On Wednesday September 30, 1936, The Greencastle Daily Banner heralded the announcement that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt officially started his reelection campaign the day before. On the same page came news of another federal concern, the allocation of over $800,000 to projects of the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). The news was an important victory for Indiana’s rural electrification projects, which had received a boost in the previous year.

Indiana has a long history with electrical power. In March 1880, the Wabash County Courthouse installed electrically powered lamps, reportedly becoming the First Electrically Lighted City. By the late 1880s, companies were providing electrical services to Indianapolis proper. In 1887, Purdue University hired its first Head of the School of Applied Electricity, and the next year formally opened its School of Electrical Engineering. These engineers continued pursuing the development of better systems for electrical use during the era of Edison, Westinghouse, and Tesla.

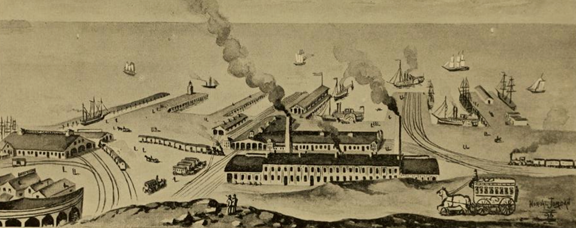

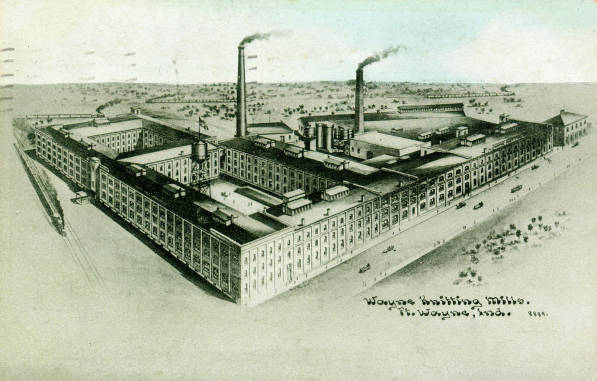

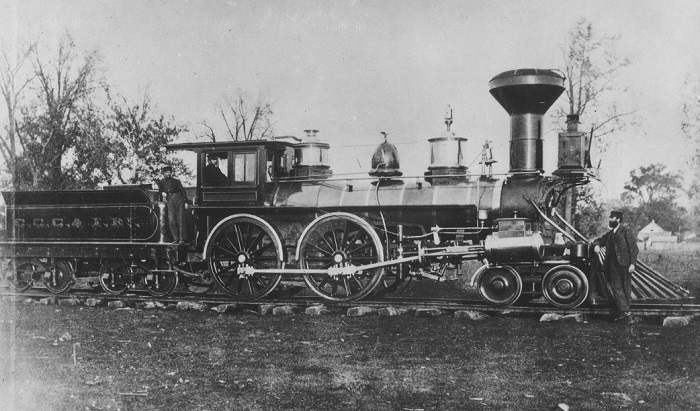

According to Hoosiers and the American Story (2014), in 1900 the creation of a massive electrically-powered interurban train system carried Hoosiers throughout the state, linking towns to Indianapolis and other areas with close to 400 trains running on a daily basis. In 1912, one of Edison’s former employees, Samuel Insull created the Interstate Public Service Company by combining the resources of several predecessors into a single Indianapolis-based company (the company would eventually come to be known as Duke Energy). By this time, the interurban system began to recede in light of the introduction of automobiles.

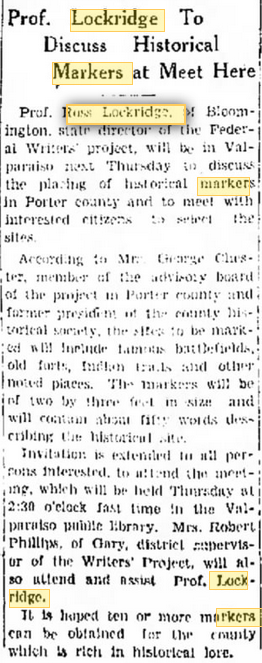

Around the same period, Purdue began doing outreach to rural communities through the Co-Operative Extension Service (Extension) first through state funding, and then as a part of the Smith-Lever Act of 1914. These programs were facilitated by County Extension Agents who served as journeymen experts, arranging workshops and showcases to spread agricultural, and eventually home-economics, lessons from techniques developed at Purdue. It took until the early 1920s, though, before research literature began to tackle the question of rural electrification.

This is not to imply that efforts were not consistently underway to encourage electrical use. On the contrary, the Indiana & Michigan Electric Company hosted an Electrical Prosperity Week in November 1915; their advertisement on page four of the November 30, South Bend News-Times announced “You can spend a couple of hours most enjoyably—and very profitably—at the Electric Show, and it will cost you nothing.” Beyond the showcase, the next page announced a $10.00 prize for the best 200-word essay on the utility of electricity. The Swartz Electric Company ran a promotional train with examples of the modern conveniences provided by electricity, “under the auspices of Purdue University, with equipment suggested for modern farm homes.”

Yet, with all this promotion, the vast distances and relatively low potential for return on investment limited most electrification to cities and larger towns. As late as 1925, one researcher noted this problem in “Electrifying the Farm and Home,” stating “in order to make a profit they [power companies] have charged the farmers so high a rate that it has kept them from using the service.” Indiana had begun to reach out to their rural communities, just not with power, yet.

Historian Audra J. Wolfe’s “‘How Not to Electrocute the Farmer:’ Assessing Attitudes Towards Electrification on American Farms, 1920–1940,” tracks the process and problems of making this rollout happen. Several early research reports document the hazards of incorporating electrical equipment, particularly generators and batteries, into farming homes, as Wolfe notes, “many women avoided them [substations and gas-powered electric appliances] as they had a tendency to explode.”

On June 5, 1925, The Muncie Post-Democrat carried news of an announcement by researchers at Purdue that they would be undertaking the experimental electrification of two farms, one in northern part of the state run by the Calumet Gas & Electric Company and one in the southern part of the state run by the Interstate Public Service Company. These experiments would include checking on the efficacy of implementing electrical components into crop, animal, and household farm operations, as well as to begin developing the resources necessary for statewide electrification. Starting in January 1927, the Daily Banner announced that Purdue would be sending out a “traveling school on wheels” via the interurban system to “demonstrate the employment of electricity” and included experts in agriculture as well as presentations by a home economist, “to attract the feminine eye.” In 1933, Extension published and distributed Leaflet No. 187, “Care and Operation of Electric Household Equipment.” In it, the author outlines some of the variety of electrical appliances and tools which were becoming available to rural homemakers, and notes that “More than 30,000 Indiana farms are now using electricity . . .” Certainly, the university believed that rural electrification was a matter of probability and time, not a question of possibility.

More assistance was needed though for rural electrification to become a reality in the homes of Indiana farmers. Researchers continued to push and though it took some time, by the middle of the next decade, Hoosier lawmakers decided that the time had come to intervene. In 1935, Indiana became part of a growing number of states to enact legislation aimed at developing electrification capacity. According to statistics from the Indiana Law Journal, when Indiana passed its act allowing for the incorporation of rural electric membership corporations who could seek federal financing, almost 150,000 farm homes lacked the ability to access electric power.

On July 22, 1935, the Boone County Rural Electric Membership Corporation (REMC) became one of the first funded federal electric projects in the country, and the first in the state. On August 6, the Daily Banner announced the creation of the Indiana Statewide Rural Electric Membership Corporation. In January 1936, Boone County REMC ran its first 5 miles of power lines to the Clark Woody farm.

This legislation was given an important boost when in 1936, President Roosevelt established the REA and began allowing for distribution of public support dollars. In Indiana, the process of establishing REMCs and encouraging electrification fell to the Extension Service. Over the next four years, Extension Agents helped to form numerous REMCs across the state. In 1937, Extension began distributing Bulletin 215, “Selection, Operation, and Care of Electric Household Equipment,” an update to their 1933 publication which boasted “More than 35,000 Indiana farms are now using electricity . . .” This progress was not always consistent, but it was certainly effective. According to Dwight W. Hoover, between 1930 and 1940 electrified Hoosier farms went from 1-in-10 to 1-in-3. According to Teresa Baer, “By 1965, nearly all Hoosier farms had electricity.” Thus, it took nearly eight decades of sustained effort for most rural Hoosiers to gain access to one of the utilities that we so often take for granted today.

Suggested Reading:

D.L. Marlett and W.M. Strickler, “Rural Electrification Authorities and Electric Cooperatives: State Legislation Analyzed,” Journal of Land and Public Utility Economics, 12, no. 3 (Aug. 1936), pages 287–301).

Barbara Steinson, “Rural Life in Indiana, 1800–1950,” Indiana Magazine of History, XC (1964), pages 203–250.

Audra J. Wolfe, “ ‘How Not to Electrocute the Farmer:’ Assessing Attitudes Towards Electrification on American Farms, 1920–1940,” Agricultural History, 74, no. 2 (Spring 2000), pages 515–529.

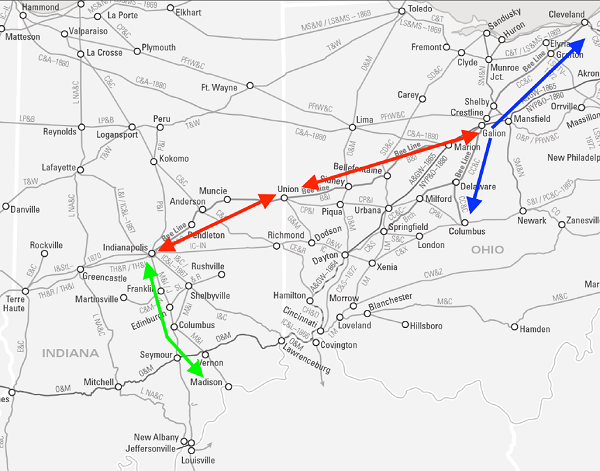

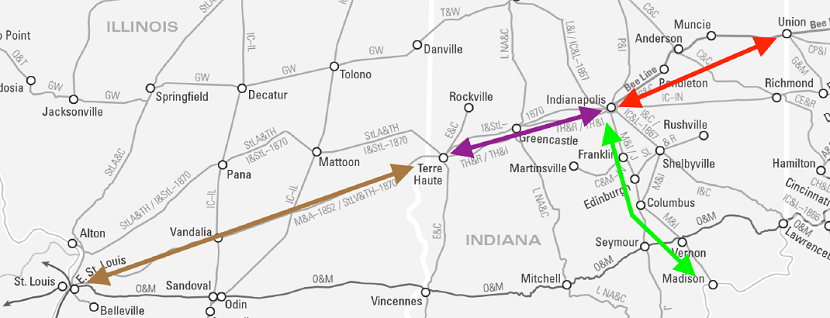

![Midwest Railroads Map, circa 1860, showing the Madison and Indianapolis [M&I], Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], and component roads of the Bee Line: Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati [CC&C]; Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I]; Indianapolis and Bellefontaine](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Midwest-Railroads-Map-c1860.png)

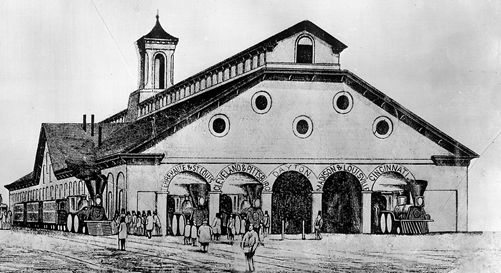

![Railroads west from Indiana, including the Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], Ohio and Mississippi [O&M], Mississippi and Atlantic [M&A], and St. Louis, Alton and Terre Haute [StLA&TH]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Railroads-West.png)

![image of The Madison and Indianapolis Railroad [M&I] and involved roads: the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad [P&I], extending north from Indianapolis, and the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], extending west to St. Louis. Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MI.png)