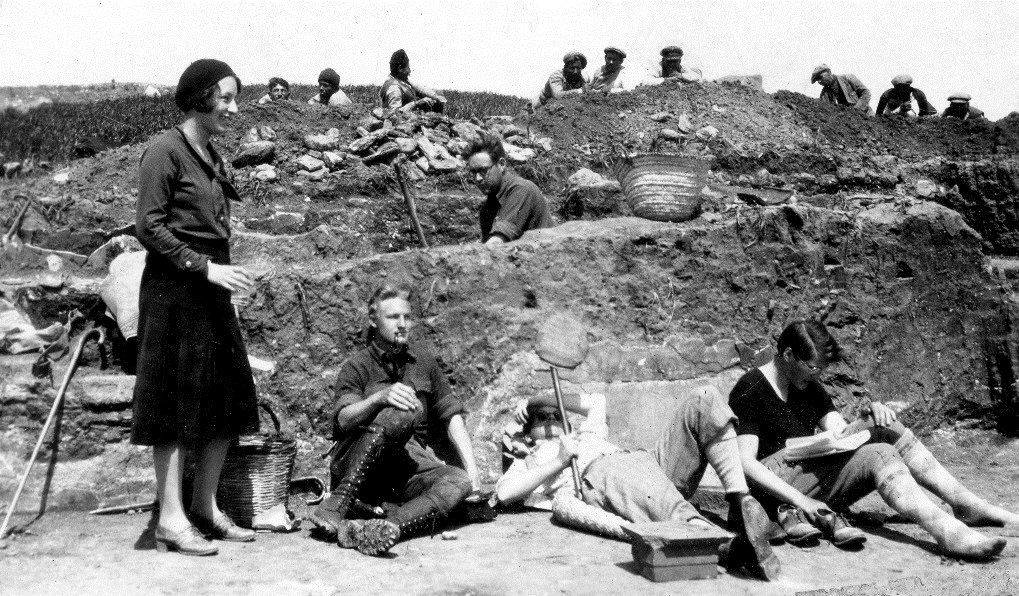

Black began his archaeological career by serving as a guide for Warren K. Moorehead and Eli Lilly Jr. in May 1931. Impressed with Black’s knowledge, they encouraged him to become an archaeologist. Lilly funded Black’s work with his own money initially, and later arranged for him to be paid through the Indiana Historical Society’s archaeological department. Lilly also helped Black with his formal training, sending him to Columbus, Ohio from October 1931 to May 1932 to train with Henry C. Shetrone. During this training, Black married Ida May Hazzard, who joined in his digs. He became especially close with Eli Lilly, forming a bond that would last for the rest of his lifetime.

Black and Lilly worked together on many projects, but one of their more controversial projects concerned the Walam Olum, a historically disputed story of the creation of the Delaware tribe. Lilly and Black “had a hunch that the Walam Olum may possibly have in it the key that will open the riddle of the Mound Builders.” In short, they were “trying to connect the prehistoric people who had built the great mounds of the Ohio Valley with the historic Delaware tribe.”

The Walam Olum story was first told by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1836. Rafinesque announced that he had acquired some “tablets” that depicted the “ancient record of the peopling of North America that had been written by the early Lenape (Delaware) Indians and passed down in the tribe for generations.” He had translated the tablets into English, and called it the “Walam Olum” or “painted record” in Lenape. In the years following his death, notable historians, linguists, and ethnologists believed that it “contained crucial evidence for prehistoric Amerindian migrations and the identity of the mysterious Midwestern Mound Builders.” Lilly and Black believed in this theory, and began analyzing the Walam Olum with a team of experts. Their report, published in 1954, claimed “all confidence in the historical value of the Walam Olum.” More recently, historians believe that the Walam Olum was a hoax created by Rafinesque to prove his belief that the Indians came to North America from the Old World.

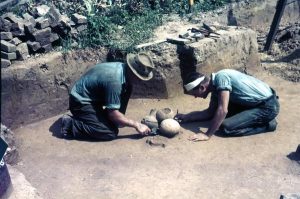

In 1934, Black was asked by the Indiana Historical Society to excavate the Nowlin Mound in Dearborn County. Ida joined him on this dig, as she was “deeply interested in delving into the archaeological as her talented husband.” It was here that his intensely methodical process of excavating is evident. In his report on the mound, he wrote, “If the results of any excavation are to provide an unimpeachable historical record of a prehistoric work, too much stress cannot be placed upon methodical technique and exactness of detail, no matter how trivial the feature may be.” He felt very strongly about following a methodical excavation system, believing that it would lead to improved results and a better historical record.

“if the description of the methods used in staking and surveying the mound seems unnecessarily extensive, it should be remembered that a mound once dug is a mound destroyed; if the story it has to tell be lost on the initial attempt it is lost forever.”

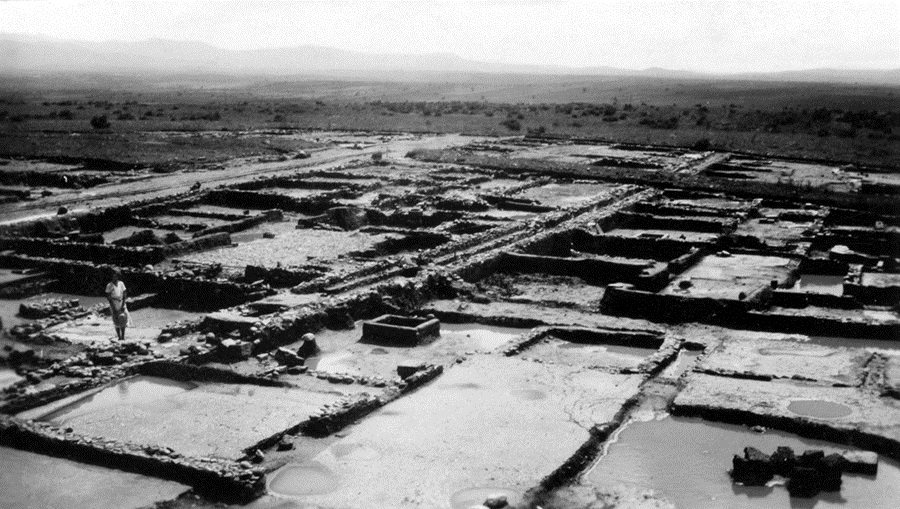

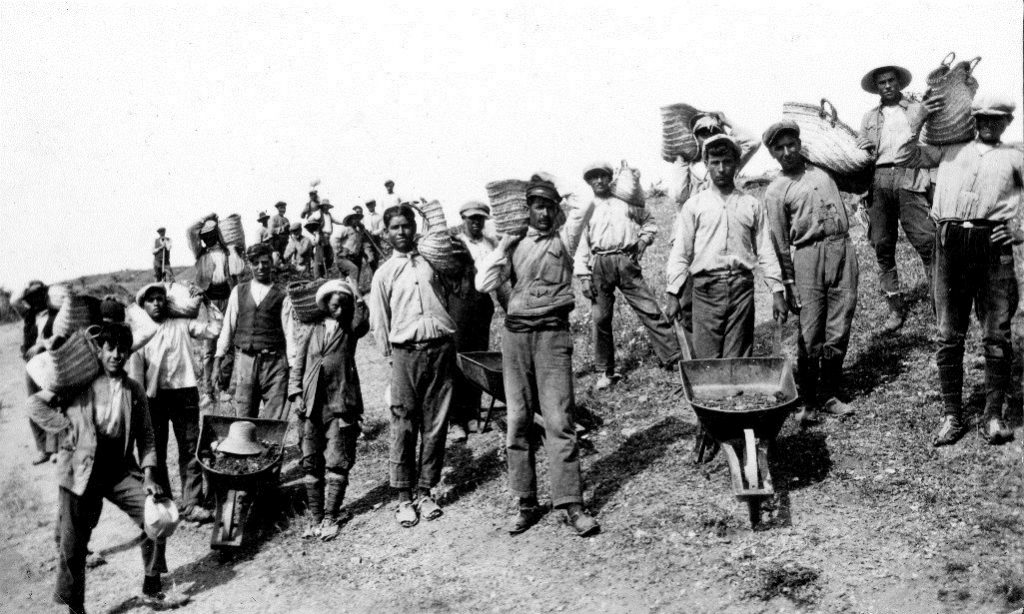

In 1938, the Indiana Historical Society purchased Angel Mounds with the help of Eli Lilly. Lilly contemplated purchasing the site since 1931, but when the site was in danger of being incorporated by the City of Evansville in 1938, he acted. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) conducted excavations from 1939-1942, and IU’s field program excavated beginning in 1945 (work temporarily ceased during WWII). Black held his students in the field program to very high standards.

In a letter to his students, Black wrote:

You will be living for ten weeks in very close association with your fellow students and you will be expected to get along with one another in an agreeable manner. This is one of the very few field camps which accepts mixed groups. As such we are under constant surveyance by those in this neighborhood and at the University who do not believe in girls attending field schools. I do not subscribe to this thesis but that I may be proved right, and my critics wrong, I am dependent on you. I expect the girls be ladies and the boys gentlemen and all of you to be discreet and orderly at all times. It is requested that you do not wear shorts on the dig—they are neither practical or appropriate.

In the spring of 1939, Black moved to a house on the Angel Mounds site and began supervising the excavations. He and Lilly used the WPA to supply workers to excavate from 1939-1942. Two-hundred and seventy-seven men and 120,000 square feet later, Black and the WPA recovered and processed more than 2.3 million archaeological items. From 1945-1962, students worked at the site in the summer to extend the work of the WPA. The years 1945-1947 were used as “trial runs” of the program, and the first official class began in June 1948. Stemming from this work, an organization was created in 1948 called The Trowel and Brush Society. This society limited membership to students enrolled in the Angel Mounds Field School, but created an honorary category for those who were unable to join formally, but had “contributed to American Archaeology in general and Indiana Archaeology in particular.” The purpose of this society was “to promote good techniques in archaeological research; to maintain contact between students who attend Indiana University’s Archaeological Field School.”

Through his excavations, Black concluded that Angel Mounds existed long before the discovery of America, and was most likely still a “lively community during and after the period of DeSoto,” and does not have evidence to suggest that the site was visited by white men. He believed that Angel Mounds was the site of the “farthest north existence of an agricultural Indian folk who were a part of the long settled tribes of southern and southeastern United States.” An encyclopedia entry about Angel Mounds estimates that the community flourished between AD 1050 and 1450 and that the settlement was geographically and culturally central during Angel Phase, the portion of time from AD 1050-1350 characterized by the Mississippian culture’s use of ceramic, of which there is plenty at Angel Mounds.

Even after concluding this from his excavation, Black said in 1947 that “There’s plenty here to keep me busy the rest of my life.” In 1958, Black became interested in locational devices to detect features of the mounds. He saw that the use of a proton magnetometer was announced in Britain by the Oxford University Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art. Reportedly the device was successful in locating features at Roman sites. Black began looking for one to use at Angel Mounds. In September 1960, the Indiana Historical Society purchased a magnetometer instrument for use at Angel Mounds. The purpose of this project was “to evaluate the application of the proton magnetometer to the problem of locating subsurface features on archaeological sites in this part of the world, and to extend the work begun by the Oxford Group.”

In 1946, the site was transferred to the State of Indiana. After Black’s death in 1964, the Indiana Historical Society and the Indiana Department of Natural Resources transferred the site to Indiana University in an attempt at “making Indiana university the archaeological center of the state” and to use the site as a research and teaching facility. In 1964, Angel Mounds was registered as a national historic landmark. Today, the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites Corporation manages the site.

Black’s other notable achievements included: vice-president and president of the Society for American Archaeology; Archaeology Divisional Chairman for the Indiana Academy of Science; member of the National Research Council; awarded an honorary doctorate by Wabash College.

Glenn Black died September 2, 1964 in Evansville, following a heart attack. Lilly used the Lilly Endowment to create the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology after his friend’s death, dedicating it on April 21, 1971. When Black died, he was almost done with his report on the Angel Site. Former student James A. Kellar and editor Gayle Thornbrough finished it. The Indiana Historical Society published it in 1967 in two volumes, titling it Angel Site: An Archaeological, Historical, and Ethnological Study. The sections that Black completed before his death include the “historical background, chronological account of its excavation, ethnological relationships, and the ecology of the area.” After his death, Kellar wrote the section that dealt with material that had been recovered from the site. Indeed, plenty at Angel Mounds to keep him busy for the rest of his life.

Learn more about Lilly and Black’s investigation into the Walam Olum, see Walam Olum, or Red Score: The Migration Legend of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians: A New Translation, Interpreted by Linguistic, Historical, Archaeological, Ethnological, and Physical Anthropological Studies.

Check back for information about IHB’s forthcoming marker dedication ceremony honoring Glenn A. Black.