On Valentine’s Day, we thought it would be a great time to share a different side of Indiana culture during the tumultuous years of World War I, in the form of valentine cartoons. John T. McCutcheon was one of Indiana’s most celebrated cartoonists from the era, and his “wartime valentines” help us understand how the home front viewed this integral time in world history.

John T. McCutcheon was a Pulitzer-Prize winning cartoonist for the Chicago Tribune, where he worked for 43 years. Born in South Raub, Tippecanoe County, Indiana on May 6, 1870, McCutcheon grew up “in the rural areas surrounding Lafayette.” He attended Purdue University where he was “a founding member of the University’s first fraternity, Sigma Chi” and the “co-editor of the University’s first yearbook, the Debris.” After graduating college in 1889, he worked as a cartoonist for the Chicago Morning News and Record-Herald until he moved to the Tribune in 1903. His artistic style mirrored his experiences growing up the Midwest; he developed a character called “A Boy in Springtime” who would appear in front-page pieces having small-town fun with friends and his dog (the dog first appeared in a William McKinley presidential campaign cartoon, and became much beloved by readers). As R. C. Harvey of the Comics Journal noted, McCutcheon’s cartoons were “the first to throw the slow ball in cartooning, to draw the human interest picture that was not produced to change votes or to amend morals but solely to amuse or to sympathize.”

Paralleling his more personable cartoons, McCutcheon partnered with another Hoosier author, George Ade, to create a series of valentines for charity during World War I. The idea originated from the Indianapolis Branch of the American Fund for French Wounded and its contributors were a who’s who of Indiana arts, including Ade and McCutcheon as well as Meredith Nicholson, Kin Hubbard, and William Herschell. As reported in the South Bend News-Times on January 28, 1918, “Prominent Indiana artists and authors this year have been making comic valentines . . . and are guaranteed by those who have seen them to send grins and cheer to soldiers at home and abroad.” The article also outlined the American Fund for French Wounded, noting that “the proceeds will go for furthering the work in France among wounded soldiers and destitute families, which is the committee looking after the funds is carrying on.” Ads even ran in the Indianapolis News to promote the Valentines, published by Charles Mayer & Company, once they were available.

Four of McCutcheon and Ade’s valentines are publicly available through Indiana Memory/Digital Indy and the Digital Public Library of America.

The first valentine in the digital collection, entitled “From Her Mother”, shows a concerned mother writing to a “Mr. Soldier Man” while a variant of McCutcheon’s iconic dog looks on in the background. The photos on and above the desk in the cartoon are important to context, as the photos of the mother’s daughter and her soldier beau face each other longingly, while a portrait of the mother sternly oversees over both of the photos. In the cartoon, the mother’s letter reads:

Mr. Soldier Man.

Dear Sir:

I can not send what my daughter wrote,

It might set fire to the darned old boat.

Yours truly,

– The Night Watch.

The mother’s face shows a concern not only for her daughter’s overly passionate words. McCutcheon’s style of strong lines and warm, humane features also comes through in this valentine.

Another great valentine in the collection entitled, “Her Choice This Year”, ties the romantic love normally associated with Valentine’s Day with love of country. Ade’s poem reads:

Columbia wants you to know,

That you’re her particular beau.

She’s likewise “particular.” So

That’s why you’ve been picked as her beau.

The young woman, aptly named Columbia, holds the hand of her uniformed soldier as he looks at her lovingly. She’s also dressed in a shirt and skirt of the red, white, and blue with a pair of roman sandals. And of course, McCutcheon’s iconic dog looks up at them in the foreground. This valentine exhibits the strong patriotic fervor during the period, but in a charming, homespun way.

The next valentine captures a woman’s longing for her partner who is off at war. Named “Some One Has Not Forgotten,” it depicts a young woman knitting in a chair while thinking of her partner trekking across Europe in a snowstorm. Here’s Ade’s text with the valentine:

My heart to-day

Is far away

Across the rolling brine.

So while I sit

And knit and knit

You’re still my valentine.

This depiction of men and women evokes a more traditional assumption of gender during the period than say “Columbia” and her beau above. The woman’s thoughts of her partner, floating above her head and colorless, attempt to convey the arduous and grim task of war. In contrast, McCutcheon’s drawing of the young woman is clear and with beautiful coloring. Ade and McCutcheon’s valentine cleverly renders the feelings of many young women while their partners were at war.

The final valentine in the digital collection is called, “To You Somewhere,” and it depicts one of Valentine’s Day’s most enduring symbols, Cupid. In this version, a nude Cupid braves the cold weather to deliver a valentine to a soldier in the snow. The message reads:

I don’t know just where you are to-day,

I don’t know how many miles away;

Whether you’re out where the bullets fly,

Or safe and sounds at the good old “Y.” [Y.M.C.A]

I have no message from o’er the sea

To let me know that you think of me,

But I’ll make an oath and my name I’ll sign,

That you are my only Valentine.

The soldier’s delight at receiving the message from a saluting cupid is evident. He even has his gun down and his hands up, perhaps in surprise that the symbol of love is in a war zone, or perhaps the soldier is in the act of accepting the valentine from Cupid. Of the four digitized valentines, this is the only one without a female main subject, despite the text being from the soldier’s love. It shows the perspective of the soldier receiving a valentine, rather than a woman creating or imagining one.

During a time of immense destruction, political revolutions, and domestic instability, Ade and McCutcheon’s valentines provide us with a more homespun, sometimes humorous, quaint and patriotic view of the home front during World War I.

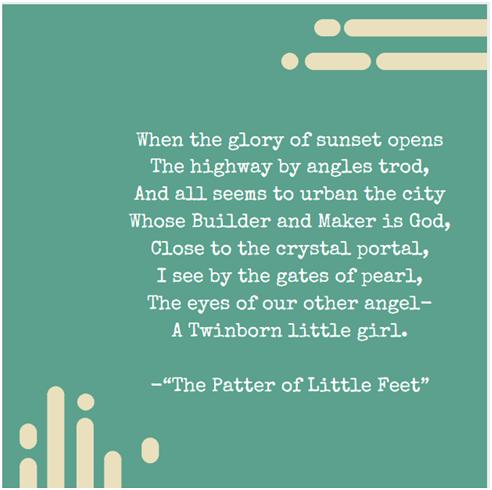

The poem goes on to describe the mother’s longing that she will someday reach heaven and hear the patter of her daughter’s feet on heaven’s floor.

The poem goes on to describe the mother’s longing that she will someday reach heaven and hear the patter of her daughter’s feet on heaven’s floor.

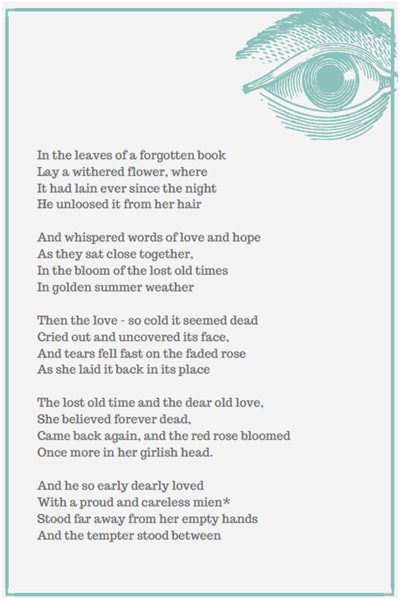

Interestingly, this poem does not seem to have raised any speculation regarding Lew’s faithfulness to Susan.

Interestingly, this poem does not seem to have raised any speculation regarding Lew’s faithfulness to Susan.